Abstract

-

Purpose

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) patients have a higher risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) incidence and mortality than those without MetS. The effects of non-pharmacological exposures may help improve the management of CVD. This study aimed to assess the long-term effects of non-pharmacological exposures on CVD in MetS patients through a meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies.

-

Methods

Searches were conducted in seven databases (PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane, RISS, NDSL, and KoreaMed) between August 7, 2024 and December 1, 2024. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. The meta-analysis was conducted using the RevMan 5.4 program and RStudio 2022.12.0. A total of nine studies were included in the systematic review, with eight studies analyzed in the meta-analysis (PROSPERO CRD42024584658).

-

Results

A total of nine studies were included in the systematic review, of which eight were eligible for meta-analysis to evaluate the effects of non-pharmacological exposures. Eight studies were included for meta-analysis to investigate the effect of non-pharmacological exposures. The quality of individual studies was rated “good” for eight studies and “poor” for one. Non-pharmacological exposures in MetS patients were effective in reducing CVD-related mortality (relative risk [RR]=0.81, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73–0.91) and all-cause mortality (RR=0.80, 95% CI, 0.75–0.85).

-

Conclusion

Interventions and education on non-pharmacological exposures in MetS patients are associated with reduced CVD. As evidence continues to emerge, future studies should explore the long-term effects of diet, smoking, and sleep by assessing their individual impacts on CVD outcomes in individuals with MetS.

-

Key Words: Cardiovascular diseases; Cohort studies; Follow-up studies; Meta-analysis; Metabolic syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of metabolic risk factors—including abdominal obesity, hypertension, impaired fasting glucose, hypertriglyceridemia, and reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [

1]. The global prevalence of MetS ranges from 12.5% to 31.4% [

2], with recent Korean data reporting a national prevalence of 24.9% and a marked increase among older adults [

3]. Individuals with MetS are at elevated risk for both the incidence and mortality of cardiovascular disease (CVD), including coronary artery disease, stroke, and heart failure, as well as all-cause mortality [

4]. Beyond its clinical burden, MetS adversely affects quality of life [

5] and contributes to rising healthcare costs [

6]. Lifestyle factors such as smoking and physical inactivity further exacerbate these risks. For example, smokers with MetS are nearly twice as likely to develop CVD [

7], and physically inactive individuals have up to 2.75 times higher risk of CVD-related mortality than active individuals without MetS [

4].

Pharmacological therapy has demonstrated meaningful efficacy in the management of MetS, with weight-reduction effects of up to 15%, while lifestyle modification typically results in a 5% to 10% reduction in body weight [

8]. Furthermore, evidence indicates that combining lifestyle modification with pharmacological therapy leads to greater improvements in systolic and diastolic blood pressure and total cholesterol levels than pharmacotherapy alone [

9]. Prior studies have also shown that exercise and the Mediterranean diet produce significant improvements in blood pressure, lipid profiles, waist circumference, and glycemic control in individuals with MetS [

10,

11]. Additionally, sleep disturbances and shorter smoking cessation durations have been associated with increased MetS and CVD risk [

12,

13].

Despite these promising findings, most existing studies have focused on short-term outcomes, and evidence regarding the long-term effects of non-pharmacological exposures on CVD incidence, CVD-related mortality, and all-cause mortality in MetS populations remains limited. Because MetS and CVD are chronic conditions that develop over decades, long-duration studies are essential to capture the sustained effect of lifestyle exposures on clinical outcomes [

4]. While randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide strong causal evidence for short-term changes in risk factors (e.g., such as blood pressure) high-quality observational cohort studies are indispensable for evaluating long-term clinical outcomes, including mortality, in real-world settings [

14].

Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis synthesizes current evidence from cohort and case-control studies to assess the long-term impact of non-pharmacological exposures, including physical activity, diet, sleep, and smoking, on CVD incidence, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality in individuals with MetS. The findings underscore the importance of evidence-based nursing interventions and contribute to the development of effective, patient-centered strategies for chronic disease prevention and health promotion.

METHODS

1. Study Design

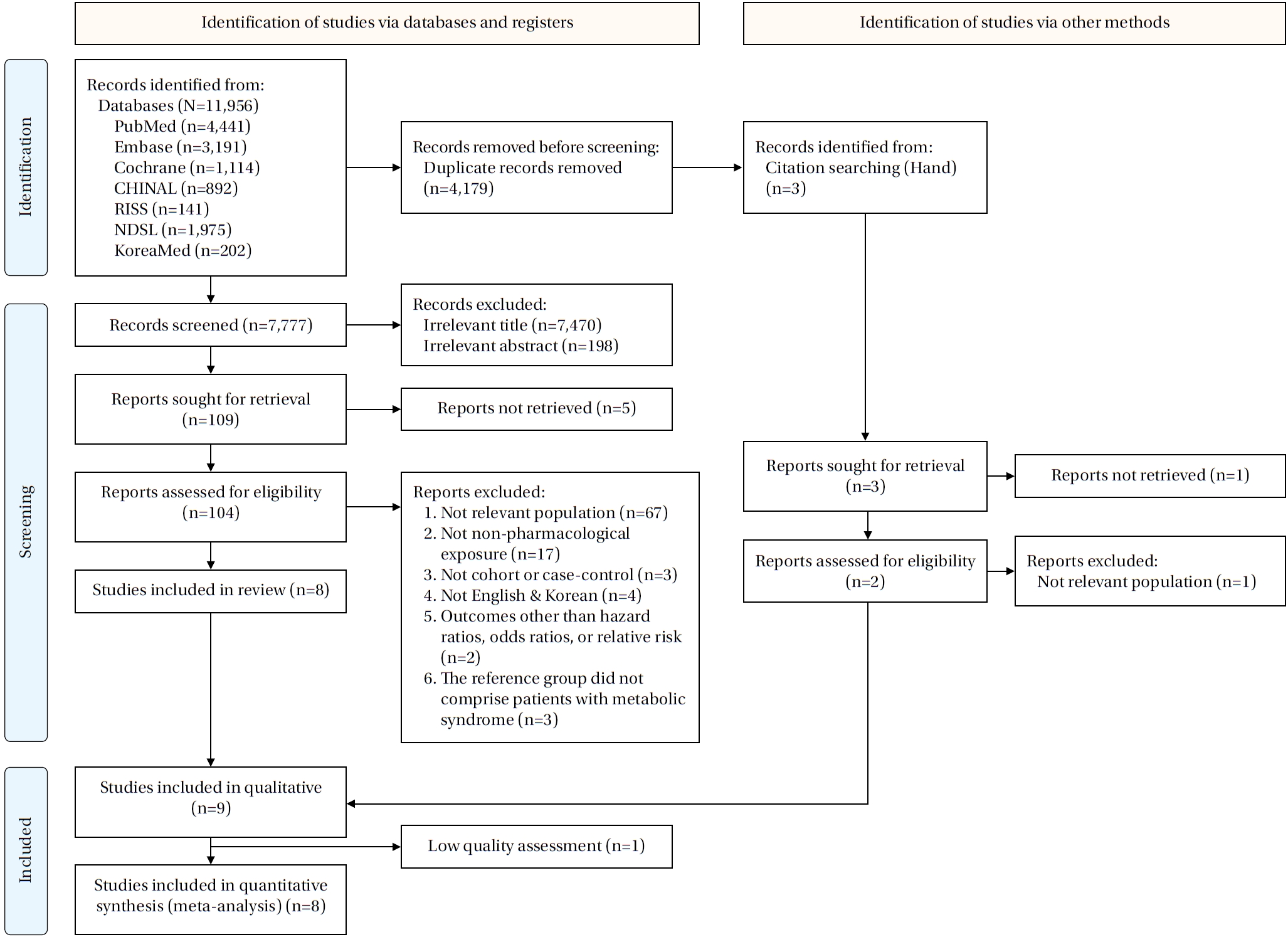

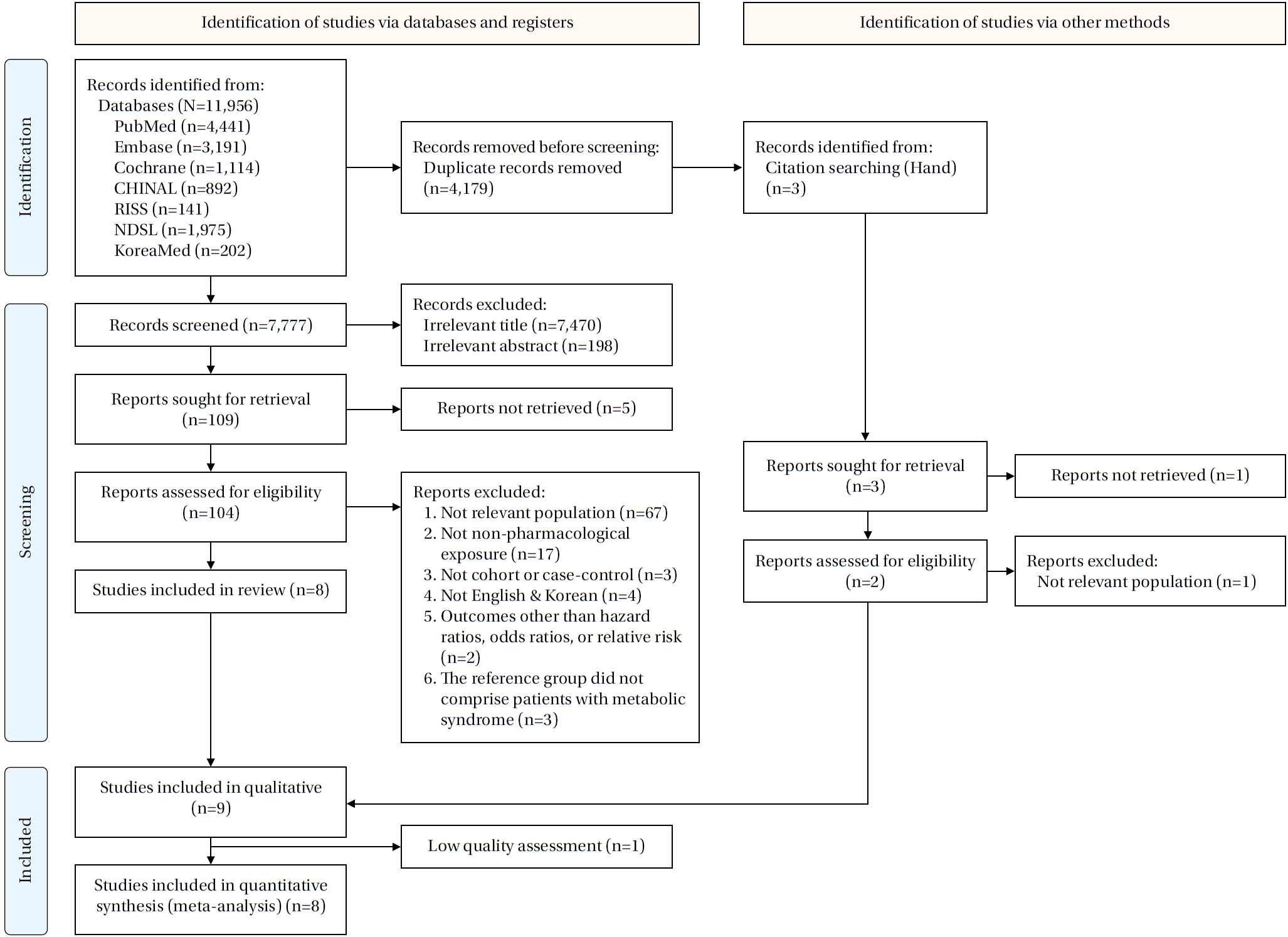

This study is a systematic review and meta-analysis conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) [

15] 2020 statement [

16]. The review protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42024584658).

The primary research question for this systematic review and meta-analysis was: “What are the effects of non-pharmacological exposures on CVD incidence, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality in patients with MetS?” All peer-reviewed studies were eligible, and inclusion criteria were defined using the PECOS framework (Population, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome, Study Design): (1) P: patients with MetS diagnosed according to established criteria, including the National Cholesterol Education Program–Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP-ATP III), American Heart Association (AHA), the harmonized MetS definition, the Diabetes Society of the Chinese Medical Association, or the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) guidelines; (2) E: non-pharmacological exposures such as physical activity, diet, smoking, and sleep. Because this review aimed to comprehensively examine lifestyle-related exposures, we did not restrict the scope to predefined categories; (3) C: patients with MetS who were either unexposed or had relatively low exposure levels compared with higher-exposure groups. For example, physical activity was compared between sedentary patients and those engaging in light or moderate-to-high activity, and coffee consumption was compared across gradations of intake (1, 2, 3, or ≥4 cups/day) versus none; (4) O: CVD incidence, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality; (5) S: cohort or case-control studies. Exclusion criteria were: (1) studies not published in English or Korean, (2) duplicate publications, (3) conference abstracts or unpublished studies, and (4) studies in which the reference population did not consist of patients with MetS.

3. Literature Search and Selection Process

A systematic search was conducted across four international databases (PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane) and three Korean databases (RISS, NDSL, KoreaMed) from August 7, 2024 to December 1, 2024. MeSH terms in PubMed, Subject Headings in CINAHL, and Emtree terms in Embase were incorporated into the search strategy. Search terms included “metabolic syndrome,” “cohort study” (longitudinal stud* OR cohort stud*), “case-control study” (case-control stud* OR case-controlled stud*), and “follow-up” (follow-up stud* OR follow-up*), aligned with the PECOS framework (

Supplementary Data 1). Synonyms and related terminology were verified for each database. Reference lists of the retrieved articles were also manually screened to identify additional eligible studies.

Duplicate articles retrieved from all databases were removed using EndNote ver. 20 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Three authors (DEL, ML, and DY) independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts. Any discrepancies identified during the initial screening were re-evaluated in a secondary review by the same authors. Remaining disagreements after the secondary review were resolved through discussion with a fourth author (HL), who facilitated consensus-building.

Three authors (DEL, ML, and DY) independently extracted data on study characteristics and outcome variables. Extracted information included first author, publication year, country, study design, sample size, mean age, sex distribution, MetS diagnostic criteria, follow-up duration, exposure variables, and outcome measures. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion among the three authors.

4. Quality Assessment of Included Studies

Study quality was evaluated using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) across the selection, comparability, and outcome domains. Items in the selection domain were marked with a “+” when high-quality criteria were met. For representativeness of the exposed cohort, studies including at least 200 subjects were considered representative [

17]. In the comparability domain, one “+” was assigned when exposed and unexposed groups were matched at the design stage and sex was adjusted as a covariate; an additional “+” was given when other covariates were adjusted, up to a maximum of two “+” marks [

18]. In the outcomes domain, each high-quality criterion was assigned a “+,” and a minimum follow-up duration of 5 years was considered adequate [

19]. A study received a “+” in the adequacy-of-follow-up category when the number and reasons for loss to follow-up were reported. According to NOS guidelines, studies were classified as good quality with 3–4 “+” in selection, 1–2 in comparability, and 2–3 in outcomes; fair quality with two in selection, 1–2 in comparability, and 2–3 in outcomes; and poor quality with 0–1 “+” in any domain. Quality assessment was independently conducted by three authors (DEL, ML, and DY), with disagreements resolved through discussion or consultation with the fourth author (HL).

This study is a meta-analysis. In accordance with the Bioethics and Safety Act of Korea and the regulations of the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Pusan National University, this research did not involve direct intervention with human participants or the use of human-derived materials. Therefore, it was exempt from IRB review, and no application was submitted to the Pusan National University IRB.

6. Data Analysis

Meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcomes was conducted in RStudio (version 4.5.0; Posit, Boston, MA, USA) using the metafor and meta packages. Meta-analyses were carried out when identical outcome variables were reported or when effect sizes (relative risk [RR], odds ratio [OR], or hazard ratio [HR]) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were available. RR quantified relative risk, OR compared the odds of events versus non-events, and HR assessed differences in event rates over time [

20]. All ratio measures (RR, OR, HR) were log-transformed to stabilize variance and enhance comparability [

20], and pooled using random-effects models. For CVD incidence and all-cause mortality, when both HR and RR were available, HR was assumed to approximate RR under conditions of low baseline event risk; thus, RR values after log transformation were used [

21]. Standard errors were calculated using the RevMan 5.4.1 calculator. When studies presented adjusted effect estimates, adjusted values were used [

22]. Heterogeneity was assessed using the Higgins I² statistic, with thresholds of 0%, 30%–60%, and 75% indicating no, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively [

23]. Because of variability in study populations and exposures, random-effects models were chosen to improve generalizability. Sensitivity analyses included leave-one-out procedures and evaluation of Baujat plots to identify influential studies. Publication bias was assessed with funnel plots and Egger’s test [

24]. When funnel plots suggested asymmetry and Egger’s test produced

p<.05, a trim-and-fill analysis was performed [

25]. Fail-Safe N was calculated using Rosenthal’s method to estimate the number of unpublished studies needed to nullify the observed effects [

26].

RESULTS

A total of 11,956 publications were identified across seven databases. After removing 4,179 duplicates, 7,777 records were screened by title and abstract. During screening, 7,470 records were excluded based on title and 198 based on abstract, leaving 109 studies for full-text review. Of these, five full texts were unavailable, resulting in 104 articles assessed for eligibility. Following full-text evaluation, studies were excluded for the following reasons: not relevant population (n=67), not a non-pharmacological exposure (n=17), not a cohort or case-control design (n=3), not published in English or Korean (n=4), not reporting HRs, ORs, or RRs (n=2), and not using patients with MetS as the reference group (n=3). Ultimately, eight studies met the inclusion criteria. Three additional studies were identified through hand searching; one could not be retrieved, one involved an irrelevant population, and one was eligible, resulting in nine studies included in the systematic review [

7,

27-

34]. One study was excluded due to low quality, leaving eight studies for the final meta-analysis (

Figure 1).

Of the nine cohort studies, eight (88.9%) were published after 2020. Four studies (44.5%) were conducted in South Korea and three (33.3%) were conducted in China. Six studies (66.7%) included sample sizes exceeding 10,000 participants, and three studies (33.3%) reported a mean age of 55 years or older. The harmonized criteria were used to define MetS in six studies (66.7%), while the AHA, IDF, and Diabetes Society of the Chinese Medical Association criteria were each applied in one study (11.1%). Regarding exposures, physical activity was most frequently investigated (four studies, 44.5%), followed by diet (two studies, 22.2%), with lifestyle intervention, sleep, and smoking each examined in one study (11.1%). For outcomes, five studies (55.6%) reported both CVD incidence and CVD mortality, and seven studies (77.8%) reported all-cause mortality (

Table 1).

Nine cohort studies were evaluated using the NOS (

Table 2). All studies met the representativeness criteria in the selection domain. Non-exposed cohorts were drawn from the same populations as exposed groups, and exposures were primarily assessed via self-reported questionnaires. All nine studies confirmed that the outcome of interest was absent at baseline. In the comparability domain, all studies controlled for sex and additional covariates. In the outcomes domain, eight studies verified outcomes using record linkage, whereas Ye et al. [

27] relied on direct surveys. Six studies had a follow-up period of ≥5 years, while three had <5 years [

7,

27,

28]. Overall, eight studies were rated as good quality and one study as poor quality [

27].

Associations between non-pharmacological exposures and CVD incidence, CVD mortality, and all-cause mortality in MetS patients were examined (

Table 3). Meta-analysis was conducted only when three or more studies were available, which occurred only for physical activity; these results are provided in

Supplementary Data 2. Covariate adjustments varied across studies—from no adjustment to multivariable adjustment for age, sex, and additional covariates. Detailed information on subgroup classifications, exposure characteristics, reference groups, outcome types, population categories, adjustment variables, and extracted outcome counts is provided in

Supplementary Data 3 and

4.

1) CVD incidence

Four studies reported 12 effect estimates for CVD incidence [

7,

28-

30]. The pooled analysis indicated no significant association between non-pharmacological exposures and CVD incidence (RR=0.95, 95% CI, 0.81–1.10;

p=.470), with substantial heterogeneity (I²=99.3%).

2) CVD mortality

Five studies provided 20 effect estimates for CVD mortality [

30-

34]. The pooled results demonstrated a significant association between non-pharmacological exposures and reduced CVD mortality (RR=0.81, 95% CI, 0.73–0.91;

p<.001), although heterogeneity remained high (I²=81.7%).

3) All-cause mortality

Seven studies reported 27 outcomes for all-cause mortality [

28-

34]. The pooled effect showed a significant association between non-pharmacological exposures and lower all-cause mortality (RR=0.80, 95% CI, 0.75–0.85;

p<.001), with high heterogeneity (I²=94.8%).

Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot, which showed slight asymmetry (

Supplementary Data 5). Egger’s test indicated no bias for CVD incidence (

p=.292) or all-cause mortality (

p=.721), but detected bias for CVD mortality (

p=.007), prompting a trim-and-fill analysis. After imputing seven studies, the effect size shifted from HR=0.81 (95% CI, 0.73–0.91) to HR=0.93 (95% CI, 0.81–1.06), suggesting possible publication bias and the need for cautious interpretation. Fail-Safe N analysis using Rosenthal’s method yielded a fail-safe N of 36, indicating moderate robustness despite the possibility of unpublished null results [

26].

For CVD incidence, random-effects models yielded RRs ranging from 0.90 to 0.96, with heterogeneity between 98.5% and 99.4%. The Baujat plot identified Park et al. [

7] (current heavy smokers with chronic MetS) as the most influential study; excluding it reduced the pooled RR to 0.90 (95% CI, 0.80–1.01) (

Supplementary Data 6).

For CVD mortality, random-effects models produced HRs of 0.80 to 0.84, with heterogeneity ranging from 77.1% to 82.7%. The Baujat plot identified Wu et al. [

33] (coffee intake ≥4 cups/day) and Wu et al. [

34] (healthy lifestyle scores 6–8) as the most influential studies. Excluding Wu et al. [

33] resulted in an HR of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.72–0.89) with 77.9% heterogeneity, while excluding Wu et al. [

34] led to an HR of 0.84 (95% CI, 0.76–0.93) with 77.1% heterogeneity (

Supplementary Data 7).

For all-cause mortality, random-effects models yielded RRs of 0.79 to 0.82, with heterogeneity between 93.8% and 95.0%. The Baujat plot identified Lee et al. [

29] (metabolic equivalent of task [MET] score 1–499) and Wu et al. [

34] (healthy lifestyle scores 6–8) as the most influential studies. Excluding Lee et al. [

29] resulted in an RR of 0.80 (95% CI, 0.75–0.85) with 94.4% heterogeneity, while excluding Wu et al. [

34] (healthy lifestyle scores 6–8) yielded an RR of 0.82 (95% CI, 0.77–0.86) with 94.3% heterogeneity (

Supplementary Data 8).

DISCUSSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the effects of non-pharmacological exposures on the risks of CVD incidence, CVD-related mortality, and all-cause mortality among patients with MetS. Of the included studies, eight were published after 2020, reflecting a recent increase in cohort research on lifestyle factors in MetS populations. Physical activity was the most frequently investigated exposure, followed by diet, smoking, and sleep. Lifestyle modification plays a critical role in preventing and managing CVD complications in MetS. Previous studies have demonstrated that, among patients with CVD, combining pharmacological therapy with lifestyle modification yields greater improvements in cholesterol levels and blood pressure than pharmacological therapy alone [

9]. Consistent with these findings, the present study identified significant associations between non-pharmacological exposures and reduced CVD mortality and all-cause mortality, reinforcing the need to integrate lifestyle-focused guidance into education and intervention programs for MetS patients.

In this study, non-pharmacological exposures were not significantly associated with reduced CVD incidence among patients with MetS. Sensitivity analyses supported this finding; however, the Baujat plot revealed substantial heterogeneity driven by the heavy-smoker and light-to-moderate–smoker groups reported by Park et al. [

7]. This heterogeneity likely reflects differences in exposure type and covariate adjustment. Park et al. [

7] focused primarily on smoking as the main exposure and adjusted only for sex and age, whereas Ekblom-Bak et al. [

30], Lee et al. [

29], and Park et al. [

28] examined physical activity and incorporated broader multivariable adjustments. These methodological discrepancies may have contributed to the observed inconsistency. Thus, large prospective studies are needed to clarify the long-term impact of smoking history and other lifestyle factors on CVD outcomes in MetS, with attention to comprehensive exposure measurement and covariate control.

This study found that non-pharmacological exposures were associated with reductions in both CVD mortality and all-cause mortality among patients with MetS. Sensitivity analyses confirmed the stability of these associations, indicating that the findings were not driven by any individual study. However, for the lifestyle score reported by Wu et al. [

34], which combined diet, smoking, sleep, social support, and physical activity, exclusion of the 6- to 8-point category strengthened the observed association with reduced CVD mortality. This suggests that composite lifestyle indices may influence meta-analytic outcomes differently from single-exposure measures. Future research should therefore distinguish between composite indices, such as lifestyle scores, and single exposures when evaluating their impact on CVD outcomes. Furthermore, the Baujat plot indicated that the result for coffee consumption of ≥4 cups per day reported by Wu et al. [

33] and physical activity MET scores reported by Lee et al. [

29] contributed substantially to the overall heterogeneity. While Fan [

31] assessed overall dietary patterns using the alternative Mediterranean diet index score, Wu et al. [

34] focused on a single dietary factor (namely, coffee consumption). In addition, for all-cause mortality, the follow-up duration of Lee et al. [

29] was only 8 years, the shortest among the included studies. These differences in exposure definitions, measurement methods, and study design likely contributed to the observed heterogeneity.

Subgroup analyses based on characteristics of non-pharmacological exposures were attempted; however, due to the limited number of eligible studies, meta-analysis was feasible only for physical activity. The results showed that physical activity was significantly associated with reductions in both CVD mortality and all-cause mortality. Furthermore, intensity-specific analyses demonstrated that low-, moderate-, and high-intensity physical activity were all associated with lower all-cause mortality. These results align with prior findings indicating that regular physical activity reduces the risk of CVD and mortality [

28-

30,

32]. Accordingly, even low-intensity exercise should be encouraged among sedentary individuals with MetS, highlighting the importance of structured physical activity counseling by nurses. Nonetheless, given the small number of available studies, these findings should be interpreted cautiously.

In addition to physical activity, cohort studies examining smoking, sleep, and diet were identified. For smoking, both past and current smokers had higher CVD risk than non-smokers [

7]. However, because only one study was available and no information was provided on smoking duration or time since cessation, further research is needed. Sleep was also associated with cardiovascular risk, with both long sleep duration (≥9 hours) and short sleep duration (<6 hours) linked to increased risk of cerebrovascular and CVD [

27]. Regarding diet, adherence to healthier dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet has been shown in earlier research to reduce CVD risk through improvements in blood pressure and lipid profiles [

10,

31]. Similarly, Zhu et al. [

35] similarly reported that dietary exposures, including more than eight hours of sleep and a tuber-meat dietary pattern, were associated with higher MetS prevalence. These findings highlight the importance of adopting a comprehensive lifestyle modification approach, including diet, smoking cessation, adequate sleep, and physical activity, for MetS management. However, current evidence remains limited, as only one cohort study was available for both smoking and sleep, and dietary exposures were restricted to the Mediterranean diet, coffee, and tea. Therefore, future large-scale cohort studies with standardized exposure definitions, extended follow-up, and thorough covariate adjustment are necessary.

RCTs provide strong causal evidence for the short-term effects of non-pharmacological interventions, such as diet and physical activity, on cardiovascular risk factors. However, their limited duration and highly controlled settings restrict their generalizability to real-world contexts. In contrast, cohort studies allow the evaluation of long-term effects of lifestyle factors on cardiovascular outcomes under naturalistic conditions [

14]. The present study is therefore significant in that it integrates cohort data to clarify the long-term impact of non-pharmacological exposures on patients with MetS, thereby complementing short-term evidence derived from experimental trials.

Nevertheless, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, only eight studies were included in the meta-analysis, which restricted subgroup analyses to physical activity alone. Further research is needed to examine the long-term effects of other non-pharmacological factors—such as diet, smoking, and sleep—on CVD outcomes in MetS populations. Second, the limited number of eligible studies prevented the use of meta-regression, constraining a more detailed investigation of heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses were conducted to partially address this issue, but the inability to apply meta-regression remains an important limitation. Third, for CVD mortality, publication bias could not be excluded based on the funnel plot and Egger’s regression test, indicating that the findings should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, potential publication bias may have been present because gray literature, including dissertations, was not included in the search. Finally, for CVD mortality, Egger’s test again suggested potential publication bias, reinforcing the need for cautious interpretation of the results.

CONCLUSION

This systematic review and meta-analysis confirm that non-pharmacological exposures are associated with reduced cardiovascular and all-cause mortality among patients with MetS. Physical activity, in particular, demonstrated protective effects against both CVD incidence and all-cause mortality, with consistent benefits observed across light-, moderate-, and high-intensity activity levels. These findings suggest that incorporating education and interventions focused on non-pharmacological exposures, alongside pharmacological treatment, may help prevent and manage complications in patients with MetS. However, due to the limited number of eligible studies, subgroup analyses examining smoking, sleep, and diet could not be performed. As additional evidence emerges, future research should further investigate the long-term effects of individual non-pharmacological factors, specifically diet, smoking, and sleep, by evaluating their respective contributions to CVD outcomes in populations with MetS.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and/or design acquisition - HL, DEL, SJ, and ML; analysis - HL, DEL, SJ, and ML; interpretation of the data - HL, DEL, SJ, and ML; and drafting or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content - HL and DEL.

-

Funding

This work was supported by a 2-Year Research Grant of Pusan National University.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to Dayun Lee for the invaluable support in reviewing the literature during the meta-analysis.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data can be obtained from the corresponding authors.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Figure 1.Flow diagram of the study selection process.

Table 1.Descriptive Summary of the Included Studies (K=9)

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

n (%) |

|

Publication year |

<2020 |

1 (11.1) |

|

≥2020 |

8 (88.9) |

|

Publication country |

China |

3 (33.3) |

|

Korea |

4 (44.5) |

|

Norway |

1 (11.1) |

|

Sweden |

1 (11.1) |

|

Sample size |

<10,000 |

3 (33.3) |

|

≥10,000 |

6 (66.7) |

|

Study design |

Cohort |

9 (100.0) |

|

Mean age of participants |

<55 |

4 (44.5) |

|

≥55 |

3 (33.3) |

|

Not reported |

2 (22.2) |

|

Definition of MetS |

American Heart Association |

1 (11.1) |

|

Harmonized definition |

6 (66.7) |

|

International Diabetes Foundation |

1 (11.1) |

|

The Diabetes Society of Chinese Medical Association |

1 (11.1) |

|

Type of exposure |

Diet |

2 (22.2) |

|

Lifestyle intervention |

1 (11.1) |

|

Physical activity |

4 (44.5) |

|

Sleeping |

1 (11.1) |

|

Smoking |

1 (11.1) |

|

Outcomes |

CVD incidence†

|

5 (55.6) |

|

Mortality |

|

|

All-cause†

|

7 (77.8) |

|

CVD†

|

5 (55.6) |

Table 2.Quality Assessment of Included Studies using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale Cohort Studies (K=9)

|

Author (year) |

Selection |

Comparability |

Outcome |

Quality rating |

|

A |

B |

C |

D |

Sub-sum |

E |

Sub-sum |

F |

G |

H |

Sub-sum |

|

Ekblom-Bak et al. (2021) [30] |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

3 |

++ |

2 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

3 |

Good |

|

Fan et al. (2023) [31] |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

3 |

++ |

2 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

3 |

Good |

|

Lee et al. (2023) [29] |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

3 |

++ |

2 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

3 |

Good |

|

Park et al. (2021) [7] |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

3 |

++ |

2 |

+ |

− |

+ |

2 |

Good |

|

Park et al. (2020) [28] |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

3 |

++ |

2 |

+ |

− |

+ |

2 |

Good |

|

Stensvold et al. (2011) [32] |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

3 |

++ |

2 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

3 |

Good |

|

Wu et al. (2023) [33] |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

3 |

++ |

2 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

3 |

Good |

|

Wu et al. (2022) [34] |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

3 |

++ |

2 |

+ |

+ |

+ |

3 |

Good |

|

Ye et al. (2020) [27] |

+ |

+ |

− |

+ |

3 |

++ |

2 |

− |

− |

+ |

1 |

Poor |

Table 3.Effects of Non-pharmacological Factors over Follow-up Duration (K=8)

|

Outcomes |

Total |

|

k |

Pooled HR or RR (95% CI; p) |

I2 (p) |

|

CVD incidence†

|

4 |

0.95 (0.81–1.10; .470)§

|

99.3% (<.001) |

|

CVD mortality†

|

5 |

0.81 (0.73–0.91; <.001)‡

|

81.7% (<.001) |

|

All-cause mortality†

|

7 |

0.80 (0.75–0.85; <.001)§

|

94.8% (<.001) |

REFERENCES

- 1. Radhakrishnan J, Swaminathan N, Pereira NM, Henderson K, Brodie DA. Acute changes in arterial stiffness following exercise in people with metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2017;11(4):237-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2016.08.013

- 2. Noubiap JJ, Nansseu JR, Lontchi-Yimagou E, Nkeck JR, Nyaga UF, Ngouo AT, et al. Geographic distribution of metabolic syndrome and its components in the general adult population: a meta-analysis of global data from 28 million individuals. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;188:109924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109924

- 3. Kim HJ, Kang DR, Kim JY, Kim W, Jeong YW, Chun KH, et al; The Taskforce Team of the Metabolic Syndrome Fact Sheet of the Korean Society of Cardiometabolic Syndrome. Metabolic syndrome fact sheet 2024: executive report. Cardiometab Syndr J. 2024;4(2):70-80. https://doi.org/10.51789/cmsj.2024.4.e14

- 4. Alshammary AF, Alharbi KK, Alshehri NJ, Vennu V, Ali Khan I. Metabolic syndrome and coronary artery disease risk: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4):1773. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041773

- 5. Bang SY. The effects of metabolic syndrome on quality of life. J Korea Acad Ind Coop Soc. 2015;16(10):7034-42. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2015.16.10.7034

- 6. Kim KY, Dong JY, Han SY, Lee KS. The effects of the metabolic syndrome on the total medical charge. Health Policy Manag. 2017;27(1):47-55. https://doi.org/10.4332/KJHPA.2017.27.1.47

- 7. Park S, Han K, Lee S, Kim Y, Lee Y, Kang MW, et al. Smoking, development of or recovery from metabolic syndrome, and major adverse cardiovascular events: a nationwide population-based cohort study including 6 million people. PLoS One. 2021;16(1):e0241623. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241623

- 8. Aboaba AO, Okoro MC, Okobi OE, Falade IM, Ogbeifun OE, Katas S, et al. Comparative efficacy of lifestyle modifications versus pharmacotherapy on weight loss and metabolic health outcomes: a comprehensive review. J Biosci Med. 2024;12(7):17-29. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbm.2024.127003

- 9. Abate SM, Thanigaimani S, Sinha M, Sun D, Golledge J. A systematic review and meta-analysis testing the effect of lifestyle modification and medication optimization programs on cholesterol and blood pressure in patients with cardiovascular disease. Syst Rev. 2025;14(1):153. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-025-02857-5

- 10. Papadaki A, Nolen-Doerr E, Mantzoros CS. The effect of the Mediterranean diet on metabolic health: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials in adults. Nutrients. 2020;12(11):3342. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113342

- 11. Wewege MA, Thom JM, Rye KA, Parmenter BJ. Aerobic, resistance or combined training: a systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise to reduce cardiovascular risk in adults with metabolic syndrome. Atherosclerosis. 2018;274:162-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.05.002

- 12. Kim HJ, Cho YJ. Smoking cessation and risk of metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103(22):e38328. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000038328

- 13. Xie J, Li Y, Zhang Y, Vgontzas AN, Basta M, Chen B, et al. Sleep duration and metabolic syndrome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2021;59:101451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101451

- 14. Bosdriesz JR, Stel VS, van Diepen M, Meuleman Y, Dekker FW, Zoccali C, et al. Evidence-based medicine-when observational studies are better than randomized controlled trials. Nephrology (Carlton). 2020;25(10):737-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/nep.13742

- 15. Kim SY, Park JE, Seo HJ, Lee YJ, Jang BH, Son HS, et al. NECA’s guidance for undertaking systematic reviews and meta-analyses for intervention [Internet]. Seoul: National Evidence based Healthcare Collaborating Agency; 2021 [cited 2025 September 1]. Available from: https://www.scribd.com/document/466743273/NECA-MENUAL-%EC%B2%B4%EA%B3%84%EC%A0%81-%EB%AC%B8%ED%97%8C%EA%B3%A0%EC%B0%B0-%EB%A7%A4%EB%89%B4%EC%96%BC

- 16. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- 17. National Institute of Health. Chronic disease cohort studies: pulmonary hypertension cohort [Internet]. Cheongju: NIH; 2024 [cited 2024 October 22]. Available from: https://nih.go.kr/ko/main/contents.do?menuNo=300934

- 18. Gouveia ER, Gouveia BR, Marques A, Peralta M, Franca C, Lima A, et al. Predictors of metabolic syndrome in adults and older adults from Amazonas, Brazil. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):1303. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18031303

- 19. Seoul Metropolitan Government. Prediction of cardiovascular diseases using metabolic syndrome severity scores [Internet]. Seoul: Seoul Metropolitan Government; 2021 [cited 2025 July 3]. Available from: https://5check.seoul.go.kr/webzine/2101/2/4page.html

- 20. George A, Stead TS, Ganti L. What’s the risk: differentiating risk ratios, odds ratios, and hazard ratios? Cureus. 2020;12(8):e10047. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.10047

- 21. Weir IR, Marshall GD, Schneider JI, Sherer JA, Lord EM, Gyawali B, et al. Interpretation of time-to-event outcomes in randomized trials: an online randomized experiment. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(1):96-102. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdy462

- 22. Higgins JP, Li T, Deeks JJ. Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. In: Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, , editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2019. p. 143-76.

- 23. Deeks JJ, Higgins JP, Altman DG. Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In: Higgins JP, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, , editors. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2019. p. 241-84.

- 24. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-34. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

- 25. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):455-63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x

- 26. Rosenberg MS. The file-drawer problem revisited: a general weighted method for calculating fail-safe numbers in meta-analysis. Evolution. 2005;59(2):464-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0014-3820.2005.tb01004.x

- 27. Ye Y, Zhang L, Wang A, Wang Y, Wang S, Ning G, et al. Association of sleep duration with stroke, myocardial infarction, and tumors in a Chinese population with metabolic syndrome: a retrospective study. Lipids Health Dis. 2020;19(1):155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-020-01328-1

- 28. Park S, Han K, Lee S, Kim Y, Lee Y, Kang MW, et al. Association between moderate-to-vigorous physical activity and the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events or mortality in people with various metabolic syndrome status: a nationwide population-based cohort study including 6 million people. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(22):e016806. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.120.016806

- 29. Lee CH, Han KD, Kwak MS. Physical activity has a more beneficial effect on the risk of all-cause mortality in patients with metabolic syndrome than in those without. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2023;15(1):255. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01227-2

- 30. Ekblom-Bak E, Halldin M, Vikstrom M, Stenling A, Gigante B, de Faire U, et al. Physical activity attenuates cardiovascular risk and mortality in men and women with and without the metabolic syndrome: a 20-year follow-up of a population-based cohort of 60-year-olds. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2021;28(12):1376-85. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487320916596

- 31. Fan H, Wang Y, Ren Z, Liu X, Zhao J, Yuan Y, et al. Mediterranean diet lowers all-cause and cardiovascular mortality for patients with metabolic syndrome. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2023;15(1):107. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01052-7

- 32. Stensvold D, Nauman J, Nilsen TI, Wisloff U, Slordahl SA, Vatten L. Even low level of physical activity is associated with reduced mortality among people with metabolic syndrome, a population based study (the HUNT 2 study, Norway). BMC Med. 2011;9:109. https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-9-109

- 33. Wu E, Bao YY, Wei GF, Wang W, Xu HQ, Chen JY, et al. Association of tea and coffee consumption with the risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality among individuals with metabolic syndrome: a prospective cohort study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2023;15(1):241. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13098-023-01222-7

- 34. Wu E, Ni JT, Zhu ZH, Xu HQ, Tao L, Xie T. Association of a healthy lifestyle with all-cause, cause-specific mortality and incident cancer among individuals with metabolic syndrome: a prospective cohort study in UK Biobank. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):9936. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19169936

- 35. Zhu H, Zhang L, Zhu T, Jia L, Zhang J, Shu L. Impact of sleep duration and dietary patterns on risk of metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and elderly adults: a cross-sectional study from a survey in Anhui, Eastern China. Lipids Health Dis. 2024;23(1):361. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-024-02354-z