Abstract

-

Purpose

This scoping review aimed to comprehensively examine environmental and individual factors contributing to clinical practice stress among nursing students in South Korea and to provide evidence-based recommendations for improving the clinical education environment.

-

Methods

A scoping review was conducted following Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage framework and the PRISMA-ScR guidelines. Relevant studies published between January 2016 and March 2025 were identified through searches of domestic databases (KCI, RISS) and international databases (PubMed, CINAHL) using predefined keywords. A total of 18 studies met the inclusion criteria. Data were extracted using a standardized template and categorized by study characteristics, methodological features, and stress-related variables.

-

Results

Most included studies were conducted after 2022 and involved students from multiple institutions. Environmental stressors identified included poor clinical setting quality, lack of instructor support, interpersonal challenges, limited educational infrastructure, and disruptions caused by new infectious diseases. At the individual-level, resilience, coping strategies, and emotional regulation were the most frequently studied variables. Among these, resilience was consistently reported as a protective factor against stress, while incivility emerged as the most prominent environmental stressor. Multiple regression models indicated that stress-related factors explained between 18.0% and 75.6% of the variance in outcomes.

-

Conclusion

Clinical practice stress in nursing students results from a dynamic interaction between environmental and individual factors. Nursing education programs should incorporate resilience-enhancing interventions, strengthen collaboration with clinical sites, and adopt flexible educational methods, such as simulation-based training, particularly during periods of restricted clinical access.

-

Key Words: Environmental exposure; Nursing students; Psychological stress; Scoping review

INTRODUCTION

With the continuing advancement of medical technology and heightened public awareness of healthcare standards, the demand for improved healthcare services has risen markedly. These developments are closely tied to nursing education [

1]. The World Health Organization has emphasized the importance of investing in nursing education and supporting the development of qualified nurses worldwide, particularly by reinforcing educational programs that build advanced nursing competencies [

2]. Reflecting this trend, the Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing Education (KABONE) revised its standards in the fourth accreditation cycle, shifting the minimum requirement for clinical practice from 1,000 hours per student to a minimum of 22 clinical credits [

3].

The clinical practicum is a core element of nursing education that enables students to apply theoretical knowledge in real clinical contexts and to internalize essential competencies. Despite its importance, clinical training in Korea is often limited to observational experiences, partly due to heightened awareness of patient rights and a shortage of qualified clinical educators [

4]. As of 2021, the number of university nursing departments in Korea had increased by approximately 66% compared to 2009 [

5]. With the rising number of nursing students, securing high-quality clinical practice sites has become a major challenge for nursing universities. Moreover, expanding student enrollment has intensified competition for clinical placements, and the varied characteristics of clinical institutions demand that students quickly adapt each time their placement changes [

6].

External influences including new and emerging infectious diseases, changes in healthcare workforce policy, and institutional variation in practicum systems have further disrupted the clinical training environment [

7]. These disruptions highlight the urgent need to understand how diverse and evolving conditions contribute to nursing students’ clinical practice stress.

Clinical practice stress refers to a state of tension that hinders students’ performance, caused by anxiety, fear, worry, or physical discomfort resulting from practicum-related experiences [

8]. Stressors are multifaceted, including discrepancies between theory and practice, non-educational environments, lack of interpersonal experience, repetitive basic tasks, insufficient professional knowledge, and low confidence [

9]. Previous studies have largely emphasized psychological or personality traits as individual predictors of stress. However, several studies have also reported that clinical learning conditions and environmental characteristics exert substantial influence on practicum-related stress [

10,

11].

In this study, factors contributing to clinical practice stress are broadly categorized into two domains: individual and environmental. Individual factors encompass personal attributes such as self-efficacy, personality traits, coping ability, academic preparedness, and psychological resilience. Environmental factors include external elements such as the learning atmosphere of the clinical site, quality of interactions with staff, workload, patient acuity, and institutional support systems. This classification is based on the Stress Interaction Model, which conceptualizes stress as the outcome of interactions between an individual and their environment [

12]. By applying this theoretical perspective, the study seeks to systematically explore how the dynamic interplay between personal characteristics and contextual conditions contributes to clinical practice stress.

The clinical practicum environment particularly the atmosphere of the clinical site and interpersonal relationships directly affects nursing students’ perceptions, emotional well-being, and learning performance. A supportive environment, characterized by constructive guidance from preceptors and a positive unit culture, enhances students’ sense of belonging while reducing anxiety [

5]. Nevertheless, previous studies have primarily focused on psychological and academic factors, often overlooking environmental influences. For example, a domestic review covering 2015 to 2020 did not include stressors related to major public health events, and a meta-analysis categorized stress-related factors without adequately addressing environmental components [

11,

13]. Given these gaps, it is necessary to investigate environmental and systemic contributors such as institutional readiness, infection-related disruptions, and clinical education infrastructure that shape clinical practice stress.

This study therefore aims to synthesize existing evidence through a scoping review, examine current conditions in clinical practicum settings, and identify opportunities for educational improvement. The findings are intended to support collaborative strategies to enhance clinical training environments, strengthen instructor competencies, and refine instructional approaches in nursing education.

Accordingly, this review seeks to address a critical gap by systematically mapping and classifying stress-related variables, analyzing the representation of both internal and external influences in the literature, and identifying research patterns and deficiencies. To ensure comprehensiveness, the literature search period was set from 2016 to 2025, capturing the most recent decade of scholarship. This timeframe was selected to reflect evolving developments in nursing education, clinical training environments, and policy contexts, including significant changes before and after major infectious disease outbreaks. By encompassing this period, the review provides timely insights into individual and environmental factors affecting nursing students’ clinical practice stress and offers evidence to inform current educational strategies and institutional policies. Through a scoping review of domestic literature published between 2016 and 2025, this study aims to identify and classify stress-related variables, analyze current research trends and methodologies, and provide insights that can inform the development of more effective clinical education strategies. Ultimately, the findings are expected to support improvements in clinical learning environments, guide institutional decision-making, and contribute to the design of evidence-based interventions that reduce stress and improve nursing students’ practicum experiences.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This study employed a scoping review methodology to explore and synthesize research on environmental and individual factors associated with clinical practice stress among nursing students in South Korea. Unlike traditional systematic reviews, scoping reviews are particularly suited for mapping broad or complex areas of inquiry involving heterogeneous study designs and diverse interventions. Following the foundational framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [

14], this review aimed to examine the extent, range, and nature of the existing literature, identify key concepts, and summarize findings relevant to clinical practice stress. To ensure methodological rigor and transparency, the review process was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [

15].

Based on the PCC framework (Population–Concept–Context) outlined by Levac et al. [

16], this study formulated its research questions as follows: the population (P) consists of nursing students, the concept (C) relates to clinical practicum education, and the context (C) is situated within nursing colleges and hospital-based clinical settings. Accordingly, the research questions were: “What are the trends in research on environmental and individual factors related to clinical practice stress among nursing students?”, “What specific environmental and personal conditions contribute to this stress?”, and “What areas of the clinical practice environment require improvement, and what support is needed to better assist students in the future?”

To comprehensively review literature related to clinical practice among Korean nursing students, this study used two representative domestic databases the Korean Citation Index (KCI) and the Research Information Sharing Service (RISS). These databases ensured the inclusion of Korean-language publications and allowed for the integration of journal articles, academic dissertations, and gray literature. In addition, two international databases were used PubMed and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) to identify English-language studies examining clinical practice stress among nursing students.

Literature searches were conducted across both domestic and international databases. Korean sources (KCI and RISS) were searched using terms such as “nursing student,” “clinical practice,” “stress,” and “influencing factor.” For international databases, PubMed and CINAHL were queried using combinations of “nursing students,” “clinical practice,” “stress,” “related factor,” and “Korean.” The KCI search strategy was: (KEYALL “nursing students”) AND (KEYALL “clinical practice”) AND ((KEYALL “stress”) OR (KEYALL “influencing factor”)) AND Publish (2016Jan:2025Mar). The RISS search strategy was: (ALL: nursing students) AND (ALL: clinical practice AND ((ALL: stress) OR (ALL: influencing factor))) AND Publish (2016~2025).

3. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

To ensure relevance and quality, explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria were established prior to screening. The inclusion criteria were: (1) peer-reviewed journal articles published between January 2016 and March 2025; (2) studies focusing on clinical practice stress among nursing students in South Korea; (3) research examining either environmental or individual factors related to clinical practicum stress; and (4) publications written in Korean or English. These criteria were intended to capture recent and contextually relevant studies reflecting changes in clinical education environments, including those influenced by emerging infectious diseases, healthcare system instability, and institutional policy reforms.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) studies not involving nursing students as the target population; (2) research not focused on clinical practice or stress in clinical practice; (3) non-empirical works such as opinion pieces, editorials, or narrative reviews; (4) conference abstracts, posters, or book chapters; and (5) duplicate publications across databases. The screening and eligibility process was guided by these criteria to ensure that only studies with direct relevance to the research questions and conceptual framework were included in the final analysis.

4. Screening Procedure

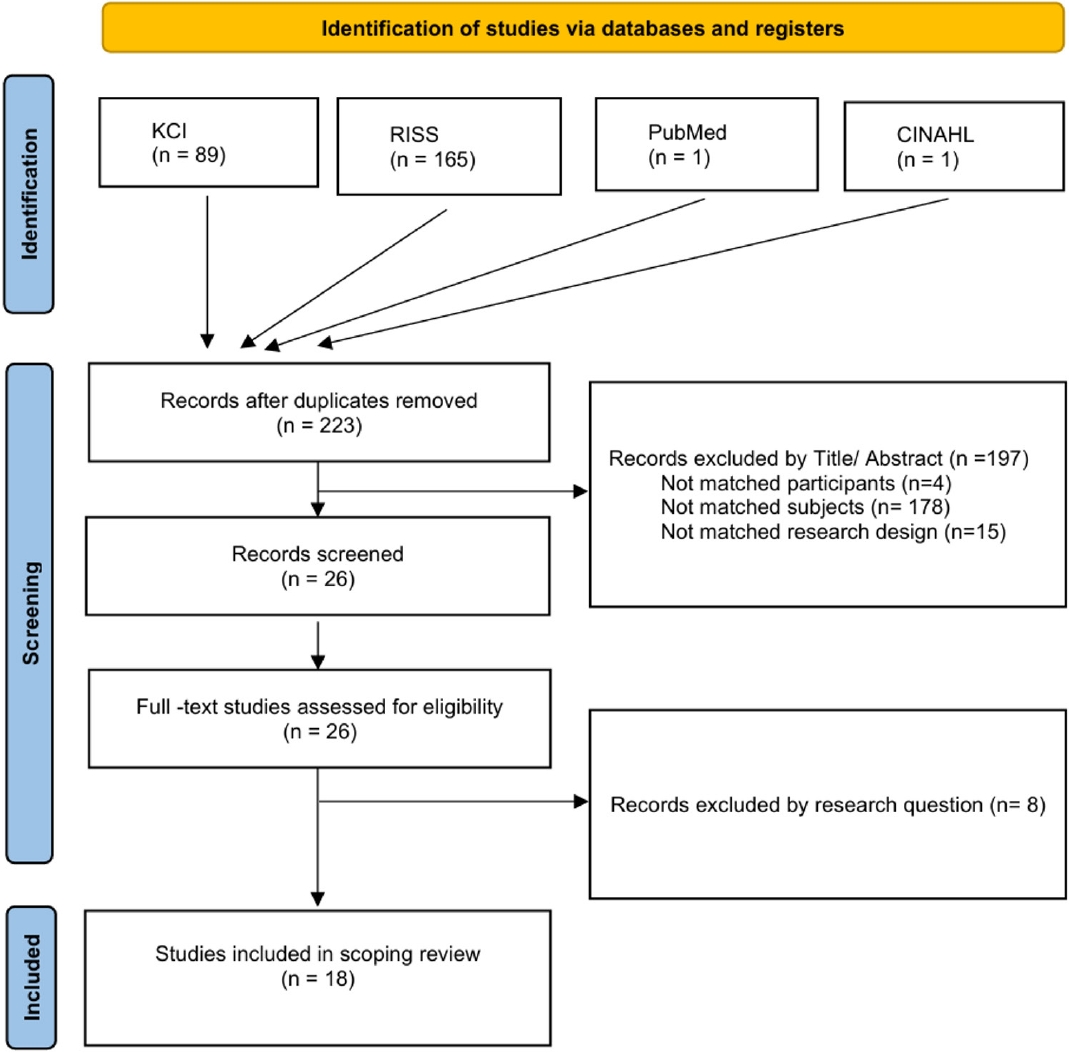

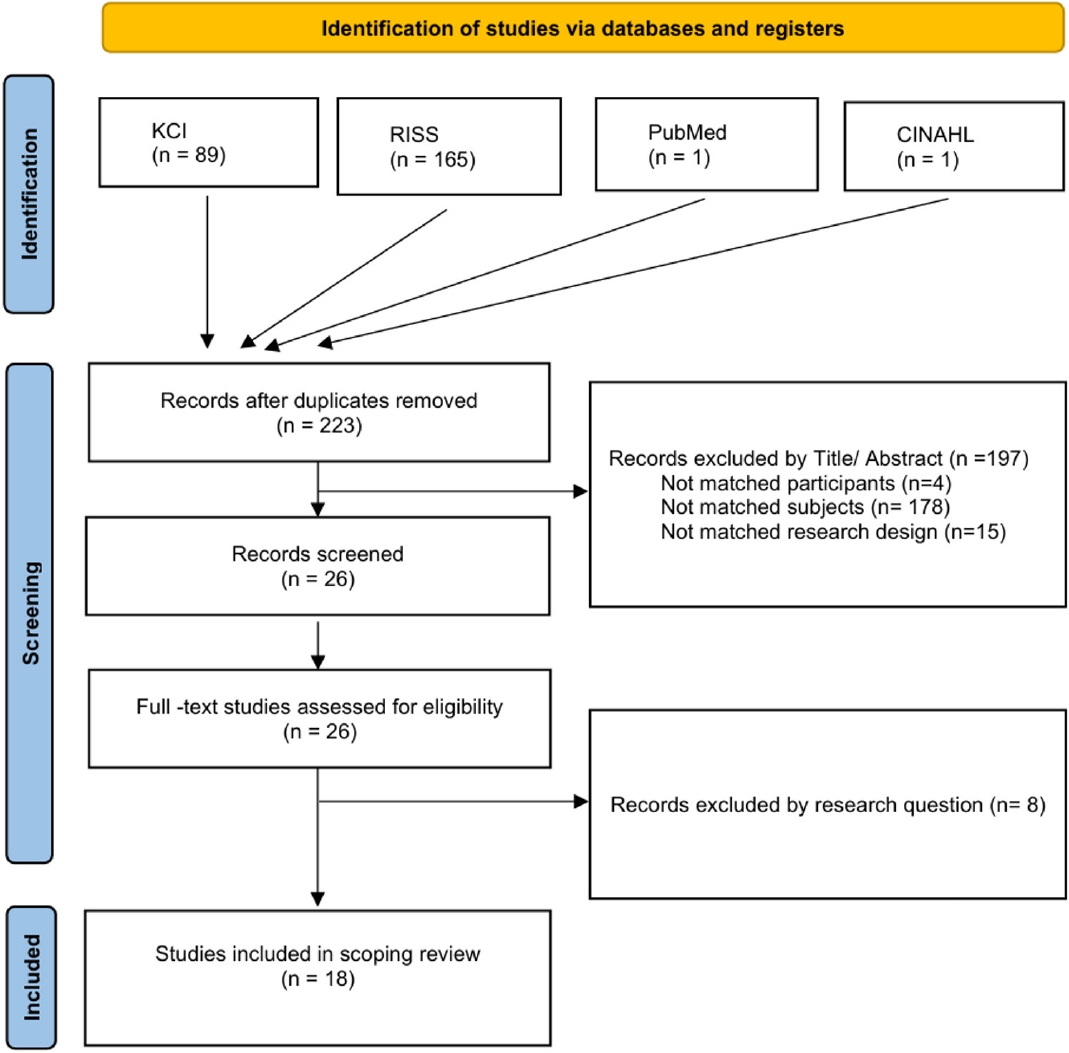

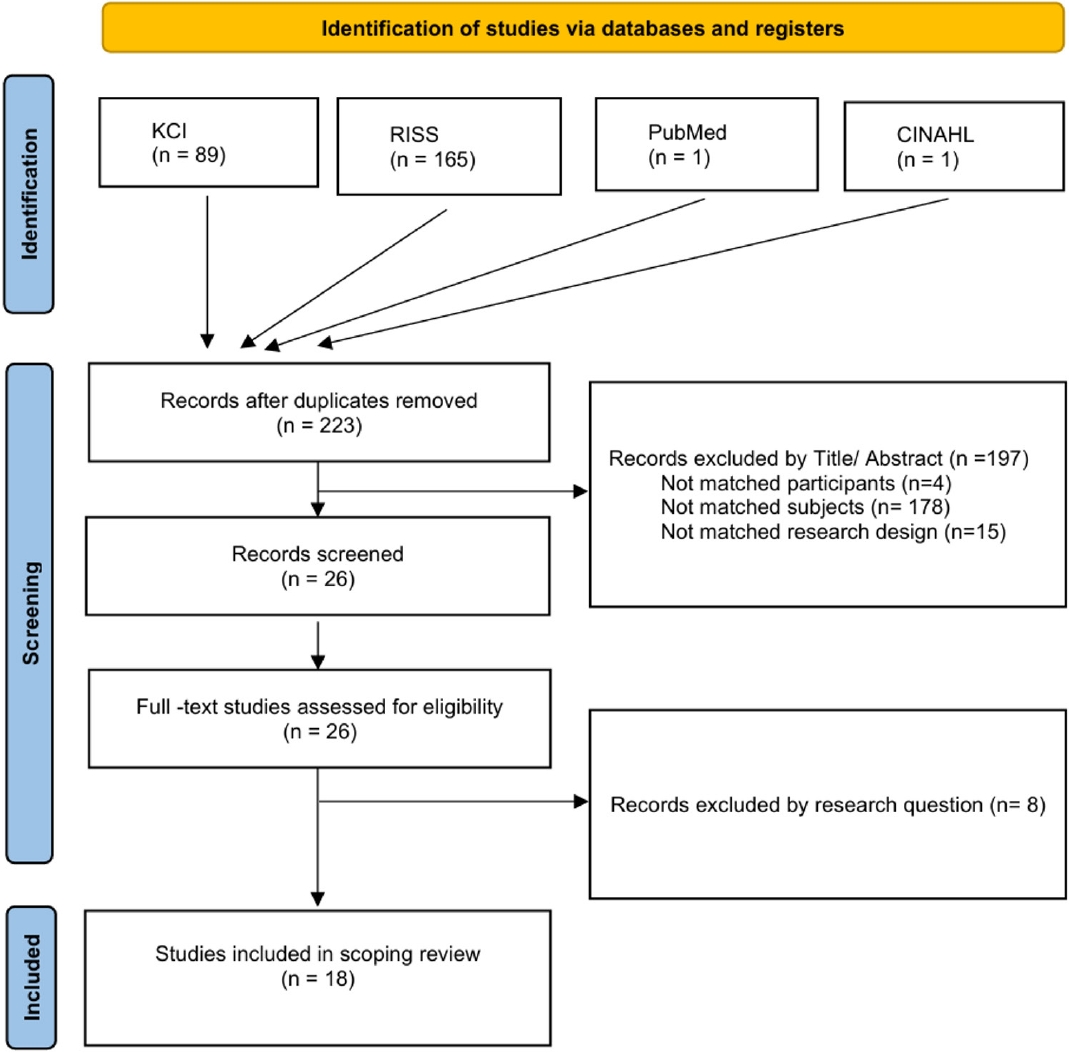

The initial database search identified 223 articles. After duplicate removal and title/abstract screening, 26 articles were retained for full-text review. Final inclusion was determined through independent assessments by two reviewers a primary researcher and a doctoral-level research assistant—followed by consensus discussions. Disagreements were resolved through meetings and mutual agreement. Ultimately, 18 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the final analysis (

Figure 1).

The quality of the selected studies was assessed using the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist [

15]. This tool evaluates six domains: title/abstract, introduction, methods, results, discussion, and other reporting elements. Data were systematically extracted using a standardized template developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). One researcher independently extracted the data, while a research assistant cross-checked all entries to ensure accuracy and consistency. Extracted fields included authors, year of publication, sample characteristics, research design, and variables examined, with particular attention to identifying and classifying factors associated with clinical practice stress.

Data analysis proceeded in three phases. First, descriptive characteristics such as publication year, study design, sample size, and institutional setting were summarized. Second, variables associated with clinical practice stress were identified and analyzed in terms of frequency and significance. Third, each variable was categorized as either an individual-level or environmental-level factor, enabling a structured synthesis of findings across the included studies.

To ensure validity, one researcher and a research assistant independently classified the variables according to predefined criteria. They then engaged in iterative discussions to resolve discrepancies, refining the categorization process until full consensus was reached. This collaborative approach strengthened the consistency and reliability of the classification framework. The final synthesis provided a comprehensive and contextually grounded understanding of the multidimensional factors influencing clinical practice stress in nursing students and highlighted potential areas for educational intervention.

RESULTS

1. General Characteristics of Included Studies

A total of 18 studies were included in the final analysis. The distribution of publication years was as follows: two studies were published between 2016 and 2017, one between 2018 and 2019, three between 2020 and 2021, five between 2022 and 2023, and seven between 2024 and 2025. Notably, more than half (66.7%) of the studies were published after 2021, reflecting a growing research interest in the topic in recent years (

Table 1).

Regarding participants, two studies focused exclusively on third-year nursing students, four on fourth-year students, and ten included both third- and fourth-year students. One study encompassed students from all academic years, while another included both current students and recent graduates, without specifying academic level. Most studies (n=16) employed a descriptive survey design, while one quasi-experimental study and one qualitative study were identified. Sample sizes varied considerably. One study included fewer than 50 participants, three studies had between 51 and 100, five had between 101 and 150, three had between 151 and 200, and six studies involved more than 200 participants. Comparisons between single-institution and multi-institution studies revealed important contextual differences: single-institution studies often highlighted localized factors, such as department-specific policies or unique practicum arrangements, whereas multi-institution studies captured a broader spectrum of stressors arising from institutional diversity, regional healthcare resources, and inter-university differences in practicum conditions. This comparison underscores the importance of institutional context in shaping nursing students’ stress experiences. Additionally, 11 studies (61.1%) explicitly described clinical practice environment characteristics such as hospital affiliation, practicum type, or setting.

2. Variables Associated with Clinical Practice Stress

Across the 18 included studies, a variety of factors were reported to influence clinical practice stress among nursing students. The most frequently investigated variable was resilience, examined in four studies. Social support and incivility were each assessed in three studies, while violence exposure, non-face-to-face clinical education, major satisfaction, and coping strategies were addressed in two studies each. Additional variables examined in individual studies included anxiety, sleep quality, teaching effectiveness, peer caring behaviors, maladaptive perfectionism, self-leadership, academic burnout, depression, pandemic-related stress, adaptation to academic departments, and confidence in core nursing skills (

Table 2).

In terms of grade level, most studies (n=14) targeted junior and senior students (3rd–4th years), who are typically exposed to more intensive clinical training. Only one study included first- and second-year students, while another included a wider range of participants, including graduate students. With respect to practicum experience, 17 of the 18 studies included participants with actual clinical experience, whereas only one focused on students without clinical exposure, investigating simulated or pre-clinical interventions instead.

Descriptions of the clinical practice environment varied. Seven studies did not explicitly specify environmental contexts, while others detailed aspects such as the number of practicum institutions, affiliated hospitals, clinical departments, or duration of clinical practice. Comparative analysis showed that multi-institutional studies tended to report greater variability in stressors due to differences in institutional culture, while single-institution studies concentrated more on localized issues, including hospital policies or departmental dynamics. Other noted contextual factors included hospital size, departmental specialization, and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)–related modifications to training. These environmental conditions functioned not only as study variables but also as important contextual factors mediating the relationship between individual characteristics and clinical stress.

Variables positively associated with clinical practice stress (i.e., risk factors) included incivility, emotion-focused coping, heightened emotional responses, transition shock, anxiety, maladaptive perfectionism, exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals, academic burnout, depression, and pandemic-related stress. Among these, incivility was the most consistently reported stress-inducing factor. In contrast, negatively associated variables (i.e., protective factors) included resilience, sleep quality, social support, teaching effectiveness, peer caring behavior, major satisfaction, and departmental adaptation. Resilience was the most frequently examined protective factor, identified in four studies.

Multiple regression analysis was employed in nine studies to evaluate the explanatory power of these variables. The models’ explanatory power ranged from 18.0% to 75.6%, indicating substantial variability. Higher explanatory power was generally observed in multi-institution studies that incorporated both individual and environmental factors, whereas single-institution studies tended to demonstrate narrower explanatory ranges, reflecting more limited contextual variation.

3. Categorization of Environmental and Individual Factors

Across the 18 reviewed studies, a total of 41 variables were identified as influencing clinical practice stress among nursing students, comprising 22 environmental and 19 individual-level factors (

Table 3). For most variables, the direction of association (positive or negative) was statistically confirmed; however, several inconsistencies were noted, as described below (

Supplementary Data 1).

Among environmental factors, the most frequently reported was incivility, cited in four studies [A13,A15,A16,A17], all of which statistically confirmed its positive association with stress. Other commonly reported environmental stressors included violence [A11,A17], transition shock [A2], and difficulties related to clinical placements in non-affiliated hospitals or housing [A8]. Each of these demonstrated a statistically confirmed positive association with stress in multiple studies. New infectious diseases were identified as significant stressors in two studies [A1,A12], underscoring the contemporary relevance of infection-related challenges in clinical education. Additional environmental factors, such as teaching effectiveness, academic burnout, online clinical practice, and exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals, were mentioned less frequently but, when analyzed, generally showed a positive association with stress.

Regarding individual-level factors, resilience emerged as the most consistently identified protective factor, reported in five studies [A1,A2,A4,A15,A17], all of which statistically confirmed its negative association with stress, reinforcing its buffering effect. Coping strategies were examined in four studies [A1,A3,A11,A17]; while most confirmed a negative association with stress, suggesting an effective role in stress management, one study [A11] found that maladaptive coping styles could instead show a positive association, illustrating that the impact of coping depends on the specific strategy employed. Other individual-level factors included emotional responses [A17], self-leadership [A3], major satisfaction [A3], and psychological symptoms such as anxiety [A12] and depression [A5]. These generally aligned with theoretical expectations—for example, anxiety and depression were positively associated with stress. Less frequently mentioned variables, such as communication ability [A10] and health status [A12], were also statistically linked to stress outcomes.

Overall, the findings indicate that while environmental stressors particularly incivility and institutional characteristics are commonly documented and tend to exacerbate stress, individual traits such as resilience and adaptive coping play a critical mitigating role. Furthermore, comparisons across different periods and settings suggest that both global crises (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) and local institutional cultures must be considered when designing stress management interventions for nursing students. The statistical confirmation of these associations across multiple studies strengthens the empirical foundation of this review, although minor inconsistencies (such as the differential effects of coping strategies) highlight the complexity of stress-related interactions. These insights underscore the importance of multifaceted approaches that simultaneously foster individual resilience and improve the quality of the clinical learning environment.

DISCUSSION

This scoping review analyzed 18 studies conducted in South Korea over the past decade that examined clinical practice stress among nursing students. Using the scoping review methodology, the studies were reviewed in terms of general characteristics, clinical training environments, key variables, and the relationships among those variables. Furthermore, factors were categorized into environmental and individual domains to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the issue. Based on these findings, this review sought to identify key environmental contributors to clinical practice stress and propose strategies to improve the clinical training environment for nursing students.

The review showed that more than half of the selected studies (n=12, 66.7%) were published after 2022, indicating growing scholarly attention to this topic in recent years. Nine studies were conducted within a single university, while the other nine involved multiple institutions, including some using online formats. Importantly, seven studies did not explicitly describe the characteristics of the clinical training environment. This is consistent with earlier reviews, where data were often collected across multiple institutions but without clear differentiation or analysis of environmental characteristics [

13]. To address this gap, the present review systematically identified whether environmental characteristics were reported and provided in-depth analysis of their influence.

Key variables associated with clinical practice stress included resilience, social support, incivility, exposure to violence, non-face-to-face clinical education, major satisfaction, and coping strategies. Factors positively associated with stress included violence, emotion-focused coping, emotional responses, incivility, transition shock, anxiety, maladaptive perfectionism, exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals, academic burnout, depression, pandemic-related stress, and ineffective coping styles. Conversely, negatively associated factors included clinical learning environment quality, sleep quality, resilience, teaching effectiveness, peer caring behaviors, self-leadership, social support, departmental adaptation, and major satisfaction.

When compared with earlier reviews, notable differences emerged. Previous studies often identified major satisfaction as the most frequent protective factor [

17], while stressors included empathy-related burden, burnout, and coping styles [

11]. In contrast, the present review found resilience to be the most frequently reported protective factor. This shift may reflect the growing recognition of students’ internal coping mechanisms and psychological resources as critical determinants of stress outcomes. The increased reporting of incivility and violence as stressors may also be linked to recent advances in student rights education and safety training initiatives promoted by the KABONE. Unlike prior reviews, which tended to classify factors as either “protective” or “risk” variables [

11,

13], the present review distinguished them as positively or negatively associated factors. This approach reduces interpretive ambiguity and allows for clearer analysis. Additionally, this review examined the explanatory power of multiple regression models to evaluate how well these variables predicted clinical practice stress, thereby highlighting which combinations had the strongest influence.

Environmental factors identified in this study were further categorized into seven domains: clinical practice environment, educational environment, system/policy-related factors, interpersonal relationships, social support, instructional quality, and infection-related factors. These findings are consistent with prior research indicating that clinical environmental conditions such as incivility, stress, and violence—are strongly linked to stress in nursing students [

11]. While earlier studies acknowledged these stressors, their relative importance was often underemphasized. In contrast, this review placed greater emphasis on environmental components, aligning with evidence that students’ stress levels are shaped by both the quality of training conditions and the degree of institutional preparedness [

10].

Prior literature has emphasized the need for structural reforms in clinical education. For example, Yang et al. [

18] proposed the implementation of dedicated clinical nurse educators to improve educational quality and enhance instructor effectiveness. Similarly, other studies have reported that inadequate practicum conditions and unfamiliar clinical environments can heighten nursing students’ anxiety and stress [

19]. Internationally, innovative training models such as capstone practicums and 1:1 shadowing with experienced nurses during 12-hour shifts have been implemented in the United States to promote experiential learning without traditional classroom instruction. These models suggest that collaboration with clinically competent and pedagogically trained instructors, along with alignment to learning rubrics and expected outcomes, is equally essential in the Korean context.

Environmental stressors associated with emerging infectious diseases were frequently highlighted in this review [A1,A7,A10,A12]. The recent surge in novel infectious threats has intensified both theoretical and clinical learning burdens, disrupting traditional practicum schedules and driving shifts toward online and simulation-based alternatives. For instance, pandemic-related disruptions exemplify how external public health crises can severely limit access to clinical sites while creating substantial emotional strain for students. Majrashi et al. [

20] similarly observed that the disproportionate weighting of clinical practice credits in nursing curricula significantly contributes to stress. Cho [

21] further argued that external factors—including new infectious threats, healthcare workforce instability, and policy changes—must be considered to ensure a safe and stable educational environment during periods of systemic disruption. Issues such as infection risk, reduced practicum availability, and excessive reliance on virtual clinical training were identified as critical challenges. These findings underscore the urgent need for flexible, infection-resilient educational models, such as simulation-based learning and scenario-driven online modules, which reflect real clinical contexts and can serve as both substitutes and complements to field training.

In March 2025, the Korean Ministry of Health and Welfare launched an initiative to support the establishment and expansion of nursing simulation centers. This initiative aims to foster simulation-based education by creating a National Nursing Simulation Consortium system [

22]. Such a system has the potential to establish nationwide infrastructure for simulation-based clinical training and to build a systematic network of skilled educators. Furthermore, this project is expected to play a pivotal role in long-term educational policy and workforce development strategies, positioning simulation education not as a supplementary method but as a central clinical education strategy in response to unpredictable external factors, including emerging infectious diseases.

With regard to individual-level factors, resilience and coping strategies consistently emerged as critical variables influencing clinical practice stress [A1,A2,A15]. These findings align with prior research that has identified emotional intelligence, professional identity, and clinical competence as key attributes in stress regulation [

11]. Resilience, in particular, functions as a psychological buffer that mitigates stress [

23]. Therefore, educational interventions should be designed to enhance resilience and provide emotional support, including through online programs that prepare students to navigate challenging clinical environments. Some universities have already adopted non-face-to-face coaching and extracurricular support programs [

24], and nursing schools are encouraged to expand such approaches. Faculty and curriculum developers should also consider embedding structured resilience training, stress management workshops, and scenario-based simulations into the core curriculum. In addition, institutional policies must address environmental stressors directly by implementing anti-incivility protocols, providing access to counseling services, and ensuring safe housing and placement arrangements for off-campus practicums. These combined strategies can address the key stress-related variables identified in this review and facilitate the translation of research findings into actionable educational and administrative reforms.

Importantly, while the RESULTS section reported that the explanatory power of multiple regression models ranged from 5.2% to 75.6%, this discussion highlights a consistent trend: models combining both individual factors (such as resilience, coping strategies, and self-leadership) and environmental factors (such as incivility, violence exposure, and inadequate practicum conditions) demonstrated higher explanatory power, often exceeding 50% [

5,

11,

17]. In contrast, studies that examined only individual or only environmental variables yielded narrower explanatory ranges [

3,

8]. This pattern suggests that clinical practice stress is best explained through an integrated model that incorporates both personal psychological resources and contextual stressors [

2]. Notably, resilience and coping strategies emerged as the most robust negative predictors across high-explanatory models [

1,

4,

15], whereas incivility and transition shock were the most consistently identified positive predictors [

11,

16]. By articulating these statistical patterns, this review strengthens the empirical basis for designing multidimensional interventions that simultaneously address individual resilience and environmental improvements in clinical training.

During the categorization process, certain variables such as “burnout” and “transition shock” posed challenges due to conceptual overlap across domains. For instance, burnout was described in both individual and environmental contexts, reflecting its multidimensional nature, which encompasses personal psychological responses as well as systemic educational pressures. Similarly, transition shock, though largely associated with systemic placement issues, also intersects with individual-level adaptation. This ambiguity was addressed through iterative discussion and consensus-building among reviewers during the data analysis phase. By acknowledging and reflecting on these overlaps, this review enhances the conceptual rigor of its categorization process and encourages future research to develop clearer definitions and operational boundaries for commonly overlapping constructs.

In summary, the findings of this review reaffirm the importance of both environmental and individual factors in contributing to clinical practice stress among nursing students. Moving forward, research in this area is expected to expand, requiring multifaceted approaches that incorporate both internal psychological resources and external systemic influences. Future work should also investigate how these insights can be systematically integrated into nursing accreditation standards and faculty development programs to ensure sustained institutional commitment to student well-being. Given the persistent constraints in practicum environments, future studies should explore strategies to strengthen academic–clinical partnerships through structured practicum agreements, appointment of clinical instructors and preceptors, and the integration of safety and human rights training. Furthermore, logistical challenges—such as housing arrangements for off-campus practicum placements—merit further examination to ensure equitable access to high-quality clinical education.

Specifically, resilience, which consistently emerged as a factor negatively associated with clinical practice stress, could be intentionally fostered within nursing curricula by incorporating modules on stress management techniques, peer support activities, and opportunities for reflective practice. These interventions would help students strengthen psychological endurance. Coping strategies, another factor negatively associated with stress, can be further supported through scenario-based simulations and guided debriefings that enable students to explore and apply adaptive coping methods in realistic clinical situations. Conversely, to address stress-inducing factors such as incivility and exposure to violence, institutions should establish clear reporting channels, provide workshops to cultivate a respectful workplace culture, and implement systematic monitoring within practicum sites. Institutional policies could also mandate minimum standards for practicum quality, such as maintaining appropriate student-to-preceptor ratios and ensuring supportive learning environments. By aligning these curriculum enhancements and policy initiatives with the variables identified in this review, nursing programs will be better positioned to support students in managing stress and preparing for the complexities of clinical practice.

Despite the comprehensive scope of this review, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, all included studies were conducted in South Korea, which may restrict the generalizability of findings to broader international contexts. Cultural, institutional, and educational differences across countries may produce stressors or coping mechanisms not captured in this analysis. Second, although only peer-reviewed articles were included, methodological variability across studies may still have influenced the consistency of findings, despite quality appraisal using the STROBE checklist. Third, heterogeneity in study designs, measurement tools, and variable definitions posed challenges in synthesizing and comparing results, particularly when evaluating the strength of associations. Conceptual overlaps in variable categorization—such as with “burnout” and “transition shock” also highlight the need for clearer operational definitions in future research.

Considering these limitations, future studies would benefit from cross-cultural comparative analyses to examine how clinical practice stress is experienced across diverse healthcare education systems. Moreover, the development of standardized, validated instruments to measure environmental and individual stress-related variables is essential for improving consistency across studies. Longitudinal research tracking stress trajectories throughout students’ academic years would also provide a more dynamic understanding of stress development and resilience-building processes.

CONCLUSION

This scoping review synthesized evidence from 18 domestic studies conducted over the past decade to identify and categorize factors associated with clinical practice stress among nursing students. The findings demonstrate that stress is shaped not only by individual characteristics such as resilience and coping strategies but also by environmental influences, including the quality of the clinical training environment, interpersonal dynamics, perceived social support, and institutional educational conditions.

Importantly, the evolving healthcare landscape—marked by the transition to remote practicums during recent infectious disease outbreaks and compounded by systemic disruptions such as the 2024 physician strike has further complicated the clinical learning experience for nursing students. These contextual shifts underscore the need for nursing education institutions to systematically assess and adapt to barriers in the clinical training environment to reduce stress and safeguard the overall quality of nursing education.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declared no conflict of interest.

-

FUNDING

None.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Park Soo hyung, Senior Clinical Research Associate at Premier Research, for dedicated assistance with data collection and coordination throughout the study.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

No new data were created or analyzed during this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Figure 1.Flow Diagram of the Literature Selection Process. CINAHL=Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; KCI=Korean Citation Index; RISS=Research Information Sharing Service.

Table 1.General Characteristics of Included Studies, Participants, and Clinical Practice Environment (N=18)

|

Variables |

Categories |

n (%) |

|

Publication year |

2016–2017 |

2 (11.1) |

|

2018–2019 |

1 (5.6) |

|

2020–2021 |

3 (16.7) |

|

2022–2023 |

5 (27.8) |

|

2024–2025 |

7 (38.9) |

|

Participants |

Third-year students |

2 (11.1) |

|

Fourth-year students |

4 (22.2) |

|

Third- and fourth-year students |

10 (55.6) |

|

Others |

2 (11.1) |

|

Study design |

Descriptive survey |

16 (88.9) |

|

Quasi-experimental study |

1 (5.6) |

|

Qualitative study |

1 (5.6) |

|

Sample size |

0–50 participants |

1 (5.6) |

|

51–100 participants |

3 (16.7) |

|

101–150 participants |

5 (27.8) |

|

151–200 participants |

3 (16.7) |

|

Over 200 participants |

6 (33.3) |

|

Study setting |

Single university |

9 (50.0) |

|

Multiple universities |

9 (50.0) |

|

Clinical environment described |

Yes |

11 (61.1) |

|

No |

7 (38.9) |

Table 2.Key Variables Related to Clinical Practice Stress and Their Relationships in Included Studies (N=18)

|

No. |

Author (year) |

Participant year in program |

Clinical practice experience |

Clinical practice environment characteristics |

Key variables |

Relationships between variables/model explanation (%) |

|

A1 |

Cho (2025) |

Current & graduated students |

Y |

N/A |

COVID-19 stress, social connectedness, resilience, coping, clinical practice stress |

Clinical stress was positively associated with COVID-19 stress. Students with high COVID-19 stress were 6.65 times more likely to report clinical stress. |

|

A2 |

Kim (2024) |

3rd–4th |

Y |

N/A |

Transition shock, resilience, clinical practice stress |

Resilience mediated the relationship between transition shock and clinical stress (B=.655, p<.001; 95% CI=0.026–0.092). |

|

A3 |

Park and Yoo (2024) |

3rd–4th |

Y |

Type, region, number of practicums |

Maladaptive perfectionism, self-leadership, social support, clinical stress |

Clinical stress: perfectionism (+), self-leadership and social support (–)/model explained 43% of variance. |

|

A4 |

Lee and Hong (2024) |

3rd–4th |

Y |

N/A |

PMS, endocrine disruptor exposure |

Clinical stress: endocrine disruptor exposure (+), social support (–), academic year (+)/model explained 18% of variance. |

|

A5 |

Jeong and Park (2024) |

4th |

Y |

N/A |

Academic burnout, depression, clinical practice stress |

Clinical stress: burnout (+), depression (+)/model explained 75.6% of variance. |

|

A6 |

Yang (2024) |

3rd–4th |

Y |

Number of institutions, educational environment |

Clinical learning environment, clinical stress |

Clinical stress: departmental adaptation (–). |

|

A7 |

Shim (2024) |

4th |

Y |

N/A |

Online practice education, clinical stress |

Clinical stress reduced by questions about substitution of in-person practice, perception of online effectiveness, and complexity of pediatric care. |

|

A8 |

Kim (2023) |

3rd–4th |

Y |

Affiliated hospital (2 universities) |

Affiliated hospital, major satisfaction, housing type, clinical stress |

Higher stress was observed in students without affiliated hospital due to housing and other issues. |

|

A9 |

Kim et al. (2023) |

3rd |

Y |

Type of practicum hospital |

Teaching effectiveness, peer caring, clinical stress |

Clinical stress: peer caring (–), teaching effectiveness (–)/model explained 21.2% of variance. |

|

A10 |

Park (2023) |

3rd–4th |

Y |

N/A |

Online practicum experience, communication, clinical competence |

Clinical stress not significantly associated with communication or clinical performance. |

|

A11 |

Heo and Song (2023) |

3rd–4th |

Y |

N/A |

Verbal abuse, coping, major satisfaction, clinical stress |

Clinical stress: major satisfaction (–), coping (+), verbal abuse (not significant). |

|

A12 |

Lee (2022) |

4th |

Y |

Practicum subject, region, institution, department |

COVID-19 era, anxiety, health status, clinical stress |

Clinical stress: anxiety (+), health status (–)/model explained 21.8% of variance. |

|

A13 |

Kwak et al. (2021) |

3rd |

Y |

First practicum department, region |

Incivility, clinical learning environment, clinical stress |

Clinical stress: incivility (+), environment (–)/model explained 22.5% of variance. |

|

A14 |

Lee et al. (2021) |

3rd–4th |

Y |

Hospital size (tertiary, general, region) |

Satisfaction, sleep duration, sleep quality, quality of life, clinical stress |

Clinical stress: sleep quality, resilience (–)/model explained 50% of variance. |

|

A15 |

Koong et al. (2020) |

4th |

Y |

Difficulties in clinical practice, especially interpersonal issues |

Incivility, resilience, clinical stress |

Clinical stress: incivility (+), resilience (–)/model explained 41.6% of variance. |

|

A16 |

Kim and Park (2018) |

3rd–4th |

Y |

Role model: presence/absence |

Incivility, satisfaction, burnout, clinical stress |

Clinical stress: incivility (+), satisfaction (–), burnout (+)/model explained 38.4% of variance. |

|

A17 |

Jeong and Lee (2016) |

3rd–4th |

Y |

Practicum duration (8–9 weeks or 10+ weeks) |

Violence, resilience, emotional response, clinical stress |

Clinical stress: violence (+), emotional coping (+), emotional response (+), resilience (–)/model explained 18.1% of variance. |

|

A18 |

Yeom and Choi (2016) |

1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th |

N |

Hospital size (tertiary, general, region) |

Core nursing skills training, critical thinking, self-confidence, clinical stress |

Post-intervention: significant reduction in clinical stress. |

Table 3.Characteristics of Factors Related to Clinical Practice Stress (41 Factors Identified in 18 Studies) (N=41)

|

Categories |

Subcategories |

Main variables (study ID) |

|

Environmental factors (n=22) |

Clinical practice environment |

Violence [A11,A17], incivility [A13,A15,A16], transition shock [A2]*, non-affiliated hospital and housing [A8] |

|

Educational environment |

Core nursing skill education [A18], online practice [A7,A10], clinical learning environment [A6,A13] |

|

System/policy-related |

Departmental adaptation [A6,A9], frequency of outside placements [A3] |

|

Interpersonal |

Peer caring behavior [A9], senior–junior relationship improvement [A4,A6] |

|

Social support |

Social support [A3,A4,A13], social connectedness [A1] |

|

Instruction/teaching quality |

Academic burnout [A5], teaching effectiveness [A9] |

|

Emerging infection-related |

COVID-19 pandemic [A1,A12] |

|

Other |

Sleep [A14], endocrine disruptor exposure [A4] |

|

Individual factors (n=19) |

Coping and emotional regulation |

Coping strategies [A1,A3,A11,A17], emotional response [A17], emotional-focused coping [A17], maladaptive perfectionism [A3] |

|

Self-regulation |

Self-leadership [A3], self-confidence in performance [A18] |

|

Satisfaction and motivation |

Major satisfaction [A3,A11,A16] |

|

Psychological state |

Anxiety [A12], depression [A5], empathy [A11] |

|

Personality traits |

Resilience [A1,A2,A4,A15,A17] |

|

Physical health |

Health status [A12] |

|

Communication |

Communication [A10] |

|

Other |

Burnout [A5,A16]* |

REFERENCES

- 1. Park MS, You MJ. The effect of maladaptive perfectionism, self-leadership, and social support on nursing students' clinical practice stress. J Korea Soc Comput Inf. 2024;29(4):105-14. https://doi.org/10.9708/jksci.2024.29.04.105

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO global strategic directions for nursing and midwifery (2021-2025) [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2021 [cited 2023 May 10]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240033863

- 3. Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing Education (KABONE). 2023 Accreditation evaluation handbook for nursing education universities (1st & 2nd half). Seoul: KABONE; 2023.

- 4. Kwon IS, Seo YM. Nursing students' needs for clinical nursing education. J Korean Acad Soc Nurs Edu. 2012;18(1):25-33. https://doi.org/10.5977/jkasne.2012.18.1.025

- 5. Yoon S, Yeom HA. Development of the hybrid clinical practicum environment scale for nursing students. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2024;54(3):340-57. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.24016

- 6. Kim YK. The impact of clinical practice transition shock on clinical practice stress in nursing students: the mediating effect of resilience. J Health Care Life Sci. 2024;12(2):555-66. https://doi.org/10.22961/JHCLS.2024.12.2.555

- 7. Kim SG, Song UR. Effect of integrated simulation education on nursing students’ knowledge, clinical performance, and clinical reasoning competency. J Learn Cent Curric Instr. 2023;23(6):15-26. https://doi.org/10.22251/jlcci.2023.23.6.15

- 8. Hwang SJ. The relationship between clinical stress, self-efficacy, and self-esteem of nursing college students. J Korean Acad Soc Nurs Educ. 2006;12(2):205-13.

- 9. Lee AK, You HS, Park IH. Affecting factors on stress of clinical practice in nursing students. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2015;21(2):154-63. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2015.21.2.154

- 10. Kim SH, Lee JH, Jang MR. Factors affecting clinical practicum stress of nursing students: using the Lazarus and Folkman's stress-coping model. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2019;49(4):437-48. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2019.49.4.437

- 11. Choi HJ. The analysis of trends in domestic research on clinical practice stress of nursing students. J Learn Cent Curric Instr. 2021;21(5):355-67. https://doi.org/10.22251/jlcci.2021.21.5.355

- 12. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984.

- 13. Jung YH, Yang SH. A meta-analysis of variables related to clinical practice stress in Korean nursing students. J Learn Cent Curric Instr. 2023;23(19):841-65. https://doi.org/10.22251/jlcci.2023.23.19.841

- 14. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- 15. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- 16. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- 17. Park HJ, Jang IS. Stress, depression, coping styles and satisfaction of clinical practice in nursing students. J Korean Acad Soc Nurs Educ. 2010;16(1):14-23. https://doi.org/10.5977/jkasne.2010.16.1.014

- 18. Yang KH, Choi GY, Jo EH, Park S. Exploratory study for the improvement of clinical practice education in undergraduate nursing programs in Korea: Based on the review of clinical practice programs of three nursing colleges in the United States. J Korean Nurs Res. 2019;3(2):13-24. https://doi.org/10.34089/jknr.2019.3.2.13

- 19. Kim EY, Yang SH. Effects of clinical learning environment on clinical practice stress and anxiety in nursing students. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2015;21(4):417-25. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2015.21.4.417

- 20. Majrashi A, Khalil A, Nagshabandi EA, Majrashi A. Stressors and coping strategies among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: scoping review. Nurs Rep. 2021;11(2):444-59. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep11020042

- 21. Cho YM. Analysis of factors influencing clinical-practice stress among nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Ind Converg. 2025;23(2):143-51. https://doi.org/10.22678/JIC.2025.23.02.143

- 22. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Announcement of of the 2025 Nursing College Practical Education Support Project Implementation Contest (announcement no. 2025–172) [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2025 [cited 2025 March 20]. Available from: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10501010200&bid=0003&act=view&list_no=1484891

- 23. Ahn EK. The trends of the research on resilience in Korean nursing students: perspectives of convergence. J Korea Converg Soc. 2019;10(5):397-405. https://doi.org/10.15207/JKCS.2019.10.5.397

- 24. Kim KA. Development and effectiveness of non-face-to-face coaching-based university extracurricular programs: focusing on S Women’s University. Korean J General Edu. 2022;16(2):405-20. https://doi.org/10.46392/kjge.2022.16.2.405