Abstract

-

Purpose

This review aimed to analyze the use of behavior change techniques (BCTs) and the degree of theory implementation using a theory coding scheme (TCS) in mobile self-management interventions for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

-

Methods

In this scoping review, four electronic databases (PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, and CENTRAL) and gray literature sources were searched. Studies were independently screened according to predefined criteria. The BCT taxonomy was used to categorize techniques, and the TCS was applied to evaluate the quality of theory implementation.

-

Results

Seventeen randomized controlled trials were included. Twenty-five unique BCTs were identified (mean, 8.1 per study). Commonly used BCTs included social support (unspecified) (n=14), instructions on how to perform a behavior (n=14), feedback on behavior (n=11), and prompts/cues (n=11). Techniques related to capability, such as habit formation, rewards, framing/reframing, and verbal persuasion, were rare (n=1 study each). TCS scores ranged from 5 to 15 (mean, 10.3). All included studies cited a theory, used it to select intervention techniques, and employed randomization. However, no study used the findings to refine the theory, and only one conducted a mediational analysis of theoretical constructs.

-

Conclusion

Mobile T2DM self-management interventions commonly rely on a limited range of BCTs and show restricted theoretical application beyond basic implementation. Future interventions should employ a broader array of BCTs and apply theories more rigorously, including tailoring interventions, empirically testing theoretical mechanisms, and refining theories based on results to increase their effectiveness.

-

Key Words: Diabetes mellitus, type 2; Health behavior; Mobile applications; Self-management

INTRODUCTION

The global prevalence and mortality of diabetes mellitus have been steadily increasing [

1]. As of 2022, approximately 828 million people worldwide were living with diabetes—a nearly four-fold increase since 1990—with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) accounting for over 90% of all cases [

2]. In South Korea, the prevalence of T2DM among adults aged ≥30 years increased consistently over 25 years, rising from 6.71% during 1998–2005 to 15.61% during 2020–2022 [

1]. Moreover, global diabetes-related mortality among adults aged 20 to 79 years was estimated at approximately 3.4 million in 2024 [

3]. In South Korea, the mortality rate for diabetes mellitus in 2023 was 21.6 per 100,000 population, ranking it as the seventh leading cause of death [

4].

Elevated blood glucose levels due to diabetes substantially increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases, including peripheral vascular and coronary artery disease [

5,

6]. Inadequate self-management behaviors, such as poor medication adherence or inconsistent blood glucose monitoring, can result in severe complications, including blindness, myocardial infarction, stroke, and peripheral vascular disease [

6]. Therefore, individuals with diabetes must engage in comprehensive self-management to effectively control their condition and prevent complications [

7,

8]. In this context, self-management refers to the range of daily activities that patients undertake to regulate their condition and prevent long-term complications. These activities encompass lifestyle behaviors such as maintaining a healthy diet and regular exercise, as well as essential clinical tasks like medication adherence and self-monitoring of blood glucose levels [

6].

Recent advances in information and communication technology (ICT) have facilitated the development of various mobile tools—including mobile applications, text messaging, and web-based platforms—that support self-management among patients [

9]. These mobile technologies assist patients by recording and visualizing data on blood glucose, medication adherence, weight, diet, and exercise, while providing real-time feedback and specific guidance based on user input [

10]. Consequently, these technologies have been shown to improve glycemic control and strengthen overall self-management capabilities, yielding positive outcomes for diabetes care [

10,

11].

Although mobile interventions offer valuable support for diabetes self-management, their effectiveness depends on a systematic, theory-based design to promote sustained behavior change [

12]. However, many existing mobile interventions only reference theoretical models superficially, demonstrating wide variation in the degree of theoretical application across studies and often lacking clear links between intervention components and theoretical constructs [

13]. As the mere mention of theory does not ensure intervention effectiveness, there remains a pressing need to identify which theoretical approaches and behavior change strategies underpin effective mobile interventions [

14].

To objectively assess discrepancies in theoretical application and potential limitations in behavior change strategies—and to identify effective intervention components—standardized tools are needed to evaluate theory-based interventions systematically. The behavior change technique (BCT) taxonomy is particularly useful for identifying and categorizing specific behavioral techniques applied to T2DM management in order to determine the effective elements [

15]. In contrast, the theory coding scheme (TCS) evaluates the extent to which theoretical frameworks are faithfully and systematically applied during intervention design and evaluation [

16]. Therefore, by using these taxonomies, it is possible to determine which BCTs are most frequently employed and how thoroughly theories are implemented in mobile interventions for patients with T2DM.

Scoping reviews can examine the available evidence within a given field, identify knowledge gaps that often precede systematic reviews, and synthesize information to provide a comprehensive overview of broad topics [

17]. In particular, theory-based mobile interventions for patients with T2DM exhibit considerable heterogeneity, with wide variations in the applied theories, technologies, and intervention components. Although prior meta-analyses have investigated these interventions, their analyses of the theoretical underpinnings have been limited [

10,

17]. For example, some have focused on the effectiveness of BCTs while including participants with type 1 diabetes, whereas others have merely identified whether a theory was mentioned in the study without systematically assessing its quality or fidelity. In a heterogeneous field where the primary knowledge gap concerns the application of theory rather than its effectiveness, a scoping review represents the most appropriate methodological approach [

18]. Therefore, while previous studies have primarily emphasized the effectiveness of mobile interventions, this review systematically evaluates the application of BCTs and the fidelity of theoretical implementation to provide guidance for more effective and practical interventions.

Accordingly, this study employed a scoping review methodology to comprehensively examine theory-based mobile self-management interventions for patients with T2DM. The primary objectives were to identify and analyze the BCTs applied within these interventions and to evaluate the degree of theoretical implementation fidelity across the included studies. This analysis aims to enhance the health outcomes of patients with T2DM by clarifying the current status of theory-based mobile interventions for diabetes self-management and by offering practical directions for future research and clinical application.

METHODS

1. Study Design

The methods used in this review were based on Arksey and O’Malley’s five-step framework for scoping reviews [

19]. The procedure consisted of the following stages: (1) identifying the research question, (2) identifying relevant studies, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, and (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. This review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping reviews [

20]. The protocol was registered in the Open Science Framework (

https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/VFD3J). Consistent with scoping review methodology, the methodological quality of the included studies was not critically appraised [

19].

For scoping reviews, research questions should be broad enough to allow comprehensive exploration while remaining specific and clearly defined [

17]. The research questions for this review were as follows: “What are the characteristics of theory-based mobile self-management intervention studies for patients with T2DM?”, “What behavior change techniques are applied to theory-based mobile self-management interventions?”, “How have these theories been implemented in studies applying theory-based mobile self-management interventions?”

The literature search was conducted from November 1, 2024, to November 8, 2024. To ensure a comprehensive search and capture all relevant studies regardless of publication date, no publication year restrictions were applied. Searches were performed in four electronic databases: PubMed, EMBASE, the Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). In PubMed, Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were used as the controlled vocabulary, while in EMBASE, Elsevier’s life science thesaurus (Emtree) was employed. The search strategy combined key terms representing “type 2 diabetes mellitus” (participants) and “mobile self-management interventions” (intervention). Keywords were adapted for each database using controlled vocabularies, Boolean operators, and truncation searches. In addition to online database searches, a manual search was conducted through Google Scholar to identify gray literature (

Supplementary Data 1).

Following scoping review methodology [

19] and after removing duplicate records, two authors independently screened all studies according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements during study selection were resolved through joint review and discussion of the full texts. The inclusion criterion was a theory-based mobile self-management intervention targeting patients with T2DM. To be considered “theory-based,” a study had to explicitly mention at least one theoretical framework used to guide the intervention’s design or content. Studies that did not specify any theoretical foundation were excluded. Additional exclusion criteria included commentaries, case reports, and unpublished works such as conference abstracts or posters, as well as studies unrelated to the research questions. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included. RCTs were selected because, as a rigorous study design, they typically provide detailed descriptions of intervention components and their theoretical rationale—information essential for extracting high-quality data for the BCT and TCS analyses. Ultimately, 17 articles met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed (

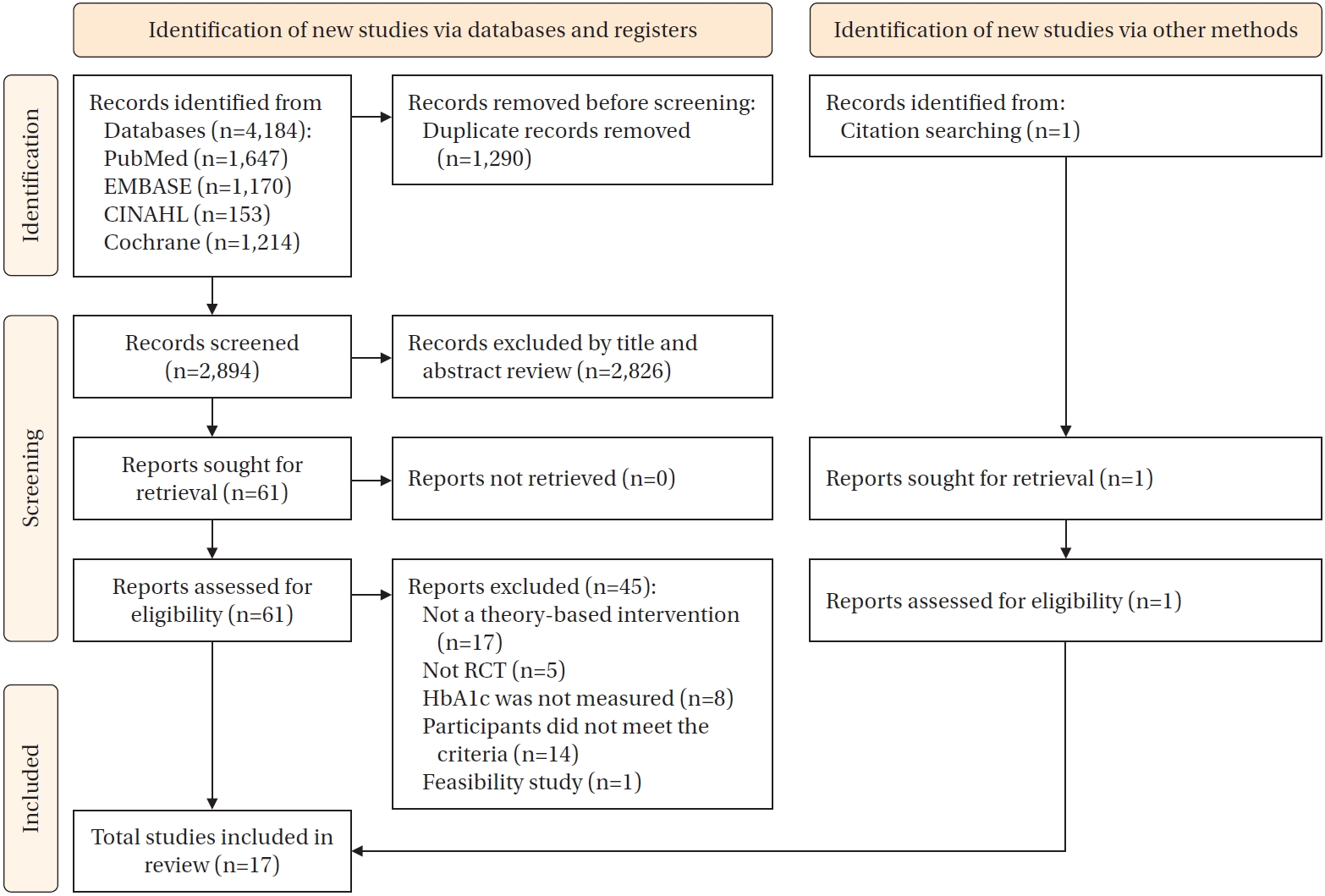

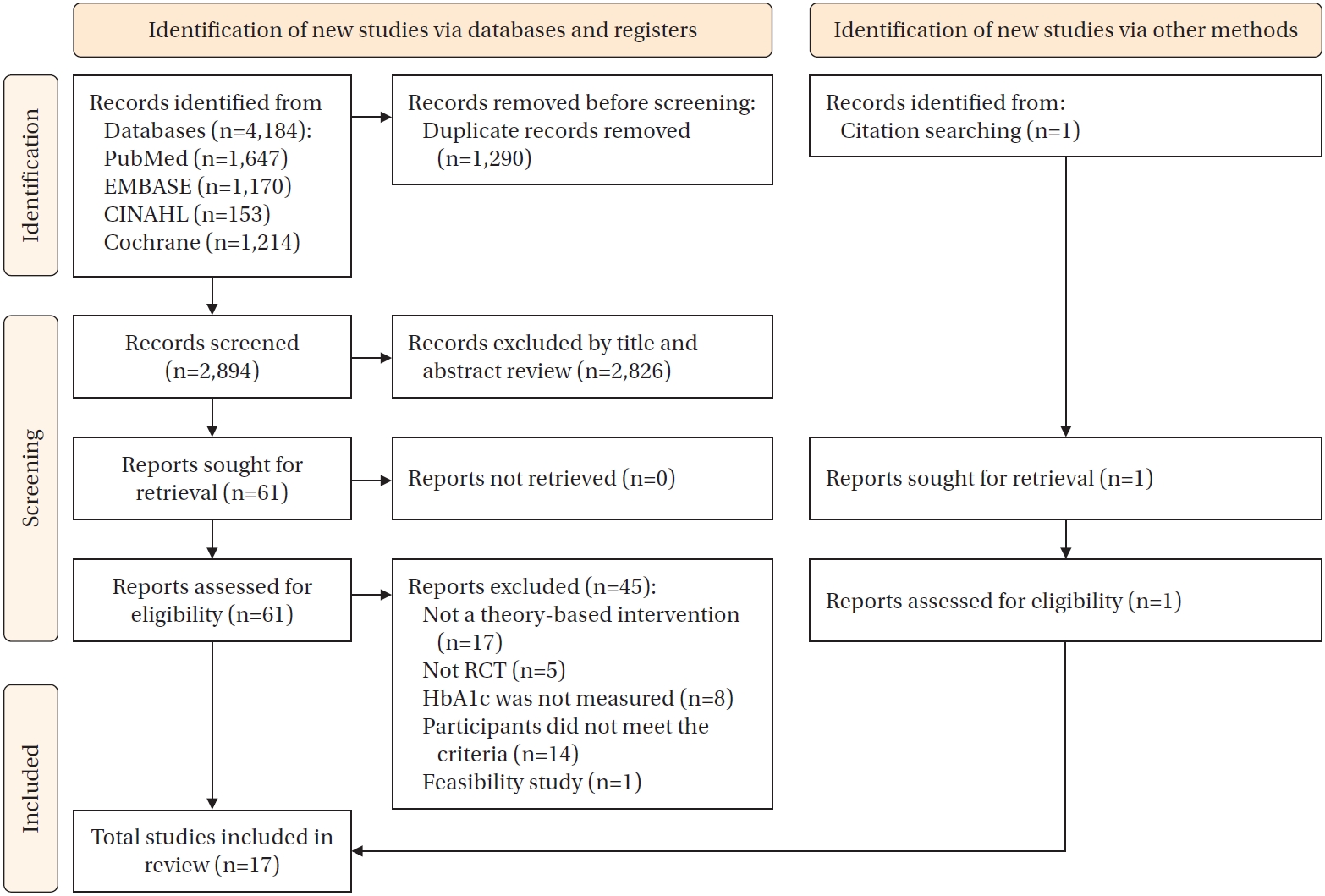

Figure 1).

For data charting, EndNote 21 (Clarivate, Philadelphia, PA, USA) a reference management software, was used to review and organize the literature. An Excel template (ver, 2018; Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), developed by the researchers through discussions during research meetings, served as the standardized format for data charting. Data extraction, including the identification and classification of BCTs and TCS items, was primarily performed by one author (HM). The coding process for BCTs followed the BCT taxonomy manual, while TCS scoring adhered to the guidelines established by Michie and Prestwich [

16]. To ensure consistency in the interpretation of each item and technique, detailed internal coding guidelines were developed and utilized for both BCT and TCS coding. Another author (SKH) independently reviewed and verified all extracted data and coded items, with special attention to areas requiring clarification, subjective interpretation, or potential inconsistencies. Any discrepancies or issues requiring further deliberation were resolved through iterative discussions and consensus-building during research meetings. This process involved re-examining the original study texts and re-evaluating the application of the coding guidelines until full agreement was reached between the two researchers, thereby ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the charted data.

The extracted data were analyzed to identify the characteristics of the intervention studies, the specific BCTs employed, their frequency, and the extent of theoretical implementation.

The data extraction form for analyzing study characteristics included the following variables: authors, publication year, country, number of participants, theoretical framework, intervention characteristics (delivery methods, content, duration, and frequency), and primary study outcomes.

For the identification and coding of behavior change techniques, the BCT taxonomy [

15] was applied. BCTs are specific strategies designed to facilitate behavior change and are classified into 16 categories encompassing 93 distinct techniques. Each specific BCT and its frequency of application within the selected interventions were analyzed to determine overall trends and utilization patterns.

To systematically analyze the extent of theory implementation and the characteristics of each theoretical category across the intervention studies, the TCS developed by Michie and Prestwich [

16] was used. The TCS is a 19-item tool that systematically evaluates how explicitly a theory is employed, how intervention components are linked to theoretical constructs, and how the theory is integrated into the design and evaluation processes. The TCS items are grouped into six categories: (1) reference to underpinning theory (items 1, 2, 3); (2) targeting of relevant theoretical constructs (items 2, 5, 7–11); (3) using theory to select recipients or tailor interventions (items 4, 6); (4) measurement of constructs (items 12, 13); (5) testing of mediation effects (items 12–18); and (6) refining theory (item 19). Each item was rated as “yes” (1 point), “no” (0 points), or “do not know” (0 points). To ensure the reliability of TCS coding, the primary researcher (HM) conducted the initial scoring for all included studies, after which a second researcher (SKH) independently verified all coded items against the original articles. Any discrepancies identified during this verification process were resolved through consensus-based discussion between the two researchers. The final TCS scores used for analysis reflected this consensus, ensuring consistent and reliable evaluation of theory application.

RESULTS

1. Characteristics of the Included Studies

The general characteristics of the 17 theory-based mobile self-management intervention studies for patients with T2DM included in this review are summarized in

Supplementary Data 2, with specific details presented in

Table 1. The full list of the reviewed articles is provided in

Supplementary Data 3. Regarding publication year, nine studies [A1-9] were published after 2020, six [A10-15] between 2015 and 2019, and two [A16,A17] before 2015. The studies were conducted in various countries, with South Korea contributing three [A3,A4,A10]; the United States [A11,A17], China [A2,A13], and Malaysia [A6,A14] contributing two each. The number of participants per study varied: fewer than 100 in seven studies [A2,A4,A6,A9,A10,A15,A16]; between 100 and 199 in six [A1,A3,A8,A11,A13,A14]; and 200 or more in four [A5,A7,A12,A17]. The most frequently employed theoretical frameworks were the transtheoretical model (TTM) [A1,A11,A13,A14] and the information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) model [A3,A9,A10,A16], each applied in four studies. These were followed by the health belief model (HBM) [A11,A15], social cognitive theory [A8,A17], theory of planned behavior (TPB) [A13,A15], and individual and family self-management theory [A2,A6], each used in two studies (11.8%). Two studies employed multiple theoretical frameworks: Benson et al. [A11] combined the HBM with the TTM, while Kleinman et al. [A15] integrated the HBM, TPB, health action process approach, and self-efficacy theory. Regarding delivery methods, mobile applications were most commonly used (10 studies) [A3-6,A8,A10,A12,A13,A15,A16], followed by telephone counseling (6 studies) [A1-3,A9-11]. The most frequent intervention components included information provision for diabetes self-management education (13 studies) [A1-9,A11-14], self-monitoring of health behaviors (10 studies) [A1,A3-6,A8,A10,A13,A15,A16], individualized feedback on behavioral changes (9 studies) [A1-4,A8-10,A16,A17], and behavioral reminders (7 studies) [A3,A5,A6,A9,A12,A14,A15]. Intervention durations ranged from 5 weeks to 5 years: two studies [A6,A10] lasted less than 3 months; four [A2-4,A9] lasted 3–6 months; five [A7,A8,A12,A15,A16] lasted 6–12 months; and six [A1,A5,A11,A13,A14,A17] lasted 12 months or longer. The main clinical indicator assessed was hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), measured in 16 studies [A1-5,A7-17]. Key self-management indicators included self-care activities such as diet, exercise, medication adherence, and blood glucose monitoring, evaluated in 12 studies [A1-5,A8-10,A12,A13,A15,A17]. For psychosocial indicators, self-efficacy was the most frequently assessed variable, appearing in eight studies [A1-4,A8-10,A15].

The frequency and types of BCTs applied in the theory-based mobile self-management interventions are summarized in

Table 2. Across the 17 studies, a total of 25 distinct BCTs were identified, with each study employing between five and 13 techniques (mean=8.1 per study). The most frequently applied BCTs were social support (unspecified) (3.1) [A1-10,A13,A15-17] and instruction on how to perform the behavior (4.1) [A2-14,A17], each used in 14 studies. These were followed by feedback on behavior (2.2) [A1,A3-5,A8-10,A13-16] and prompts/cues (7.1) [A3-7,A10,A11,A13-16], both used in 11 studies, and goal setting (behavior) (1.1) [A1,A2,A4,A5,A9,A12-14,A16,A17], used in 10. Conversely, the least frequently used techniques were habit formation (8.3) [A5], material reward (behavior) (10.2) [A7], non-specific reward (10.3) [A4], framing/reframing (13.2) [A12], and verbal persuasion about capability (15.1) [A1], each applied in only one study.

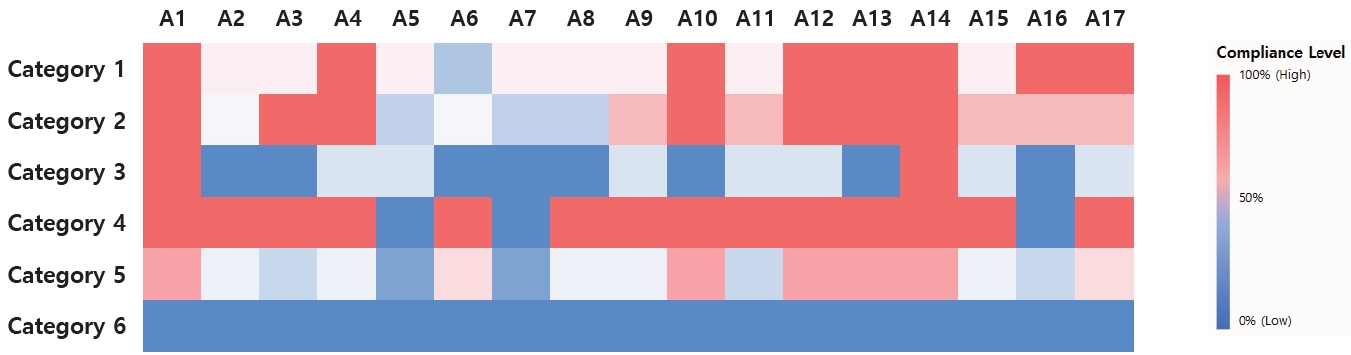

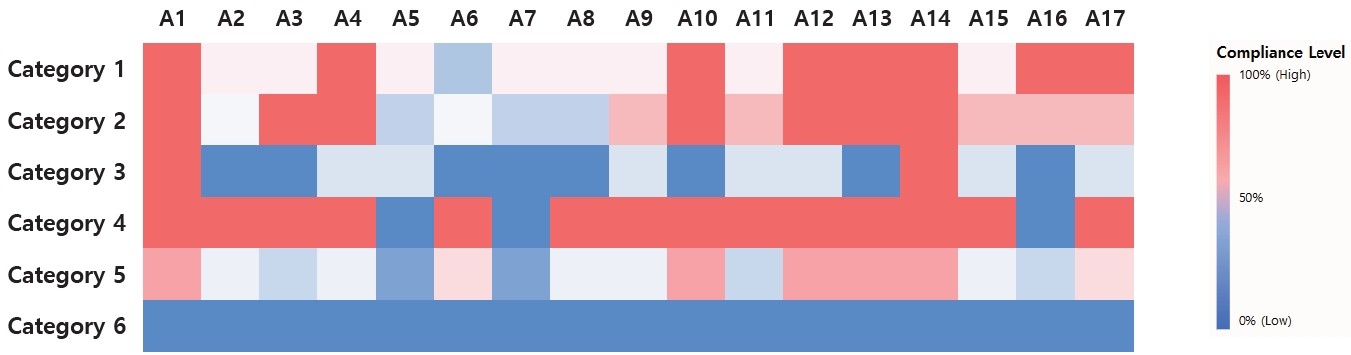

The results of the TCS evaluation are presented in

Table 3 and

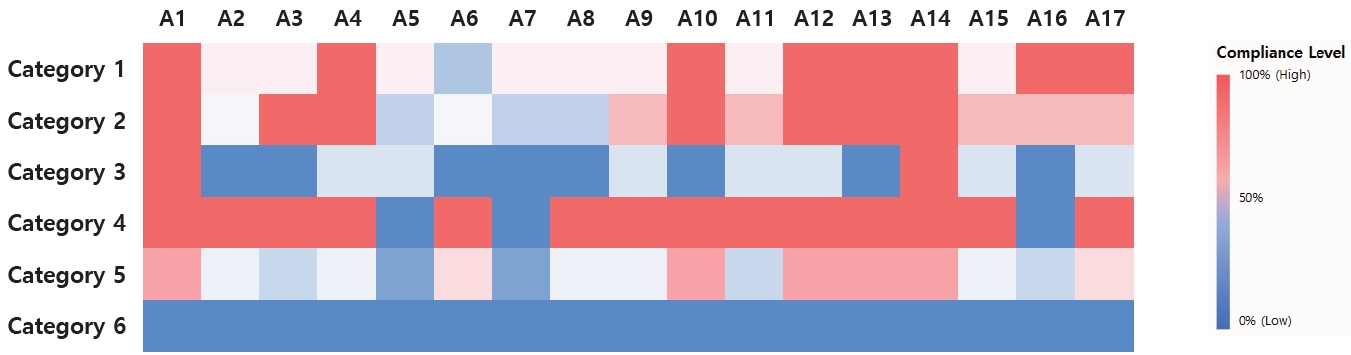

Figure 2. Across the 19 TCS items, total scores ranged from 5 to 15, with a mean score of 10.3. One study achieved a score ≥15, eight studies scored between 10–14, and the remaining eight scored ≤9. Among individual items, “theory of behavior mentioned,” “theory used to select intervention techniques,” and “randomization of participants to condition” were satisfied in all 17 studies. In contrast, “targeted construct mentioned as predictor of behavior” [A1-5,A9-17], “theory-relevant constructs are measured” [A1-4,A6,A8-15,A17], and “quality of measures” [A1-4,A6,A8-15,A17] were fulfilled in 14 studies. However, “results used to refine theory” and “mediational analysis of constructs” were satisfied in zero and one study [A17], respectively, indicating poor adherence to these advanced theoretical applications.

Analysis of the six main categories of the TCS revealed consistent patterns across the included studies. Category 1, which evaluated whether a theory was explicitly mentioned, showed generally high levels of application across all 17 studies. Studies A1, A4, A10, A12–14, A16, and A17 demonstrated particularly strong theoretical utilization, with scores exceeding 80%, whereas study A6 showed limited use with a score below 40%. Category 2, which assessed the linkage between intervention techniques and theoretical constructs, also demonstrated high connectivity in studies A1, A3, A4, and A9–17, all scoring above 80%, while studies A5–A8 scored below 40%, indicating weaker connections. Category 3, which examined the use of theory to guide participant selection and intervention tailoring, exhibited high application only in studies A1 and A14, both with 100% scores, while most other studies applied theory minimally in this respect. Category 4, which assessed the measurement of theoretical constructs and the quality of measurement tools, showed the highest overall level of theory application, with most studies achieving perfect scores; however, studies A5, A7, and A16 received 0%, reflecting inadequate construct measurement. In Category 5, which evaluated theoretical verification of intervention effects, studies A1, A10, and A12–A14 displayed strong verification with scores above 80%, whereas many others showed moderate verification at 40% to 60%, and studies A5 and A7 scored below 40%, indicating weak verification. Finally, Category 6, which assessed whether research findings were used to refine or further develop theory, revealed no evidence of theoretical advancement in any of the included studies.

DISCUSSION

This study analyzed the BCTs used in theory-based mobile self-management interventions for patients T2DM and evaluated the degree of theoretical implementation using a scoping review methodology. Based on these findings, the following discussion addresses the characteristics of the interventions, the application of BCTs, and the extent of theoretical implementation.

Among the 17 studies analyzed, 9 (52.9%) were published after 2020, reflecting the growing research interest in this field and its expansion driven by the rapid development of ICT and increasing evidence for the effectiveness of mobile interventions [

9]. The most frequently applied theoretical frameworks were the TTM and the IMB model, each used in four studies (23.5%), consistent with previous findings showing that TTM is the most commonly adopted framework in mobile-based diabetes self-management interventions [

21]. TTM enhances self-management effectiveness by offering stage-matched, tailored interventions and relapse-prevention strategies. When integrated with mobile technologies that enable real-time data collection and analysis, TTM facilitates interventions optimized to the participant’s stage of behavioral change [

21]. Likewise, the IMB model structures and applies three core components—information, motivation, and behavioral skills—in a systematic manner. Mobile interventions based on the IMB model have demonstrated lower dropout rates compared to traditional face-to-face programs and have proven highly effective in promoting sustained self-management behaviors [

22]. Both theoretical frameworks thus demonstrate strong conceptual and empirical foundations, and their high utilization in this review aligns with previous evidence of their effectiveness in enhancing mobile intervention outcomes.

Mobile applications were the predominant mode of intervention delivery, employed in 10 studies, valued for their practicality, accessibility, and sustainability, enabling self-management without temporal or spatial constraints [

10]. The most frequently implemented intervention components included information provision related to diabetes self-management education (13 studies), self-monitoring (10 studies), and personalized feedback (9 studies). Systematic reviews of face-to-face self-management education programs for patients with T2DM have primarily focused on core educational elements such as exercise, nutrition, medication adherence, blood glucose monitoring, smoking cessation, cardiovascular risk reduction, and diabetes complication prevention [

23]. While mobile interventions share similar educational foundations, they additionally leverage technological advantages, overcoming spatiotemporal barriers through real-time data collection and personalized feedback delivery [

24]. Through these capabilities, mobile interventions have consistently been shown to improve glycemic control, self-management behaviors, and self-efficacy [

25]. These findings suggest that reductions in HbA1c achieved through mobile interventions are not only clinically meaningful in preventing long-term complications but also indicate their potential as practical strategies in nursing practice to enhance patients’ self-directed management and sustain healthy behaviors.

Across the 17 studies, 25 distinct BCTs were identified, with an average of 8.1 per study. The most frequently used techniques were social support (unspecified) and instruction on how to perform the behavior, mirroring patterns observed in prior analyses of interventions targeting patients with obstructive sleep apnea [

26]. These findings underscore the central role of knowledge provision and social support in driving behavior change. Cognitive support through education [

27] and emotional and practical reinforcement through social support [

28] are both essential and complementary components of behavioral change. However, the exposure technique, which was frequently employed in Cho and Hwang’s study [

26], was rarely used here, likely reflecting differences in target behaviors and disease-specific challenges. Whereas exposure techniques may address procedural anxiety in treatments such as continuous positive airway pressure therapy, the interventions analyzed in this review primarily focused on long-term lifestyle modification. Additionally, habit formation, material reward (behavior), non-specific reward, framing/reframing, and verbal persuasion about capability were each identified in only one study, indicating low utilization. This limited use may reflect practical constraints such as short study durations and challenges in implementing highly personalized approaches, leading researchers to prioritize techniques with more immediate outcomes. Nevertheless, these BCTs are crucial for fostering long-term adherence through reinforcement, intrinsic motivation, and positive cognitive restructuring during early behavior change stages [

15]. Future intervention research should address these practical barriers and incorporate such techniques more effectively to promote sustained behavior change.

Although this review did not directly assess the relationship between specific BCTs and intervention effectiveness, prior evidence suggests that interventions employing a greater variety of BCTs tend to achieve stronger outcomes [

29]. By explicitly targeting the determinants of key health behaviors, BCTs help patients achieve and maintain desired outcomes in daily life [

30]. Therefore, applying a more integrated set of BCTs is essential for developing effective theory-based mobile self-management interventions.

Analysis using the TCS revealed theory implementation scores ranging from 5 to 15 (mean=10.3), indicating substantial variability among studies. This distribution is comparable to that reported by Timlin et al. [

31] (range=7–16, mean=11.2), suggesting that while theoretical frameworks are often cited, their comprehensive and systematic application remains limited. Although most studies demonstrated basic theoretical integration and methodological rigor, none advanced to the critical step of using empirical results to refine theory—a notable deficiency in iterative theory development. Consistent with observations by Patton et al. [

14], who highlighted unclear rationales and insufficient theoretical depth in many intervention studies, our findings indicate that while theoretical frameworks are frequently acknowledged, empirical testing and theory refinement remain underdeveloped.

Analysis by TCS category revealed high implementation fidelity for mentioning theory (Category 1) and measuring constructs (Category 4), and generally high fidelity for establishing relevance between constructs and intervention techniques (Category 2). In contrast, adherence was very low for using theory to select recipients or tailor interventions (Category 3) and for refining theory based on results (Category 6), while testing mediation effects (Category 5) showed high implementation in only a few studies [A1,A10,A12-14] and moderate to low implementation in the remaining studies. These findings—particularly the low adherence to tailoring and refinement—closely mirror those reported by Timlin et al. [

31]. Thus, while the studies demonstrated reasonable fidelity in the initial application of theory (e.g., specifying theoretical frameworks, linking them to intervention elements, and measuring relevant constructs), a critical limitation was evident in the later stages of theoretical application. Based on the TCS analysis, most researchers focused primarily on the early phases of theoretical implementation but did not extend their efforts to dynamic, iterative applications involving empirical validation, participant-specific tailoring, or theory refinement based on findings. This gap underscores the disconnection between empirical outcomes and theoretical advancement. To bridge this divide, future research must move beyond mere theoretical application and actively incorporate rigorous testing and iterative model refinement based on empirical evidence. Such integration is essential for advancing nursing science and improving the practical effectiveness and clinical relevance of digital interventions, ultimately contributing to higher research quality.

This study has several limitations that indicate specific directions for future research. First, its exclusive focus on RCTs may limit generalizability to real-world settings. Although RCTs demonstrate efficacy under controlled conditions, they often fail to reflect the complexity of clinical environments, where patients with chronic conditions face multiple, interacting challenges. Therefore, future studies should adopt more diverse research designs, such as pragmatic trials or mixed-methods approaches, to better capture the practical effectiveness of mobile interventions. Second, this study did not examine which specific intervention components—such as particular BCTs or levels of theoretical implementation—are most effective. Accordingly, further quantitative research, including meta-analyses and meta-regressions, is needed to determine which elements most strongly predict successful outcomes. Despite these limitations, this study makes meaningful contributions. Academically, it provides a comprehensive overview of the current state of theory-based mobile interventions and offers empirical insights through systematic classification using BCT and TCS frameworks. Clinically, the findings deliver practical guidance for strategically applying specific BCTs and tailoring interventions according to theoretical models. Building on these results, future research should focus on standardizing design and evaluation guidelines that promote the integration of diverse BCTs and the deeper, theory-informed customization of interventions. Such efforts will enhance the quality of mobile self-management programs, improve patient engagement, and ultimately reduce diabetes-related complications.

CONCLUSION

This scoping review identified the major characteristics and emerging trends of theory-based mobile self-management interventions for patients with T2DM. The TTM and the IMB model were the most frequently used theoretical foundations. Core intervention components commonly included information provision, diabetes self-management education, self-monitoring, and feedback. HbA1c and self-management behaviors were the primary outcome measures across studies. Regarding BCT utilization, social support (unspecified), instruction on how to perform the behavior, feedback on behavior, and prompts/cues were the most frequently applied techniques, while those specifically targeting motivation and habit formation were used far less often. Considerable variation was also observed in the degree of theory implementation. Although the foundational application of theory—such as specifying frameworks and using them to guide intervention development—was relatively well executed, the deeper application involving empirical testing or theoretical advancement was notably lacking.

Based on these findings, several recommendations are proposed. Future theory-based mobile interventions should adopt a more comprehensive and integrative use of BCTs, with greater emphasis on strategies that foster long-term behavior change, such as habit formation and motivational enhancement. Research should also systematically examine the relationships between specific BCTs and intervention effectiveness, as well as between theoretical fidelity and health outcomes. Finally, rather than merely referencing theoretical frameworks, future studies should employ diverse research designs that empirically test, validate, and refine these theories.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Conceptualization and methodology - HM and SKH; validation - SKH; formal analysis - HM and SKH; investigation and data curation - HM; drafting or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content - HM and SKH; visualization - HM and SKH; and supervision - SKH.

-

FUNDING

This work was supported by a 2-Year Research Grant of Pusan National University.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

None.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data can be obtained from the Supplementary Material.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Figure 1.Flow diagram of study selection. HbA1c=hemoglobin A1c; RCT=randomized controlled trial.

Figure 2.Heat map of theory implementation levels based on the six categories of the theory coding scheme. Category 1=reference to underpinning theory; Category 2=targeting of relevant theoretical constructs; Category 3=using theory to select recipients or tailor interventions; Category 4=measurement of constructs; Category 5=testing of mediation effect; Category 6=refining theory.

Table 1.Descriptive Summary of Included Studies

|

Author (year), country |

Participants |

Theoretical basis |

Intervention |

Comparison |

Outcomes |

|

Platform |

Content |

Duration (frequency) |

Clinical indicators |

Self-management indicator |

Psychosocial indicator |

|

Dunker et al. (2024), Germany [A1] |

I: 86, |

TTM |

Phone call |

Self-management education |

48 weeks (1–12 weeks: once/month, 13–48 weeks: once/3 months) |

Usual care |

HbA1c*

|

Self-care activity*

|

Self-efficacy*

|

|

C: 65 |

Self-monitoring and recording |

Quality of life |

|

Feedback |

|

Motivational interviewing |

|

Hu et al. (2024), China [A2] |

I: 11, |

IFSMT |

Video, phone call |

Self-management education |

12 weeks (video content: twice/week, phone call: biweekly) |

Usual care |

HbA1c |

Self-care activity |

Self-efficacy |

|

C: 12 |

Feedback via phone call |

BW |

Dietary intake |

Social support |

|

Sharing the goals with families/friends participants |

- Fruits |

Distress |

|

- Vegetable |

|

- Refined grains |

|

- Whole wheat |

|

- Sugary drinks |

|

- Starchy |

|

PA (MET) |

|

Park et al. (2024), South Korea [A3] |

I: 53, |

IMB |

App, phone call |

Self-management education |

12 weeks (app: daily, phone call: biweekly) |

Usual care |

HbA1c*

|

Self-care activity |

Self-efficacy |

|

C: 52 |

Self-monitoring and recording |

Quality of life |

|

Reminders |

|

Feedback via phone call |

|

Park et al. (2024), South Korea [A4] |

I: 19, |

Self-regulation theory |

App |

Self-management education |

12 weeks (daily) |

Usual care |

HbA1c*

|

Self-care activity |

Self-efficacy |

|

C: 13 |

Goal setting |

BG |

- General diet |

Quality of life |

|

Self-monitoring and recording |

LDL-cholesterol |

- Specific diet |

Depression |

|

Feedback |

- Exercise |

|

Communication via automated messages |

- Foot care |

|

Incentives |

- Smoking |

|

PA (MET) |

|

Dietary intake |

|

- Grains*

|

|

- Protein foods |

|

- Vegetables |

|

- Fruits |

|

- Dairy |

|

BG testing*

|

|

Zhang et al. (2024), China [A5] |

I: 947, |

BCW |

App |

Self-management education |

96 weeks (daily) |

Usual care |

HbA1c*

|

Self-care activity |

Quality of life |

|

C: 925 |

Goal setting |

BP |

|

Self-monitoring and recording |

BG*

|

|

Reminders |

BMI |

|

Incentives |

Lipid profiles |

|

Hypoglycemia |

|

Diabetic complications |

|

Firdaus et al. (2023), Malaysia [A6] |

I: 29, |

IFSMT |

App |

Face-to-face session: app usage and self-management |

5 weeks (daily) |

Usual care |

BG |

Dietary behavior*

|

|

|

C: 29 |

Self-management and foot care education |

Diabetic complications*

|

Foot care behavior*

|

|

Self-monitoring and recording |

|

Reminders |

|

Communication via chat |

|

Waller et al. (2023), Australia [A7] |

I: 176, |

COM-B |

SMS |

Self-management education |

24 weeks (1–12 weeks: daily, 13–24 weeks: 4 times/week) |

Usual care |

HbA1c |

|

Quality-adjusted life years |

|

C: 172 |

Unidirectional, semi-personalized text messages |

|

Jiang et al. (2022), Singapore [A8] |

I: 58, |

SCT |

App |

Self-management education |

24 weeks (daily) |

Usual care |

HbA1c*

|

Self-care activity |

Self-efficacy |

|

C: 56 |

Self-monitoring and recording |

- BG testing*

|

Quality of life |

|

Feedback |

- General diet |

|

- Specific diet |

|

- Physical exercise |

|

- Foot care |

|

- Smoking |

|

Sayin Kasar et al. (2022), Turkey [A9] |

I: 31, |

IMB |

SMS, phone call |

Face-to-face session: app usage and self-management |

12 weeks (SMS: daily, phone call: biweekly) |

Usual care |

HbA1c*

|

Self-care activity*

|

Self-efficacy*

|

|

C: 32 |

Self-management education |

BP (SBP*, DBP) |

Self-management perceptions*

|

|

Reminders |

BW*

|

|

Feedback via phone call |

|

Kim et al. (2019), South Korea [A10] |

I: 32, |

IMB |

App, phone call |

Face-to-face session: app usage and self-management |

8 weeks (app: daily, phone calls: weekly) |

Usual care |

HbA1c*

|

Self-care activity*

|

Self-efficacy |

|

C: 36 |

Goal setting |

BG*

|

Dietary intake |

Diabetes knowledge*

|

|

Self-monitoring and recording |

BMI |

- Total calorie intake*

|

Diabetes attitude |

|

Feedback via phone call |

- Carbohydrate intake*

|

Social support*

|

|

Communication via chat |

- Fat intake*

|

|

- Protein intake |

|

PA (steps/day) |

|

Benson et al. (2019), USA [A11] |

I: 60, |

HBM, TTM |

Phone call |

Goal setting |

48 weeks (once/month) |

Usual care |

HbA1c |

PA (min/day) |

|

|

C: 58 |

Self-management education |

BP |

Tobacco use |

|

Medication management |

BMI |

Dietary intake |

|

Motivational interviewing |

LDL-cholesterol |

- Breakfast |

|

Medication use |

- Fruits*

|

|

- Statin and aspirin |

- Vegetables |

|

- Whole grains |

|

Medication adherence |

|

- Diabetes*

|

|

- Cholesterol |

|

- Blood pressure |

|

Boel et al. (2019), Netherlands [A12] |

I: 115, |

FBM |

App |

Self-management education |

24 weeks (2–6 times/week) |

Usual care |

HbA1c |

Self-care activity |

Quality of life |

|

C: 115 |

Reminders |

BP |

Dietary intake |

Health status |

|

Unidirectional messages: specific goals, healthy lifestyle information and challenges, or questions |

BMI |

PA (MET) |

|

Lipid profile |

|

Hypoglycemia/glycemic variability |

|

Chao et al. (2019), Taiwan and China [A13] |

I: 62, |

TTM |

App |

Individualized self-management education |

72 weeks (daily) |

Usual care |

HbA1c*

|

Self-care activity |

Diabetes knowledge*

|

|

C: 59 |

Self-monitoring and recording |

BP |

- Dietary*

|

|

BMI |

- Exercise |

|

BW*

|

- Medicine taking |

|

- Monitoring |

|

- Health coping |

|

Ramadas et al. (2018), Malaysia [A14] |

I: 66, |

TTM |

Web portal |

Personalized dietary education |

48 weeks (biweekly) |

Usual care |

HbA1c |

Dietary behavior*: dietary stages of change |

Dietary knowledge*

|

|

C: 62 |

Reminders |

BG |

Dietary attitude*

|

|

Communication via chat |

|

Kleinman et al. (2017), India [A15] |

I: 44, |

HBM, TPB, self-efficacy |

App |

Self-monitoring and recording |

24 weeks (daily) |

Usual care |

HbA1c*

|

Self-care activity*

|

Self-efficacy |

|

C: 46 |

Reminders |

BP |

BG testing*

|

Distress |

|

Algorithmic message |

BG |

Medication adherence*

|

|

Communication via chat |

BMI |

|

Lipids profile |

|

WC |

|

Orsama et al. (2013), Finland [A16] |

I: 24, |

IMB |

App |

Self-monitoring and recording |

40 weeks (daily) |

Usual care |

HbA1c*

|

|

|

|

C: 24 |

Algorithm-based feedback |

BP |

|

BW*

|

|

Trief et al. (2013), USA [A17] |

I: 844, |

SCT |

Video call |

Goal setting |

240 weeks (once/4–6 weeks) |

Usual care |

HbA1c |

Self-care activity |

|

|

C: 821 |

Feedback via phone call |

Table 2.Behavior Change Techniques Taxonomy

|

BCT group |

BCT label |

A1 |

A2 |

A3 |

A4 |

A5 |

A6 |

A7 |

A8 |

A9 |

A10 |

A11 |

A12 |

A13 |

A14 |

A15 |

A16 |

A17 |

No. of studies |

|

1. Goals and planning |

1.1. Goal setting (behavior) |

√ |

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

10 |

|

1.2. Problem solving |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

|

√ |

5 |

|

1.4. Action planning |

|

|

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

|

√ |

8 |

|

1.5. Review behavior goals |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

2. Feedback and monitoring |

2.1. Monitoring of behavior by others without feedback |

|

√ |

|

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

3 |

|

2.2. Feedback on behavior |

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

11 |

|

2.3. Self-monitoring of behavior |

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

|

√ |

|

9 |

|

2.4. Self-monitoring of outcomes of behavior |

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

9 |

|

2.7. Feedback on outcomes of behavior |

|

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

√ |

√ |

5 |

|

3. Social support |

3.1. Social support (unspecified) |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

|

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

14 |

|

3.2. Social support (practical) |

|

√ |

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

4. Shaping of knowledge |

4.1. Instruction on how to perform the behavior |

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

|

√ |

14 |

|

5. Natural consequences |

5.1. Information about health consequences |

|

|

|

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

|

|

√ |

|

4 |

|

7. Associations |

7.1. Prompts/cues |

|

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

11 |

|

8. Repetition & substitution |

8.1. Behavioral practice/rehearsal |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

8.3. Habit formation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

8.7. Graded tasks |

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

√ |

3 |

|

9. Comparison of outcomes |

9.1. Credible source |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

|

4 |

|

10. Reward and threat |

10.2. Material reward (behavior) |

|

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

10.3. Non-specific reward |

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

10.4. Social reward |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

√ |

2 |

|

12. Antecedents |

12.2. Restructuring the social environment |

|

√ |

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

|

12.5. Adding objects to the environment |

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

|

|

|

√ |

|

√ |

|

√ |

√ |

|

9 |

|

13. Identity |

13.2. Framing/reframing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

15. Self-belief |

15.1. Verbal persuasion about capability |

√ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 |

|

No. of BCTs used in each study |

7 |

7 |

7 |

12 |

11 |

9 |

6 |

6 |

9 |

8 |

5 |

7 |

13 |

8 |

5 |

9 |

9 |

|

Table 3.

|

Items of theory coding scheme |

A1 |

A2 |

A3 |

A4 |

A5 |

A6 |

A7 |

A8 |

A9 |

A10 |

A11 |

A12 |

A13 |

A14 |

A15 |

A16 |

A17 |

n (%) |

|

1. Theory of behavior mentioned |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

17 (100.0) |

|

2. Targeted construct mentioned as predictor of behavior |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

14 (82.4) |

|

3. Intervention based on single theory |

+ |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

10 (58.8) |

|

4. Theory used to select recipients for the intervention |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

1 (5.9) |

|

5. Theory used to select intervention techniques |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

17 (100.0) |

|

6. Theory used to tailor intervention techniques to recipients |

+ |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

9 (52.9) |

|

7. All intervention techniques are explicitly linked to at least one theory-relevant construct |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

6 (35.3) |

|

8. At least one, but not all, of the intervention techniques are explicitly linked to at least one theory-relevant construct |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

7 (41.2) |

|

9. Group of techniques are linked to a group of constructs |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

9 (52.9) |

|

10. All theory-relevant constructs are explicitly linked to at least one intervention technique |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

– |

4 (23.5) |

|

11. At least one, but not all, of the theory-relevant constructs are explicitly linked to at least one intervention technique |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

10 (58.8) |

|

12. Theory-relevant constructs are measured |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

14 (82.4) |

|

13. Quality of measures |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

14 (82.4) |

|

14. Randomization of participants to condition |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

17 (100.0) |

|

15. Changes in measured theory-relevant constructs |

+ |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

– |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

10 (58.8) |

|

16. Mediational analysis of constructs |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

1 (5.9) |

|

17. Results discussed in relation to theory |

+ |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

9 (52.9) |

|

18. Appropriate support for theory |

+ |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

+ |

– |

+ |

+ |

+ |

– |

+ |

– |

6 (35.3) |

|

19. Results used to refine theory |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

– |

0 (0.0) |

|

No. of theory coding scheme used in each study |

14 |

8 |

9 |

12 |

5 |

9 |

5 |

8 |

10 |

14 |

9 |

13 |

13 |

15 |

10 |

9 |

12 |

|

REFERENCES

- 1. Jang W, Kim S, Son Y, Kim S, Kim HJ, Jo H, et al. Prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of type 2 diabetes in South Korea (1998 to 2022): nationwide cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2024;10:e59571. https://doi.org/10.2196/59571

- 2. NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in diabetes prevalence and treatment from 1990 to 2022: a pooled analysis of 1108 population-representative studies with 141 million participants. Lancet. 2024;404(10467):2077-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(24)02317-1

- 3. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas. 11th ed. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2025.

- 4. Statistics Korea. Causes of death statistics in 2023 [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2024 [cited 2025 July 16]. Available from: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301010000&bid=218&act=view&list_no=433106

- 5. International Diabetes Federation. Advocacy guide to the IDF Diabetes Atlas 2019 [Internet]. Brussels: International Diabetes Federation; 2019 [cited 2024 April 8]. Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org/resources/previous-editions/

- 6. Korean Diabetes Association. 2019 Treatment guideline for diabetes. 6th ed. [Internet]. Seoul: Korean Diabetes Association; 2019 [cited 2024 April 8]. Available from: https://www.diabetes.or.kr/bbs/?code=guide

- 7. Einarson TR, Acs A, Ludwig C, Panton UH. Prevalence of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes: a systematic literature review of scientific evidence from across the world in 2007-2017. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0728-6

- 8. Burch E, Ball L, Somerville M, Williams LT. Dietary intake by food group of individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;137:160-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2017.12.016

- 9. Fatehi F, Menon A, Bird D. Diabetes care in the digital era: a synoptic overview. Curr Diab Rep. 2018;18(7):38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-018-1013-5

- 10. He Q, Zhao X, Wang Y, Xie Q, Cheng L. Effectiveness of smartphone application-based self-management interventions in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Adv Nurs. 2022;78(2):348-62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14993

- 11. Kerr D, Ahn D, Waki K, Wang J, Breznen B, Klonoff DC. Digital interventions for self-management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2024;26:e55757. https://doi.org/10.2196/55757

- 12. Cho YM, Lee S, Islam SMS, Kim SY. Theories applied to m-Health interventions for behavior change in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24(10):727-41. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2017.0249

- 13. McSharry J, Byrne M, Casey B, Dinneen SF, Fredrix M, Hynes L, et al. Behaviour change in diabetes: behavioural science advancements to support the use of theory. Diabet Med. 2020;37(3):455-63. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14198

- 14. Patton DE, Hughes CM, Cadogan CA, Ryan CA. Theory-based interventions to improve medication adherence in older adults prescribed polypharmacy: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2017;34(2):97-113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-016-0426-6

- 15. Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81-95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6

- 16. Michie S, Prestwich A. Are interventions theory-based?: development of a theory coding scheme. Health Psychol. 2010;29(1):1-8. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016939

- 17. Seo HJ. The scoping review approach to synthesize nursing research evidence. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2020;32(5):433-9. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2020.32.5.433

- 18. Peters MD, Marnie C, Colquhoun H, Garritty CM, Hempel S, Horsley T, et al. Scoping reviews: reinforcing and advancing the methodology and application. Syst Rev. 2021;10(1):263. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01821-3

- 19. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- 20. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467-73. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0850

- 21. Alsayed AO, Ismail NA, Hasan L, Embarak F. A comprehensive review of modern methods to improve diabetes self-care management systems. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2023;14(9):182-203. http://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2023.0140920

- 22. Choi J, Park YC, Choi S. Development of a mobile-based self-management health alarm program for obese children in South Korea and a test of its feasibility for metabolic outcomes: a study based on the information-motivation-behavioral skills model. Child Health Nurs Res. 2021;27(1):13-23. https://doi.org/10.4094/chnr.2021.27.1.13

- 23. Mohamed A, Staite E, Ismail K, Winkley K. A systematic review of diabetes self-management education interventions for people with type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Asian Western Pacific (AWP) region. Nurs Open. 2019;6(4):1424-37. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.340

- 24. Mehraeen E, Mehrtak M, Janfaza N, Karimi A, Heydari M, Mirzapour P, et al. Design and development of a mobile-based self-care application for patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2022;16(4):1008-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/19322968211007124

- 25. Wu Y, Yao X, Vespasiani G, Nicolucci A, Dong Y, Kwong J, et al. Mobile app-based interventions to support diabetes self-management: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials to identify functions associated with glycemic efficacy. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2017;5(3):e35. https://doi.org/10.2196/mhealth.6522

- 26. Cho ME, Hwang SK. Self-efficacy-based interventions for patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a systematic review. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2024;18(4):420-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2024.09.002

- 27. Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Bryan AD, Misovich SJ. Information-motivation-behavioral skills model-based HIV risk behavior change intervention for inner-city high school youth. Health Psychol. 2002;21(2):177-86.

- 28. Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. 4th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. p. 23-8.

- 29. Cradock KA, OLaighin G, Finucane FM, Gainforth HL, Quinlan LR, Ginis KA. Behaviour change techniques targeting both diet and physical activity in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2017;14(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0436-0

- 30. Doshmangir P, Jahangiry L, Farhangi MA, Doshmangir L, Faraji L. The effectiveness of theory- and model-based lifestyle interventions on HbA1c among patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health. 2018;155:133-41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.11.022

- 31. Timlin D, McCormack JM, Kerr M, Keaver L, Simpson EE. Are dietary interventions with a behaviour change theoretical framework effective in changing dietary patterns? A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1857. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09985-8