Abstract

-

Purpose

This study aimed to suggest directions for legislation regarding medical support tasks in the Nursing Act to promote the advancement of nursing.

-

Methods

This study reviewed the history of medical support nurses in South Korea and the educational programs for advanced practice providers, both domestically and internationally.

-

Results

Nurses have performed medical support tasks traditionally carried out by physicians, but legal controversies have persisted. As a result of the escalation of conflicts surrounding policies aiming to increase the physician workforce, training doctors left hospitals. This prompted the initiation of pilot programs allowing nurses to legally engage in medical support tasks, culminating in the enactment of the Nursing Act in September 2024. Internationally, advanced practice providers such as advanced practice nurses (APNs) and physician assistants (PAs) undergo graduate-level education and certification. Since Korea lacks a PA system, integrating medical support tasks within the APN framework would be preferable. Achieving this will require absorbing clinical practice nurses (referred to as PA nurses) into the APN system, implementing government-supported education programs to address regional disparities, and establishing reimbursement policies for APNs.

-

Conclusion

With the implementation of the Nursing Act, a long-term approach is needed to establish professional qualifications, accreditation, education, training, examination, and regulatory systems. A comprehensive discussion should be undertaken to develop an optimal workforce, ensuring the delivery of safe and high-quality healthcare services to patients and the public.

-

Key Words: Advanced practice nursing; Legislation, nursing; Professionalism; Role

INTRODUCTION

The Korean medical community experienced a tumultuous year in 2024. In early February, government plans to increase the medical school admissions quota met with unprecedented opposition, as 91.5% of interns and residents (12,380 individuals) left hospitals, and medical students refused classes. This healthcare gap was partly filled by nurses and advanced practice nurses (APNs) through a “pilot project on nursing-related tasks” [

1]. Amid ongoing conflicts between the medical community and the government, the scope of nursing duties was expanded in September 2024 with the promulgation of the Nursing Act, which now authorizes APNs and qualified nurses to perform medical support tasks [

2]. Although this decision emerged amidst a crisis, it marked a turning point in which the long-undervalued professionalism of nursing personnel began receiving formal recognition by both the government and the healthcare industry.

Following the legislative announcement of enforcement decrees and rules, which include detailed implementation plans reflecting opinions from the healthcare community and civic groups, the Nursing Act is scheduled to take effect on June 21, 2025, after a period of public consultation. While some predict that the pilot project on nursing-related tasks implemented in 2024 will ease consensus on medical support tasks, substantial disagreements remain regarding the specific duties and qualifications required for nurses performing these tasks. Therefore, we intend to examine domestic and international practices of medical support tasks and propose directions for their legalization in the Nursing Act to facilitate the advancement of nursing.

THE INITIATION AND EXPANSION OF MEDICAL SUPPORT TASKS AMONG NURSES IN SOUTH KOREA

Korean nurses have performed medical support tasks since the 1970s, prior to the establishment of nationwide universal healthcare, when basic primary care was delivered in rural, physician-scarce areas through public health clinics staffed by nurses [

3]. Legislation such as the Rural Special Acts enabled nurses to provide primary care, preventive programs, and health education. Moreover, provisions in the School Health Act, Industrial Safety and Health Act, and Correctional Services Act authorized nurses to treat patients, administer emergency care, and dispense medications during periods or in areas when physicians were unavailable.

Since the introduction of the National Health Insurance System in 1989, physician shortages in medical institutions have become a concern [

4]. Increased demand for medical services under expanded insurance coverage led to a significant rise in hospital beds, yet the number of doctors did not increase proportionately. This discrepancy was further aggravated by the enforcement of the separation of medicine and pharmacy in 2000, which reduced medical school admission quotas by 10%, and by the reduction of residents’ and interns’ working hours under a 2017 regulation aimed at improving training conditions and status [

4]. Additionally, physicians increasingly preferred more lucrative specialties, such as cosmetic and plastic surgery (which are not covered by insurance), over essential services like emergency departments and intensive care units, thereby deepening existing healthcare disparities.

In Korean medical law, medical practice is defined as an exclusive responsibility of physicians [

5]; yet, in reality, doctors cannot manage all their extensive duties alone. In many healthcare institutions, nurses with various designations, such as APNs, clinical practice nurses, coordinators, and physician assistant (PA) nurses, perform tasks including prescription writing, documentation, and other clinical activities under the delegation of physicians, often using the physician’s identification. This practice has repeatedly sparked legal disputes [

6,

7]. Moreover, even APNs who meet the qualifications specified by medical law are confined by the scope defined by their nursing licenses [

8]. Additionally, nurses referred to as PAs, who are not legally recognized in South Korean medical law, have been embroiled in legal controversies over unauthorized medical practices, resulting in lawsuits [

7].

In early 2024, most residents and interns who opposed the government’s plan to expand medical school enrollment quotas left hospitals. This departure prompted the initiation of a temporary “pilot project on nursing-related tasks” [

1], enabling nurses to perform medical support tasks. In September of that year, the scope of nursing duties was further expanded through legislation to officially include medical support tasks [

2]. Furthermore, starting in October, the Tertiary General Hospital Transformation Support Project proposed replacing the conventional, resident- and intern-centered on-call system with a model led by experienced teams composed of specialists and medical support nurses. This shift aims to concentrate on care for severe, emergency, and rare diseases while ensuring high-quality training for interns and residents.

If the government envisions medical support task nurses as essential team members alongside specialists, it becomes crucial to review the training and qualifications of their counterparts abroad and integrate these standards into the domestic Nursing Act’s enforcement rules. The Nursing Act is scheduled to take effect on June 21, 2025; however, in accordance with Article 14, Paragraph 2, the designation and evaluation of institutions that conduct educational programs must be implemented within three years from nine months after its promulgation [

2]. Establishing a robust education system is imperative to ensure patient safety, broaden the scope of nursing, and strengthen professional expertise. Consequently, we intend to review international educational practices and discuss improvements for educating domestic medical support task nurses.

PROPOSED FRAMEWORK FOR DOMESTIC EDUCATION FOR NURSES ON MEDICAL SUPPORT TASKS BASED ON THE INTERNATIONAL SYSTEM FOR ADVANCED PRACTICE PROVIDER EDUCATION

The global shortage of physicians has driven many countries to train non-physician clinicians—such as APNs and PAs—and to expand their scope of practice [

9–

12]. These non-physician clinicians are often referred to as middle-level providers or advanced practice providers (APPs). In countries with a high utilization rate of APPs, education and certification systems have been established to ensure that these professionals acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to safeguard public health and safety [

7,

13]. Although APNs originate from a nursing background, PAs can be recruited from non-medical fields; consequently, PA programs typically require more extensive education and practical training hours in their master’s curricula than those for APNs [

11,

13]. Since South Korea does not have a PA system, it is more appropriate to rely on APNs, and hence, we will focus on examining the APNs education system.

In both Singapore and Taiwan—where the APN system emerged around the same time as in South Korea—governments reviewed qualifications for APP personnel and ultimately recognized only APNs, excluding PAs [

14,

15]. In Singapore, APNs candidates must complete a master’s degree program that lasts 1 year and 6 months, followed by a mandatory 1-year internship under an accredited preceptor, which includes at least 1,280 hours of clinical practice. Additionally, candidates are required to submit a specified number of Objective Structured Clinical Examination reports based on direct patient examinations [

15]. In Taiwan, eligibility for the APN examination can be achieved either by completing a master’s degree program for APNs or by completing 1,500 hours of clinical training as part of a team consisting of one specialist with at least two years of experience and four APNs, along with a minimum of 213 hours of theoretical education at an educational hospital with a dedicated department for APNs [

16]. In both the United States and the United Kingdom, APN programs require a minimum of 500 hours of clinical practice [

12].

In countries where the roles of APNs have been expanded, educational curricula require significantly more practical training than those in Korea. Given that the Nursing Act is expected to broaden the scope of medical support tasks beyond what is outlined in current medical laws, revising the existing APN curriculum is inevitable. APNs may be expected to perform more invasive procedures and manage delegated prescriptions for diverse patient needs. In some hospitals participating in the Tertiary General Hospital Transformation Support Project, APNs work 24/7 shifts, respond to primary patient calls, and resolve issues based on their own judgment whenever possible. In certain institutions, APNs share inpatient management duties with physicians. This model of shift-based APN work was proposed even before the current conflicts between medical and governmental entities, when hospitalists were encouraged to collaborate in teams with APNs [

17]. Consequently, to enable APNs to fully assume their roles as competent APPs, they must further develop their skills in health assessment, technical procedures, and clinical reasoning. Their training should comprehensively cover essential subjects—such as pathophysiology, pharmacology, physical/health examination, and health promotion, which constitute the “4Ps” of education [

18]—and both the academic curriculum and clinical practice components must be realigned with evolving clinical demands. Educational programs should be a collaborative effort between academic institutions and the healthcare settings where the nurses will work. Moreover, it is necessary to explore the possibility of integrating current clinical practice nurses engaged in medical support tasks into the formal APN system.

FUTURE CHALLENGES FOR UTILIZING ADVANCED PRACTICE NURSES AS ADVANCED PRACTICE PROVIDERS

APNs have achieved significant success in enhancing patient outcomes and satisfaction, and they are now employed globally [

19]. Their effectiveness likely stems from a holistic approach to patient care, deeply embedded in nursing principles. According to the U.S. Department of Labor’s projections, while the number of physicians is expected to increase by only 2.9% between 2021 and 2031, the number of APNs is projected to rise by 45.7%, highlighting the growing demand for these professionals [

11]. In Korea, patients who have been cared for by APNs frequently describe them as “experts with specialized knowledge and diverse clinical experience,” “facilitators who help patients manage their conditions independently,” and “indispensable healthcare professionals who bridge the gap between doctors and patients” [

20].

Nevertheless, due to the vague boundaries of APNs’ responsibilities and inadequate fee-for-service and compensation structures, many medical institutions continue to assign medical support tasks to nurses under the designation of PA nurses—a title not recognized by medical law—instead of fully utilizing APNs [

21]. Consequently, to ensure the active deployment of well-trained APNs, several issues require resolution. These include: “What should be done with clinical practice nurses already performing medical support tasks?”, “Is there a sufficient number of APNs capable of undertaking these roles?”, “Are there enough educational institutions to train APNs, particularly in rural areas where educational disparities are more pronounced?”, and “Is the APN system economically sustainable?” In this paper, we present opinions addressing these questions.

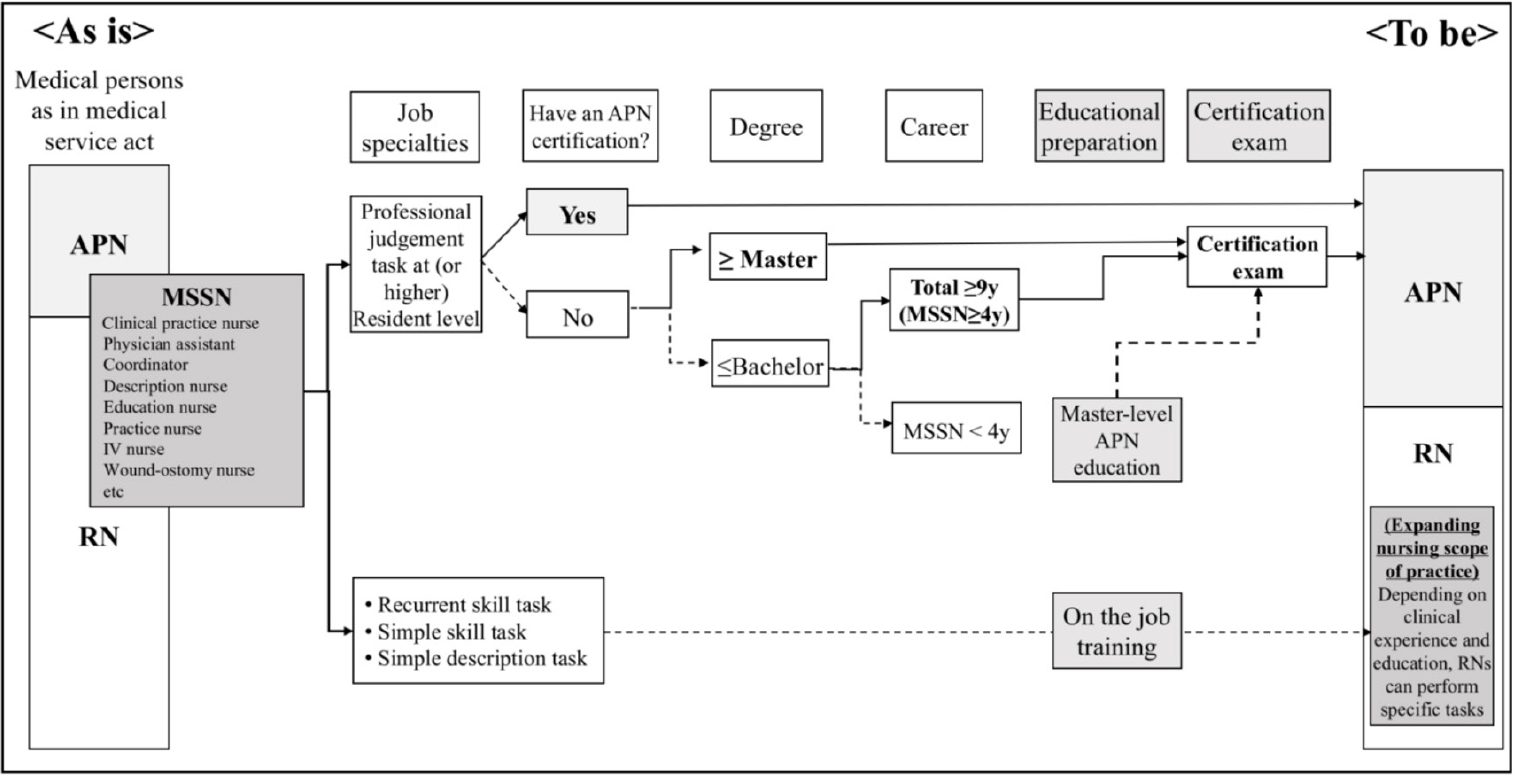

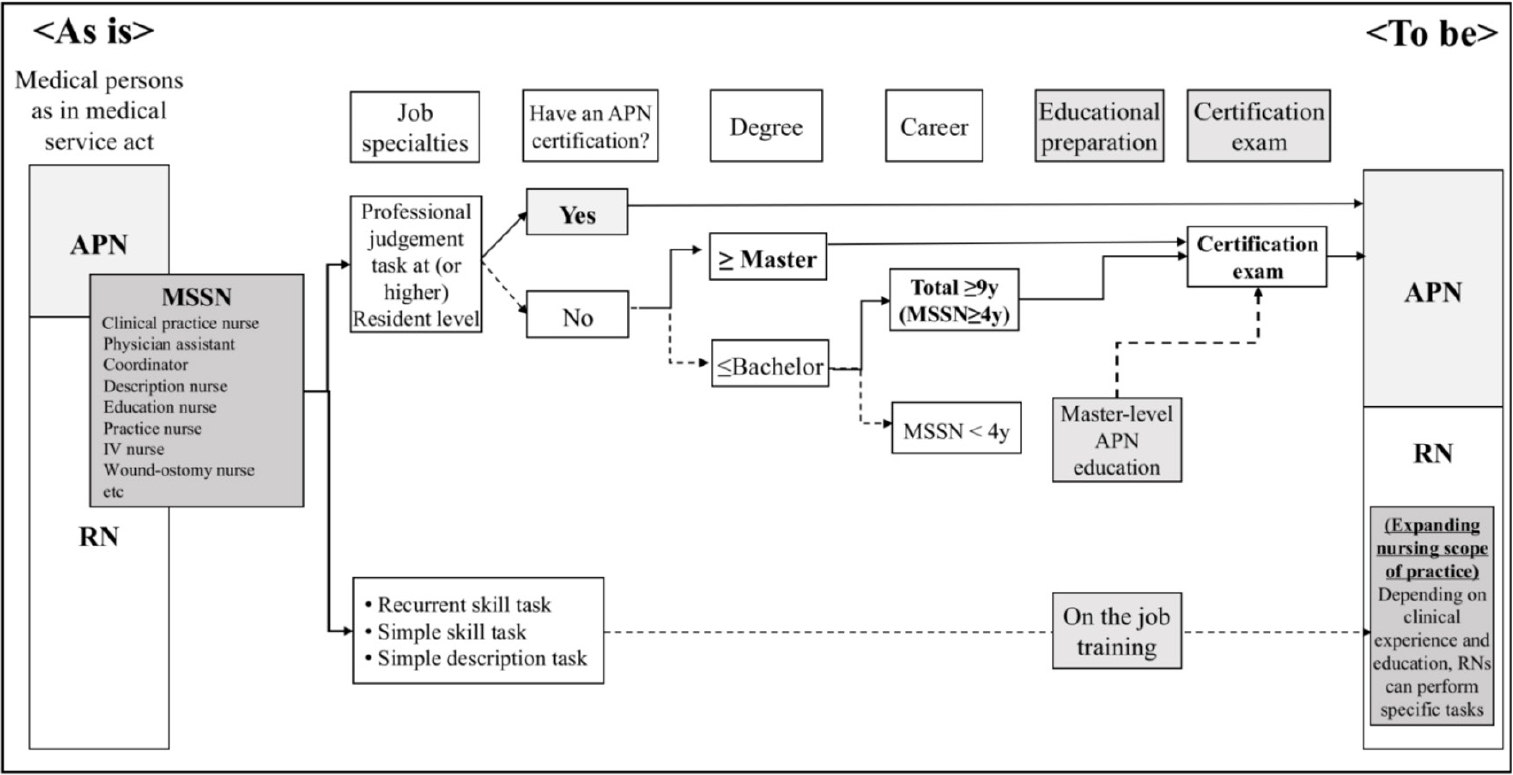

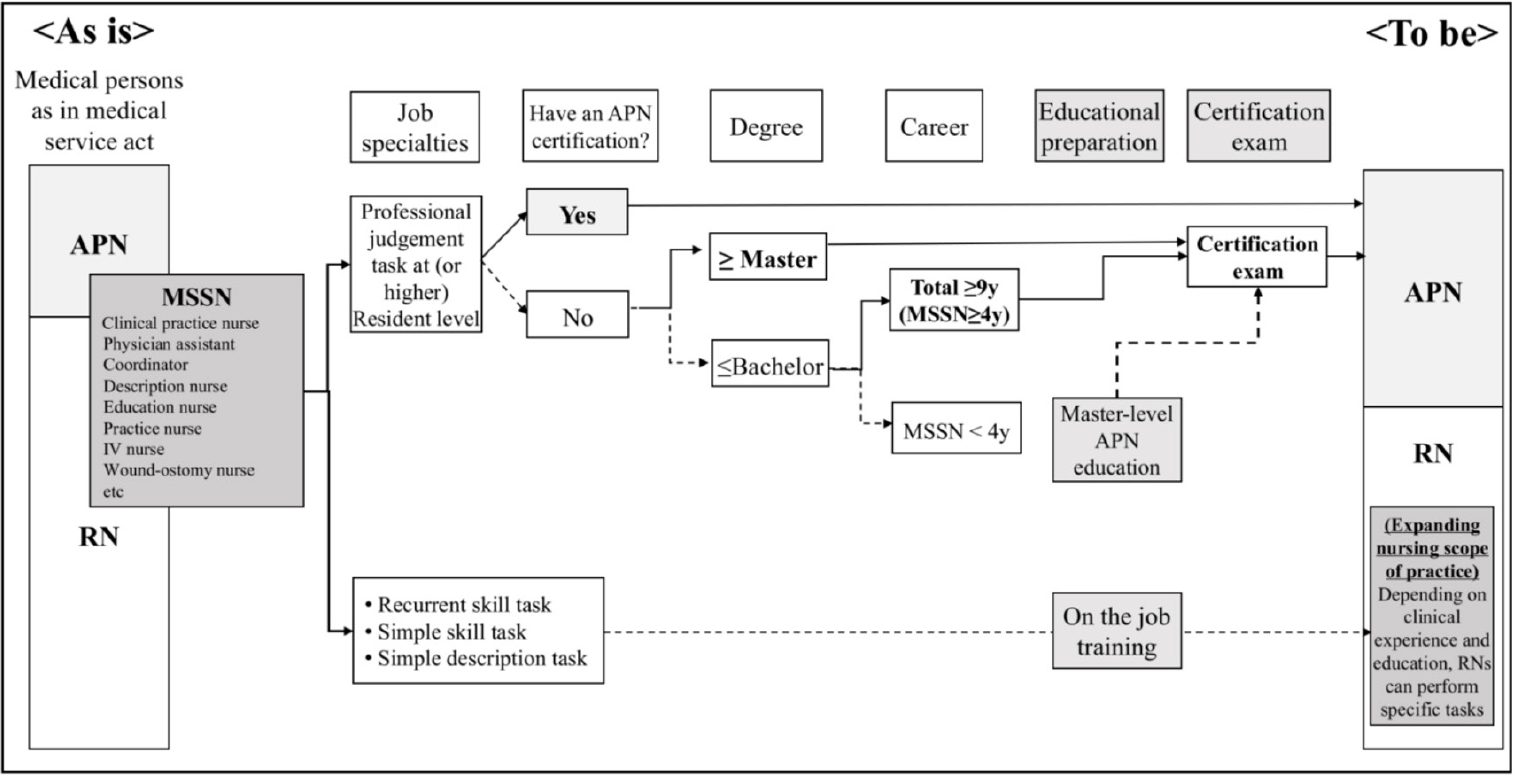

First, we address solutions concerning existing clinical practice nurses. Although 17,850 nurses are currently certified as APNs, the absence of a reporting system obscures their actual activities within healthcare institutions. A study [

22] surveying 1,347 certified APNs found that 29.1% were working as APNs, 14.5% as clinical practice nurses, 30.0% as registered nurses, and 24.1% in academic or managerial roles—indicating that many certified individuals do not serve as APNs. While three major tertiary hospitals in Seoul report having between 100 and 200 APNs in practice, most other healthcare facilities either have few or no positions designated for APNs. Notably, a study conducted in institutions that operate solely under the clinical practice nurse model [

23] reported that 34.3% of clinical practice nurses held APN certifications. Therefore, nurses holding APN certification should be formally assigned to APN roles. Additionally, individuals with master’s degrees or substantial clinical practice nurses experience—those capable of performing as APPs—should be granted opportunities to sit for the APN certification exam via an exceptional process [

6]. Although societal consensus on such exceptions is necessary, temporary measures might be justified. For instance, if clinical practice nurses experience is deemed equivalent to a residency training program—as demonstrated by Taiwan’s APN certification process [

16]—then temporary exceptions could be implemented. (refer to

Figure 1 for an example of such an exceptional process.)

Second, we address the issue of insufficient educational institutions for APNs. Currently, 39 institutions run APN programs, but these are largely concentrated in major metropolitan areas [

24]. APN curricula require more coursework and clinical practice hours compared to existing master’s programs in nursing, which places considerable strain on faculty and results in high tuition fees for students. To alleviate regional disparities in education, local governments should support the establishment of additional training institutions—for example, by promoting APN education in rural areas through a contract education system. Under such a system, businesses would request schools to offer training programs, provide tuition support for students, and offer financial aid to educational institutions, with the condition that graduates work for the sponsoring business for a set period [

25]. By having local governments support this system and universities manage APN programs as contract-based departments, regional disparities in educational opportunities can be reduced, and healthcare facilities will be better positioned to employ experienced nurses. Moreover, once certified, APNs not only represent experienced healthcare personnel but also have the potential to expand their roles as APPs collaborating with physicians. This approach—integrating existing clinical practice nurses into APN roles and expanding regional education—could significantly increase the supply of APNs.

Finally, for the role and system of APNs to expand, institutional support is required—not only through legalizing their scope of practice and activating reimbursement systems, but also by ensuring that institutions employing APNs provide support for efficient job performance, including the development of detailed job descriptions. On an individual level, APNs must continuously update their knowledge of current trends and engage in ongoing research to demonstrate their effectiveness (

Table 1). Proving their cost-effectiveness is crucial for justifying reimbursement and for gaining recognition for their expertise. For example, in South Korea, the additional deployment of specialized nursing personnel in intensive care units has been shown to increase sepsis bundle intervention rates, ultimately reducing patient mortality [

26]. This success has paved the way for pilot projects such as rapid response teams that include additional staffing reimbursements. Although pioneering a new role presents challenges, failure to establish and publicize the role may cause it to remain confined to a supplementary position in clinical practice. Therefore, APNs must actively engage in research, promote their roles, and demonstrate leadership.

CONCLUSION

Expanding the scope of APNs as APPs is likely to have a substantially positive impact on public health rather than causing harm [

27]. As the responsibilities of both registered nurses and APNs evolve, academic institutions and clinical facilities must collaborate to provide multidisciplinary education and training to ensure that patients receive optimal care. In the future, as legal recognition of nurses’ roles in medical support tasks increases along with the contributions of skilled APNs, improved patient outcomes and enhanced medical services are expected to be increasingly documented. Naturally, this should lead to appropriate compensation. Although current discussions about APNs are predominantly focused on healthcare institution-based settings—due to ongoing conflicts between the medical community and the government—future dialogues should also explore the diverse roles that APNs can play in community-based settings. For example, employing APNs in schools (in addition to public health nurses) or in nursing homes could help address local healthcare challenges.

The establishment of the Nursing Act, along with changes in the healthcare system, will necessitate adaptations in the roles and responsibilities of medical personnel. New qualifications, authority, and accountability for performing these duties will be required. From a long-term perspective, it is essential to engage in a comprehensive dialogue on strategies to cultivate and deploy optimal healthcare personnel. This will involve addressing licensing, certification, accreditation, education, training, examinations, and regulatory measures to ensure the provision of safe and superior medical services to both patients and the public.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declared no conflict of interest.

-

FUNDING

None.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

None.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

No new data were created or analyzed during this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Figure 1.Credentials and special qualification acceptance criteria. This figure has been reproduced with permission from the

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2024;54(3):300-10 [

6]. APN=advanced practice nurse; MSSN=medical support staff nurse; RN=registered nurse.

Table 1.Strategies for Facilitating the Role of Advanced Practice Nurses in Korea

|

Level |

Strategies |

|

Macro (structural) level (government) |

Legislate and extend the scope of practice |

|

Remuneration |

|

Remodeling and integration of the 13 APN specialties |

|

Meso level (institution) |

Foster APN (position & reward) |

|

Privileges (competency-based job description) |

|

Micro level (individual) |

Continued clinical competency |

|

Research and evidence-based practice |

|

Leadership competency |

REFERENCES

- 1. Division of Nursing Policy. Pilot project related to nurse scope of work [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2024 [cited 2024 May 2]. Available from: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10504000000&bid=0030&cg_code=

- 2. Nursing Acts [Internet]. Sejong: Korean Law Information Center; 2024 [cited 2025 March 20]. Available from: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/lsInfoP.do?lsiSeq=265413&viewCls=lsRvs-DocInfoR#

- 3. Seol M, Shin YA, Lim KC, Leem C, Choi JH, Jeong JS. Current status and vitalizing strategies of advanced practice nurses in Korea. Perspect Nurs Sci. 2017;14(1):37-44. https://doi.org/10.16952/pns.2017.14.1.37

- 4. Choi SJ, Kim YH, Lim KC, Kang YA. Advanced practice nurse in South Korea and current issues. J Nurse Pract. 2023;19(9):104486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nurpra.2022.10.015

- 5. Medical Service Act [Internet]. Sejong: Korean Law Information Center; 2020 [cited 2025 March 20]. Available from: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/eng/engLsSc.do?menu=2&query¼MEDICAL%20SERVICE%20ACT#liBgcolor30

- 6. Choi SJ, Kim MY. Legal and practical solutions for the expanding the roles of medical support staff nurses. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2024;54(3):300-10. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.24075

- 7. Yum HK, Lim CH, Park JY. Medicosocial conflict and crisis due to illegal physician assistant system in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(27):e199. https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2021.36.e199

- 8. Kim HN, Kim KH. Legal review on physician assistants. Chonnam Law Rev. 2016;36(3):331-52.

- 9. Maier CB, Aiken LH. Task shifting from physicians to nurses in primary care in 39 countries: a cross-country comparative study. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(6):927-34. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw098

- 10. Dankers-de Mari E, van Vught A, Visee HC, Laurant MG, Batenburg R, Jeurissen PP. The influence of government policies on the nurse practitioner and physician assistant workforce in the Netherlands, 2000-2022: a multimethod approach study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):580. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09568-4

- 11. Hooker RS, Christian RL. The changing employment of physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician associates/assistants. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2023;35(8):487-93. https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000917

- 12. Wheeler KJ, Miller M, Pulcini J, Gray D, Ladd E, Rayens MK. Advanced practice nursing roles, regulation, education, and practice: a global study. Ann Glob Health. 2022;88(1):42. https://doi.org/10.5334/aogh.3698

- 13. Yoon SJ. A review and implication of international trends for the definition and scope of physician assistant. Glob Soc Secur Rev. 2022;20:5-16. https://doi.org/10.23063/2022.03.1

- 14. Chou LP, Hu SC. Physician assistants in Taiwan. J Am Acad Physician Assist. 2015;28(3):1-3. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JAA.0000460932.03971.e0

- 15. Xu C, Koh KW, Zhou W. The development of advanced practice nurses in Singapore. Int Nurs Rev. 2024;71(2):238-43. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12810

- 16. Taiwan Association of Nurse Practitioners. Nurse Practitioners Laws [Internet]. New Taipei City: Taiwan Association of Nurse Practitioners; 2024 [cited 2025 March 20]. Available from: https://www.tnpa.org.tw/en/certification/nurse.php

- 17. Shin DH. The vision of hospitalist system in Korea. Korean J Med. 2021;96(1):1-6. https://doi.org/10.3904/kjm.2021.96.1.1

- 18. Day K, Hagler DA. Integrating the 4Ps in masters-level nursing education. J Prof Nurs. 2024;53:16-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2024.04.003

- 19. Kilpatrick K, Savard I, Audet LA, Costanzo G, Khan M, Atallah R, et al. A global perspective of advanced practice nursing research: a review of systematic reviews. PLoS One. 2024;19(7):e0305008. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0305008

- 20. Jeon MK, Choi SJ, Han JE, Kwon EK, Park JH, Kim JH. Experiences of patients and their families receiving medical services provided by advanced practice nurses at tertiary general hospitals. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2024;54(4):594-606. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.24069

- 21. Choi SJ, Lee DH, Kang YA, Lee CS, Jeon MK. A study of the roles, practice, and reimbursement of Korean advanced practice nurses, and proposal for improving reimbursement policies. J Korean Clin Nurs Res. 2024;30(3):178-92. https://doi.org/10.22650/JKCNR.2024.30.3.178

- 22. Shin YS, Yoon KJ, Chae SM, Kang YM, Kwon YJ, Jun A, et al. Research to revitalize the advanced practice nurse system. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2019.

- 23. Ryu MJ, Park M, Shim J, Lee E, Yeom I, Seo YM. Expectation of medical personnel for the roles of the physician assistants in a university hospital. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2022;28(1):31-42. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2022.28.1.31

- 24. Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing Education. Operation guideline of the advanced practice nurses' training course [Internet]. Seoul: Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing Education; 2025 [cited 2025 March 20]. Available from: http://www.kabone.or.kr/mainbusin/nurse03perform.do

- 25. Regulations on the establishment and operation of contracts [Internet]. Sejong: Korean Law Information Center; 2023 [cited 2025 April 1]. Available from: https://www.law.go.kr/LSW/admRulLsInfoP.do?chrClsCd=&admRulSeq=2100000223592#AJAX

- 26. Choi S, Son J, Oh DK, Huh JW, Lim CM, Hong SB. Rapid response system improves sepsis bundle compliances and survival in hospital wards for 10 years. J Clin Med. 2021;10(18):4244. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10184244

- 27. Markowitz S, Adams EK, Lewitt MJ, Dunlop AL. Competitive effects of scope of practice restrictions: public health or public harm? J Health Econ. 2017;55:201-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.07.004