Abstract

-

Purpose

This study aimed to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a therapeutic communication program based on King’s goal attainment theory, specifically designed for nurses providing care to patients with hematological oncology in a tertiary hospital setting.

-

Methods

A non-equivalent control group design was employed, involving 59 nurses (intervention group: 29, control group: 30) with experience in hematological cancer care. The therapeutic communication program, developed according to the theoretical constructs of King’s theory, consisted of eight weekly sessions. Outcome variables included problem-solving ability, communication self-efficacy, and interaction satisfaction. The effects of the intervention were analyzed using the independent- and paired-samples t-test as well as a Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

-

Results

In between-group comparisons of pre–post changes, communication self-efficacy increased significantly more in the intervention group than in the control group (p=.027). However, no significant between-group differences were found for problem-solving ability or interaction satisfaction. These findings suggest that the program effectively enhances therapeutic communication competencies among nurses in hematological oncology wards.

-

Conclusion

The therapeutic communication program significantly improved problem-solving ability, communication self-efficacy, and interaction satisfaction among nurses in the intervention group within the hematological oncology ward. This theory-based intervention provides an evidence-based framework for strengthening clinical nursing practice and education.

-

Key Words: Health communication; Hematologic neoplasms; Patient satisfaction; Self efficacy; Therapeutics

INTRODUCTION

Therapeutic communication refers to the process of interaction between nurses and patients aimed at achieving health-related goals, encompassing both verbal and non-verbal communication [

1]. This form of communication is essential for establishing trust, providing emotional support and stability, and contributing to the professional growth of nurses [

2]. Effective communication skills are especially critical in high-risk, high-stress environments where nurses carry substantial responsibility [

3]. However, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic has introduced additional obstacles to therapeutic communication, such as mask-related barriers and increased workload demands [

4].

In Korea, the incidence rates of blood cancers—including lymphoma, leukemia, and multiple myeloma—rose substantially by 39.60%, 27.68%, and 43.56%, respectively, in 2020 compared to 2010 [

5]. Despite this increase, research focusing on patients with blood cancer undergoing chemotherapy remains limited in the Korean context [

6]. Patients diagnosed with hematological malignancies frequently experience a heavy burden of physical and psychological symptoms—such as pain, mucositis, dyspnea, fatigue, nausea, constipation, and diarrhea—that can be as severe as, or even greater than, those faced by patients with advanced solid tumors [

7]. These patients require effective two-way communication regarding treatment plans and disease progression [

8]. Yet, existing therapeutic communication strategies are primarily designed to help healthcare providers in planning patient management [

9]. Therefore, a two-way therapeutic communication method that aligns with the needs of blood cancer patients is required. In a study by Abdellah Othman et al. [

10], nurses’ knowledge, skills, and service quality were significantly enhanced through a therapeutic communication program consisting of assessment, planning, implementation, and evaluation phases. Nonetheless, patients in clinical settings frequently express dissatisfaction with communication, often attributing this to a lack of empathy and caring behaviors from healthcare personnel [

2]. Accordingly, therapeutic communication between patients and nurses remains a critical component of patient-centered care [

4]. In this study, nursing goals were established through a therapeutic communication program applying King’s goal attainment theory, with a focus on interaction with researchers to achieve those goals.

Existing therapeutic communication strategies have been developed primarily to improve patient outcomes by addressing emotional and informational needs. However, limited research has examined strategies for enhancing the therapeutic communication abilities of nurses while simultaneously fostering mutual communication between patients and nurses [

9]. Studies have shown that nurses’ therapeutic communication skills are closely associated with patients’ trust and satisfaction. When nurses are able to accurately assess patient needs and intervene appropriately, trust within the nurse-patient relationship is strengthened [

11].

Furthermore, providing high-quality, person-centered care not only enhances nurses’ self-efficacy but also increases job satisfaction [

12]. Although research has examined therapeutic communication skills for nurses, including general nursing communication models [

1] and those specific to psychiatric nursing [

13], a significant gap remains in the development and evaluation of structured communication programs specifically tailored to the emotionally complex and clinically demanding environments of hematological oncology wards. A study applying Hildegard Peplau’s Interpersonal Nursing Theory to therapeutic communication emphasized key components such as empathy, trust, rapport, and the sub-factors of power-sharing [

14]. Because therapeutic communication is inherently grounded in interaction, the use of King’s goal attainment theory may play a pivotal role in strengthening nurses’ therapeutic communication skills.

King’s goal attainment theory emphasizes collaboration between nurses and patients to achieve health goals through mutual interaction, serving as the theoretical foundation for this study. The theory involves problem assessment, goal setting, and agreement on the means to achieve those goals through continuous interaction [

15]. The primary nursing objective under goal attainment theory is to ensure that nurses and patients identify problems and disabilities together, establish mutual goals, and work collaboratively to reach the final outcome through ongoing interaction [

16]. Prior applications of the theory have included group counseling and fall prevention programs [

16,

17]. However, to date, no intervention studies have applied the theory specifically to therapeutic communication programs for nurses in hematological oncology wards. Moreover, patients with hematological cancers often face prolonged, cyclical treatment regimens and unpredictable disease progression, which necessitate that nurses adopt adaptive and empathetic communication strategies grounded in both theory and clinical practice.

Accordingly, this study aims to develop a therapeutic communication program for nurses caring for patients with hematological cancer, based on King’s goal attainment theory. In addition to verifying the effectiveness of the intervention, the study seeks to establish its feasibility for clinical application and to explore its potential integration into in-service training and nursing education curricula as a sustainable, evidence-based communication model.

This study aimed to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a therapeutic communication program based on King’s goal attainment theory for nurses working in hematological oncology wards.

We hypothesize that the scores for problem-solving ability (H1), communication self-efficacy (H2), and interaction satisfaction (H3) will change more in the intervention group than in the control group.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This study employed a non-equivalent control group design to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a therapeutic communication program for nurses caring for patients with hematological cancer. The intervention was designed based on the theoretical framework of King’s goal attainment theory, which emphasizes mutual goal setting and interaction between nurses and patients. This study was reported in accordance with the TREND (Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs) statement.

2. Study Participants

Participants were recruited from the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, a tertiary hospital in Seoul. Eligible participants were nurses with clinical experience in hematological oncology care who voluntarily agreed to participate. The inclusion criteria were: (1) registered nurses with at least six months of clinical experience, (2) experience providing care for patients with hematological malignancies, (3) no prior participation in communication training programs, and (4) understanding of the study purpose and provision of written informed consent.

Several measures were taken to minimize contamination due to non-random assignment. The control group was selected from a different floor to reduce interaction with the intervention group. Both groups were separated in terms of medical facility environment and nursing education to limit overlap. In addition, their schedules were adjusted to prevent cross-group interaction. Each group was assigned a dedicated researcher to ensure independent management. Representative nurses from the two floors were randomly selected by lottery and assigned to the intervention or control group. Data collection and analysis for each group were conducted independently to prevent potential influence between groups.

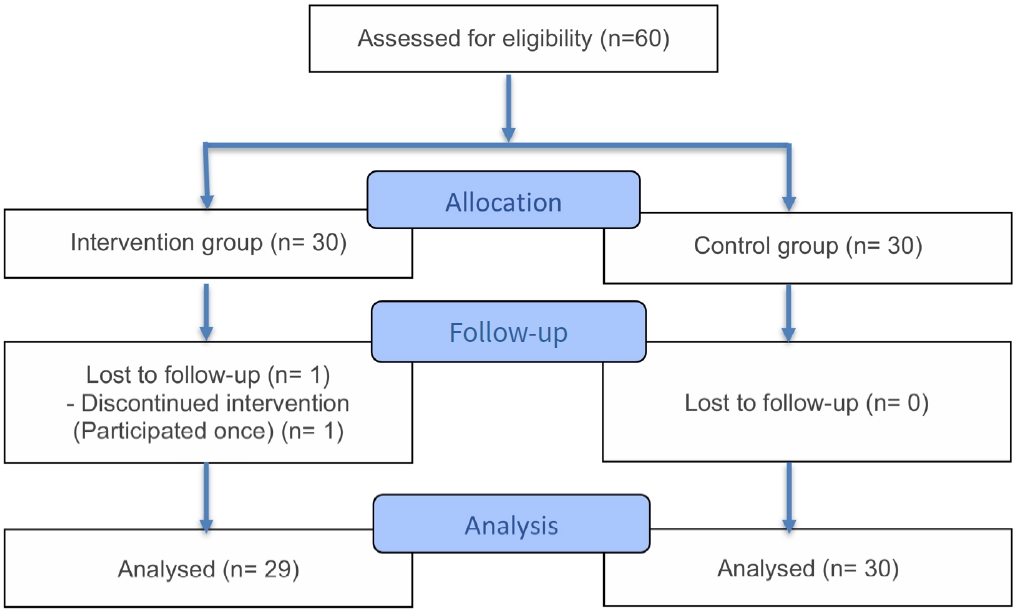

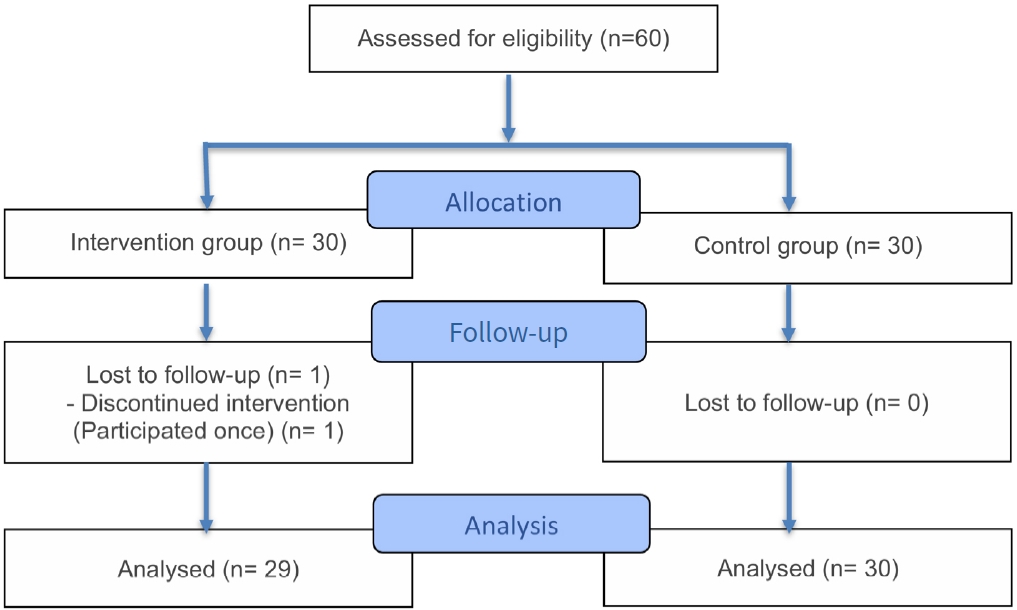

The required sample size was calculated using G*Power 3.1.9.7. Based on a prior study [

18], the calculated effect size (ES) was .80, the significance level was set at .05, and the statistical power at .80. An independent two-tailed t-test indicated that at least 52 participants (26 per group) were required. To account for a 10% dropout rate, 60 participants were initially recruited (30 per group). However, one participant from the intervention group withdrew, resulting in a final sample of 59 participants (29 in the intervention group and 30 in the control group) (

Figure 1).

1) Problem-solving ability

Nurses’ problem-solving ability was measured using a tool developed by Heppner and Petersen [

19] and translated by Chun [

20]. The tool consisted of 21 items scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“very much so”). Higher scores indicated greater problem-solving ability. The internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α) was .89 in the original study, .90 in Chun’s [

20] study, and .82 in the present study.

2) Communication self-efficacy

Communication self-efficacy was measured using the Counseling Self-Estimate Inventory (COSE) developed by Larson et al. [

21] and adapted by Hong and Choi [

22]. The version used in this study was further modified and validated for nurses by Park et al. [

23]. It consisted of 37 items scored on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 6 (“very much so”). Higher scores indicated greater communication self-efficacy. Cronbach’s α was .93 in the original study, .74 in Park et al.’s study [

23], and .91 in this study.

3) Interaction satisfaction

Interaction satisfaction was assessed using a tool modified and supplemented from Lim’s [

24] study and later used in Kim’s [

25] research. The tool contained nine items measured on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“very much so”). Higher scores indicated greater satisfaction with interpersonal interactions. Cronbach’s α was .87 in Kim’s [

25] study and .86 in this study.

1) Contents of the therapeutic communication program

The therapeutic communication program was developed based on King’s goal attainment theory and structured according to the processes of problem assessment, goal setting, composition, and interaction (

Table 1). A prior qualitative study on therapeutic communication among nurses in a hematological oncology ward [

26] confirmed the need for such a program. As a result, problem-solving ability, communication self-efficacy, and interaction satisfaction were selected as outcome variables. Literature on human understanding and communication [

27], along with studies on therapeutic communication [

2,

10,

28], was reviewed to develop program content and case examples. Group activities consisted of lectures, discussions, and sharing of experiences, while individual activities included emotional support and encouragement through in-hospital group messages. A therapeutic communication pamphlet was developed by one professor from the Department of Nursing, two head nurses, and four nurses with more than 10 years of experience. Content validity was assessed and confirmed.

The first session focused on “problem assessment and goal setting.” The researcher introduced the therapeutic communication program and schedule and identified communication problems experienced by nurses. From the second to seventh sessions, nurses and researchers engaged in interactive activities. Specifically, the second and third sessions focused on “understanding and improving therapeutic communication.” These sessions included education, experience sharing using pamphlets, and discussions on response strategies for various situations. They also incorporated peer support, encouragement, and internal messages to promote continued participation. The fourth and fifth sessions addressed “Improving interaction satisfaction,” consisting of lectures and educational sessions on mutual satisfaction and shared interaction experiences. In the fifth session, the 5A clinical counseling framework (Ask–Advise–Assess–Assist–Arrange) [

29] was applied. The sixth session provided feedback on interaction experiences and included discussion of applying the 5A steps. The seventh session focused on “improvement of therapeutic communication ability.” Nurses practiced therapeutic communication behaviors, compared outcomes, and shared opinions to enhance mutual satisfaction. Peer support needs were also discussed. The eighth session centered on “continuation of actions to improve therapeutic communication ability.” Goals were reviewed, and obstacles were identified (

Table 1).

2) Program implementation and progress

The study was conducted over eight weeks, from October 2022 to December 2022. Surveys were administered before and after the eight-week program.

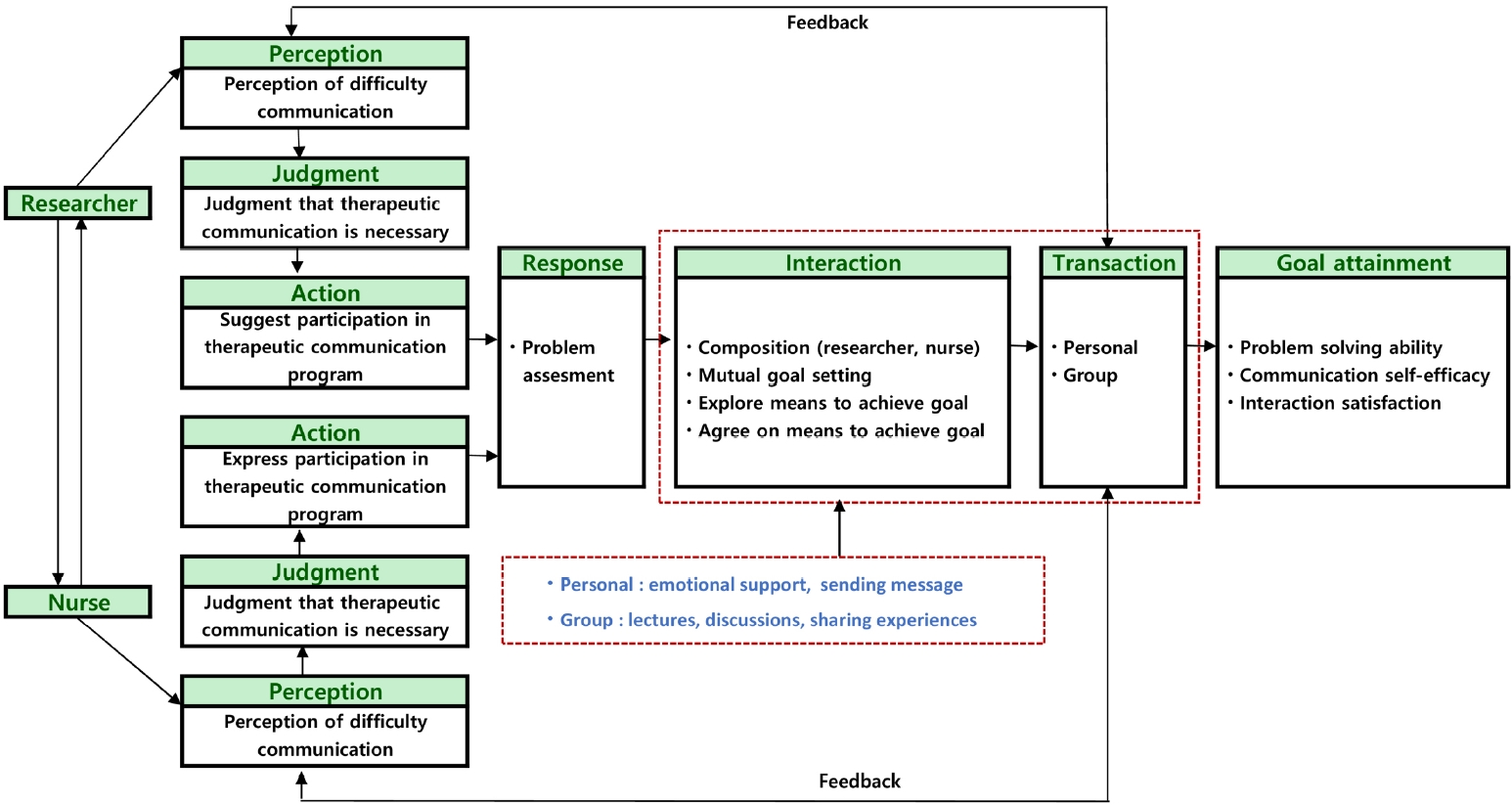

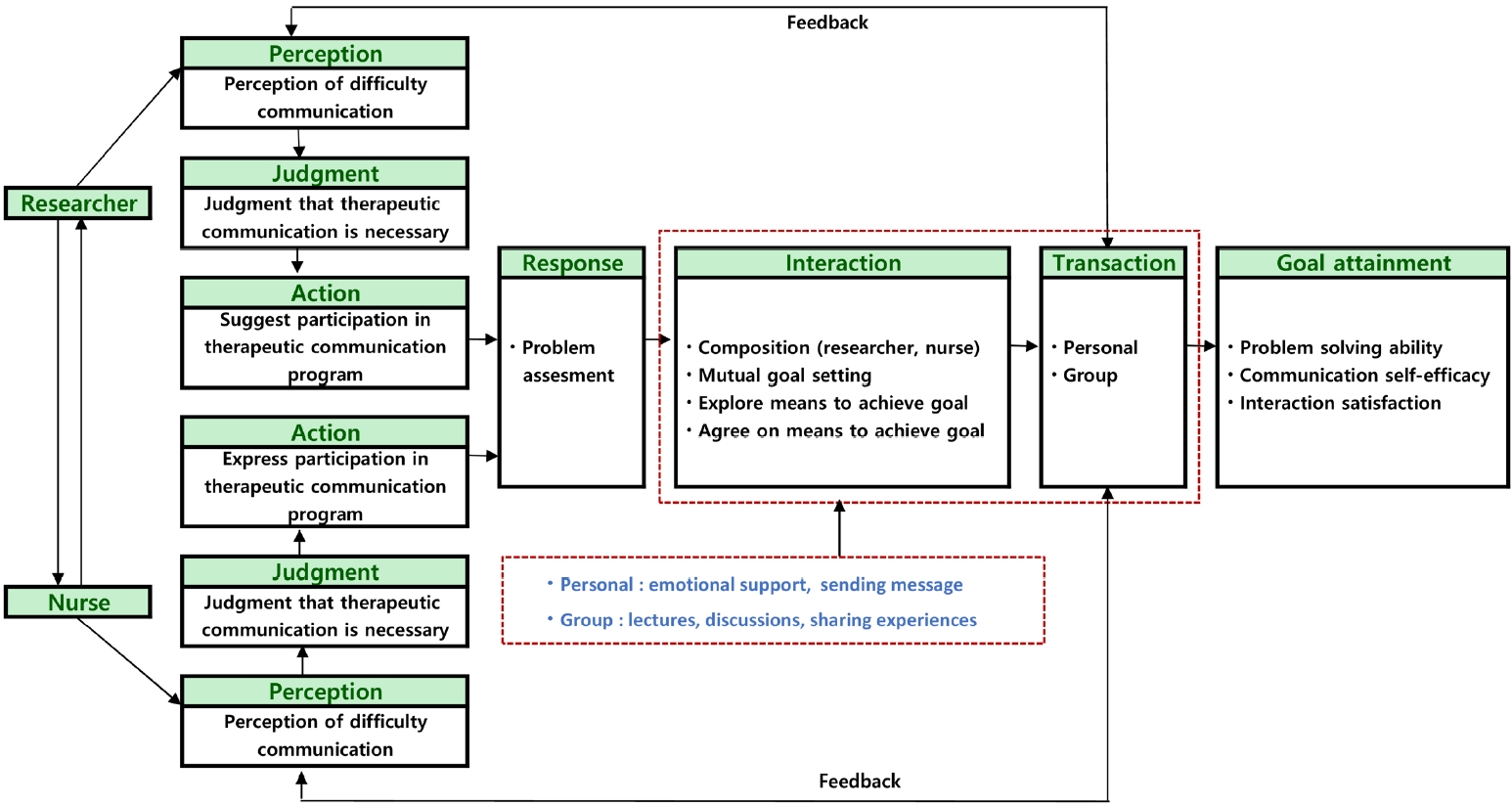

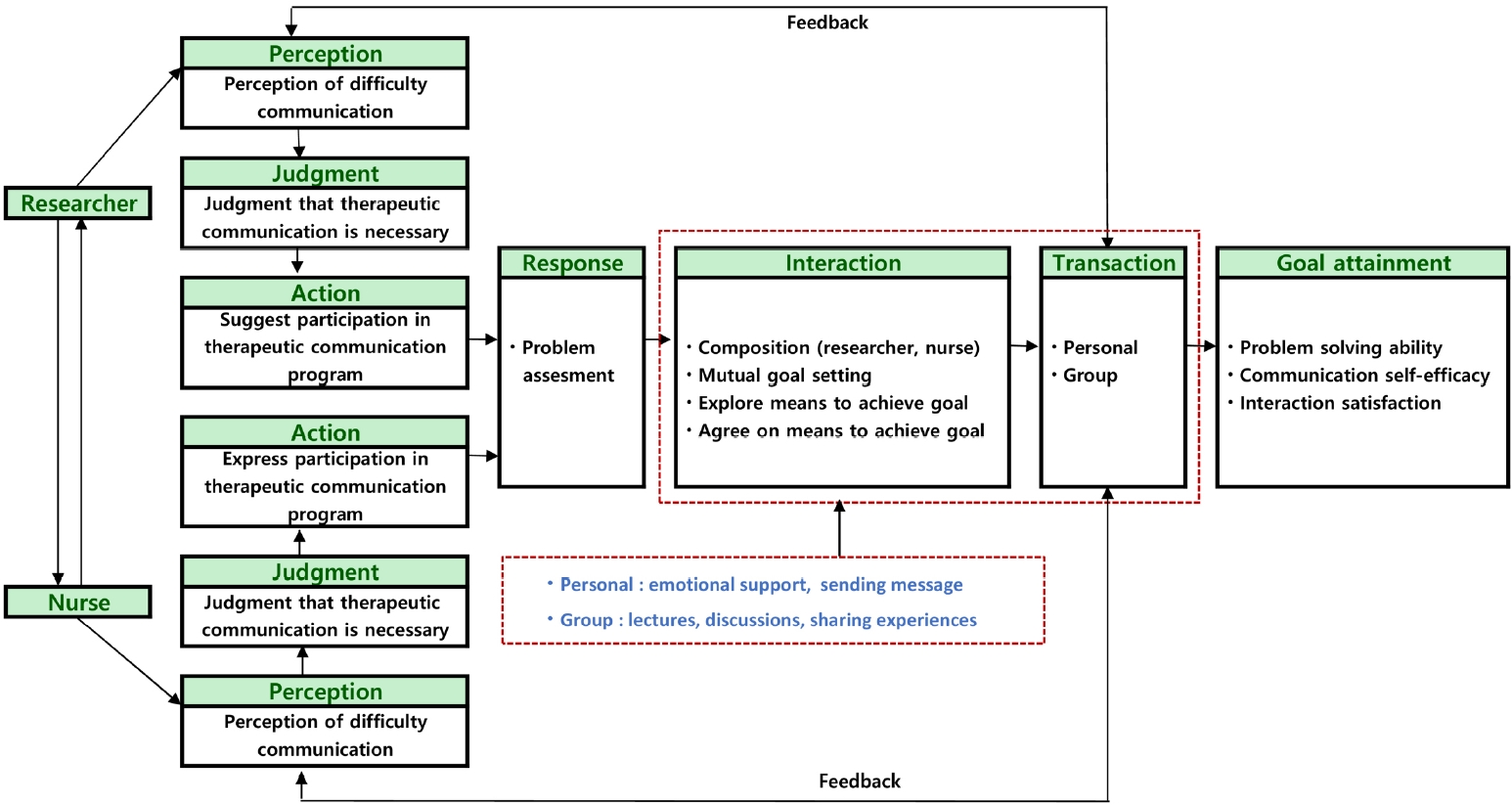

A conceptual framework based on King’s goal attainment theory was established to evaluate the effectiveness of the therapeutic communication program among nurses caring for patients with hematological cancer (

Figure 2).

The program emphasized mutual decision-making between the researcher and participants, reflecting the interactive nature of King’s theory. Its objectives were to enhance problem-solving ability, communication self-efficacy, and interaction satisfaction.

The therapeutic communication program was conducted over an eight-week period, with each session lasting one hour, following the structure of previous studies [

30]. During the introductory phase (week 1), participants were introduced to the program’s structure and objectives. The development phase (weeks 2–7) included educational pamphlets, lectures, group discussions, experience sharing sessions, peer feedback, and motivational messages delivered via in-hospital communication platforms. In the final phase (week 8), participants reviewed program content, reaffirmed goals, and received reinforcement and encouragement through weekly intra-hospital messages. Both individual activities (e.g., colleague support, experience sharing, self-reflection) and group activities (e.g., role play, discussion, collective experience sharing) were incorporated throughout the intervention (

Table 1). During the program, nurses discussed with the researcher the communication difficulties they had experienced in the previous week. The researcher worked continuously with each nurse to improve therapeutic communication skills by providing counseling and feedback. Particularly during weeks 2 to 7, feedback was provided to participants at each session, and based on this feedback, interactions and transactions were repeated over the following week to reapply strategies in therapeutic communication.

Before the start of the study, an announcement was made to the nursing department of the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, and nurses who volunteered were recruited. For the pre-survey, research assistants explained the study’s purpose, procedures, and data collection methods, and written consent was obtained. Surveys were conducted in a private setting to ensure participant convenience. Participants were informed that confidentiality and anonymity were guaranteed, that data would be used solely for research purposes, and that participation was voluntary, with the option to withdraw at any time without penalty. Both the intervention and control groups completed the same questionnaire, which required approximately 20 minutes. To ensure blinding, research assistants—rather than the researchers—administered the surveys after being trained on the study’s objectives, content, and procedures. The control group received no intervention during the study period. After the intervention was completed, the control group was provided with the same educational materials on therapeutic communication as those given to the intervention group.

6. Ethical Considerations

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, (approval No. KC22EASI0575). Participants were informed of the study’s purpose, procedures, and voluntary nature. They were assured that they could withdraw at any time without penalty and that refusal to participate carried no disadvantages. Confidentiality and anonymity of all collected data were guaranteed, and the data were used solely for research purposes. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. A small token of appreciation was provided after completion of data collection.

7. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The chi-square test (χ² test) and the independent-samples t-test were performed to confirm the baseline homogeneity of general characteristics, and the independent-samples t-test was used to check the homogeneity of primary variables. The independent-samples t-test was performed to evaluate the significance of differences between the post-scores of the intervention group and those of the control group. The paired-sample t-test was conducted to assess whether the differences between the pre- and post-tests were significant in the intervention group and the control group. Changes in interaction satisfaction were further analyzed using Wilcoxon’s signed-rank test. The significance level of p<.05 was used for all statistical tests.

RESULTS

1. Participant Characteristics and Homogeneity Testing

A pretest of homogeneity was conducted with 29 participants in the intervention group and 30 participants in the control group to examine general characteristics and baseline values of the dependent variables. The results showed no significant differences, confirming that both groups were homogeneous at baseline (

Table 2).

1) Problem-solving ability

The pre–post change did not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups (between-group mean difference=0.08, standard deviation [SD]=0.09; t=0.86; p=.195). Therefore, the hypothesis that the intervention group would show a greater improvement in problem-solving ability was not supported.

2) Communication self-efficacy

The pre–post change was significantly greater in the intervention group than in the control group (between-group mean difference=0.21, SD=0.11; t=1.96; p=.027). This result supports the hypothesis that the intervention group would demonstrate a greater increase in communication self-efficacy.

3) Interaction satisfaction (changes in score)

The pre–post change in interaction satisfaction did not differ significantly between the intervention and control groups (between-group mean difference=0.11, SD=0.14; t=0.81;

p=.210). Therefore, the hypothesis that the intervention group would show a greater improvement was not supported (

Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Various educational models, such as Communication Skills Training, have been implemented to improve communication competencies. However, these models are primarily designed for medical counseling and have limitations when applied to nursing practice [

31]. Moreover, most clinical education is delivered in a didactic manner, lacking interactive or experiential elements necessary to motivate learners and develop the practical skills required for managing complex patient situations [

32].

The program developed in this study, based on King’s goal attainment theory, emphasizes interaction between nurses and patients to identify problems, set goals, and work collaboratively toward achieving those goals [

17]. By tailoring the approach to the individual goals of each patient, the program enhances communication and promotes patient participation in treatment. Interaction between patient and nurse improves the quality of communication throughout the goal attainment process, strengthening self-efficacy and treatment adherence. Furthermore, the program encourages patients to record their goals and exchange feedback, making communication richer and more effective through multiple methods.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of interventions based on goal attainment theory have demonstrated applicability across diverse domains, including health promotion (ES=0.76), goal setting and health contracts (ES=0.35), fall prevention (ES=1.25), counseling and education (ES=0.72), and parent participation (ES=1.35). These findings suggest that the theory can be flexibly applied depending on the patient’s situation [

33].

This study found that the program exerted significant positive effects on nurses’ problem-solving abilities, communication self-efficacy, and interaction satisfaction. Following the intervention, nurses in the experimental group demonstrated marked improvements in communication skills. These findings are consistent with Kim and Sim [

12], who reported that clinical nurses’ communication skills have a direct impact on problem-solving ability.

In this program, problem-solving strategies were taught in stages, and case scenarios reflecting real therapeutic communication situations were integrated into the curriculum. Participants developed empathy and perspective-taking skills through role-plays, acting as patients, nurses, and observers. This approach proved particularly valuable in scenarios such as communicating with non-cooperative patients before cancer treatment. The training also addressed providing feedback in challenging clinical situations and using open- and closed-ended questions appropriately. This teaching method aligns with prior simulation-based education research that sought to enhance the clinical competencies of new nurses [

22]. It is also notable that less experienced nurses may find it difficult to express their opinions confidently or may lack clinical expertise due to heavy workloads [

12].

In a randomized controlled study of problem-solving and decision-making skills [

34], significant improvements in problem-solving ability were observed only in the experimental group. By contrast, improvements were noted in both the intervention and control groups in this study, with no statistically significant between-group differences. Despite efforts to minimize environmental contamination—such as separating nursing units and reducing shared educational influences—problem-solving ability also improved in the control group. This finding suggests that controlling external factors in non-equivalent control group designs is challenging and may influence results. Furthermore, 10 more participants in the control group had over five years of hospital experience compared to the intervention group, where 86% had fewer than five years of experience. The greater experience among control participants may have contributed to improvements in problem-solving ability over time. Additionally, motivational effects of research participation and informal information sharing within the ward may also have played a role.

Communication self-efficacy significantly improved among nurses in the intervention group, consistent with previous research [

35]. Effective nurse-patient communication is critical for ensuring the efficiency and quality of care and has been shown to positively influence patients’ perceptions of health, treatment satisfaction, and clinical outcomes [

4]. However, current communication practices are often shaped by individual nurse characteristics and educational background, with few standardized competencies established for basic nurse-patient communication [

4]. Structured communication education, as implemented in this study, can enhance nurses’ self-confidence, self-efficacy, and capacity for patient-centered care [

2]. By integrating scenario-based role-plays, structured reflection, and video observation, the program facilitated measurable gains in self-efficacy.

In this study, interaction satisfaction improved significantly within the intervention group; however, no statistically significant differences were found between groups. This contrasts with prior research [

17], which reported improvements exclusively among intervention participants. The intervention was grounded in evidence that patient-centered communication—which emphasizes respect for individual preferences, shared decision-making, and patient engagement—enhances quality of care [

28]. Accordingly, it incorporated opportunities to share therapeutic communication experiences, structured feedback to strengthen interpersonal interactions, and counseling and encouragement to address challenges encountered in clinical practice. These elements may have contributed to the observed within-group improvements. Meanwhile, environmental factors such as natural improvement over time in the control group and institution-level training in interpersonal interaction may have operated in parallel, potentially explaining the lack of significant between-group differences.

This program described in this study enhances the professional expertise of nurses in the hematological oncology ward and promotes communication and treatment engagement through patient interactions. The program is expected to increase patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes, particularly for those undergoing long-term therapy. Moreover, digital systems can facilitate continuous monitoring of patient conditions, optimizing treatment effectiveness even without direct contact. The provision of emotional support is also critical, as it helps reduce anxiety and stress, strengthens psychological stability, and promotes a more positive attitude toward treatment.

This study holds significance both theoretically and practically. First, it empirically validates King’s goal attainment theory as a robust and applicable framework for clinical nursing practice, demonstrating that theoretical models can be effectively translated into practice to strengthen essential communication competencies.

Second, the therapeutic communication program developed here represents a structured, evidence-based intervention suitable for application in both clinical practice and nursing education, including continuing professional development. Its modular and stepwise design supports scalability across various institutional contexts.

Third, improving nurses’ communication skills may indirectly benefit patient-reported outcomes, such as satisfaction, adherence to treatment, and overall health status. This program therefore has potential as a strategic intervention to advance patient-centered care and improve clinical outcomes. Future research should empirically examine these patient-related effects.

Fourth, cultural characteristics of Korean nursing practice—such as time constraints and norms surrounding emotional expression—can pose challenges to therapeutic communication. This program accounted for such cultural particularities, underscoring the need for cross-cultural research to evaluate its adaptability and effectiveness in diverse healthcare systems.

This study has several limitations. First, it was conducted in a single tertiary general hospital, which restricts the generalizability of findings. Future research should include multiple institutions and employ randomized designs to improve external validity. Second, the non-randomized control group design raises the possibility that external factors contributed to improvements in the control group despite efforts to minimize contamination. Future studies should adopt randomized controlled designs or use additional strategies to reduce contamination for more accurate evaluation. Third, the study measured only short-term effects over an eight-week intervention. Longitudinal follow-up and systematic re-education are necessary to determine long-term benefits. Finally, interaction satisfaction was assessed solely from the nurses’ perspective. Future studies should incorporate patient-centered interventions and evaluate satisfaction from both nurses and patients to provide a more comprehensive understanding of program effectiveness.

CONCLUSION

This study developed and empirically validated a therapeutic communication program for nurses in hematological oncology wards, grounded in King’s goal attainment theory. Within the intervention group, problem-solving ability, communication self-efficacy, and interaction satisfaction improved significantly. However, in between-group comparisons, only communication self-efficacy was significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group. These findings indicate that strengthening interactional processes, such as mutual perception, shared goal setting, and structured feedback, may be particularly effective in enhancing nurses’ communication self-efficacy, a core competency in oncology nursing. The program also provides a practical model for in-service training and continuing professional development in the emotionally demanding context of hematological oncology. By embedding patient-centered, goal-oriented communication into routine care, it narrows the gap between theory and practice. Ultimately, this program may help strengthen nurses’ capacity for holistic care in increasingly complex healthcare environments.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and/or design acquisition - HL and BMP; analysis - HL and BMP; interpretation of the data - HL, BMP, HK (Heeju Kim), JK and HK (HyunJung Kim); drafting or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content - HL and BMP; and literature search - HL and BMP.

-

FUNDING

This study was supported by the research fund of Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital, the Catholic University of Korea in 2023.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors would like to thank all the participants of the study.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Figure 1.

Figure 2.Conceptual framework of a therapeutic communication program based on King's goal attainment theory.

Table 1.Therapeutic Communication Program Based on King's Goal Attainment Theory

|

Procedure |

Theme |

Goal |

Transaction |

Contents |

Time (min) |

|

Problem assessment and mutual goal setting |

Introduction and mutual goal setting |

Check the problem and goal setting |

Individual |

Introduction and schedule of the TC program |

20 |

|

Identification of TC problems experienced by nurses |

|

Group |

Exchange of opinions among researchers and nurses about TC problems, and mutual goal setting |

40 |

|

Sharing difficulties and concerns about TC and encouragement of continued participation in the program |

|

Composition (researcher, nurse) and interaction |

Understanding and improving TC |

Understand and practice the TC |

Individual |

Encouragement of continued participation in TC programs and in-house messaging |

20 |

|

Peer support for therapeutic communication |

|

Group |

Education through TC pamphlet |

40 |

|

1) The concept of TC, obstacles, and precautions |

|

2) Communication in nursing settings: patients, older adults, and families |

|

3) Types of therapeutic communication: accepting, inducing, clarifying, encouraging, encouraging explanation, encouraging expression of feelings, exploring, focusing, planning actions, leading, informing, building awareness, observe, silence, offer cooperation, summarize, restate, check information |

|

4) Examples of therapeutic communication contexts: |

|

① TC with uncooperative patients before starting chemotherapy |

|

② TC with patients hospitalized after the first diagnosis of hematological cancer |

|

③ TC for patients with high anxiety after first diagnosis |

|

④ TC with an end-of-life blood cancer patient |

|

⑤ Communication with black consumers |

|

⑥ Communication with the patient after surgery |

|

5) Problem-solving skills: problem identification and definition, problem analysis, solution development, best solution analysis and selection, implementation, and evaluation |

|

6) Communication self-efficacy: definition, checklist for improving self-efficacy, role play by situation |

|

Sharing the experience of therapeutic communication |

|

Discussing therapeutic communication response strategies for each situation |

|

Composition (researcher, nurse) and interaction |

Understanding and improving TC |

Understand and practice the TC |

Individual |

Encouragement for continued participation in TC Programs and in-house messaging |

20 |

|

Experiences of peer support for TC in the past week |

|

Group |

Sharing difficulties with TC experienced in the past week |

40 |

|

Delivery of feedback on TC experience by situation |

|

Composition (researcher, nurse) and interaction |

Improving interaction satisfaction |

Check the TC problem |

Individual |

Encouragement for continued participation in the TC program and sending in-house messaging |

10 |

|

The field of peer support experienced last week. Checking for disadvantages |

|

Group |

Identification of individual problems in TC experienced |

50 |

|

Delivery of feedback for TC by situation |

|

Composition (researcher, nurse) and interaction |

Improving interaction satisfaction |

Improvement of therapeutic communication ability through interaction |

Individual |

Mutual satisfaction education in TC |

10 |

|

1) Checking items for emotional exchange, interaction process, and mutual satisfaction |

|

Education and internal messaging on the importance of interaction for TC |

|

Group |

Sharing experiences of interaction in TC |

50 |

|

Training TC using the 5A level |

|

1) Ask: the researcher proceeds with questions about TC to the nurse |

|

2) Advise: brief information about the TC skills of nurses and individualized advice |

|

3) Assess: identification of personal characteristics for TC |

|

4) Assist: provides assurance and support for action for TC |

|

5) Arrange: support and encouragement to maintain TC |

|

Composition (researcher, nurse) and interaction |

Improving interaction satisfaction |

Improvement of therapeutic communication ability through interaction |

Individual |

Encouragement for continued participation in the TC program and sending in-house messaging |

20 |

|

Counseling and encouragement about the interaction difficulties experienced in the past week |

|

Group |

Delivering feedback on interactive experiences in TC |

40 |

|

Sharing experience of TC ability and delivering feedback using 5A level |

|

Composition (researcher, nurse) and interaction |

Improving TC skills |

Improvement of skill practice TC through individual |

Group |

Comparison of TC behaviors that are well implemented and those that are not |

60 |

|

Sharing opinions to improve TC skills and mutual satisfaction |

|

Expression of opinions where peer support is needed to improve TC |

|

Continuing TC skills |

Improvement of skill practice TC through individual |

Group |

Checking the goals set through the TC program |

60 |

|

Identification of problems and obstacles |

|

Reminder of the importance of nurse-patient interaction even after the study is over |

|

Encouragement to continue TC |

Table 2.Homogeneity Test of General Characteristics between Groups (N=59)

|

Variables |

Categories |

n (%) or M±SD |

χ2 or t |

p

|

|

IG (n=29) |

CG (n=30) |

Total |

|

Age (year) |

|

27.79±4.03 |

29.63±4.78 |

28.73±4.45 |

–1.60 |

.116 |

|

Married |

No |

22 (75.9) |

23 (76.7) |

45 (76.3) |

0.01 |

.942 |

|

Yes |

7 (24.1) |

7 (23.3) |

14 (23.7) |

|

|

|

Education level |

Bachelor |

27 (93.1) |

26 (86.7) |

53 (89.8) |

1.73 |

.422 |

|

≥Master’s degree |

2 (6.9) |

4 (13.3) |

6 (10.2) |

|

|

|

Hematological oncology ward work experience |

<5 years |

25 (86.2) |

20 (66.7) |

45 (76.3) |

6.13 |

.106 |

|

≥5 years |

4 (13.8) |

10 (33.3) |

14 (23.7) |

|

|

|

Problem-solving ability |

3.36±0.36 |

3.43±0.36 |

- |

–0.75 |

.456 |

|

Communication self-efficacy |

4.07±0.49 |

3.94±0.38 |

- |

1.16 |

.251 |

|

Interaction satisfaction |

3.77±0.48 |

3.67±0.60 |

- |

0.73 |

.471 |

Table 3.Effects of the Therapeutic Communication Program between Groups (N=59)

|

Variables |

Time |

M±SD |

t |

p

|

|

IG (n=29) |

CG (n=30) |

Δ(IG−CG) |

|

Problem-solving ability |

Pre |

3.36±0.36 |

3.43±0.36 |

–0.07±0.36 |

–0.75 |

.456 |

|

Post |

3.96±0.20 |

3.96±0.16 |

0.00±0.18 |

0.15 |

.885 |

|

Pre–post difference |

0.60±0.29 |

0.52±0.39 |

0.08±0.09 |

0.86 |

.195 |

|

t |

11.05 |

7.43 |

|

|

|

|

p

|

<.001 |

<.001 |

|

|

|

|

Communication self-efficacy |

Pre |

4.07±0.49 |

3.94±0.38 |

0.13±0.44 |

1.16 |

.251 |

|

Post |

4.29±0.56 |

3.95±0.51 |

0.34±0.54 |

2.45 |

.017 |

|

Pre–post difference |

0.22±0.49 |

0.01±0.31 |

0.21±0.11 |

1.96 |

.027 |

|

t |

2.42 |

0.17 |

|

|

|

|

p

|

.022 |

.865 |

|

|

|

|

Interaction satisfaction |

Pre |

3.77±0.48 |

3.67±0.60 |

0.10±0.54 |

0.73 |

.471 |

|

Post |

4.08±0.52 |

3.87±0.61 |

0.21± 0.57 |

1.47 |

.146 |

|

Pre–post difference |

0.31±0.45 |

0.20±0.61 |

0.11±0.14 |

0.81 |

.210 |

|

Z |

3.72 |

1.80 |

|

|

|

|

p

|

<.001 |

.083 |

|

|

|

REFERENCES

- 1. McCarthy B, O'Donovan M, Trace A. A new therapeutic communication model "TAGEET" to help nurses engage therapeutically with patients suspected of or confirmed with COVID-19. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(7-8):1184-91. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15609

- 2. Atashzadeh-Shoorideh F, Mohtashami J, Farhadzadeh M, Sanaie N, Zadeh EF, Beykmirza R, et al. Humanitarian care: facilitator of communication between the patients with cancer and nurses. Nurs Pract Today. 2021;8(1):70-8. https://doi.org/10.18502/npt.v8i1.4493

- 3. Loh KP, Tsang M, LeBlanc TW, Back A, Duberstein PR, Mohile SG, et al. Decisional involvement and information preferences of patients with hematologic malignancies. Blood Adv. 2020;4(21):5492-500. https://doi.org/10.1182/bloodadvances.2020003044

- 4. Vitale E, Giammarinaro MP, Lupo R, Archetta V, Fortunato RS, Caldararo C, et al. The quality of patient-nurse communication perceived before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: an Italian pilot study. Acta Biomed. 2021;92(S2):e2021035. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v92iS2.11300

- 5. National Cancer Center. Annual report of cancer statistics in Korea in 2020 [Internet]. Goyang: National Cancer Center; 2022 [cited 2025 April 1]. Available from: https://ncc.re.kr/cancerStatsView.ncc?bbsnum=638&searchKey=total&searchValue=&pageNum=1

- 6. Kim GE, Song JE, You MA, Park JH. Symptom experience, social support, and quality of life in patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing chemotherapy. Asian Oncol Nurs. 2022;22(1):29-36. https://doi.org/10.5388/aon.2022.22.1.29

- 7. LeBlanc TW, El-Jawahri A. When and why should patients with hematologic malignancies see a palliative care specialist? Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2015;2015:471-8. https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2015.1.471

- 8. LeBlanc TW, Baile WF, Eggly S, Bylund CL, Kurtin S, Khurana M, et al. Review of the patient-centered communication landscape in multiple myeloma and other hematologic malignancies. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(9):1602-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2019.04.028

- 9. Pavlova S. Therapeutic communication in clinical practice. J IMAB. 2024;30(2):5509-12. https://doi.org/10.5272/jimab.2024302.5509

- 10. Abdellah Othman A, Abd El Fattah MA, Hassan El-Sayed Mahfouz H. Effect of therapeutic communication educational program for nurses on their nursing care quality. J Nurs Sci Benha Univ. 2023;4(1):270-87. https://doi.org/10.21608/jnsbu.2023.274780

- 11. Wu Y. Empathy in nurse-patient interaction: a conversation analysis. BMC Nurs. 2021;20(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00535-0

- 12. Kim AY, Sim IO. Communication skills, problem-solving ability, understanding of patients' conditions, and nurse's perception of professionalism among clinical nurses: a structural equation model analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(13):4896. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134896

- 13. Joung J, Park Y. Exploring the therapeutic communication practical experience of mental health nurses. J Korean Acad Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2019;28(4):321-32. https://doi.org/10.12934/jkpmhn.2019.28.4.321

- 14. Mersha A, Abera A, Tesfaye T, Abera T, Belay A, Melaku T, et al. Therapeutic communication and its associated factors among nurses working in public hospitals of Gamo zone, southern Ethiopia: application of Hildegard Peplau's nursing theory of interpersonal relations. BMC Nurs. 2023;22(1):381. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-023-01526-z

- 15. King IM. King's conceptual system, theory of goal attainment, and transaction process in the 21st century. Nurs Sci Q. 2007;20(2):109-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318407299846

- 16. Jeong IJ, Kim SJ. Effects of group counseling program based on goal attainment theory for middle school students with emotional and behavioral problems. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2017;47(2):199-210. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2017.47.2.199

- 17. Park BM. Development and effect of a fall prevention program based on King's theory of goal attainment in long-term care hospitals: an experimental study. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(6):715. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060715

- 18. Kim YH, Choi YS, Jun HY, Kim MJ. Effects of SBAR program on communication clarity, clinical competence and self-efficacy for nurses in cancer hospitals. Korean J Rehabil Nurs. 2016;19(1):20-9. https://doi.org/10.7587/kjrehn.2016.20

- 19. Heppner PP, Petersen CH. The development and implications of a personal problem-solving inventory. J Couns Psychol. 1982;29(1):66-75. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.29.1.66

- 20. Chun SK. The social skills training for social adjustment of the schizophrenic patients. Ment Health Soc Work. 1995;12(2):33-50.

- 21. Larson LM, Suzuki LA, Gillespie KN, Potenza MT, Bechtel MA, Toulouse AL. Development and validation of the Counseling Self-Estimate Inventory. J Couns Psychol. 1992;39(1):105-20. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.39.1.105

- 22. Hong SH, Choi HR. Contribution of counselor self-efficacy and state-anxiety to the working alliance in the early stage of counseling. Korean J Couns Psychother. 2001;13(1):31-49.

- 23. Park HJ, Lee KJ, Kim SS. A comparative study on the counseling self-efficacy and empathy of psychiatric nurses and general ward nurses. Health Nurs. 2014;26(1):9-19.

- 24. Lim SL. Marital communication and marital satisfaction: the effect of gender, demanding status difference, and personality [master's thesis]. Seoul: Korea University; 1998.

- 25. Kim EJ. Emergency nurse-patient interaction behavior. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2005;35(6):1004-13. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2005.35.6.1004

- 26. Lee HJ, Park BM, Shin MJ, Kim DY. Therapeutic communication experiences of nurses caring for patients with hematology. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(12):2403. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10122403

- 27. Jeon SS, Byun EK, Kim MY. Human understanding and communication. Paju: Soomoonsa; 2020.

- 28. Feldenzer K, Rosenzweig M, Soodalter JA, Schenker Y. Nurses' perspectives on the personal and professional impact of providing nurse-led primary palliative care in outpatient oncology settings. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2019;25(1):30-7. https://doi.org/10.12968/ijpn.2019.25.1.30

- 29. Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update: a U.S. Public Health Service report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):158-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009

- 30. Oh H. Effects of simulation learning using SBAR on clinical judgment and communication skills in undergraduate nursing students. Int J Contents. 2021;17(3):30-7. https://doi.org/10.5392/IJoC.2021.17.3.030

- 31. Kerr D, Martin P, Furber L, Winterburn S, Milnes S, Nielsen A, et al. Communication skills training for nurses: is it time for a standardised nursing model? Patient Educ Couns. 2022;105(7):1970-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2022.03.008

- 32. Kim EJ, Kang HY. The development and effects of a tailored simulation learning program for new nursing staffs in intensive care units and emergency rooms. J Korean Acad Soc Nurs Educ. 2015;21(1):95-107. https://doi.org/10.5977/jkasne.2015.21.1.95

- 33. Park BM. Effects of nurse-led intervention programs based on goal attainment theory: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9(6):699. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060699

- 34. Kusakli BY, Sonmez B. The effect of problem-solving and decision-making education on problem-solving and decision-making skills of nurse managers: a randomized controlled trial. Nurse Educ Pract. 2024;79:104063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2024.104063

- 35. Mahmoud S, Hassan M. Effectiveness of communication skills training program on empathetic skill and communication self efficacy of pediatric oncology nurses. IOSR J Nurs Health Sci. 2018;7(2):75-85.