Abstract

-

Purpose

This study involved a meta-synthesis of qualitative research concerning the experiences of women with infertility and infertility treatments. Based on an analysis of emotional changes and adaptation processes, it aimed to propose an interaction model encompassing expectation, loss, and resilience and clarify the conceptual meaning of each component.

-

Methods

Thomas and Harden’s five-step qualitative meta-synthesis methodology was employed. A total of 22 studies published between 2014 and 2024 were comprehensively analyzed and synthesized. The findings were integrated into a model representing the experiences of women undergoing infertility and infertility treatments.

-

Results

The meta-synthesis identified six key themes: changes in identity and inner growth; strengthening resilience through the roles of spouses, family, and peers; strategies for recovery and growth; support systems amidst economic and social burdens; life in the tension of waiting and hope; and the reconfiguration of couple and family relationships. Based on these themes, a dynamic interaction model, named the Model of Psychological Changes and Resilience (PCR Model), was developed to illustrate the interrelationships among expectation, loss, and resilience. The conceptual implications of these relationships were also explicated.

-

Conclusion

The cyclical interplay between expectation and loss among women experiencing infertility is intensified by social ideologies and cultural contexts, while resilience is strengthened through overcoming distress and finding meaning in life. Further quantitative research is necessary to validate these relationships in clinical settings by obtaining empirical data that apply this model.

-

Key Words: Female infertility; Hope; Grief; Psychological resilience; Psychological models

INTRODUCTION

The number of infertility patients in South Korea increased by 25.7% over the past decade, rising from 189,879 in 2012 to 238,610 in 2022 [

1]. Women accounted for 64% (152,953) of these cases. This trend aligns with global patterns but is particularly pronounced in Korea, influenced by sociocultural pressures and delayed childbearing. As of 2023, the average maternal age reached 33.6 years, with the proportion of mothers aged 35 and older rising from 19.7% in 2012 to 36.3% [

2]. Given the marked decline in fertility and

in vitro fertilization success rates after age 35 [

3], the physical, psychological, and financial burdens of treatment continue to increase. Women experiencing infertility often begin treatment filled with hope [

4], but repeated treatment failures lead to emotional exhaustion and psychological distress [

5]. While successful outcomes depend on age, health status, and treatment methods [

6], medical efforts alone cannot guarantee success, making emotional support essential [

7-

9]. This study adopts the term “women experiencing infertility” to reflect a person-centered and respectful perspective. Infertility is more than a medical condition; it involves navigating emotional, relational, and cultural challenges. Qualitative studies have identified core themes such as emotional distress, stigma, identity shifts, and disrupted relationships. However, differences in scope and methodologies among studies limit a comprehensive understanding. Thus, a meta-synthesis is needed to integrate these findings, reveal broader patterns, and deepen insight into how women psychologically adapt over time [

10].

Central to the infertility experience are psychological distress, bodily changes, relational shifts, and societal expectations. These factors shape how infertility is experienced and interpreted. Emotional distress arises from uncertainty and recurrent loss; bodily changes from treatment procedures affect self-image; relational tensions develop within partnerships and families; and societal ideals of motherhood amplify feelings of inadequacy. Together, these elements shape how women construct meaning and develop coping mechanisms.

This study examined how women progress through a psychological process involving expectation, loss, and resilience. These three components are interconnected, forming a cyclical pattern throughout infertility treatment. By synthesizing existing qualitative research, this study aims to construct an integrated model that represents these dynamic emotional transitions. The model has practical implications for clinical and policy settings. Clinically, it can guide tailored psychological support at each stage of infertility treatment. In terms of policy, the model highlights the need for stage-specific mental health services and public education that recognizes the long-term emotional impacts of infertility. Therefore, this model aims to contribute to more empathetic and comprehensive care.

The purpose of this study was to perform a meta-synthesis of primary qualitative research exploring the experiences of women undergoing infertility and infertility treatments. Specifically, the study aimed to analyze the emotional changes and adaptation processes of women experiencing infertility and to propose an interaction model involving expectation, loss, and resilience. Through this, the study sought to explain the conceptual meaning of each element.

METHODS

1. Research Design

This study is a qualitative meta-synthesis examining research on the experiences of women undergoing infertility and infertility treatments. Its objective was to explore psychological changes in an integrated manner and coping processes observed within infertility experiences. To achieve this, the study applies the thematic synthesis approach within qualitative meta-synthesis, involving five structured stages. This study adhered to the SWiM (Synthesis Without Meta-analysis) reporting guideline to ensure transparent and systematic reporting of the narrative synthesis.

2. Quality Assessment of Selected Literature

This study employed the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Qualitative Checklist to assess the quality of the selected literature [

11]. The CASP tool comprises 10 items evaluating the rigor and transparency of qualitative research, including clarity of research aims, appropriateness of methodology, recruitment strategy, data collection methods, ethical considerations, rigor in data analysis, and the value of findings. Each study was independently evaluated by two reviewers using a standardized scoring form, assigning scores as “yes” (1 point), “unclear” (0.5 points), or “no” (0 points) per item. The final score was calculated as a percentage of the total possible points. Only studies achieving a CASP compliance rate of 85% or higher were included to ensure methodological robustness (

Table 1). Discrepancies between reviewers’ scores were resolved through discussion and consensus, enhancing reliability and minimizing reviewer bias.

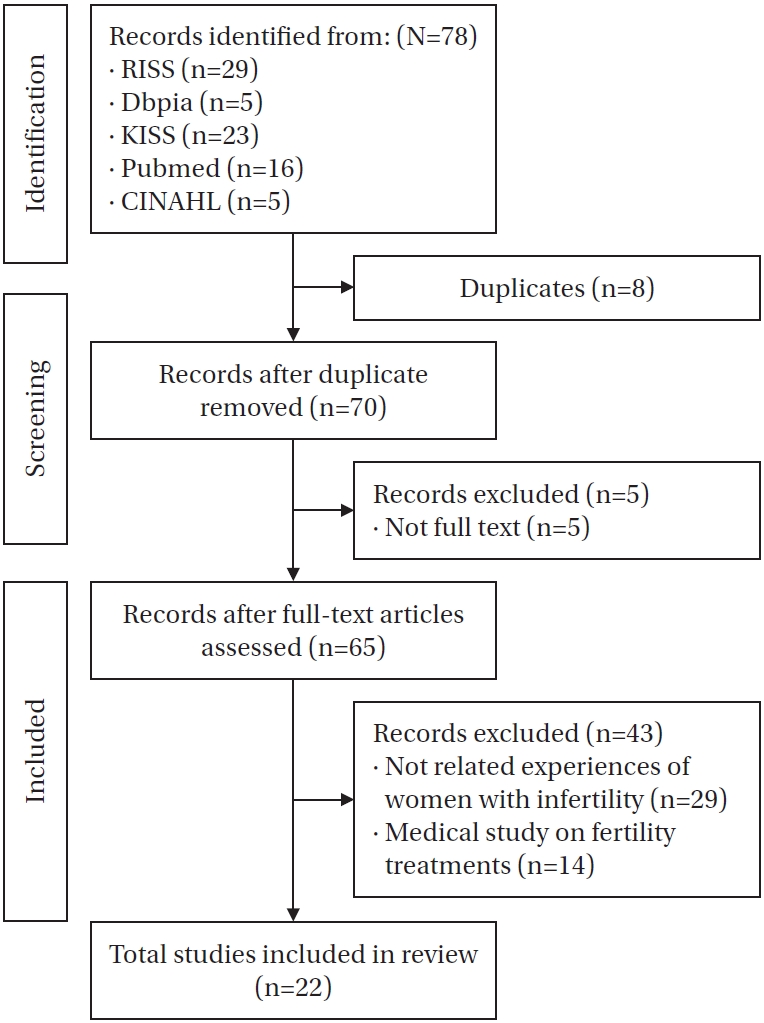

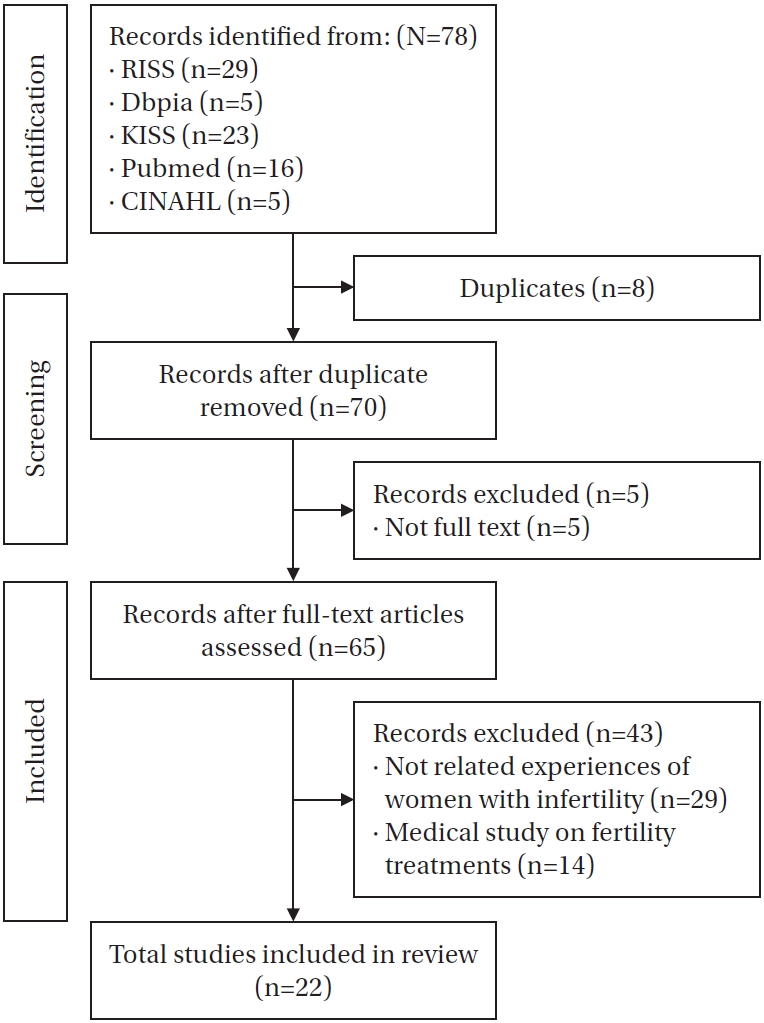

Qualitative studies on the experiences of women undergoing infertility and infertility treatments were identified through a comprehensive literature search, including articles published up to December 2024. The search was conducted across five major electronic databases: RISS, DBpia, KISS, PubMed, and CINAHL. Search terms included combinations of keywords such as “infertility,” “women,” “experience,” and “qualitative research,” tailored specifically for each database using Boolean operators (“AND,” “OR,” and “NOT”). To ensure completeness, additional manual searches were performed using relevant keywords on Google Scholar. A total of 78 articles were initially retrieved. All records were imported into EndNote for systematic management and removal of duplicates, resulting in the exclusion of eight duplicates, leaving 70 unique studies. In the second stage, five studies were excluded due to the unavailability of full texts, yielding 65 studies eligible for full-text review.

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies focused on women with infertility; (2) qualitative research addressing infertility experiences; and (3) publications available in Korean or English.

The exclusion criteria included: (1) studies primarily focusing on medical treatments rather than lived experiences; (2) policy- or project-related studies; (3) studies without full-text access, including conference abstracts and proceedings; and (4) non-peer-reviewed articles.

To ensure clarity, an operational definition of “lived experience” was provided to guide inclusion decisions. Mixed-methods studies were excluded to ensure methodological consistency and the depth of qualitative synthesis.

In the third stage, full texts were thoroughly reviewed to determine eligibility based on their content. Studies were excluded if they did not focus explicitly on the lived experiences of women with infertility—for example, studies addressing only miscarriage or general healthcare services (29 studies) or those limited strictly to clinical or medical aspects without experiential data (14 studies). Ultimately, 22 qualitative studies met the inclusion criteria and were selected for meta-synthesis. A detailed flowchart of the selection process is presented in

Figure 1.

This study employed qualitative meta-synthesis, following the thematic synthesis approach of Thomas and Harden (2008) [

12], integrated with procedural steps proposed by Song [

13]. Specifically, Thomas and Harden’s method provided the overarching analytical framework—including data extraction, inductive coding, theme development, and interpretive synthesis—while Song’s modifications structured the procedural flow of the synthesis. Song’s framework emphasizes iterative cross-checking, researcher reflexivity, and context-sensitive analysis. To reduce researcher subjectivity and ensure analytical rigor, multiple strategies were employed: (1) triangulation through discussions with a professor specializing in women’s health nursing and a nurse specializing in infertility, and (2) memo writing to document analytical decisions and assumptions. These steps enhanced transparency and trustworthiness in the interpretive process.

By combining these two approaches, the study ensured methodological consistency and cultural sensitivity, thus enhancing the originality of the synthesis process. The research was carried out in the following five stages.

1) Stage 1: Literature search and selection

Studies were selected based on predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria: qualitative design, relevance to infertility experiences, and language (English or Korean). Mixed-methods studies were excluded to maintain methodological consistency and emphasize qualitative depth. A systematic search was conducted across major databases, and relevant articles were organized using Microsoft Excel.

2) Stage 2: Quality assessment

The CASP Qualitative Checklist was used to evaluate methodological quality. Two independent reviewers assessed each study using a 10-item form, scoring each item as “Yes,” “No,” or “Unclear.” Scores were converted to percentages, and only studies scoring 85% or higher were included. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus discussion, enhancing reliability.

3) Stage 3: Data extraction

Key information and findings related to infertility experiences were extracted into a standardized Excel template. Data were independently reviewed by two researchers. Researcher reflexivity was maintained through memo writing, documenting decisions and perspectives throughout this process.

4) Stage 4: Text coding and development of descriptive themes

Line-by-line inductive coding preserved original language and meaning. Codes were grouped and refined into subcategories and descriptive themes through constant comparison. Two researchers independently coded a subset of data, resolving discrepancies through dialogue and guidance from a senior qualitative researcher to ensure analytical consistency.

5) Stage 5: Generation of analytical themes

Descriptive themes were abstracted into higher-order analytical themes, generating new conceptual insights into psychosocial and sociocultural dimensions of infertility. Researcher triangulation involved iterative discussions with a women’s health nursing professor and an infertility-specialized nurse, promoting validity and conceptual clarity. Divergent or ambiguous findings were explicitly examined to avoid overgeneralization.

5. Researcher Preparation

The researcher is a nurse with clinical experience in the maternal health department of a 110-bed women’s specialty hospital, closely involved in providing care and treatment for women experiencing infertility. The researcher reviewed both qualitative and quantitative infertility studies, applying Thomas and Harden’s thematic synthesis methodology for data interpretation. To mitigate researcher bias, reflexivity was practiced throughout the research process by documenting subjective perspectives in analytic memos and regularly consulting with interdisciplinary experts. Findings were derived through extensive discussions with a women’s health nursing professor and a nurse specializing in infertility care.

RESULTS

1. Literature Review and Analysis

Detailed information and analysis of the research findings are summarized in

Table 2 and

Appendix 1, and key results are discussed in the text. Participants in the reviewed studies had an average infertility diagnosis duration of 5 to 6 years, with approximately 80% undergoing 3 to 4 infertility treatments. Notable differences were observed between domestic and international study results.

Through thematic synthesis, six themes were identified, providing a systematic understanding of infertility experiences.

1) Theme 1: Struggles with identity and the pursuit of inner growth

Women experienced a profound identity crisis influenced by repeated assisted reproductive technology failures and societal expectations (A8 and A11), triggering emotional instability and self-doubt. Amid psychological pain, many sought to reconstruct their sense of self. Spousal support was crucial for navigating these emotional challenges and promoting inner transformation (B10). Spiritual reflection also emerged as a means to regain internal stability and redefine personal identity (B2).

2) Theme 2: Isolation and the reconstruction of resilience through support

Intense social pressures, family conflicts, and stigmatization resulted in profound loneliness and vulnerability among women (B1). These difficulties often led to alienation and psychological distress. Within these isolating experiences, emotional and informational support from peers and spouses became critical coping resources (A5 and B8). Gradually, women reinterpreted their infertility journeys (B7), and empathetic support helped alleviate the pain of repeated losses (B11).

3) Theme 3: Emotional turmoil and coping strategies for recovery

The emotional landscape of infertility was characterized by recurring anxiety, despair, and feelings of helplessness, influenced by personal and cultural contexts. Women adopted strategies such as couples counseling (A6), medical guidance (A2 and A3), and spiritual or ritual practices (B9) to manage emotional overload. These coping mechanisms were not immediate solutions but represented challenging processes of emotional recovery and meaning-making (B11).

4) Theme 4: Navigating economic hardship and social stigma with systemic support

Women undergoing infertility treatments faced significant economic strain (A2 and B1) from treatment-related expenses (A5), leading some to discontinue treatment (B7). Financial assistance (B6) and insurance support (A11) provided relief. Social stigma (A2 and B1) and associated psychological stress (A11) were mitigated through counseling and advocacy efforts (A4). Insensitive remarks exacerbated distress, highlighting the necessity of support (A1). Workplace policies (B5) were beneficial in achieving work-life balance.

5) Theme 5: Psychological tension between waiting and hope

The prolonged and uncertain process of waiting created significant emotional distress. Many women experienced repeated cycles of hope and loss, accompanied by fear and internalized stigma (A5, A1, and B3). Despite these emotional setbacks, women continually searched for meaning and possibilities for the future (A9). The psychological tension between waiting and hoping became central to their struggle, laying the groundwork for personal growth and deeper relationships. Achieving pregnancy marked a pivotal turning point, often restoring self-worth (B5).

6) Theme 6: Redefining marital and familial relationships amid crisis

Infertility exerted significant pressure on marital and familial relationships, frequently causing emotional distance and conflicting expectations (A1 and A11). Confronted with these tensions, some couples undertook painful yet necessary reflections on the meaning of parenthood. Through this crisis, they worked towards rebuilding mutual understanding and shared goals (A8). Over time, infertility experiences were reframed from purely negative events into opportunities for relational growth and a value-based redefinition of family (B3 and B9).

3. Model of Research Findings

The model was developed under the name Model of Psychological Changes and Resilience (PCR Model).

1) Model structure

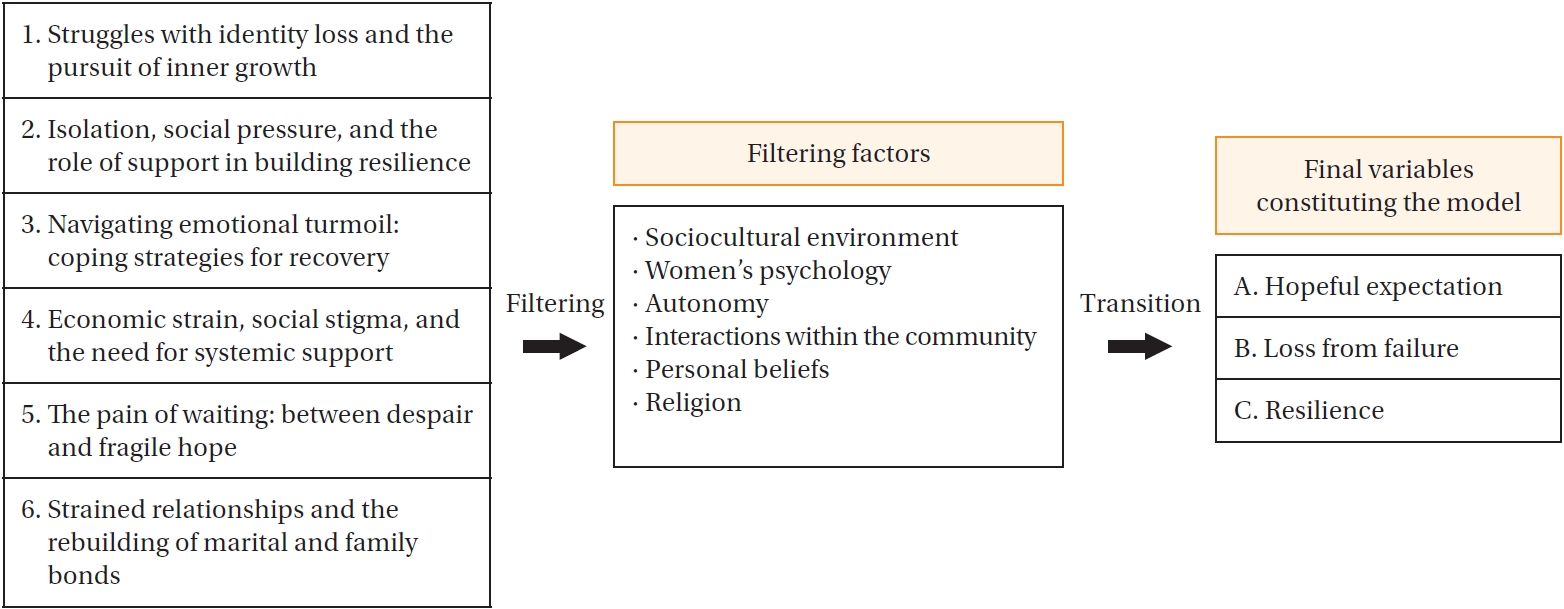

(1) Model structuring process

The model was constructed by synthesizing the six themes identified in the meta-synthesis. Variables necessary for building the model were comprehensively organized based on these themes. The detailed process of model construction is illustrated in

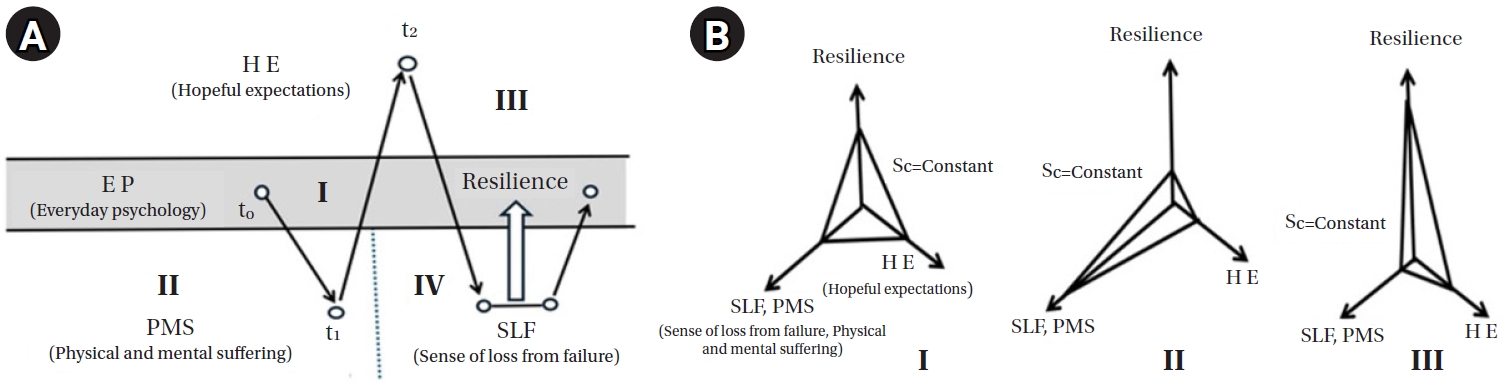

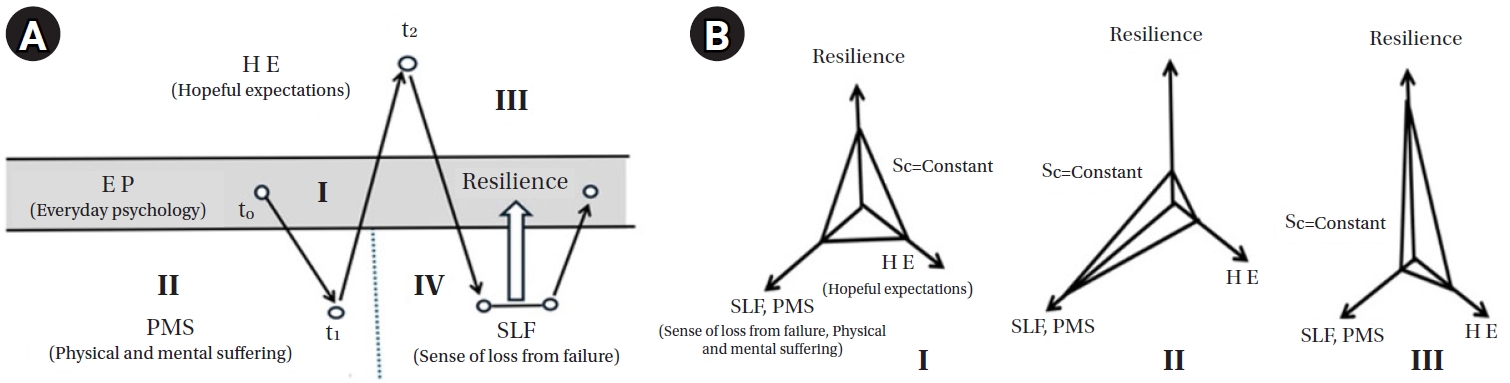

Figure 2.

(2) Filtering (F)

The filtering (F) process involves examining the six identified themes through various social perspectives to capture the core essence of women’s infertility experiences [

14]. This approach analyzes individual experiences within broader social contexts—including gender, race, religion, and culture—to uncover context-specific meanings [

15]. In modeling the psychological states of women with infertility, identifying elements connecting thematic findings with personal experiences is crucial. The filtering process thus distills the empirical psychological essence of infertility by translating broad social constructs into lived realities, an approach commonly used in sociological research [

16]. This study employed five key filtering elements: sociocultural environment, psychological state, autonomy, community interaction, and individual beliefs and religion. These elements mediate between individuals and society, reflecting concrete challenges faced by women with infertility. They significantly influence women’s daily lives [

17], forming the basis for identifying individual-level variables within the six thematic categories. The filtering process shifts the discourse on infertility from macro-level sociocultural narratives to micro-level understandings of personal psychological and emotional realities. Each theme was interpreted through these filtering elements: identity struggles through psychological states; isolation, support, and relationship strains through community interaction and emotional dynamics; coping strategies through autonomy; economic strain and stigma through sociocultural environment; and psychological tension in waiting through personal beliefs and religion. Filtering provided deeper sociocultural context for each theme. Through this analysis, diverse infertility experiences were synthesized into three core psychological constructs: hopeful expectations, sense of loss from failure, and psychological resilience.

(3) Transition (T)

The transition (T) process reconfigures infertility experiences into three core variables: expectation, loss, and resilience. This simplification aims to structurally analyze psychological fluctuations, identify the impacts of individual and social contexts, explain relationships within a theoretical model, and enhance research efficiency. These variables form a cyclical structure, highlighting the interconnected flow of hope, failure, and recovery, illuminating emotional and social changes throughout the infertility journey.

2) Model of psychological changes and resilience in women with infertility

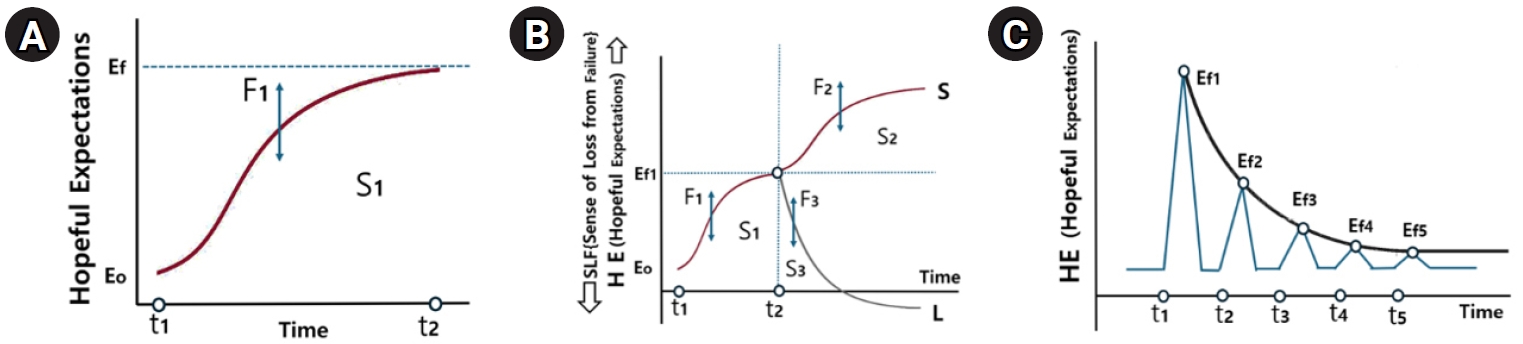

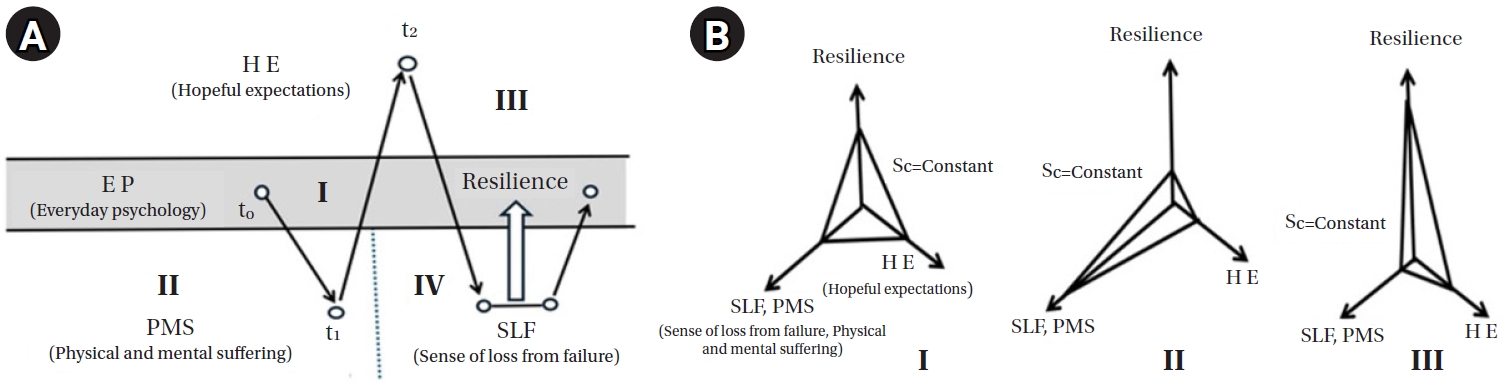

(1) Emotional fluctuations, resilience factors, and their interplay in women with infertility before and after treatment and pregnancy loss

Figure 3A outlines the psychological changes experienced by women with infertility across four stages. At t

0 (pre-treatment stage), women maintain a relatively stable or baseline emotional state (area I). This state represents a neutral psychological condition before emotional upheaval from infertility treatment begins. Between t

0 and t

1 (preparation phase), women start experiencing physical and psychological suffering, including side effects from medication, emotional stress, and financial strain, collectively defining area II. This phase initiates emotional instability. At t

1 (treatment initiation), positive emotions emerge, characterized by heightened hope and anticipation about potential pregnancy. These positive emotions form area III, signifying rising expectation, which peaks at t

2 (pregnancy confirmation point).

If pregnancy fails, emotional state plummets into area IV, marked by intense disappointment, grief, and loss. However, some women activate resilience mechanisms, gradually recovering to a more stable state, cycling back toward area I. This model was constructed based on qualitative findings. For example, study B3 reported women feeling “a thrilling hope” during early treatment, reflecting elevated expectation (E). Conversely, study A6 described profound self-blame and emptiness following repeated failures, illustrating significant emotional loss (L). Study A1 emphasized community support and religious faith in enabling women to “stand back up,” exemplifying resilience (R). In

Figure 3B, the psychological states after treatment outcomes are mathematically represented with the following relationship:

where E (expectation) refers to the degree of hope or anticipation a woman has regarding pregnancy success; L (loss) indicates the magnitude of emotional pain or grief following treatment failure; R (resilience) represents the internal or external factors that help in recovery; and C (constant) denotes the total psychological capacity or emotional bandwidth, assumed to be finite and constant during a treatment cycle.

This equation indicates that emotional energy is conserved and dynamically allocated across the three variables. Their sum remains constant, reflecting complementary relationships [

18]. For instance, a high level of expectation (E) may reduce available resilience (R) following a significant loss (L). Conversely, increasing R through support or coping strategies can mitigate L despite treatment failure.

In section II of

Figure 3B, pregnancy outcome determination represents a critical emotional inflection point. A failed outcome typically yields high L and low E, leaving resilience (R) as the primary determinant for psychological recovery. Section III shows that adequate resilience allows women to gradually stabilize emotionally, reducing the loss's impact. Without sufficient resilience, however, loss remains high, complicating recovery. This interdependence among E, L, and R, within the fixed emotional capacity C, underscores trade-offs and complementary dynamics between these variables.

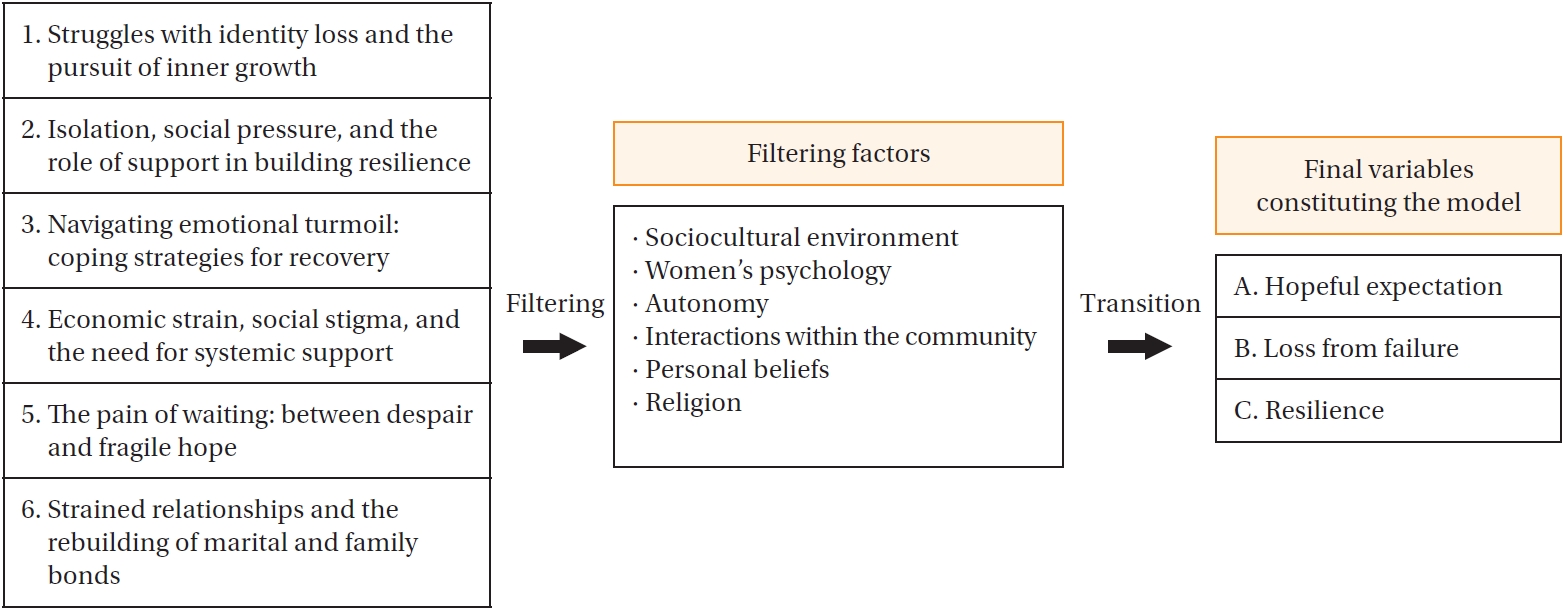

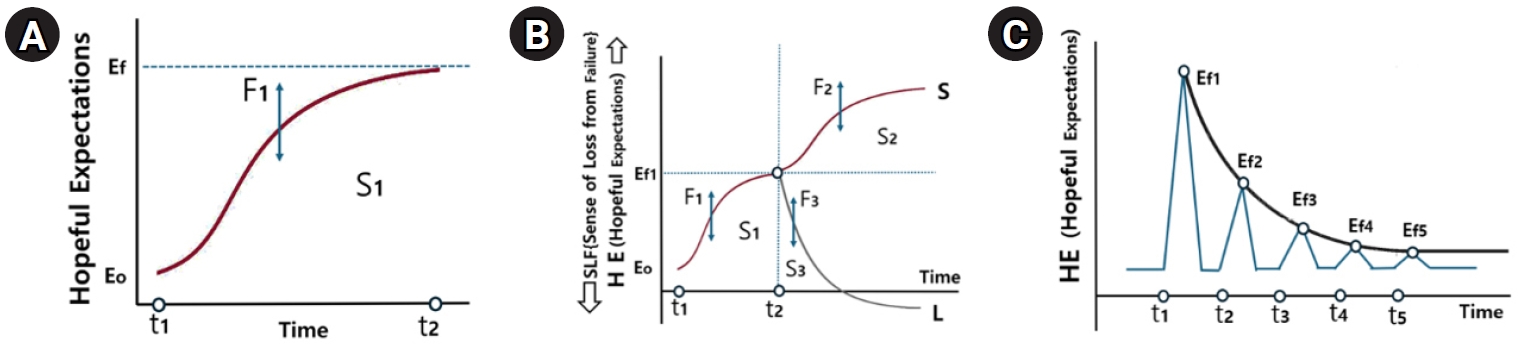

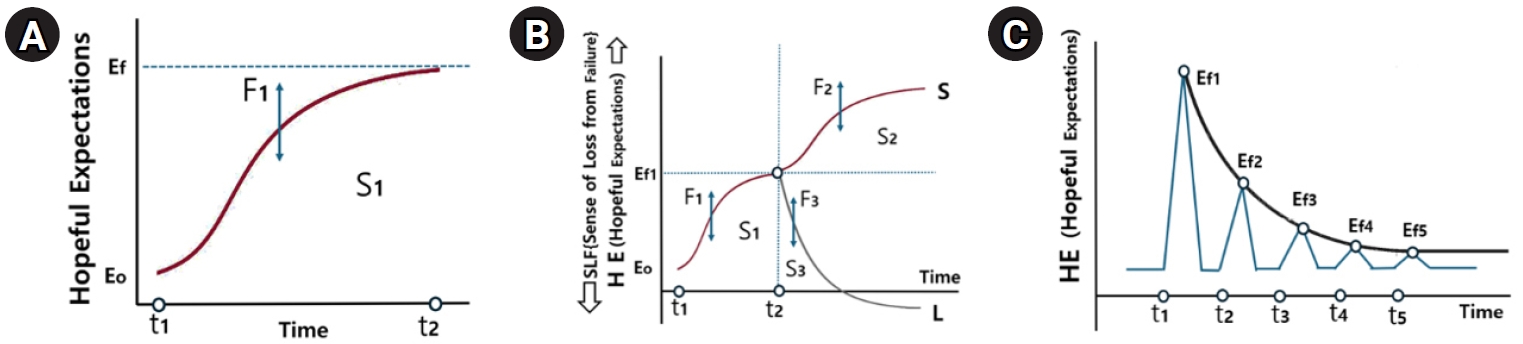

(2) Changes in expectation and loss over time in women with infertility

Figure 4A demonstrates the dynamic increase in expectation (E) throughout infertility treatment, divided into three psychological stages: (1) Preparation phase (pre-treatment): women experience confusion and distress due to uncertainty and insufficient information. Expectation (E) remains low, while anxiety is elevated. (2) Early to middle phase (post-treatment initiation): As treatment progresses and women receive feedback from professionals and others, E increases. The rate of increase is non-linear, following a logistic curve characterized by slow initial growth, accelerating with positive reinforcement. This progression can be mathematically represented by the following equation:

where Ef(t) represents the expectation level at time during treatment; E0 denotes the initial expectation level at the start of treatment; Ef indicates the saturation point of expectation, or the maximum achievable level; c is the growth rate constant, indicating how quickly expectation increases; and t refers to the time elapsed during the treatment process.

This equation models the gradual increase in hope over time, influenced by internal and external factors. It captures women’s emotional progression from initial uncertainty to cautious optimism.

(3) Late phase (just before pregnancy confirmation): Expectations plateau at a saturation point Ef1, due to growing anxiety regarding treatment outcomes. Women become emotionally cautious, mentally preparing for either result. This expectation change pattern is influenced by expectation-influencing factors (F1), where F1+ includes positive healthcare feedback, social support, stable living environment, past success, while F1− includes physical fatigue, financial strain, emotional burnout, partner conflict, repeated failures.

The area under the curve S1 (between t1 and t2) represents the total emotional investment in E. A greater F1 leads to higher peaks and larger emotional engagement.

In

Figure 4B, the determination of pregnancy at t2 leads to two diverging paths. Success path (S2) describes a pattern in which emotional states follow an S-curve as joy and relief build over time. F2+ factors (support, health stability, and medical reassurance) extend and elevate this positive trajectory, whereas F2– factors (early complications, trauma, and pressure) flatten or shorten this path. Failure path (S3) represents emotional states decline exponentially, shown as a steep drop on the L-curve. F3+ factors (e.g., high resilience, support, flexibility) moderate the fall, while F3– factors (e.g., age, financial depletion, repeated failures) intensify it. The S3 area reflects how long and deeply the woman experiences emotional loss after failure.

In

Figure 4C,

E declines exponentially with repeated pregnancy failures. This pattern is modeled by an exponential decay function:

where Ef(t) represents the expectation level at time t after treatment failure; Ef1 indicates the expectation level just before the result (final saturation point); c is the decay coefficient, representing how rapidly expectation declines over time; and t denotes the time since treatment failure.

A larger c means a steeper decline—that is, women lose hope faster as failures accumulate. In early cycles, hope may remain strong, but as attempts repeat, the psychological cost becomes harder to overcome, leading to diminished expectations and increased vulnerability.

DISCUSSION

This study constructed the PCR model to better understand the complex psychological processes experienced by women with infertility. The findings indicate that expectation, loss, and resilience are closely interrelated, significantly influencing emotional stability and coping strategies during infertility treatments. By moving beyond traditional biomedical approaches and integrating psychological, sociocultural, and existential dimensions, this model provides a dynamic framework for interpreting the emotional journey of women with infertility. In particular, incorporating theories by Hegel, Freud, and Frankl offers a holistic perspective on the internal conflicts and growth these women experience.

1. Desire for Recognition and Social Identity

Recognition is central to the psychological experience of infertility. As Hegel [

19] and Freud [

20] emphasized, identity formation occurs through recognition by others. In the context of infertility, recognition is often connected to fulfilling the culturally valued role of motherhood. When this recognition is unmet, it generates emotional distress and social isolation, particularly within societies strongly influenced by gender norms. Recognition thus becomes a driving force within the PCR model’s expectation-loss dynamics [

21,

22]. While previous studies often addressed recognition through social role theory or stigma theory, the PCR model uniquely highlights recognition as an existential and relational dynamic shaped by philosophical underpinnings (e.g., Hegel and Freud). This differentiates the PCR model from more behavioral or sociological frameworks regarding identity disruption.

Hope, described by Spinoza as “an uncertain joy” [

23], encapsulates the emotional cycles experienced by women undergoing infertility treatment. These cycles, frequently marked by repeated disappointment, align with Seligman’s theory of learned helplessness and the emotional strain caused by cognitive dissonance [

24,

25]. Drawing from Marx [

26], the concept of the instrumentalized body illustrates how women may perceive their bodies as fragmented tools during treatment—an objectification that erodes identity when reproductive success becomes the primary valued outcome. This objectification intensifies feelings of loss, particularly under sociocultural pressures. Althusser’s ideological state apparatus theory and Bourdieu’s concept of habitus explain how dominant norms and insufficient cultural capital pressure women to internalize societal expectations regarding motherhood, reinforcing the emotional toll of repeated treatment failures [

22,

27]. Unlike traditional definitions of “expectation” and “loss” in infertility literature—which often frame these terms clinically or biomedically (e.g., anticipated pregnancy outcomes, treatment failures)—this study redefines expectation as a socio-existential longing for recognition and fulfillment, and loss as a multi-layered disruption of selfhood, identity, and bodily agency.

In the PCR model, resilience represents more than mere recovery; it is an active process of redefining self and meaning amidst uncertainty. Frankl’s logotherapy provides a framework for understanding this transformation, emphasizing the pursuit of meaning through suffering [

28]. Women reconstruct their identities beyond motherhood, integrating infertility experiences into broader self-narratives. Stoic philosophy complements this approach by advocating for inner strength and acceptance, reinforcing resilience as an existential reorientation rather than simple adaptation. Thus, resilience is generative—it reshapes personal values and identities, highlighting its pivotal role in transitioning from loss to psychological renewal. This perspective extends beyond traditional psychological resilience theories, such as those by Masten or Rutter, which primarily focus on adaptive capacity and protective factors. Instead, this study draws from existential and philosophical frameworks, positioning resilience as a transformative force for identity reconstruction rather than merely a return to prior states.

Moreover, the PCR model diverges from existing frameworks by portraying resilience as a creative reorientation—rather than mere coping—where infertility is incorporated as a formative experience of meaning-making rather than a limitation to overcome.

CONCLUSION

This study synthesized findings from 22 qualitative studies on women’s infertility experiences, focusing on emotional changes and the cyclical interaction among expectation, loss, and resilience. Domestic research primarily addressed treatment processes (A4–8, A10–11), while international studies emphasized emotional and social contexts (B2–10). Six key themes were identified: identity transformation, resilience through familial roles, strategies for recovery, support systems, the psychological tension between waiting and hope, and shifts in marital dynamics. The proposed psychological resilience model illustrates how emotional responses fluctuate throughout infertility treatment, highlighting resilience as a central mediator in psychological recovery. Philosophical perspectives enrich the interpretation of these phases, providing deeper insights into women’s processes of meaning-making. Clinically, this model offers nurses and healthcare providers a structured framework to assess patients' emotional stages and implement tailored interventions—such as expectation management, grief counseling, and resilience-building programs—at appropriate times. From a policy standpoint, the model suggests the need for integrated psychosocial support services and mental health screening protocols within infertility care systems. These implications support transitioning toward more comprehensive, person-centered care.

Future longitudinal studies are necessary to validate the dynamic interactions within the model and explore the long-term influence of sociocultural and psychological variables.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declared no conflict of interest.

-

FUNDING

None.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

None.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data can be obtained from the corresponding authors.

Figure 1.Flowchart of article extraction process.

Figure 2.Structuring process of the model.

Figure 3.Emotional changes and resilience in infertility: expectation, loss, and recovery. (A) Emotional changes and recovery factors in infertility treatment and pregnancy failure. (B) Changes in expectation, sense of loss and resilience in women with infertility undergoing treatment.

Figure 4.Changes in expectation and loss across the infertility treatment process and pregnancy confirmation. (A) Hopeful expectation before pregnancy confirmation. (B) The shift in expectations and loss during treatment. (C) Declining expectations with repeated treatment failures.

Table 1.Quality Appraisal of Included Studies

|

Items |

Korean studies |

International studies |

|

A1 |

A2 |

A3 |

A4 |

A5 |

A6 |

A7 |

A8 |

A9 |

A10 |

A11 |

B1 |

B2 |

B3 |

B4 |

B5 |

B6 |

B7 |

B8 |

B9 |

B10 |

B11 |

|

Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

C |

C |

C |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

C |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

C |

Y |

C |

|

Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

N |

N |

C |

Y |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

Y |

N |

N |

Y |

C |

N |

C |

N |

C |

|

Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Is there a clear statement of findings? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

How valuable is the research? |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

Y |

|

Percentage of met CASP (%) |

100 |

100 |

100 |

95 |

100 |

85 |

85 |

90 |

100 |

100 |

90 |

100 |

85 |

100 |

90 |

90 |

100 |

95 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

90 |

Table 2.Overview of Studies Included in the Meta-Synthesis

|

No. |

First author (year) |

Objective |

Infertility diagnosis period |

Experiences with infertility treatments (%) |

Data collection |

Data analysis |

Findings |

|

A1 |

Jeong (2014) |

Resilience process of women with infertility |

Avg. 3.7 years |

61.5% (8 out of 13) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Phenomenology (Colaizzi) |

Psychological journey of pregnancy and infertility |

|

Impact of familial and societal expectations |

|

Recovery and new beginnings |

|

A2 |

Jeong (2014) |

Infertility experiences: pain and coping |

Avg. 8.3 years |

16.7% (1 out of 6) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Grounded theory method (Strauss & Corbin) |

Determinism and identity crisis |

|

Idealized motherhood and the search for renewal |

|

A3 |

Jeong (2017) |

Examines social support experiences of infertile women |

Avg. 5.9 years |

66.7% (4 out of 6) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Phenomenology (Giorgi) |

Expectant waiting |

|

Worrying waiting |

|

Confronting reality |

|

My world changes |

|

Facing myself again |

|

A4 |

Ryu (2019) |

Women’s infertility treatment realities |

(–) |

(–) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Thematic analysis method |

Infertility and exile |

|

ART and the uncertainty of hop |

|

A5 |

Yang (2019) |

To explore the impact, challenges, and coping in infertility treatment |

(–) |

100% (mean number of treatments: 3.5) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Thematic analysis method |

The deteriorating mind |

|

Strained relationships |

|

Balancing challenging work and treatment |

|

The endless torture of hope without results |

|

A6 |

Baek (2020) |

Explores the pain of repeated infertility treatment failures |

(–) |

100% (mean number of treatments: 4) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Phenomenology (Colaizzi) |

Objectified body and elusive fortune |

|

Lonely struggle for recognition and pregnancy |

|

A7 |

Son (2020) |

Examines the lived experiences of women over 35 undergoing infertility treatment |

Avg. 3 years |

100% (mean number of treatments: 4.5) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Phenomenology (Colaizzi) |

Anxiety due to uncertainty |

|

Depression |

|

Strained relationships in distress |

|

Willingness toward pregnancy |

|

A8 |

Oh (2021) |

Explores and analyzes infertility treatment experiences of aging women |

Avg. 3.7 years |

Two treatments: 37.5% |

Semi-structured interviews |

Phenomenology (Colaizzi) |

Trials and challenges of treatment |

|

One treatment: 62.5% |

Hope and value in the experience |

|

A9 |

Lee (2021) |

Explores women's experiences from infertility to pregnancy |

Avg. 4 years |

100% (mean number of treatments: 2) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Phenomenology (Giorgi) |

The meant-to-be mother |

|

The longing for a child |

|

The pain of infertility treatment |

|

Ascending to motherhood |

|

A10 |

Jeon (2022) |

Examines coping experiences with infertility treatment |

(–) |

(–) |

In-depth individual interviews |

(–) |

Childbirth burden and healthcare access challenges |

|

Lack of psychological and emotional support |

|

A11 |

Park (2024) |

Abandonment process in women discontinuing infertility treatment |

Avg. 8.2 years |

61.5% (8 out of 13) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Grounded theory method (Strauss & Corbin) |

Psychological burden and social conflicts of infertility |

|

Support, Comfort, and Adaptation |

|

Traditional expectations and new paths |

|

B1 |

Ranjbar (2015) |

Examines and explains infertility treatment experiences of pregnant women |

6 months–15 years |

0–5 treatments |

In-depth individual interviews |

Content analysis method |

Struggle to achieve pregnancy |

|

Fear and uncertainty |

|

Breaking free from stigma |

|

Pursuit of husband’s satisfaction |

|

B2 |

Dierickx (2018) |

Explores the impact of infertility on women's lives |

(–) |

(–) |

In-depth individual interview |

Thematic analysis method |

The multidimensional impact of infertility |

|

Gender and pro-natal norms |

|

Respondent’s position and infertility experience |

|

B3 |

Hasanpoor-Azghady (2019) |

Explains the psychosocial process of the social construction of infertility |

Avg. 5.3 years |

Average treatment duration: 3.3 years |

In-depth individual interviews |

Grounded theory method (Strauss & Corbin) |

Marital and social interactions |

|

Psychological and social impact of infertility |

|

Treatment and spiritual growth |

|

B4 |

Aghakhani (2020) |

Explores the infertility experiences of Iranian women |

(–) |

(–) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Content analysis method |

Shock |

|

Reaction |

|

Processing |

|

Adjustment |

|

B5 |

Ofosu-Budu (2020) |

To explore infertile women’s experiences |

(–) |

(–) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Thematic analysis method |

Emotional experiences |

|

Social support and challenges |

|

B6 |

Kiani (2021) |

Investigates anxiety factors and their impact on the quality of life of infertile women |

Avg. 8.2 years |

Medication treatment: 26.6% |

In-depth individual interviews |

Content analysis method |

Infertility-related concerns |

|

Infertility treatment: 53.2% |

Coping with infertility |

|

Egg donation: 20.2% |

|

|

B7 |

Taebi (2021) |

Explores the concept of infertility stigma based on women’s experiences and perceptions |

~5 years: 53% |

(–) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Thematic analysis method |

Stigma profile |

|

5–10 years: 35.3% |

Self-stigma |

|

More than 10 years: 11.7% |

Defense mechanisms |

|

Balancing |

|

B8 |

Halkola (2022) |

Explains factors supporting coping in women with infertility |

(–) |

(–) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Inductive analysis method |

Personal resources |

|

Well-functioning relationships |

|

Seeking help |

|

Adaptability to life without children |

|

B9 |

Sambasivam (2023) |

Evaluates factors affecting helplessness, fatigue, and coping in infertile women |

(–) |

Treatment duration: 6 months to 4 years |

In-depth individual interviews |

Phenomenology (Colaizzi) |

Intersection of hope and despair |

|

Social isolation and spiritual/mental resources |

|

Coping and recovery strategies |

|

B10 |

Adane (2024) |

Explores psychological issues and coping strategies of infertile women |

(–) |

(–) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Thematic analysis method |

Psychological challenges and coping of infertile women |

|

Psychological difficulties |

|

Coping strategies of infertile women |

|

B11 |

Keten Edis (2024) |

Investigates infertile women’s use and views on complementary and traditional practices |

Avg. 5.6 years |

(–) |

In-depth individual interviews |

Braun and Clarke's analysis method |

Reasons for using CST practices |

|

Effectiveness of complementary and traditional practices |

REFERENCES

- 1. Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service. Analysis of infertility treatment trends [Internet]. Wonju: Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service; 2023 [cited 2023 May 25]. Available from: https://www.hira.or.kr/bbsDummy.do?pgmid=HIRAA020041000100&brdScnBltNo=4&brdBltNo=10880

- 2. Statistics Korea. Mean age of childbearing [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 28]. Available from: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?sso=ok&returnurl=https%3A%2F%2Fkosis.kr%3A443%2FstatHtml%2FstatHtml.do%3Flist_id%3DA21%26obj_var_id%3D%26seqNo%3D%26eType%3D%26tblId%3DDT_1B81A12%26vw_cd%3DMT_ZTITLE%26orgId%3D101%26path%3D%252Fcommon%252Fmeta_onedepth.jsp%26conn_path%3DK2%26itm_id%3D%26lang_mode%3Dko%26scrId%3D%26

- 3. Kim HO, Sung N, Song IO. Predictors of live birth and pregnancy success after in vitro fertilization in infertile women aged 40 and over. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2017;44(2):111-7. https://doi.org/10.5653/cerm.2017.44.2.111

- 4. Durning PE, Williams RS. Factors influencing expectations and fertility-related adjustment among women receiving infertility treatment. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(Suppl 1):S101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.07.256

- 5. Aimagambetova G, Issanov A, Terzic S, Bapayeva G, Ukybassova T, Baikoshkarova S, et al. The effect of psychological distress on IVF outcomes: reality or speculations? PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0242024. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242024

- 6. Maroufizadeh S, Karimi E, Vesali S, Omani Samani R. Anxiety and depression after failure of assisted reproductive treatment among patients experiencing infertility. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;130(3):253-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.03.044

- 7. Forsythe S. Social stigma and the medicalisation of infertility. J Man Anthrop Stud Assoc. 2009;28:22-36.

- 8. Park KH. Trend of research on psychological support for infertility in South Korea: a review of journals and theses between 1988-2020. Crisisonomy. 2020;16(6):1-16. https://doi.org/10.14251/crisisonomy.2020.16.6.1

- 9. Boonmongkon P. Family networks and support to infertile people. In: Vayena E, Rowe PJ, Griffin PD, editors. Current practices and controversies in assisted reproduction. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2002. p. 281-6.

- 10. Son HM. A literature review on qualitative meta-synthesis. J Korean Assoc Qual Res. 2020;5(2):109-18. https://doi.org/10.48000/KAQRKR.2020.5.109

- 11. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP qualitative studies checklist [Internet]. Oxford: Critical Appraisal Skills Programme; 2024 [cited 2024 December 27]. Available from: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

- 12. Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- 13. Song M. Qualitative meta synthesis methodology and exploration and implications in special education research. J Spec Educ. 2022;29(3):36-66. https://doi.org/10.34249/jse.2022.29.3.36

- 14. Kim J. Study on the development of collaborative filtering systems and its application. J Inst Soc Sci. 2018;29(2):197-209. https://doi.org/10.16881/jss.2018.04.29.2.197

- 15. Jeong D, Kim J, Kim GN, Heo JW, On BW, Kang M. A proposal of a keyword extraction system for detecting social issues. J Intell Inform Syst. 2013;19(3):1-23. https://doi.org/10.13088/jiis.2013.19.3.001

- 16. Lee JH. Excess of relationships, excess of interactions: network size and interaction quality on Facebook. Inst Commun Res. 2016;53(1):217-66. https://doi.org/10.22174/jcr.2016.53.1.217

- 17. Lee KA. A study on feminist ministry for the women in subfertility. J Korean Fem Theol. 2016;82:118-42.

- 18. Saelor TK, Ness O, Holgersen H, Davidson L. Hope and recovery: a scoping review. Adv Dual Diagn. 2014;7(2):63-72. https://doi.org/10.1108/ADD-10-2013-0024

- 19. Hegel GW. Phenomenology of spirit. Lim SJ, translator. Paju: Hangilsa; 2005. p. 128-40.

- 20. Freud S. Introduction to psychoanalysis. Choi SJ, translator. Goyang: Dodeulsaekim; 2024. p. 218-30.

- 21. Beck-Gernsheim E. The invention of motherhood. Lee JW, translator. Seoul: Alma; 2014. p. 157-62.

- 22. Boggs B. The art of waiting. Lee KA, translator. Seoul: Chaekilneun Suyoil; 2020. p. 31-42, 210-5.

- 23. Spinoza B. Ethics. Kang YG, translator. Seoul: Seogwangsa; 2007. p. 240-50.

- 24. Seligman ME. Learned optimism. Choi HY, translator. Seoul: 21st Century Books; 2008. p. 38-42.

- 25. Benyamini Y, Johnston M, Karademas EC, editors. Between stress and hope: from a disease-centered to a health-centered perspective. 1st ed. Westport, CT: Praeger; 2008. p. 141-66.

- 26. Marx K. Capital. Kim SH, translator. Seoul: Bibong Publishing; 2015. p. 249-60.

- 27. Heo SH. Postmodernism and subject 6: Althusser and ideological subject. J Third Age. 2017;105:12-9.

- 28. Frankl VE. Man’s search for meaning. Lee SH, translator. Paju: Cheong-A Publishing; 2020.

Appendices

Appendix 1.

- List of Included Studies

A1. Jeong KI. A study on resilience in women experiencing infertility: a grounded theory approach [dissertation]. Seoul: Sungkyunkwan University Graduate School; 2014.

A3. Jeong YM, Kang SK. A phenomenological study on infertile experiences of women: waiting for meeting. Stud Life Cult. 2017;44:271-319.

A6. Baek EH, Oh SE, Lee HS. The suffering experiences of infertile women due to repeated assisted reproductive technology failure. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the Conference of the Korean Society of Maternal and Child Health; 2020 November 28; Virtual event.

A8. Oh HJ. The experiences and significance of assisted reproductive technologies for the infertile women with the age of 35 or higher [master’s thesis]. Seoul: Graduate School of Health Nursing, Chung-Ang University; 2021.

A9. Lee M, Cho H, Kim J. A phenomenological study on the psychological difficulties experienced during pregnancy of infertile women. J Music Hum Behav. 2021;2(1):19-36.

A11. Park EM. Experiences of in infertile woman quitting in vitro fertilization procedures [dissertation]. Daegu: Graduate School, Kyungpook National University; 2024.

B1. Ranjbar F, Behboodi-Moghadam Z, Borimnejad L, Ghaffari SR, Akhondi MM. Experiences of infertile women seeking assisted pregnancy in Iran: a qualitative study. J Reprod Infertil. 2015;16(4):221-8.

B2. Dierickx S, Rahbari L, Longman C, Jaiteh F, Coene G. 'I am always crying on the inside': a qualitative study on the implications of infertility on women's lives in urban Gambia. Reprod Health. 2018;15:151.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0596-2

B3. Hasanpoor-Azghady SB, Simbar M, Vedadhir AA, Azin SA, Amiri-Farahani L. The social construction of infertility among Iranian infertile women: a qualitative study. J Reprod Infertil. 2019;20(3):178-90.

B4. Aghakhani N, Marianne Ewalds-Kvist B, Sheikhan F, Merghati Khoei E. Iranian women's experiences of infertility: a qualitative study. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2020;18(1):65-72.

https://doi.org/10.18502/ijrm.v18i1.6203

B6. Kiani Z, Simbar M, Hajian S, Zayeri F. Quality of life among infertile women living in a paradox of concerns and dealing strategies: a qualitative study. Nurs Open. 2021;8(1):251-61.

https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.624

B8. Halkola ST, Koivula M, Aho AL. A qualitative study of the factors that help the coping of infertile women. Nurs Open. 2022;9(1):299-308.

https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1062

B9. Sambasivam I, Jennifer HG. Understanding the experiences of helplessness, fatigue and coping strategies among women seeking treatment for infertility: a qualitative study. J Educ Health Promot. 2023;12:309.

https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_1600_22

B11. Keten Edis E, Bal S, Koc E. Complementary, supportive and traditional practice experiences of infertile women in Türkiye: a qualitative study. BMC Complement Med Ther. 2024;24:302.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-024-04604-0