Abstract

-

Purpose

This study aimed to investigate the mediating role of patient safety perception (PSP) in the relationship between the right to know (RtK) and patient participation (PP) among inpatients.

-

Methods

This descriptive study used a convenience sample of inpatients from three small and medium-sized hospitals in October 2023. A total of 231 inpatients completed a self-report questionnaire assessing PP, RtK, and PSP. Data were analyzed using a mediation model with the PROCESS Macro (Model 4), applying 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals.

-

Results

The findings revealed significant positive correlations between PP and RtK (r=.78, p<.001) and PSP (r=.83, p<.001). Both RtK and PSP had significant effects on PP. PSP was identified as an important mediator in the relationship between RtK and PP (B=.35, boot standard error=.06, 95% confidence interval=.27–.44). The findings confirm that inpatients’ RtK is associated with improved PSP and increased PP.

-

Conclusion

These findings highlight the critical role of safeguarding patients’ right to information as a strategy for promoting patient safety. To ensure safe and effective care in small and medium-sized hospitals, ongoing support is essential for developing and systematically implementing patient safety education initiatives that actively involve patients.

-

Key Words: Inpatients; Patient safety; Patient participation; Perception; Patient rights

INTRODUCTION

As medical technology advances and average life expectancy increases, patients visiting hospitals are becoming more conscious and informed about the safety of medical services. Patient safety is defined as “a framework of organized activities that create a culture, process, behavior, technology, and environment that consistently and sustainably reduces risks in health care, reduces avoidable harm, reduces the likelihood of errors, and influences harm when it occurs” [

1]. To prevent incidents threatening patient safety, medical institutions conduct various patient safety activities such as fall prevention and management, bedsore management, infection management, drug management, fire prevention, and hand hygiene [

2]. According to the Patient Safety Act, medical institutions must establish patient safety committees, assign personnel to perform patient safety activities, and voluntarily report patient safety incidents [

3].

Tertiary and large general hospitals carry out patient safety activities through dedicated patient safety personnel, as well as through patient safety planning and education [

4]. However, small and medium-sized hospitals face challenges such as insufficient dedicated nursing staff for patient safety and difficulties in fulfilling these roles [

5]. Small and medium-sized hospitals are classified as general medical institutions with fewer than 300 beds [

6,

7]. According to the Korea Medical Institutions Accreditation Board, only 173 of the 301 small and medium-sized acute hospitals passed the accreditation evaluation system [

6], making effective patient safety activities challenging [

2]. Previous studies have also reported that patient safety activity scores among nurses in small and medium-sized hospitals are lower compared to those in large hospitals [

8]. Nevertheless, patient safety research predominantly focuses on healthcare staff [

9,

10] and inpatients in tertiary and large general hospitals [

11-

15]. Although patient safety research targeting nurses in small and medium-sized hospitals is conducted [

8,

16], studies specifically examining inpatients in these hospitals are very limited [

7]. Therefore, a research gap exists regarding inpatient perspectives and awareness of patient safety in small and medium-sized hospitals.

The World Health Organization emphasizes the role of patients directly affected by patient safety incidents in improving overall patient safety [

17]. Thus, patient participation (PP) is gaining attention as a potential pathway for strengthening patient safety. PP refers to the opportunities for patients to engage in and influence decisions about their own treatment through dialogue with healthcare professionals, incorporating patients’ preferences and experiential knowledge [

18]. Previous studies have demonstrated that involving patients and their families in treatment procedures helps prevent adverse events and medical errors, thereby reducing patient safety incidents [

19,

20]. Since patients directly suffer from the consequences of safety incidents, such as pain or long-term harm, ongoing communication and active participation in decision-making with healthcare providers throughout treatment are crucial [

20]. Specifically, patient and family participation positively influences clinical outcomes, including mortality, readmission rates, and length of hospital stays [

21]. Thus, for patient safety improvement, patients must maintain continuous interest in their treatment and actively participate [

18]. In other words, PP is an effective strategy to overcome the limitations inherent in patient safety management primarily centered around medical staff, highlighting the need to promote active participation among inpatients.

The right to know (RtK) is a fundamental human right. Patients can exercise self-determination effectively when they receive sufficient explanations from medical staff regarding their illnesses, planned tests, medications, and treatment plans [

22]. Adequate information fulfills the patient's RtK, enabling them to better manage the treatment process and achieve positive clinical outcomes [

23]. However, the asymmetrical relationship between patients and medical staff remains a significant barrier to fulfilling the RtK [

12]. Furthermore, due to information overload, the complexity and specialized nature of medical care, and the inherent informational asymmetry between patients and medical staff, patients’ rational decision-making abilities are limited, leading them to rely heavily on medical professionals’ judgments [

23]. Previous studies indicate that effective communication between patients and medical staff guarantees patients’ treatment decision-making rights and significantly enhances satisfaction with medical services [

24]. In particular, providing relevant information about treatment decisions, including comparative treatment options, safety assurances, and acknowledgment of the patient’s RtK, is crucial [

24]. Such communication enables patients to gather and utilize treatment-related information more effectively. Patients’ RtK also positively influences their perception of patient safety [

25]. Thus, it can be inferred that fulfilling patients’ RtK improves their patient safety perception (PSP), subsequently increasing their participation in treatment decisions.

To increase PP among inpatients, they must be educated to recognize safety as an essential issue in medical institutions [

13]. PSP refers to the extent to which inpatients recognize they are safe in medical settings; it represents the patient’s view and acceptance of their own safety [

12,

13]. Consequently, a high PSP indicates the patient feels safe. Previous studies indicate that PSP improves through patient safety education aimed at the general public [

18], and hospitalized patients’ positive experiences also significantly enhance PSP [

26]. Furthermore, higher PSP among hospitalized patients is associated with increased PP [

14,

27]. Therefore, patient safety is a critical concern for both patients and their guardians, with PSP playing a significant role in promoting PP.

Summarizing previous research, inpatients’ RtK positively affects PSP [

25], and PSP positively influences PP [

14,

27]. Currently, no studies specifically examine the relationship between RtK and PP among inpatients; however, it has been established that RtK is associated with PP in self-determination [

22]. When patients’ RtK is satisfied, it potentially facilitates PP, subsequently contributing to patient safety improvements. Thus, understanding patients’ RtK and their awareness of patient safety is critical for identifying factors that enhance PP. Studies examining patient safety awareness as a mediating variable have found it mediates the relationship between inpatients’ health literacy and PP [

15]. Nonetheless, there is limited research exploring how patient safety awareness functions as a mediator in affecting PP. Consequently, understanding the factors influencing PP, as well as the relationship between patients’ RtK and patient safety awareness, is vital for developing interventions aimed at enhancing PP. Therefore, this study aims to clarify the importance of PP in improving patient safety among inpatients by establishing and analyzing a mediation model of patient safety awareness in the relationship between the inpatients’ RtK and PP.

The specific objectives were as follows: first, to investigate differences in RtK, PSP, and PP according to the general characteristics of inpatients; second, to analyze the correlations among RtK, PSP, and PP among inpatients; and third, to examine the mediating role of PSP in the relationship between RtK and PP among inpatients.

METHODS

1. Research Design

A descriptive study design was used to investigate the mediating effect of PSP on the relationship between the RtK and PP among inpatients in small and medium-sized hospitals. This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the STROBE guidelines.

2. Research Participants

Participants were selected using convenience sampling from three small and medium-sized hospitals located in Seoul. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) adults aged 20–65 years, (2) at least two hospitalizations, (3) experience of procedures or surgery, and (4) ability to independently read and complete the questionnaire. Exclusion criteria included: (1) diagnosis from a psychiatrist, and (2) inability to understand the questionnaire due to cognitive impairment. The required sample size was determined using G*Power 3.1.9.7, specifying regression analysis for mediating effects with a medium effect size (.15), significance level (.05), and power (.95). The minimum calculated sample size was 184, considering 12 independent variables. Accounting for a 20% dropout rate, 230 questionnaires were initially distributed. Data from 240 participants were collected, with nine excluded due to not meeting inclusion criteria or providing insincere responses, resulting in a final analyzed sample of 231 participants.

3. Measurements

1) Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

A structured questionnaire captured sociodemographic characteristics (sex, age, education, occupation, marital status, hospital visit frequency) and clinical characteristics (underlying diseases, patient safety incidents, patient safety education).

2) Right to know (RtK)

RtK was measured using the RtK Scale, modified from Choi and Lee’s study [

28] based on the Perception of RtK Scale developed by Ahn et al. [

22]. This scale comprises 23 items grouped into five sub-factors: existence of legal and institutional frameworks related to RtK (1 item), regulatory effects and granted rights (6 items), doctors’ explanatory duties and their binding nature (6 items), perception of RtK (8 items), and realization of RtK in hospitals (2 items). Each item employed a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” (1 point) to “definitely” (5 points), resulting in scores ranging from 23 to 115, with higher scores indicating greater RtK perception. Cronbach’s α reliability was .90 in Choi and Lee’s study [

28] and .89 in the current study.

3) Patient safety perception (PSP)

PSP was assessed using the PSP Scale, validated by Kim et al. [

13] for Korean inpatients based on the Patient Measure of Safety developed by Giles et al. [

29]. The scale consists of 24 items divided into three sub-factors: safety assurance activities (9 items), safety practices (10 items), and trust in the medical system (4 items). Items used a 5-point Likert scale from “very dissatisfied” (1 point) to “very much so” (5 points), with total scores ranging from 24 to 120 points. Higher scores indicated greater PSP. Cronbach’s α reliability was .93 in the study of Kim et al. [

13] and .94 in the current study.

4) Patient participation (PP)

PP was evaluated using the PP Scale (PPS), developed by Song and Kim [

18] for Korean outpatients and inpatients. The PPS consists of 21 items grouped into four sub-factors: information and knowledge sharing (8 items), participation in decision-making processes (2 items), proactive self-management activities (7 items), and establishment of mutual trust (4 items). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from “not at all” (1 point) to “very much so” (5 points). Scores ranged from 21 to 105, with higher scores indicating greater PP. Cronbach’s α reliability was .92 in Song and Kim’s study [

18] and .93 in this study.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Sahmyook University (IRB No. SYU 2023-08-008-005) of the affiliated university. Data collection occurred from October 2 to October 20, 2023. The researcher visited three small and medium-sized hospitals, secured cooperation, and posted recruitment notices in each ward. Research assistants, trained on study objectives and procedures, verified participants’ eligibility, explained study purposes and procedures, and obtained informed consent for participation. The research explanation included the study purpose and methods, the selection criteria for the participants, the voluntary nature of research participation, the right to stop participating at any time, and the fact that the collected data would be used only for research purposes. A URL link was sent to participants who read the explanation and agreed to participate. Participants began the survey by checking the consent box. Those who completed the survey received an online gift card as a token of appreciation.

5. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS/WIN 25.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Frequency analysis and descriptive statistics summarized participants’ general characteristics and measured variables. Differences based on general characteristics were assessed through independent t-tests and analysis of variance, followed by Scheffé’s post-hoc tests. Pearson’s correlation analysis evaluated relationships among RtK, PSP, and PP. Mediation analysis utilized Model 4 of the SPSS PROCESS Macro Procedure (version 4.1), employing bootstrapping to calculate a 95% confidence interval (CI). Effects were deemed significant if the CI excluded zero [

30].

RESULTS

1. General Characteristics of the Participant

Table 1 presents the general characteristics of the participants. The study included 81 males (35.1%) and 150 females (64.9%). The age distribution was as follows: 114 patients (49.4%) were aged 31–40 years, 51 patients (22.1%) were aged 21–30 years, 43 patients (18.6%) were aged 41–50 years, and 23 patients (10.0%) were aged 51 years or older. Most participants were employed (n=196, 84.8%), and 116 patients (50.2%) were single. A total of 161 patients (69.7%) reported no underlying disease, exceeding those who reported underlying diseases (n=70, 30.3%). The most common frequency of hospital visits was once every 3 months (n=78, 33.8%), and the majority had been hospitalized twice (n=107, 46.3%). Most participants reported no experience with patient safety incidents (n=204, 88.3%) and had received patient safety education (n=207, 89.6%).

2. Differences in RtK, PSP, and PP Based on General Characteristics

Table 2 shows differences in measured variables according to general characteristics. RtK significantly varied by sex (t=−5.14,

p<.001), age (F=19.21,

p<.001), education level (t=−3.36,

p=.002), occupation (t=2.34,

p=.020), marital status (t=−5.21,

p<.001), frequency of hospital visits (F=9.84,

p<.001), and frequency of hospitalizations (F=8.63,

p<.001). Post hoc analysis indicated higher RtK scores among patients in their 20s compared to those in their 30s and 40s, and patients aged 51 years or older had higher RtK scores compared to those in their 40s. Additionally, patients visiting the hospital once a year had higher RtK scores than those visiting more frequently, and those hospitalized twice reported higher RtK scores compared to those hospitalized three or more times.

PSP significantly differed by sex (t=−2.47, p=.014), age (F=6.81, p<.001), marital status (t=−4.95, p<.001), underlying disease (t=2.43, p=.016), frequency of hospital visits (F=5.80, p=.001), frequency of hospitalizations (F=13.52, p<.001), patient safety incident experience (t=3.25, p=.001), and patient safety education experience (t=−3.24, p=.001). Post hoc tests showed higher PSP scores in patients in their 20s compared to those in their 30s and 40s, patients visiting once a year compared to those visiting once every 6 months, and patients hospitalized twice compared to those hospitalized three or more times.

PP significantly varied by sex (t=−3.83, p<.001), age (F=9.82, p<.001), education level (t=−2.85, p=.006), marital status (t=−4.88, p<.001), underlying disease (t=2.76, p=.006), frequency of hospital visits (F=6.98, p<.001), and frequency of hospitalizations (F=9.66, p<.001). Post hoc analyses revealed higher PP scores for patients in their 20s compared to those in their 30s, higher scores for those in their 30s compared to those in their 40s, and higher scores among patients aged 51 or older compared to those in their 40s. Patients visiting once monthly or yearly had higher PP scores compared to those visiting once every 6 months, and those hospitalized twice had higher scores compared to those hospitalized three or more times.

3. Correlation among RtK, PSP, and PP

Table 3 presents correlations and descriptive statistics for RtK, PSP, and PP. The mean scores were 3.96 (±0.47) for RtK, 4.31 (±0.45) for PSP, and 4.33 (±0.45) for PP. Significant positive correlations were found between RtK and PSP (r=.68,

p<.001), RtK and PP (r=.78,

p<.001), and PSP and PP (r=.83,

p<.001).

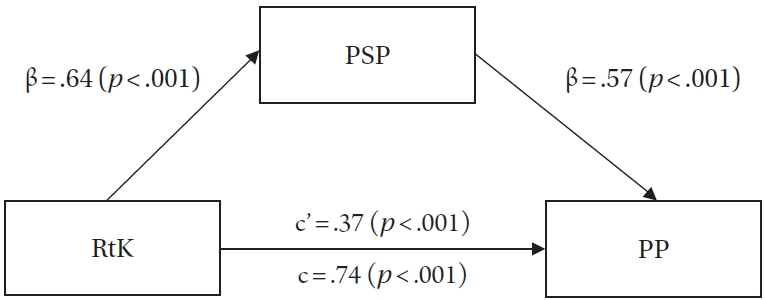

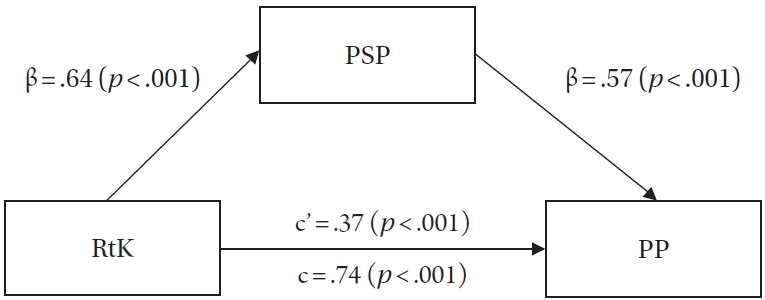

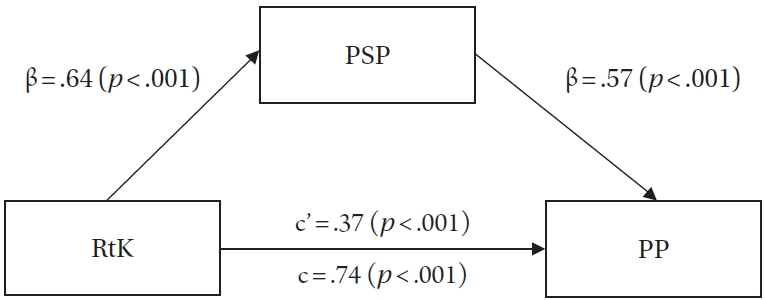

4. The Mediating Effect of PSP in the Relationship between the RtK and PP

Prior to mediation analysis, regression assumptions were verified. Skewness values for RtK, PSP, and PP were within ±2, and kurtosis values were under 7, confirming normality (

Table 3). Durbin-Watson was 1.99, and variance inflation factor ranged from 1.25 to 2.31, indicating no autocorrelation or multicollinearity. Mediating effects were examined using the PROCESS Macro (Model 4), controlling for significant variables (sex, age, education, marital status, underlying disease, hospital visit frequency, and hospitalization frequency).

In Step 1, the independent variable, the RtK, had a significant positive effect on the mediating variable, PSP (β=.64,

p<.001). In Step 2, RtK had a significant positive effect on the dependent variable, PP (β=.74,

p<.001). In Step 3, the RtK had a significant positive effect on PP (β=.37,

p<.001), and the mediating variable, PSP, had a significant effect on PP (β=.57,

p<.001). The explanatory power of the final model was 80.2% (adjusted R

2=.802, F=73.38,

p<.001) (

Table 4).

The indirect mediating effect of PSP was statistically significant because the 95% CI did not include 0 (B=.35, boot standard error=.06, 95% CI=0.27–0.44). In other words, it was confirmed that when perceptions of the RtK increased, PSP also increased, which could lead to higher levels of PP. The results of our research model are presented in

Figure 1.

DISCUSSION

This study confirmed the mediating effect of PSP in the relationship between RtK and PP among inpatients in small and medium-sized hospitals. The results showed that inpatients’ RtK was positively associated with increased PSP and PP.

First, PSP was identified as a mediator in the relationship between inpatients’ RtK and their participation. Specifically, it was demonstrated that RtK perception directly increased PP and that PSP further enhanced PP as a mediator. These findings partially align with previous studies indicating that higher PSP contributes to increased PP [

14,

27]. Prior research highlighted that patients believe being informed about their health enhances communication with healthcare providers, ultimately improving patient safety [

31]. However, hospitalized patients often exhibit limited understanding of specific patient safety activities despite acknowledging their importance [

7]. This may suggest that the passive role typically assumed by hospitalized patients leads to reduced awareness and engagement regarding patient safety management [

32]. Therefore, targeted measures are needed to increase PSP, enabling patients to identify and participate effectively in safety activities crucial to their own well-being.

Second, PSP among patients admitted to small and medium-sized hospitals differed significantly based on sex, age, marital status, underlying diseases, frequency of hospital visits, hospitalizations, experience with patient safety incidents, and patient safety education. These findings are consistent with previous studies involving patients admitted to hematology and oncology departments [

14], general hospitals [

12], and the general public [

27]. Additionally, previous studies reported that positive patient experiences [

26], more favorable RtK perceptions and greater self-determination [

25], and effective patient safety education [

27] significantly improve PSP scores. PSP is influenced by both patient characteristics and environmental factors, such as healthcare institution systems, facilities, and programs. Patient experiences can enhance familiarity with institutional procedures and facilitate communication with medical staff. Past research emphasizes the close relationship between PSP and PP [

15,

18], highlighting patient safety education and RtK perceptions as critical components in promoting patient engagement. This study also underscores the importance of patient safety education, as PSP scores were higher among patients who received such education. This suggests that patient safety education provided by medical institutions effectively enhances patients’ knowledge and coping skills within healthcare environments. Patients in small and medium-sized hospitals generally prefer personalized, one-on-one education from medical staff over videos or leaflets [

7]. Thus, developing patient safety education programs tailored to the unique characteristics and complex factors of patients in smaller hospitals is necessary. Accordingly, revising the Patient Safety Act, currently applicable only to institutions with 200 or more beds, to include mandatory patient safety personnel for smaller hospitals is essential. Additionally, national policy support is crucial for promoting patient safety activities and improving the quality of patient safety education. Such policy initiatives will strengthen patient safety efforts in small and medium-sized hospitals and significantly enhance the quality of patient safety education.

Third, this study analyzed the effect of RtK on patients’ PSP and participation, identifying a direct effect. Additionally, significant differences in RtK were observed based on sex, age, educational level, occupation, marital status, frequency of hospital visits, and hospitalization frequency. These findings align with previous research showing RtK differences by sex (female), age (20s), and educational level [

22,

25]. Although there is limited evidence explicitly demonstrating the impact of inpatients’ RtK on PP, existing research confirms that higher RtK scores significantly enhance PSP [

25]. Furthermore, a study of adults over 20 years old reported that RtK mediated satisfaction with medical services; patient satisfaction increased when medical staff provided sufficient explanations and tailored information according to patient-specific physical and social characteristics [

24]. Interviews with patients aged over 60 revealed increased PP correlated with greater awareness of medical information about their condition [

31]. Clear understanding of illness-related medical information enhances patients’ self-efficacy and risk perception, thereby encouraging proactive safety behaviors [

32]. RtK closely relates to the right to access and understand health information, ensuring patients are informed about their health [

22]. Health literacy complements RtK, encompassing abilities to access, comprehend, evaluate, and use health information effectively for personal health management [

15]. Previous studies have demonstrated health literacy’s significant influence on PP [

15], partially supporting the current findings regarding RtK. These results underscore the importance of appropriate health literacy and RtK about their condition, suggesting patients without these may struggle with effective health management. Therefore, providing tailored medical information based on age and education level, fostering an open safety culture where patients freely inquire about and verify treatment processes, and establishing a system to ensure that medical staff adequately inform patients are essential for promoting active PP.

Finally, this study confirmed differences in PP among inpatients in small and medium-sized hospitals based on sex, age, education level, marital status, underlying diseases, frequency of hospital visits, and hospitalization frequency. These findings partially align with previous research demonstrating PP variations according to age, education level, occupation, and underlying diseases among inpatients [

14]. Active patient and family participation in the treatment process reportedly reduces patient safety incidents and positively affects clinical outcomes, including reduced mortality and readmission rates [

19-

21]. Major factors influencing PP include patient-staff relationships, patient safety incident experiences, and medical institution systems [

12]. Patient safety education specifically increased PP [

33]. Effective patient safety education should include practical, patient-performed actions, such as using memo sheets and preparation cards to help patients clarify questions about treatment and confirm medications, hospitalization, and surgery [

33]. Thus, continuous support and management are needed to implement varied patient safety education strategies directly involving patients. However, hierarchical relationships with medical staff present barriers to PP [

23]. With the rise of patient-centered care concepts, general and tertiary hospitals emphasize patient-centered nursing care, fostering therapeutic relationships and active patient engagement, positively influencing health outcomes and quality of life [

34]. Implementing patient-centered nursing care in smaller hospitals requires multifaceted efforts to eliminate communication barriers between patients and healthcare professionals. Specifically, patients must recognize their critical role in ensuring patient safety and actively participate in treatment decision-making, promoting effective patient safety practices, thus fostering a robust safety culture.

This study has several limitations. First, since it targeted only three small and medium-sized hospitals in Seoul, South Korea, regional bias may limit generalizability. Future studies should expand sampling to include hospitals from other regions to obtain more representative data. Second, inpatient characteristics vary significantly across small and medium-sized hospitals due to structural differences (facilities, staffing, bed count), potentially affecting RtK and PSP. Factors such as diagnosis, severity, surgical procedures, and pain management were not explored regarding their influence on PP. Subsequent studies should investigate and control these factors to enhance result generalizability. Lastly, conducting patient safety research among inpatients in smaller hospitals substantially contributes to medical service quality improvement. Thus, it is essential to develop and verify interventions aimed at increasing PP, incorporating RtK and PSP elements. Such research will provide critical evidence for strengthening patient safety culture and encouraging PP in these healthcare settings.

CONCLUSION

This study confirmed the mediating role of PSP in the relationship between the RtK and PP. Specifically, inpatients’ RtK was shown to promote PP through enhanced PSP. Additionally, RtK was positively correlated with both PSP and PP, indicating that ensuring patients’ RtK is essential for improving patient safety. It is particularly significant to recognize the necessity of developing targeted interventions to build and enhance PSP among inpatients in small and medium-sized hospitals, thereby increasing PP. Future research should focus on patient safety to further enhance the quality of medical services provided to inpatients in small and medium-sized hospitals. Efforts should be directed toward establishing a patient safety culture that actively involves both medical staff and patients, enabling effective education and interventions in clinical settings. Finally, it is necessary to develop various patient safety education plans in which inpatients can directly participate. Continuous support and management should be provided so that these plans can be systematically applied.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Sun-Hwa Shin has been a public relations director at the Korean Society of Adult Nursing since 2024–2025. She was not involved in the review process of this manuscript. She had no other conflicts of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and design acquisition - SHS; analysis - SHS and OJB; interpretation of the data - SHS; and drafting or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content - SHS and OJB.

-

FUNDING

This paper was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (NRF No. 2022R1F1A106447512).

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Thank you to all the patients who participated in the study.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data can be obtained from the corresponding authors.

Figure 1.The mediating effect of patient safety perception (PSP) in the relationship between right to know (RtK) and patient participation (PP). The solid lines indicate significant path coefficients. c=total effect; c’=direct effect.

Table 1.General Characteristics of Participants (N=231)

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

n (%) |

|

Sex |

Male |

81 (35.1) |

|

Female |

150 (64.9) |

|

Age (year) |

21–30 |

51 (22.1) |

|

31–40 |

114 (49.4) |

|

41–50 |

43 (18.6) |

|

≥51 |

23 (10.0) |

|

Education level |

High school |

41 (17.7) |

|

University |

190 (82.3) |

|

Occupation |

No |

35 (15.2) |

|

Yes |

196 (84.8) |

|

Marital status |

Married |

115 (49.8) |

|

Single |

116 (50.2) |

|

Underlying disease |

No |

161 (69.7) |

|

Yes |

70 (30.3) |

|

Frequency of hospital visits |

Once a month |

57 (24.7) |

|

Once every 3 months |

78 (33.8) |

|

Once every 6 months |

66 (28.5) |

|

At least once per year |

30 (13.0) |

|

Frequency of hospitalizations (times) |

2 |

107 (46.3) |

|

3 |

70 (30.3) |

|

≥4 |

54 (23.4) |

|

Patient safety incident |

No |

204 (88.3) |

|

Yes |

27 (11.7) |

|

Patient safety education |

No |

24 (10.4) |

|

Yes |

207 (89.6) |

Table 2.Differences in RtK, PSP, and PP by General Characteristics (N=231)

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

RtK |

PSP |

PP |

|

M±SD |

t/F(p) |

M±SD |

t/F(p) |

M±SD |

t/F(p) |

|

Sex |

Male |

3.75±0.43 |

–5.14 (<.001) |

4.21±0.38 |

–2.47 (.014) |

4.19±0.42 |

–3.83 (<.001) |

|

Female |

4.07±0.45 |

4.36±0.48 |

4.42±0.44 |

|

Age (year) |

21–30a

|

4.27±0.39 |

19.21 (<.001) |

4.52±0.42 |

6.81 (<.001) |

4.53±0.43 |

9.82 (<.001) |

|

31–40b

|

3.88±0.41 |

a>b>c |

4.28±0.43 |

a>b,c |

4.32±0.41 |

a>b>c |

|

41–50c

|

3.67±0.47 |

d>c |

4.13±0.42 |

|

4.07±0.42 |

d>c |

|

≥51d

|

4.15±0.42 |

|

4.29±0.55 |

|

4.46±0.47 |

|

|

Education level |

High school |

3.69±0.60 |

–3.36 (.002) |

4.23±0.52 |

–1.11 (.270) |

4.13±0.54 |

–2.85 (.006) |

|

University |

4.02±0.41 |

4.32±0.44 |

4.38±0.41 |

|

Occupation |

No |

4.13±0.45 |

2.34 (.020) |

4.31±0.50 |

0.07 (.946) |

4.38±0.46 |

0.70 (.485) |

|

Yes |

3.93±0.46 |

4.31±0.45 |

4.33±0.45 |

|

Marital status |

Married |

3.81±0.49 |

–5.21 (<.001) |

4.16±0.48 |

–4.95 (<.001) |

4.20±0.48 |

–4.88 (<.001) |

|

Single |

4.11±0.39 |

4.45±0.38 |

4.47±0.37 |

|

Underlying disease |

No |

3.98±0.51 |

1.48 (.140) |

4.35±0.46 |

2.43 (.016) |

4.39±0.46 |

2.76 (.006) |

|

Yes |

3.90±0.35 |

4.20±0.41 |

4.21±0.39 |

|

Frequency of hospital visits |

Once a montha

|

4.00±0.41 |

9.84 (<.001) |

4.35±0.49 |

5.80 (.001) |

4.43±0.46 |

6.98 (<.001) |

|

3 monthsb

|

3.94±0.42 |

d>a,b,c |

4.30±0.38 |

d>c |

4.31±0.39 |

a>c |

|

6 monthsc

|

3.78±0.50 |

|

4.16±0.44 |

|

4.18±0.43 |

d>b,c |

|

Once per yeard

|

4.30±0.42 |

|

4.56±0.48 |

|

4.58±0.47 |

|

|

Frequency of hospitalizations (times) |

2a

|

4.09±0.44 |

8.63 (<.001) |

4.46±0.47 |

13.52 (<.001) |

4.46±0.47 |

9.66 (<.001) |

|

3b

|

3.87±0.45 |

a>b,c |

4.23±0.35 |

a>b,c |

4.26±0.40 |

a>b,c |

|

≥4c

|

3.81±0.46 |

|

4.10±0.44 |

|

4.17±0.39 |

|

|

PS incident |

No |

3.96±0.46 |

0.24 (.807) |

4.34±0.44 |

3.25 (.001) |

4.35±0.44 |

1.47 (.144) |

|

Yes |

3.94±0.54 |

4.04±0.47 |

4.22±0.52 |

|

PS education |

No |

3.81±0.50 |

–1.69 (.091) |

4.03±0.51 |

–3.24 (.001) |

4.18±0.48 |

–1.82 (.070) |

|

Yes |

3.98±0.46 |

4.34±0.44 |

4.35±0.44 |

Table 3.Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of RtK, PSP, and PP (N=231)

|

Variables |

r (p) |

M±SD |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

|

PSP |

PP |

|

RtK |

.68 (<.001) |

.78 (<.001) |

3.96±0.47 |

–0.25 |

–0.67 |

|

PSP |

|

.83 (<.001) |

4.31±0.45 |

–0.35 |

0.18 |

|

PP |

|

|

4.33±0.45 |

–0.31 |

0.31 |

Table 4.Results of Mediating Effect Analysis (N=231)

|

Step |

DV |

IV |

B |

SE |

β |

t |

p

|

Adj. R2

|

F (p) |

|

1 |

PSP |

RtK |

0.62 |

0.06 |

.64 |

11.23 |

<.001 |

.516 |

21.24 (<.001) |

|

2 |

PP |

RtK |

0.70 |

0.05 |

.74 |

15.05 |

<.001 |

.642 |

35.79 (<.001) |

|

3 |

PP |

RtK |

0.35 |

0.04 |

.37 |

8.06 |

<.001 |

.802 |

73.38 (<.001) |

|

PSP |

0.56 |

0.04 |

.57 |

13.22 |

<.001 |

|

|

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization. Patient safety [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 [cited 2024 September 19]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/patient-safety

- 2. Shin HH, Jeong SH, Yoo JW. Survey on the status of patient safety activities in medical institutions and measures to revitalize typography safety activities. Seoul: Korean Institute of Hospital Management; 2015 September. Report No.: KIHM 2014-03.

- 3. Korea Patient Safety Reporting and Learning System. Statistics portal [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Patient Safety Report Learn System; 2024 [cited 2024 September 19]. Available from: https://statistics.kops.or.kr/biWorks/dashBoardMain.do

- 4. Lee SI. The meaning and task of patient safety law. Health Welf Policy Forum. 2016;240:2-4.

- 5. Park SH, Kwak MJ, Kim CG, Lee SI, Lee SG, Cho YK, et al. Necessity of introducing assistant staff to support administrative tasks related patient safety. Qual Improv Health Care. 2020;26(1):46-54. https://doi.org/10.14371/QIH.2020.26.1.46

- 6. Korea Institute for Healthcare Accreditation. Accredited organizations 2019. Seoul: Korea Institute for Healthcare Accreditation; 2020 [cited 2024 September 19]. Available from: https://www.koiha.or.kr/member/kr/certStatus/certList.do

- 7. Baek OJ, Shin SH. An importance-performance analysis of patient safety activities for inpatients in small and medium-sized hospitals. J Korean Acad Soc Nurs Educ. 2024;30(2):170-81. https://doi.org/10.5977/jkasne.2024.30.2.170

- 8. Moon S, Lee J. Correlates of patient safety performance among nurses from hospitals with less than 200 beds. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2017;29(4):393-405. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2017.29.4.393

- 9. Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O'Connor DB. Healthcare staff wellbeing, burnout, and patient safety: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159015

- 10. Amaral C, Sequeira C, Albacar-Rioboo N, Coelho J, Pinho LG, Ferre-Grau C. Patient safety training programs for health care professionals: a scoping review. J Patient Saf. 2023;19(1):48-58. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000001067

- 11. Kim J, Kim M. The impact of patient-centered care on the patient experience according to patients in a tertiary hospital. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2023;29(3):288-97. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2023.29.3.288

- 12. Kim AN, Park JS. Awareness of patient safety and performance of patient safety activities among hospitalized patients. J Korea Acad Ind Coop Soc. 2021;22(5):229-40. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2021.22.5.229

- 13. Kim KJ, Lee EH, Shin SH. Development and validation of the patient safety perception scale for hospitalized patients. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2018;30(4):404-16. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2018.30.4.404

- 14. Kang SJ, Park JY. Patient safety perception and patient participation among hemato-oncology patients. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2019;19(4):224-32. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2019.19.4.224

- 15. Won MH, Shin SH. Mediating effects of patient safety perception and willingness to participate in patient safety on the relationship between health literacy and patient participation behavior among inpatients. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1349891. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1349891

- 16. Kim JH, Lee JL, Kim EM. Patient safety culture and handoff evaluation of nurses in small and medium-sized hospitals. Int J Nurs Sci. 2021;8(1):58-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnss.2020.12.007

- 17. World Health Organization. People-centered health care: a policy framework. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

- 18. Song M, Kim M. Development and validation of a patient participation scale. J Adv Nurs. 2023;79(6):2393-403. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15593

- 19. Berger Z, Flickinger TE, Pfoh E, Martinez KA, Dy SM. Promoting engagement by patients and families to reduce adverse events in acute care settings: a systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(7):548-55. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-001769

- 20. Cai Y, Liu Y, Wang C, Liu S, Zhang M, Jiang Y. Patient and family engagement interventions for hospitalized patient safety: a scoping review. J Clin Nurs. 2024;33(6):2099-111. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.17022

- 21. Lee M, Lee NJ, Seo HJ, Jang H, Kim SM. Interventions to engage patients and families in patient safety: a systematic review. West J Nurs Res. 2021;43(10):972-83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945920980770

- 22. Ahn SH, Kim YS, Yoo MS, Bang KS. A patient’s right to know and self-determination. Korean J Med Ethics. 2009;12(2):153-64. https://doi.org/10.35301/ksme.2009.12.2.153

- 23. Do YK, Kim JY, Lee JY, Lee HY, Cho MO. Research on the development of patient-centered evaluation model. Wonju: Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service; 2015. Report No.: G000E70-2015-87.

- 24. Lee YH, Lee JH. Effects of awareness of guarantee of medical service right and satisfaction of consumer competency on satisfaction of medical service. J Consum Policy Stud. 2014;45(3):81-111. http://doi.org/10.15723/jcps.45.3.201412.81

- 25. Lee H. Healthcare service consumer’s perception of patient safety: relationship between perception of patient safety, right to know and self-determination [master’s thesis]. Seoul: Yonsei University; 2016.

- 26. Baek OJ, Shin SH. The moderating effect of patient safety knowledge in the relationship between patient experience and patient safety perception for patients in primary care institutions. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2021;33(4):387-98. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2021.33.4.387

- 27. Shin SH. A convergence study on the relationship among patient safety activity experience, patient safety perception and willingness to participate in the general population. J Korea Converg Soc. 2020;11(9):405-15. https://doi.org/10.15207/JKCS.2020.11.9.405

- 28. Choi HJ, Lee E. The effects of smartphone application to educate patient on patient safety in hospitalized surgical patients. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2017;29(2):154-65. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2017.29.2.154

- 29. Giles SJ, Lawton RJ, Din I, McEachan RR. Developing a patient measure of safety (PMOS). BMJ Qual Saf. 2013;22(7):554-62. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000843

- 30. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2018.

- 31. Forsyth R, Maddock CA, Iedema RA, Lassere M. Patient perceptions of carrying their own health information: approaches towards responsibility and playing an active role in their own health - implications for a patient-held health file. Health Expect. 2010;13(4):416-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2010.00593.x

- 32. Chung S, Hwang JI. Patients’ experience of participation in hospital care. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2018;23(5):504-14. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2017.23.5.504

- 33. Joe S, Kim JH. The effects of patient participation education on the patient safety perception, patient participation, and patient-provider relationship in ROK military hospital. Korean J Mil Nurs Res. 2022;40(2):21-34. https://doi.org/10.31148/kjmnr.2022.40.2.21

- 34. Hardy LR. Using big data to accelerate evidence-based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2018;15(2):85-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12279