Abstract

-

Purpose

The incidence of gynecological cancers is increasing, presenting significant challenges for patient care and outcomes. Perceived stress and negative affect can impede self-care behaviors and reduce health-related quality of life (HRQoL). This study examined the mediating effects of negative affect and cancer coping on the relationship between perceived hospital stress and HRQoL among patients with gynecological cancer.

-

Methods

A cross-sectional mediation analysis was conducted with 118 gynecological cancer patients recruited from the outpatient clinic of a university hospital (October 2023 to February 2024). Participants completed validated instruments assessing perceived stress, negative affect, cancer coping, and HRQoL. Data were analyzed using Spearman’s correlations and the PROCESS macro (Model 4) with 95% bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs).

-

Results

Perceived stress was significantly correlated with negative affect (r=.58, p<.001), cancer coping (r=.23, p=.012), and HRQoL (r=–.45, p<.001). Negative affect was correlated with HRQoL (r=–.59, p<.001). Furthermore, negative affect and cancer coping mediated the relationship between stress and HRQoL (B=–0.18, 95% CI=–0.27 to –0.11 and B=0.04, 95% CI=0.01 to 0.08, respectively).

-

Conclusion

Negative affect and cancer coping significantly mediated the relationship between hospital stress and HRQoL. Targeted interventions aiming to reduce stress and strengthen emotional and coping strategies could enhance HRQoL among gynecological cancer patients.

-

Key Words: Uterine neoplasms; Stress, physiological; Psychological distress; Coping skills; Quality of life

INTRODUCTION

According to GLOBOCAN 2022, the incidence of cancers, including gynecological cancers, is increasing worldwide [

1]. Advances in early detection and treatment have substantially improved survival rates, with over 80% of cervical and endometrial cancer patients and 65.1% of ovarian cancer patients surviving beyond 5 years in Korea [

2]. These improvements in cancer management underscore the necessity of focusing not only on survival but also on enhancing quality of life among gynecological cancer survivors [

1,

2].

Despite improved prognoses, many survivors continue to experience persistent psychological and emotional challenges, particularly related to perceived stress, negative affect, and coping mechanisms [

3-

6]. Such emotional difficulties often arise from the initial cancer diagnosis, side effects related to treatment, and daily stressors including fatigue, anxiety, and altered body image [

4-

6]. Additionally, the loss of reproductive organs may exacerbate concerns about sexual identity and body image, thereby increasing perceived stress and diminishing health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [

7]. Recent evidence indicates perceived stress is significantly associated with higher symptom burden, regardless of cancer type or treatment modality, explaining a substantial proportion of variance in symptom severity and distress among survivors [

8]. Thus, patient-centered care plans are crucial for alleviating perceived stress and improving HRQoL in gynecological cancer survivors [

5,

7].

Given these challenges, it is important to understand how emotional responses and coping behaviors influence well-being among gynecological cancer survivors. According to the transactional model of stress and coping [

9], individuals cognitively appraise cancer-related stress and adopt various coping strategies that directly influence psychological adjustment. Negative affect—including emotions such as fear, sadness, and anger—is commonly experienced, especially during diagnosis and treatment phases [

4,

6]. Conversely, positive affect can emerge during recovery, promoting emotional balance and resilience [

9,

10].

Cancer coping involves mobilizing personal and social resources to manage perceived cancer-related stress. Such strategies include planning, positive reframing, seeking support, emotional expression, and asking for help [

11]. Positive coping strategies foster psychological and physical adaptation, potentially enhancing engagement in treatment and facilitating recovery [

12,

13]. These mechanisms suggest that how patients manage emotional distress and stress critically influences their overall quality of life.

Previous studies have identified predictors of HRQoL in gynecological cancer patients, including social support, coping strategies, perceived stress, marital status [

13], body image [

3], abdominal complaints, activity levels, depression [

2], and changes in physical, mental, and sexual health [

14]. Unlike prior research focusing on individual factors, this study examines the combined mediating roles of negative affect and coping strategies within the transactional model of stress and coping [

9]. By systematically evaluating their joint impact on HRQoL, this study offers deeper insights into perceived stress adaptation mechanisms and actionable guidance for tailored nursing interventions. Therefore, the present study aims to investigate the mediating effects of negative affect and cancer coping in the relationship between perceived stress and HRQoL. A parallel multiple mediation model (PROCESS Macro) was applied, simultaneously entering both mediators to assess their individual and combined indirect effects. The research hypotheses are as follows: (1) Perceived stress would be correlated with negative affect, cancer coping, and HRQoL; (2) Negative affect and cancer coping would affect HRQoL; (3) Perceived stress would influence HRQoL; and (4) Negative affect and cancer coping would mediate the relationship between perceived stress and HRQoL.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study utilized quantitative mediation analysis to investigate the mediating roles of negative affect and cancer coping in the relationship between perceived stress and HRQoL among gynecological cancer patients.

2. Setting and Samples

Participants were recruited from a university-affiliated gynecological outpatient clinic in Seoul, South Korea. The eligibility criteria included age ≥18 years, a diagnosis of gynecological cancer (cervical, endometrial, or ovarian), the ability to complete the questionnaire independently, and voluntary participation. Exclusion criteria were a previous diagnosis of another cancer or current psychotherapy treatment. The sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1.7 for linear regression analysis (α=.05, power=.80, f

2=.15), suitable for detecting medium-sized effects. According to Hayes [

15], approximately 100 to 150 participants are sufficient for simple and parallel multiple mediation analyses employing bootstrapping. Of the 150 individuals initially screened, 118 participants (n=63 cervical, n=32 endometrial, n=23 ovarian cancer) met the eligibility criteria and completed the study without missing data, negating the need for data imputation. Efforts were made to include participants from diverse demographic backgrounds to minimize selection bias.

1) General characteristics

Participants’ general characteristics were assessed using an 11-item questionnaire derived from previous research [

6]. These items included age, spouse status (presence or absence), educational level, employment status, religion, presence of a primary family caregiver, medical payment methods, responsibility for housework or childcare, type of gynecological cancer, disease duration, and treatment modalities.

2) Perceived stress

Perceived stress was measured using the validated Korean Hospital Stress Rating Scale (K-HSRS) [

16], originally developed by Volicer and Bohannon [

17]. The scale comprises 13 items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=not at all, 5=very severe), with total scores ranging from 13 to 65. Higher scores indicate greater perceived stress. Cronbach’s α values were .93 in Volicer and Bohannon’s study [

17], .93 in Kang’s validation [

16], and .89 in this study.

3) Negative affect

Negative affect was assessed using the validated Korean version of the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (K-PANAS) [

18], following written approval for its use. The original questionnaire was developed and validated by Watson et al. [

19]. Negative affect was measured by 10 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=very slightly or not at all, 5=extremely), yielding total scores ranging from 10 to 50, with higher scores indicating greater negative affect. Cronbach’s α was .85 in the study of Watson et al. [

19], .87 in the Korean validation study by Lee et al. [

18], and .91 in this study.

4) Cancer coping

Cancer coping was evaluated using the validated Korean Cancer Coping Questionnaire (K-CCQ), administered after obtaining written approval [

20]. The Cancer Coping Questionnaire (CCQ) was originally developed by Moorey et al. [

11]. The K-CCQ consists of two subscales: individual coping (14 items) and interpersonal coping (9 items). Items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1=not at all, 4=very frequently), with total scores ranging from 23 to 92. Higher scores indicate stronger coping abilities. Cronbach’s α values for individual and interpersonal coping ranged from .72 to .90 in the original K-CCQ validation [

20] and were .94 and .91, respectively, in this study.

5) Health-related quality of life

HRQoL was assessed using the 27-item Korean version of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G), which measures four domains of HRQoL in cancer patients: physical (7 items), social (7 items), emotional (6 items), and functional well-being (7 items). The FACT-G was initially developed and validated by Cella et al. [

21]. The Korean version was approved and obtained from

https://www.facit.org/measures/fact-g. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (0=not at all, 4=very much), with a total score range of 0 to 108. Higher scores reflect better HRQoL. Cronbach’s α was .89 in Cella et al.’s validation [

21] and .86 in this study.

Data were collected from October 10, 2023, to February 28, 2024. Approval from the chief directors of medical and nursing departments was first obtained after explaining the study’s purpose. Subsequently, a recruitment notice was displayed in the gynecological outpatient clinic. Participants who expressed interest were provided detailed information regarding the study’s objectives, procedures, confidentiality and anonymity assurances, the non-collection of personally identifiable information, and their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. Completing the questionnaire required approximately 20 minutes, and participants received a small incentive of $5 upon completion.

5. Ethical Considerations

This study adhered strictly to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval from the institutional review board (IRB No: GCI 2023-07-014-002). All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment.

6. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 23.0 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) to explore participant characteristics and evaluate perceived stress, negative affect, cancer coping, and HRQoL. Descriptive statistics and frequency analysis were conducted, and the internal consistency reliability of all scales was verified using Cronbach’s α coefficients. Due to partial violations of normality assumptions (as assessed by the Shapiro-Wilk test), non-parametric tests—including the Mann-Whitney U test and Kruskal-Wallis test with Bonferroni post hoc adjustments—were applied to compare group differences.

Spearman’s correlation analysis was used to examine relationships among perceived stress, negative affect, cancer coping, and HRQoL. Mediating effects of negative affect (mediator 1) and cancer coping (mediator 2) on the relationship between perceived stress (independent variable) and HRQoL (dependent variable) were evaluated using Hayes’ PROCESS macro (Model 4), employing 5,000 bootstrap samples to test indirect effects for significance. All statistical analyses were rigorously conducted to ensure the validity and reliability of the mediation model.

RESULTS

1. Mean Scores of Perceived Stress, Negative Affect, Cancer Coping, and HRQoL

The mean scores for perceived stress, negative affect, cancer coping, and HRQoL were 2.76±0.75, 2.19±0.85, 2.28±0.60, and 2.80±0.50, respectively. Within cancer coping, the subscale mean scores were 2.35±0.61 for individual coping and 2.18±0.80 for interpersonal coping. The HRQoL domain scores were as follows: physical well-being (3.19±0.75), social well-being (2.16±0.79), emotional well-being (2.86±0.78), and functional well-being (2.99±0.69) (

Table 1).

Regarding participants’ characteristics, the mean age was 43.92±9.39 years, with 32.2% aged 18 to 39 years and 53.4% aged 40 to 54 years. In terms of marital status, 67.8% lived with their spouse. Primary caregivers provided care for 84.7% of participants. Additionally, 78.0% reported being employed, 49.2% identified as religious, and 76.3% had attained college-level education or higher. Regarding medical fee payment methods, 70.3% used support from public or private cancer insurance. Furthermore, 71.2% experienced concurrent burdens related to housework or childcare responsibilities. Concerning cancer types, 53.4% of participants were diagnosed with cervical cancer, 27.1% with endometrial cancer, and 19.5% with ovarian cancer. The mean disease duration was 39.41±29.83 months. Regarding treatment modalities, 82.2% received single-modality cancer treatments (e.g., surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation therapy) (

Table 2).

The results of the Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test with Bonferroni multiple comparison showed that perceived stress was significantly higher among ovarian cancer patients compared to cervical cancer patients (

z=10.51,

p=.005). Negative affect was significantly higher among participants who were religious (

z=–1.97,

p=.049) and paid their medical fees themselves (

z=–2.00,

p=.045). Moreover, cancer coping was significantly higher among those who lived with their spouses (

z=–3.26,

p=.001), and who were cared for by their primary caregivers (

z=–2.35,

p=.019). HRQoL was lower among participants without primary caregivers (

z=–2.48,

p=.013) and those who received combination cancer therapy (

z=–3.04,

p=.002) (

Table 2).

Spearman correlation analysis showed that perceived stress was significantly correlated with negative affect (r=.58,

p<.001), cancer coping (r=.23,

p=.012), and HRQoL (r=–.45,

p<.001). Additionally, negative affect was correlated with HRQoL (r=–.59,

p<.001) (

Table 3). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 (“Perceived stress would be correlated with negative affect, cancer coping, and HRQoL”) was accepted (

Table 3).

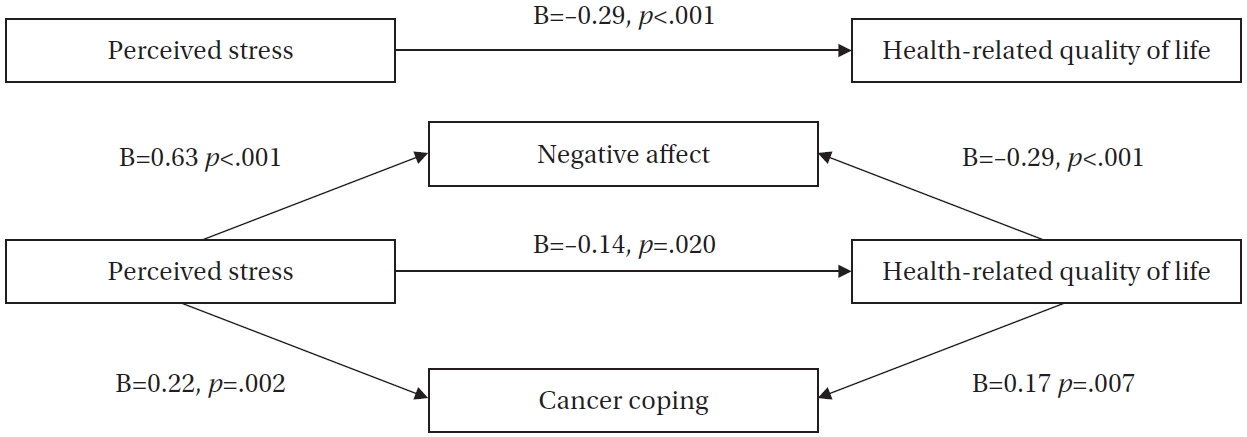

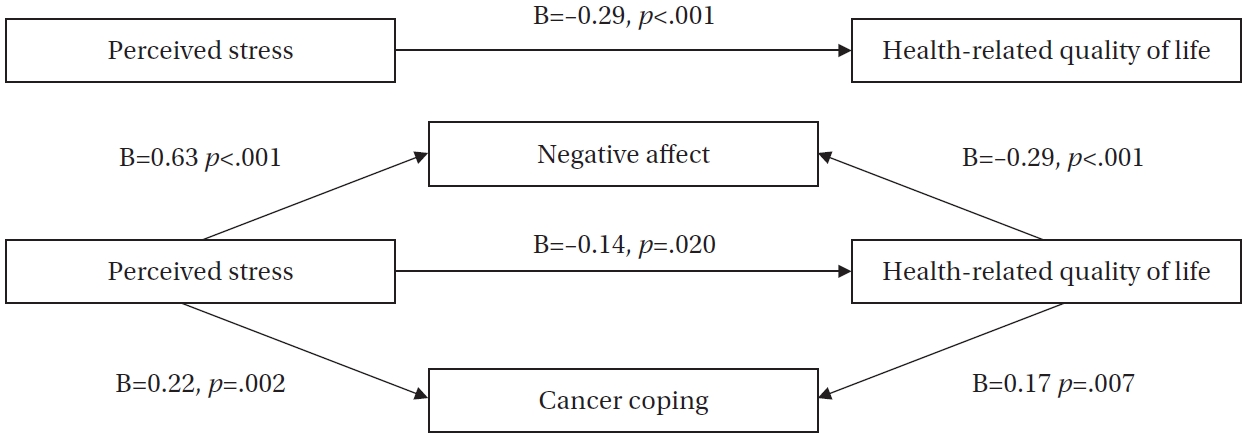

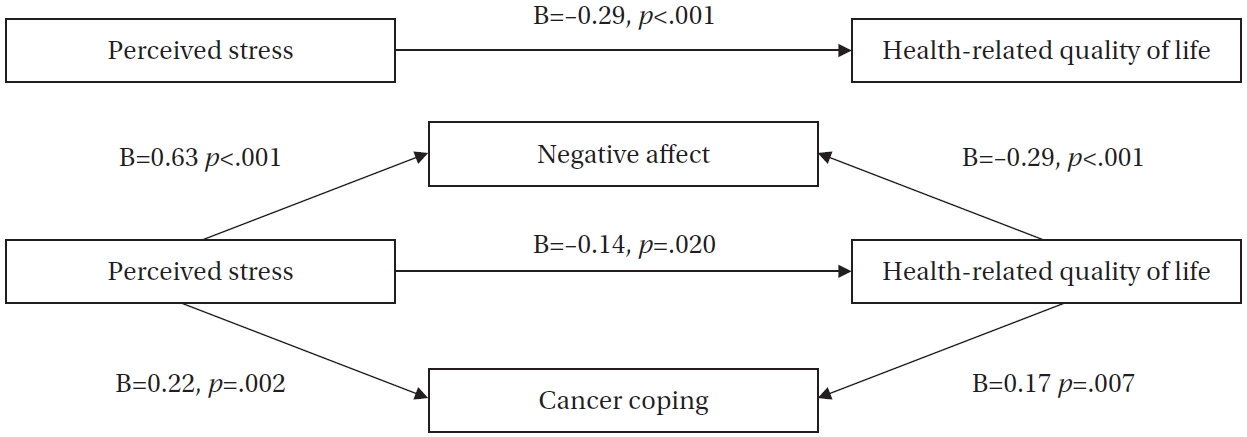

The mediation analysis using Hayes’ PROCESS macro confirmed significant mediating roles of negative affect and cancer coping in the relationship between perceived stress and HRQoL. The regression model demonstrated appropriate goodness-of-fit after controlling for covariates, including spouse status, religion, primary caregiver presence, housework or childcare burden, medical fee payment method, and cancer treatment modality.

Perceived stress significantly affected negative affect (B=0.63, p<.001), and negative affect affected HRQoL (B=–0.29, p<.001). Furthermore, perceived stress significantly affected cancer coping (B=0.22, p=.002), and cancer coping affected HRQoL (B=0.17, p=.007). Bootstrapping analysis demonstrated two significant indirect effects between perceived stress and HRQoL, with the mediating effects of negative affect and cancer coping (B=–0.18, 95% confidence interval=–0.27 to –0.11; B=0.04, 95% confidence interval=0.01 to 0.08). Therefore, hypotheses 2 (negative affect and cancer coping would influence HRQoL), 3 (perceived stress would influence HRQoL), and 4 (negative affect and cancer coping would mediate the relationship between perceived stress and HRQoL) were supported. The final model accounted for 41% of the variance in HRQoL (F=26.17, p<.001).

These results exhibited acceptable goodness-of-fit, with no multicollinearity between the independent variables (range of variance inflation factor=1.032–1.393), the presence of a normal distribution of residuals (Kolmogorov-Smirnov’s

p>.05), no autocorrelation (Durbin–Watson’s range: D

L<Durbin–Watson’s index<4-D

L), and the presence of equal variance (Breusch-Pagan test,

p>.05) (

Table 4,

Figure 1).

DISCUSSION

This study confirmed that lower perceived stress levels, fewer negative emotions, and stronger cancer coping skills are associated with better HRQoL among patients with gynecological cancer. Notably, the significant mediating effects of negative emotions and cancer coping on the relationship between perceived stress and HRQoL emphasize their critical roles in patient outcomes. These findings underline the importance of addressing both psychological states and coping mechanisms to enhance the quality of life in this patient population.

The mean HRQoL score observed in this study was 2.80, with subscale scores of 3.19 for physical well-being, 2.99 for functional well-being, 2.86 for emotional well-being, and 2.16 for social well-being. These results align with previous studies using the same measurement tool among gynecological cancer patients [

6]. HRQoL was notably lower among patients lacking a primary family caregiver, particularly within the social domain. This aligns with a systematic review identifying unmet support needs in gynecological cancer patients [

22]. Similarly, another study reported inadequate physical, psychological, and informational support for Korean women with gynecological cancer [

23]. In the Korean context, cultural norms promoting emotional suppression and traditional caregiving expectations of women may exacerbate perceived stress. Married women often feel anxious about burdening their spouses, while single women may hesitate to engage in relationships due to illness-related insecurities [

24].

Negative affect was strongly associated with poorer HRQoL in this study, consistent with prior research linking negative emotions to decreased quality of life in cancer patients [

19]. Additionally, higher negative affect was observed among patients facing greater treatment costs, highlighting the critical need for financial and emotional support interventions to improve patient outcomes [

25]. Besides financial considerations, cultural factors in Korean society may influence emotional responses and coping strategies. Specifically, the cultural tendency to suppress negative emotional expression could heighten perceived stress and depressive symptoms [

24]. Furthermore, religious beliefs demonstrated a complex relationship with emotional responses; patients identifying as religious experienced higher negative affect. This finding contrasts with systematic reviews that generally associate religious engagement with lower depression, anxiety, and improved life satisfaction [

26]. This discrepancy might reflect cultural variations in how religiosity influences coping with illness. Intrinsic religiosity tends to encourage positive reframing of stressful experiences, whereas extrinsic religiosity may foster self-blame and exacerbate emotional distress [

27]. Thus, culturally sensitive, faith-based psychological interventions tailored to patients’ beliefs could significantly improve emotional coping and overall quality of life.

The average perceived stress score in this study was 2.76 and negatively correlated with HRQoL. This score is lower compared to another study employing the same tool (3.08 among colorectal, lung, and breast cancer patients) [

28], potentially reflecting differences in disease severity, metastasis rates, or recurrence among more diverse cancer populations. Additionally, ovarian cancer patients reported significantly higher perceived stress compared to cervical cancer patients. This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating persistent emotional distress, fatigue, and physical function decline among ovarian cancer survivors, even during remission, which substantially affects their long-term quality of life [

29,

30]. Therefore, ongoing psychological support and targeted stress management interventions are particularly vital for ovarian cancer survivors to alleviate chronic psychological burdens and sustainably enhance their HRQoL.

The overall mean cancer coping score in this study was 2.28, with subscale scores of 2.35 for individual coping and 2.18 for interpersonal coping. These scores are lower than those reported in previous research among ovarian cancer survivors (overall coping=2.57, individual=2.63, interpersonal=2.46) [

7]. This discrepancy may result from differences in cancer types studied (cervical, endometrial, and ovarian cancer). Across various cultures, cancer patients frequently experience appearance changes, such as hair loss, and lifestyle adjustments that limit their social interactions. These effects might be more pronounced in Korean society due to significant sociocultural emphasis on appearance and interpersonal harmony [

24].

The present study found that negative affect and cancer coping significantly mediated the relationship between perceived stress and HRQoL. Previous research consistently emphasizes perceived stress and coping strategies’ pivotal roles in mediating stress-related health outcomes. For instance, Tungtong et al. [

10] showed that mindfulness promoted adaptive coping, enhanced positive affect via positive reappraisal, and reduced negative affect through decreased rumination. Yeh et al. [

13] also found acceptance coping mediated the stress–quality-of-life relationship among gynecological cancer survivors, reinforcing the importance of acceptance-based coping interventions.

Moreover, the current study revealed a stronger indirect effect through negative affect compared to cancer coping, suggesting emotional responses may have a more immediate and pronounced impact on quality-of-life outcomes. This aligns with prior studies emphasizing the central role of affective responses in stress adaptation, particularly among cancer populations coping with uncertainty [

4,

9]. Although cancer coping also played a meaningful mediating role, its relatively smaller effect might stem from individual differences in available coping resources or support systems. Examining both mediators concurrently provides a comprehensive understanding of the complex psychological mechanisms underlying HRQoL in gynecological cancer survivors. Thus, personalized interventions targeting emotional regulation and coping strategies could significantly enhance patients’ physical, emotional, functional, and social well-being. Nevertheless, the study’s cross-sectional design limits causal interpretations, and findings should be interpreted with caution. While the sample size was appropriately determined using G*Power for parallel multiple mediation analysis to detect medium-sized effects, future studies with larger and more diverse samples are recommended to improve generalizability. Additionally, convenience sampling from a single clinic potentially limits external validity.

CONCLUSION

This study demonstrated that negative affect and cancer coping significantly mediate the relationship between perceived stress and HRQoL among patients diagnosed with gynecological cancer. The findings highlight the critical importance of developing interventions that integrate perceived stress management, emotional regulation, and coping strategies to enhance patients’ overall quality of life. Future research employing longitudinal designs could provide deeper insights into the evolving relationships between stress, emotions, and coping mechanisms over time. Furthermore, practical intervention programs specifically targeting the reduction of negative emotions, particularly among emotionally vulnerable groups such as ovarian cancer survivors, should be developed and rigorously evaluated.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and design acquisition - YWK, SK, and HJP; analysis - YWK, SK, and HJP; interpretation of the data - HJP; and drafting or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content - YWK, SK, and HJP.

-

FUNDING

None.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the gynecological cancer patients who participated in this study.

This article is a revision of the first author's master's thesis (dissertation) from CHA University.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data can be obtained from the corresponding authors.

Figure 1.Mediating effects of negative affect and cancer coping in the relationship between perceived stress and health-related quality of life.

Table 1.Mean Scores of Perceived Stress, Negative Affect, Cancer Coping, and HRQoL (N=118)

|

Variables/Sub-dimensions |

Score range |

No. of items |

M±SD |

Range (min–max) |

Cronbach’s α |

Normality Shapiro-Wilk’s p

|

|

Perceived stress |

1–5 |

13 |

2.76±0.75 |

1.00–4.31 |

.89 |

.310 |

|

Negative affect |

1–5 |

10 |

2.19±0.85 |

1.00–4.80 |

.91 |

<.001 |

|

Cancer coping |

1–4 |

23 |

2.28±0.60 |

1.00–3.96 |

.94 |

.318 |

|

Individual |

1–4 |

14 |

2.35±0.61 |

1.00–4.00 |

.91 |

|

|

Interpersonal |

1–4 |

9 |

2.18±0.80 |

1.00–4.00 |

.94 |

|

|

HRQoL |

0–4 |

27 |

2.80±0.50 |

1.00–3.81 |

.86 |

.560 |

|

Physical |

0–4 |

7 |

3.19±0.75 |

1.00–4.00 |

.84 |

|

|

Social |

0–4 |

7 |

2.16±0.79 |

1.00–3.71 |

.80 |

|

|

Emotional |

0–4 |

6 |

2.86±0.78 |

1.00–4.00 |

.78 |

|

|

Functional |

0–4 |

7 |

2.99±0.69 |

1.00–4.00 |

.84 |

|

Table 2.Differences in Perceived Stress, Negative Affect, Cancer Coping, and HRQoL According to Participants’ Characteristics (N=118)

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

n (%) or M±SD |

Perceived stress |

Negative affect |

Cancer coping |

HRQoL |

|

M±SD |

z or x2 (p) |

M±SD |

z or x2 (p) |

M±SD |

z or x2 (p) |

M±SD |

z or x2 (p) |

|

Age (year) |

|

43.92±9.39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

18–39 |

38 (32.2) |

2.89±0.88 |

2.05 |

2.07±0.81 |

3.07 |

2.22±0.69 |

1.08 |

2.86±0.40 |

1.00 |

|

40–54 |

63 (53.4) |

2.72±0.68 |

(.359) |

2.17±0.88 |

(.215) |

2.31±0.54 |

(.582) |

2.78±0.53 |

(.608) |

|

≥55 |

17 (14.4) |

2.61±0.70 |

|

2.51±0.80 |

|

2.33±0.64 |

|

2.74±0.62 |

|

|

Spouse |

Yes |

80 (67.8) |

2.81±0.70 |

–0.97 |

2.24±0.89 |

–0.75 |

2.39±0.56 |

–3.26 |

2.80±0.48 |

–0.10 |

|

No |

38 (32.2) |

2.66±0.84 |

(.330) |

2.07±0.77 |

(.454) |

2.05±0.64 |

(.001) |

2.79±0.55 |

(.922) |

|

Primary family caregiver |

Yes |

100 (84.7) |

2.77±0.76 |

–0.23 |

2.16±0.85 |

–0.67 |

2.33±0.61 |

–2.35 |

2.86±0.48 |

–2.48 |

|

No |

18 (15.3) |

2.73±0.73 |

(.745) |

2.31±0.85 |

(.505) |

1.99±0.50 |

(.019) |

2.48±0.54 |

(.013) |

|

Educational level |

≤High school |

28 (23.7) |

2.68±0.69 |

–0.89 |

2.33±0.81 |

–1.17 |

2.16±0.66 |

–0.97 |

2.77±0.50 |

–0.22 |

|

≥College |

90 (76.3) |

2.79±0.77 |

(.374) |

2.14±0.86 |

(.241) |

2.32±0.58 |

(.333) |

2.81±0.51 |

(.825) |

|

Employment |

Yes |

92 (78.0) |

2.72±0.79 |

–1.15 |

2.15±0.87 |

–0.97 |

2.30±0.63 |

–0.35 |

2.83±0.50 |

–1.43 |

|

No |

26 (22.0) |

2.91±0.57 |

(.251) |

2.30±0.79 |

(.331) |

2.24±0.50 |

(.723) |

2.68±0.50 |

(.154) |

|

Religion |

Yes |

58 (49.2) |

2.86±0.70 |

–1.46 |

2.33±0.84 |

–1.97 |

2.34±0.58 |

–1.14 |

2.79±0.53 |

–0.31 |

|

No |

60 (50.8) |

2.66±0.79 |

(.144) |

2.04±0.84 |

(.049) |

2.22±0.62 |

(.256) |

2.81±0.50 |

(.757) |

|

Person who paid medical fees |

Patient herself |

83 (70.3) |

2.68±0.79 |

–1.55 |

2.08±0.80 |

–2.00 |

2.21±0.61 |

–1.67 |

2.80±0.50 |

–0.02 |

|

Others |

35 (29.7) |

2.94±0.61 |

(.120) |

2.43±0.92 |

(.045) |

2.45±0.56 |

(.094) |

2.80±0.51 |

(.981) |

|

Housework/childcare burdens |

Yes |

84 (71.2) |

2.72±0.79 |

–0.54 |

2.13±0.88 |

–1.44 |

2.22±0.62 |

–1.44 |

2.83±0.51 |

–1.13 |

|

No |

34 (28.8) |

2.86±0.63 |

(.590) |

2.32±0.76 |

(.150) |

2.43±0.55 |

(.151) |

2.72±0.48 |

(.260) |

|

Disease duration (month) |

|

39.41±29.83 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≤12 |

38 (32.2) |

2.81±0.90 |

0.15 |

2.29±0.95 |

1.02 |

2.23±0.51 |

0.77 |

2.69±0.50 |

1.36 |

|

13–60 |

63 (53.4) |

2.73±0.71 |

(.927) |

2.11±0.79 |

(.601) |

2.29±0.63 |

(.680) |

2.84±0.50 |

(.507) |

|

≥61 |

17 (14.4) |

2.80±0.68 |

|

2.36±0.95 |

|

2.35±0.66 |

|

2.79±0.53 |

|

|

Type of gynecologic cancer |

Endometriala

|

32 (27.1) |

2.84±0.78 |

10.51 |

3.81±0.80 |

0.56 |

2.31±0.52 |

0.60 |

2.80±0.48 |

0.89 |

|

Ovarianb

|

23 (19.5) |

3.16±0.65 |

(.005) |

3.74±0.77 |

(.756) |

2.22±0.46 |

(.742) |

2.70±0.52 |

(.642) |

|

Cervicalc

|

63 (53.4) |

2.57±0.71 |

b>c |

3.84±0.91 |

|

2.29±0.69 |

|

2.83±0.51 |

|

|

Treatment modality |

Single |

97 (82.2) |

2.70±0.80 |

–1.93 |

2.13±0.88 |

–1.90 |

2.24±0.64 |

–1.37 |

2.86±0.50 |

–3.04 |

|

Combination |

21 (17.8) |

3.01±0.41 |

(.054) |

2.45±0.68 |

(.058) |

2.45±0.35 |

(.171) |

2.50±0.37 |

(.002) |

Table 3.Relationship between Perceived Stress, Negative Affect, Cancer Coping, and HRQoL (N=118)

|

Variables |

Perceived stress |

Negative affect |

Cancer coping |

HRQoL |

|

r (p) |

|

Perceived stress |

- |

|

|

|

|

Negative affect |

.58 (<.001) |

- |

|

|

|

Cancer coping |

.23 (.012) |

.11 (.222) |

- |

|

|

HRQoL |

–.45 (<.001) |

–.59 (<.001) |

.12 (.191) |

- |

Table 4.Mediating Effects of Negative affect and Cancer Coping between Perceived Stress and HRQoL (N=118)

|

Variables |

Effect (B) |

SE |

t |

p

|

95% CI |

R2

|

F (p) |

|

Lower |

Upper |

|

Model of mediating variable (dependent variable: negative affect, M1) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Constant) |

0.44 |

.25 |

1.76 |

.082 |

–0.06 |

0.93 |

.31 |

52.76 (<.001) |

|

Perceived stress |

0.63 |

.08 |

7.26 |

<.001 |

0.46 |

0.71 |

|

|

|

Model of mediating variable (dependent variable: cancer coping, M2) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Constant) |

1.67 |

.20 |

8.17 |

<.001 |

1.27 |

2.08 |

.08 |

9.59 (.003) |

|

Perceived stress |

0.22 |

.07 |

3.10 |

.002 |

0.08 |

0.36 |

|

|

|

Model of mediating variable (dependent variable: HRQoL, Y) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(Constant) |

3.43 |

.18 |

19.53 |

<.001 |

3.09 |

3.78 |

.41 |

26.17 (<.001) |

|

Perceived stress |

–0.14 |

.06 |

–2.36 |

.020 |

–0.26 |

–0.02 |

|

|

|

Negative affect |

–0.29 |

.05 |

–5.67 |

<.001 |

–0.39 |

–0.19 |

|

|

|

Cancer coping |

0.17 |

.06 |

2.77 |

.007 |

0.05 |

0.30 |

|

|

|

Type |

Path |

Effect (B) |

SE |

T |

p

|

95% CI |

95% CI |

|

Lower |

Upper |

BootSE |

Boot lower |

Boot upper |

|

Indirect effect |

Total |

–0.15 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.05 |

–0.24 |

–0.06 |

|

X→M1→Y |

–0.18 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.04 |

–0.27 |

–0.11 |

|

X→M2→Y |

0.04 |

|

|

|

|

|

0.02 |

0.01 |

0.08 |

|

Direct effect |

X→Y |

–0.14 |

.06 |

–2.36 |

.020 |

–0.26 |

–0.02 |

|

|

|

|

Total effect |

X→Y |

–0.29 |

.06 |

–5.15 |

<.001 |

–0.40 |

–0.18 |

|

|

|

REFERENCES

- 1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229-63. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21834

- 2. National Cancer Information Center. 5-year relative survival rate [Internet]. Goyang: National Cancer Information Center; 2021 [cited 2024 November 18]. Available from: https://www.cancer.go.kr/lay1/S1T648C650/contents.do

- 3. Boa R, Grenman S. Psychosexual health in gynecologic cancer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;143 Suppl 2:147-52. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12623

- 4. Bae EJ, Lee SY, Jung HM. Impacts of symptom clusters, performance and emotional status on the quality of life of patients with gynecologic cancer. J Korean Soc Matern Child Health. 2019;23(1):45-55. https://doi.org/10.21896/jksmch.2019.23.1.45

- 5. Gil-Ibanez B, Davies-Oliveira J, Lopez G, Díaz-Feijoo B, Tejerizo-Garcia A, Sehouli J. Impact of gynecological cancers on health-related quality of life: historical context, measurement instruments, and current knowledge. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2023;33(11):1800-6. https://doi.org/10.1136/ijgc-2023-004804

- 6. Kim G, Kim M. Impacts of psychological distress, gender role attitude, and housekeeping sharing on quality of life of gynecologic cancer survivors. Korean J Women Health Nurs. 2018;24(3):287-96. https://doi.org/10.4069/kjwhn.2018.24.3.287

- 7. Oh JM, Kim Y, Kwak Y. Factors influencing posttraumatic growth in ovarian cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2021;29(4):2037-45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05704-6

- 8. Mazor M, Paul SM, Chesney MA, Chen LM, Smoot B, Topp K, et al. Perceived stress is associated with a higher symptom burden in cancer survivors. Cancer. 2019;125(24):4509-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32477

- 9. Folkman S, Lazarus RS. Coping as a mediator of emotion. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(3):466-75. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.466

- 10. Tungtong P, Ranchor AV, Schroevers MJ. Stress appraisal and emotion regulation mediate the association between mindfulness and affect in cancer patients: differential mechanisms for positive and negative affect. Psychooncology. 2023;32(10):1548-56. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.6201

- 11. Moorey S, Frampton M, Greer S. The Cancer Coping Questionnaire: a self-rating scale for measuring the impact of adjuvant psychological therapy on coping behaviour. Psychooncology. 2003;12(4):331-44. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.646

- 12. Forte AJ, Guliyeva G, McLeod H, Dabrh AMA, Salinas M, Avila FR, et al. The impact of optimism on cancer-related and postsurgical cancer pain: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2022;63(2):e203-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.09.008

- 13. Yeh YC, Kuo SF, Lu CH. The relationships between stress, coping strategies, and quality of life among gynecologic cancer survivors. Nurs Health Sci. 2023;25(4):636-45. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.13056

- 14. Spagnoletti BRM, Bennett LR, Keenan C, Shetty SS, Manderson L, McPake B, et al. What factors shape quality of life for women affected by gynaecological cancer in South, South East and East Asian countries? A critical review. Reprod Health. 2022;19(1):70. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-022-01369-y

- 15. Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. 2nd ed. New York: The Guilford Press; 2018.

- 16. Kang YS. A study on the awareness of stress due to hospitalization [master’s thesis]. Seoul: Yonsei University; 1984.

- 17. Volicer BJ, Bohannon MW. A hospital stress rating scale. Nurs Res. 1975;24(5):352-9.

- 18. Lee HH, Kim EJ, Lee MK. A validation study of Korea positive and negative affect schedule: the PANAS scales. Korean J Clin Psychol. 2003;22(4):935-46.

- 19. Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063-70. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063

- 20. Kim JN, Kwon JH, Kim SY, Yu BH, Hur JW. Validation of Korean-Cancer Coping Questionnaire (K-CCQ). Korean J Health Psychol. 2004;9(2):395-414.

- 21. Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11(3):570-9. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1993.11.3.570

- 22. Beesley VL, Alemayehu C, Webb PM. A systematic literature review of the prevalence of and risk factors for supportive care needs among women with gynaecological cancer and their caregivers. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(3):701-10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3971-6

- 23. Lee HJ, Kwon IG. Supportive care needs of patients with gynecologic cancer. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2018;18(1):21-9. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2018.18.1.21

- 24. Kim SJ, Shin H. The experience of gynecologic cancer in young women: a qualitative study. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2023;53(1):115-28. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.22119

- 25. Rhee YS, Kim SY, Park JH. Financial hardship factors affecting the cancer patient's quality of life. J Korea Acad Ind Coop Soc. 2020;21(10):299-307. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2020.21.10.299

- 26. Snider AM, McPhedran S. Religiosity, spirituality, mental health, and mental health treatment outcomes in Australia: a systematic literature review. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2014;17(6):568-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2013.871240

- 27. Kim HB, Seol KO. Religious orientation and anxiety: negative affect and self-regulation as mediators. Korean J Couns Psychother. 2015;27(2):383-403.

- 28. Kim EJ, Han JW. the effects of stress and stress coping on life quality in cancer patients and caregivers: a dyadic analysis using an actor-partner interdependence model. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2018;18(3):135-42. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2018.18.3.135

- 29. Dinapoli L, Colloca G, Di Capua B, Valentini V. Psychological aspects to consider in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment. Curr Oncol Rep. 2021;23(3):38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-021-01049-3

- 30. Bhat G, Karakasis K, Oza AM. Measuring quality of life in ovarian cancer clinical trials: can we improve objectivity and cross trial comparisons? Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(11):3296. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12113296