Abstract

-

Purpose

The subjective experiences of middle-aged individuals during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic play a pivotal role in fostering resilience for reintegration into normal life post-pandemic and preparing for potential future infectious disease outbreaks. This study aimed to explore the experiences of middle-aged individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic using the Q methodology.

-

Methods

Forty-six middle-aged individuals from 10 cities in South Korea participated in this study. The participants arranged and ranked 39 Q statements describing their experiences with the COVID-19 pandemic using a Q-sort table. Subsequently, the data were analyzed using the PQ method.

-

Results

Three distinct viewpoints were identified: concerns regarding government policies related to COVID-19 (political perspective: consistent government policies are of utmost importance); concerns about personal loss related to COVID-19 (personal perspective: daily life is of the utmost importance); and concerns about social losses related to COVID-19 (social perspective: societal interests take precedence over individual needs).

-

Conclusion

The nursing interventions recommended for these three factors serve as a strategic blueprint for effectively addressing future outbreaks of infectious diseases. These nursing intervention strategies can significantly enhance positive perceptions of the three identified elements of the COVID-19 experience, providing an opportunity to transform negative outlooks into positive ones.

-

Key Words: COVID-19; Middle aged; Pandemics

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), originating in Wuhan, China, at the end of 2019, spread globally over the past few years (2020–2022), resulting in unprecedented loss of life, widespread lockdowns, and significant social and economic impacts [

1,

2]. COVID-19 has substantially affected the physical and mental well-being of individuals across all age groups, disrupting their daily routines [

3,

4]. As of September 3, 2023, South Korea documented 34,436,586 confirmed COVID-19 cases and 35,812 deaths [

5]. Despite the World Health Organization (WHO) announcing the end of the emergency phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in May 2023 and administering more than 13 billion vaccine doses globally by June 2023 [

6], the global situation remains concerning. Furthermore, conditions continue to evolve in South Korea despite fewer official updates regarding COVID-19 [

1,

7].

In South Korea, following WHO guidelines for the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing measures shifted most activities from outdoor to indoor settings [

7]. Vulnerable populations, such as children and the elderly, underwent self-quarantine to protect themselves from the virus [

8]. The transition from outdoor to indoor activities led to significantly increased economic and social responsibilities among middle-aged individuals, who are central to family caregiving [

9]. Additional burdens such as acquiring hand sanitizers and masks, adhering to vaccination protocols, and supporting children’s online learning have heightened financial and physical stress, negatively impacting the quality of midlife [

10]. Social distancing-induced depression and anxiety have had detrimental effects on the mental well-being of middle-aged individuals [

9,

11]. Additionally, concerns about COVID-19 vaccination side effects, increased disposable waste from food deliveries, and environmental pollution due to the increased use of disposable medical supplies have drawn attention [

3,

12,

13].

Middle age (40–64 years) is recognized as a transitional period bridging early adulthood and old age, linking younger and older generations. With rising life expectancy and increased socioeconomic and political engagement, middle-aged individuals play a critical role in family and societal functions [

14,

15]. Middle-aged individuals provide opportunities for their children’s healthy societal integration through family support, foster social order through active socioeconomic and political participation, and model societal behavior. Consequently, social expectations and responsibilities placed upon the middle-aged generation are inherently high [

9,

10]. Thus, middle-aged individuals’ thoughts, attitudes, and experiences regarding social issues significantly influence the broader socioeconomic and political landscape, yielding either positive or negative outcomes [

10,

11,

14,

15].

As of February 2024, South Korea’s population stood at 51,751,065 individuals, of whom 20,769,287 were classified as middle-aged, accounting for approximately 40.1% of the total population. The mean age of individuals in this middle-aged group was 46.1 years, expected to increase to 58.1 years by 2050 [

16]. Over the recent 3 years, following the emergence of COVID-19, middle-aged individuals have assumed pivotal roles in managing health issues within families, educational settings, and social circles, positively influencing child and family health management and adherence to community quarantine measures [

15]. Particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, the subjective experiences—such as decision-making, attitudes, and habits related to infection prevention—of middle-aged individuals significantly impact families, society, and the nation overall [

11,

14,

15]. Therefore, understanding the subjective experiences of middle-aged people during this period is crucial for fostering resilience and preparing effectively for future infectious disease outbreaks. However, there is a notable lack of data addressing this issue. Specifically, middle-aged parents' adherence to governmental infection control policies during the COVID-19 pandemic significantly affects their children and older parents, positively or negatively [

8-

10]. Furthermore, middle-aged parents’ economic capacity and social roles might influence their compliance with these policies [

15,

16]. Thus, investigating the experiences of middle-aged individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic will assist the government and citizens in reflecting on the crisis and provide essential data for managing future infectious diseases.

Human subjectivity, which comprises individuals’ interests, experiences, opinions, and thoughts influencing their behavior, is a critical research area in nursing due to its substantial role in modifying human attitudes and behaviors [

17]. Q methodology quantitatively represents individuals’ qualitative perspectives on specific topics, phenomena, or events [

18]. Subjectivity—encompassing personal thoughts, opinions, and perspectives—is foundational in nursing as it shapes holistic care and provides insights crucial for developing nursing education, research, and policy strategies. Thus, Q methodology serves as an optimal research tool for identifying and implementing nursing interventions by quantifying middle-aged individuals’ perspectives on their COVID-19 pandemic experiences. Additionally, middle-aged individuals’ vivid experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic provide essential insights into educational strategies for future infectious disease prevention and management, nursing research related to infectious disease response, and policy considerations for training nurses specializing in infectious disease care.

Various domestic and international quantitative and qualitative studies on the COVID-19 pandemic have focused on middle-aged individuals, examining factors such as coping strategies [

8], complementary and alternative therapies for stress reduction [

9], psychosocial and behavioral influences [

10,

11], and vaccination [

13]. However, few studies have employed Q methodology, which quantitatively assesses an individual's subjective experiences by integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches. The Q methodology uniquely captures middle-aged individuals’ subjective experiences, thoughts, and attitudes related to the COVID-19 pandemic, categorizing perspectives based on similarities among participants and providing tailored interventions for each identified group. Furthermore, the subjectivity of middle-aged individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic can reflect broader societal trends in managing and overcoming infectious diseases. This approach facilitates profound analyses of human experiences often absent in traditional quantitative studies.

This study aimed to uncover middle-aged individuals’ subjective experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic and explore tailored nursing interventions for each identified perspective. Customized nursing strategies for middle-aged individuals using Q methodology can significantly influence nursing practice, forming the basis for training nurses specializing in middle-aged care and enabling the development and implementation of targeted nursing education programs for this demographic.

METHODS

1. Study Design: Overview of Q Methodology

Introduced in 1935 by physicist-psychologist William Stephenson, Q methodology offers a comprehensive research approach that integrates qualitative and quantitative methods for the objective study of subjectivity. It aims to systematically explore individuals’ operant subjectivity, including their ideas, attitudes, viewpoints, and perspectives on specific topics [

19]. Q facilitates the identification of individuals’ perceptions and viewpoints, capturing consensus or divergence on particular issues. Q methodology is particularly prevalent in medical and nursing research [

17], playing a critical role in developing tailored intervention strategies by examining individuals’ thoughts and reactions to health challenges such as COVID-19 or specific illnesses. Within nursing education, Q methodology is an effective and streamlined research tool to investigate the attitudes, experiences, and perceptions of individual students or student groups [

17,

20]. Its flexibility in capturing participants’ subjectivity makes it suitable for educational research intended for broader populations [

19].

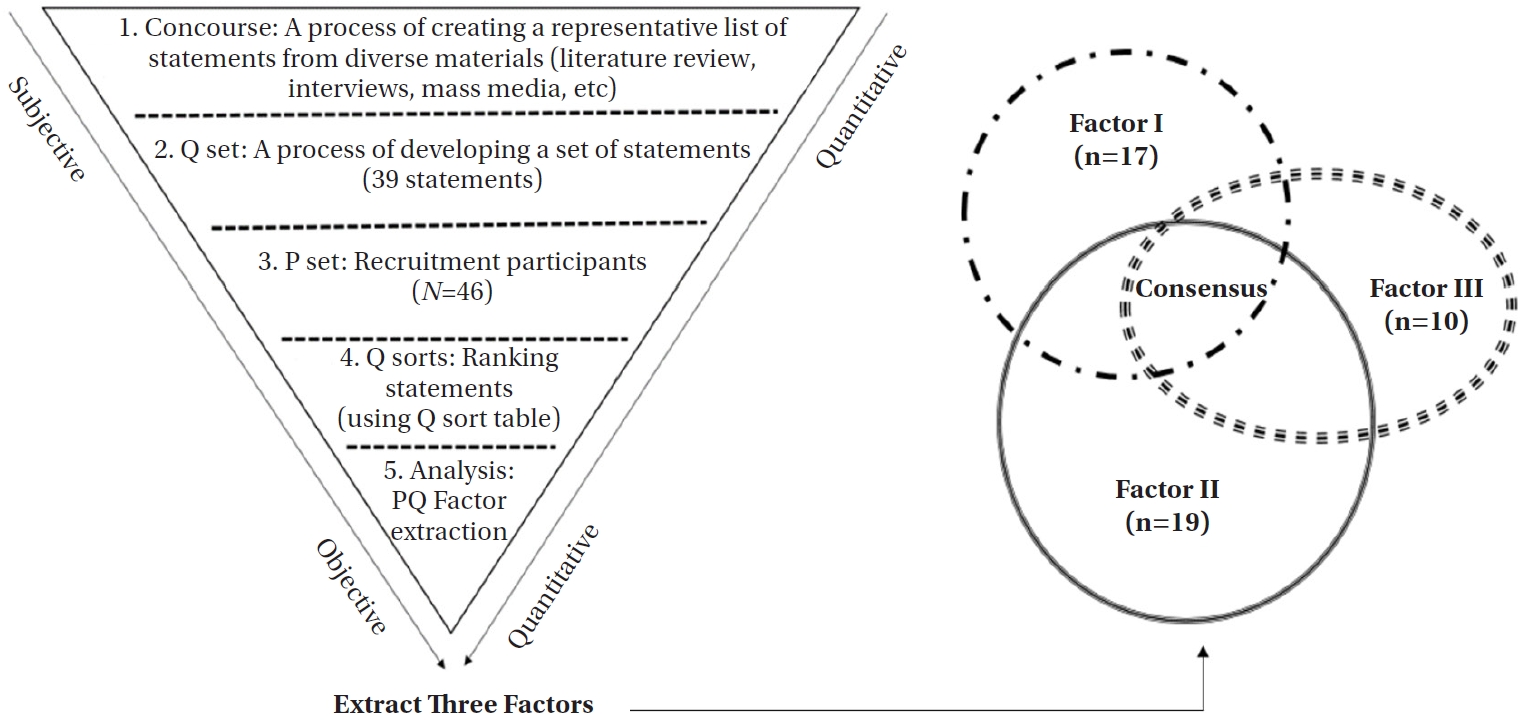

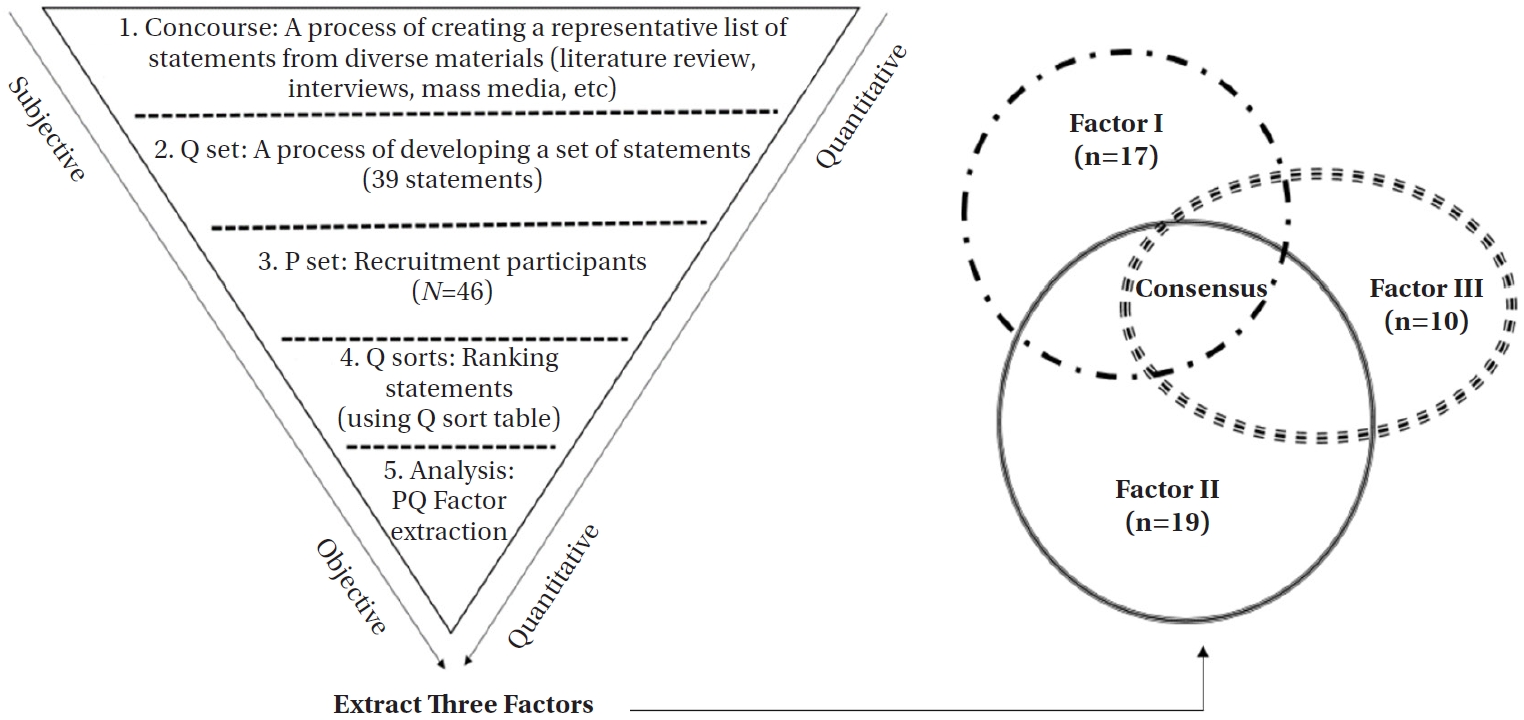

The Q methodology unfolds across five distinct steps, as illustrated in

Figure 1. The inclusion criteria for the study were as follows: married adults of any gender, aged between 40 and 64, holding Korean citizenship and residing in community settings; individuals or their family members who have experienced COVID-19 infection; participants capable of reading and writing; individuals without visual or auditory impairments; and individuals free from cognitive deficits and capable of organizing Q cards. Individuals not meeting these criteria were excluded from the study.

1) Concourse (process of creating a representative list of statements)

The initial phase of Q methodology, constructing a concourse of statements, is foundational. This stage involves generating a comprehensive pool of opinion statements from diverse sources such as literature reviews, individual or focus group interviews (FGIs), social media, newspapers, and periodicals [

17]. These materials aggregate the viewpoints and arguments of experts, groups, or organizations on contemporary issues or specific topics, such as COVID-19. Initially, the research team conducted an extensive review of scholarly journals, mass media coverage, and expert commentary on COVID-19. Additionally, opinions related to COVID-19 were collected from authoritative sources including the WHO, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Subsequently, FGIs were conducted with 25 middle-aged participants (five groups of five individuals each; age range: 42–55 years; gender distribution: 8 men and 17 women; employment status: six employed men and seven employed women; living arrangements: participants from five different areas living with family; all 25 participants had experienced COVID-19 infection). A snowball sampling method was utilized to deeply explore participants’ subjective experiences of COVID-19. The research team interviewed the 25 participants using semi-structured questions developed during the review phase. Before conducting the FGIs, a pilot test was performed with two volunteers to ensure clarity and comprehensibility of the semi-structured questions and terminology used. The interviews took place in calm and welcoming settings (study café and researcher’s office) to foster open and honest discussions of participants’ experiences and perceptions. All interviews were audio-recorded with prior consent, and participants were informed that recordings would be deleted upon study completion. Additionally, some participants reviewed their transcripts personally to confirm accuracy. The semi-structured interview questions included the following: (1) Identifying the most challenging aspect of the COVID-19 pandemic; (2) Discerning any unexpected positive outcomes from the COVID-19 pandemic; (3) Sharing insights and personal experiences regarding preventive measures endorsed by the government to mitigate COVID-19 transmission, including hand hygiene and social distancing; (4) Reflecting on the involvement of healthcare professionals in managing the COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting any regrets or commendations; (5) Evaluating the government’s response to COVID-19, including any aspects of regret or commendation; (6) Providing opinions on COVID-19 vaccination and, for those vaccinated, sharing experiences; (7) Offering any additional experiences related to COVID-19.

Based on data collected through the extensive literature review and FGIs, the researcher and eight research assistants undertook a process to eliminate duplicate or irrelevant statements, resulting in 134 initial statements. Typically, deriving a final set of statements from the initial pool is conducted by a panel of experts in Q methodology [

17]. Accordingly, a panel comprising a Q methodologist, two nursing professors, and two hospital-based nurses, all experienced in Q methodology research, was assembled to evaluate the clarity and conciseness of the 134 statements. This panel reviewed the statements, eliminating or revising those deemed ambiguous or redundant. This selection process, characterized by collaboration between researchers and expert panels, involves gradually reducing the number of statements through careful assessment of redundancy and ambiguity [

19]. Given that this iterative process is repeated multiple times to derive the final Q-set, meticulous selection of statements is crucial. In this study, each statement was scored on a scale ranging from 1 to 4 points. Statements receiving scores of 1 to 2 (indicating irrelevance or redundancy) were eliminated, while those scoring 3 to 4 were modified and refined to align with the research objectives. This iterative selection process was conducted seven times, resulting in a final set of 68 statements.

2) Q-set (process of developing a set of statements)

The second phase in Q methodology involves refining the previously broad concourse by removing ambiguous or redundant statements, thus establishing a precise and clear final set of statements known as the Q-set. The number of statements in a Q-set typically ranges from 20 to 100, and while the optimal quantity remains debated [

17], achieving a balance is key. A larger statement set prolongs the Q-sorting process, which must be considered during the development of the Q-set. Brown [

19] recommended an ideal Q-set size of approximately 40 to 50 statements; however, Hensel et al. [

20], in their “A scoping review of Q methodology in nursing education studies,” indicated that the number of stimuli for Q-sorting varied between 21 and 60 statements. Reflecting on these recommendations, a panel of five experts reviewed the initial 68 statements for redundancy and ambiguity, ultimately developing the final Q-set, consisting of 39 statements (

Table 1). To verify the effectiveness of the Q-set, a pilot evaluation was conducted with six middle-aged volunteers (age range: 42–55 years; sex: 2 men, 4 women; employment status: 2 employed men, 3 employed women; living arrangements: residing with family in five different areas; all six individuals had experienced COVID-19 infection) before advancing to subsequent phases. Results from the pilot test confirmed that the 39 statements were clear, readable, and free from ambiguity or redundancy.

3) P-set (process of recruiting study participants)

The third phase, known as the P-set phase, involves recruiting a group of participants tasked with categorizing the Q-set statements. This participant group, referred to as the P (person)-set or P-sample, is traditionally established following the principle of utilizing small sample sizes [

17,

19]. The focus in Q methodology is not on the number of participants, but rather on capturing individual perspectives regarding a specific issue. According to Brown [

19], a sample of 40 to 60 participants is generally sufficient for most studies, although fewer participants may suffice for certain research contexts. In this study, a convenience sample of 46 middle-aged married individuals (both men and women) residing in Seoul Metropolitan City and other regions throughout South Korea was recruited. Data collection took place from March 15, 2022, to July 30, 2022. To achieve an even distribution of participants across various regions, research assistants from eight different locations collected data.

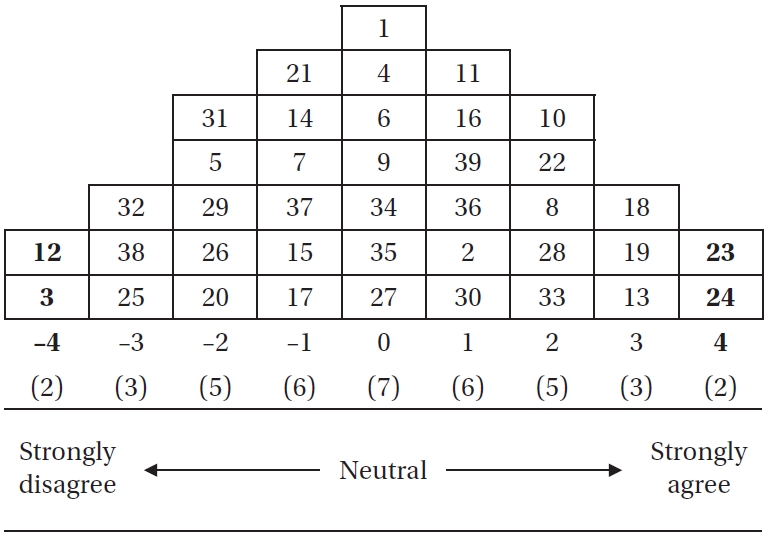

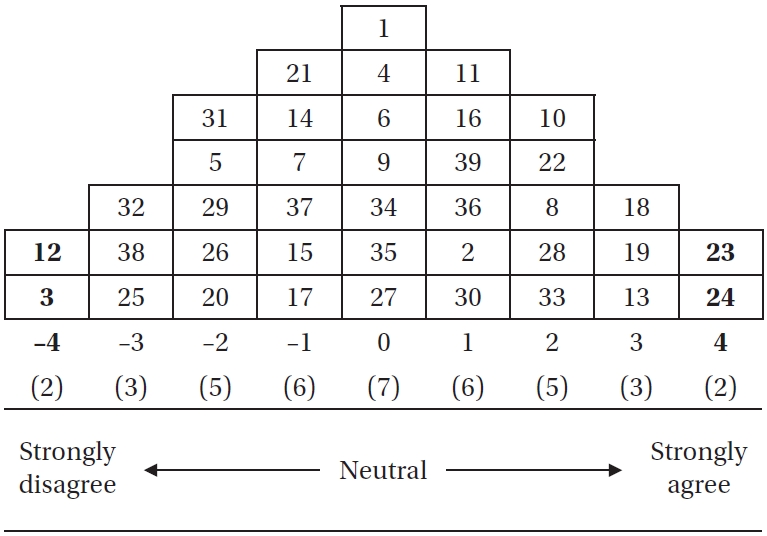

4) Q-sort (process of ranking a Q-set)

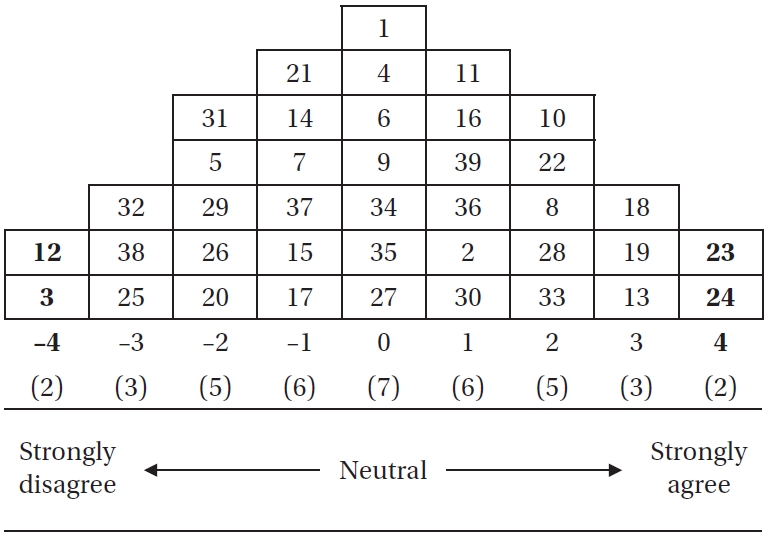

The fourth phase of Q methodology involves participants systematically ranking the Q-set statements, which are printed on small cards and placed at specific positions on a grid known as a Q-sort table. Numerical rankings on the Q-sort table typically range from –4 to +4, where –4 indicates the most disagreeable or strongly negative position, 0 represents neutrality, and +4 indicates the most agreeable or strongly positive position. During the Q-sorting process, participants arrange statements according to a predefined quasi-normal distribution, thereby minimizing researcher bias and maximizing the authentic representation of participants’ perspectives. An example of a completed Q-sort from this study is illustrated in

Figure 2. Following the Q-sorting activity, the research team asked all 46 participants to provide post-sorting narratives explaining their reasons for placing certain statements at the extreme ends (+4 and –4 positions) of the Q-sort table. These post-sorting narratives, conducted through brief interviews or written statements, are strongly recommended in Q methodology to further understand the rationale behind participants’ extreme rankings. This supplementary qualitative information not only enriches the descriptions but also aids in comprehending the distinctive characteristics of each factor identified through factor analysis.

5) Factor extraction and interpretation (process of analyzing collected data)

The fifth phase of Q methodology entails analyzing the collected data using a variant of the PQ method, which is specifically optimized for Q studies. The PQ method employs diverse statistical techniques that allow researchers to input statement rankings (Q-sorts) into the Q-sort table, subsequently calculating correlations between the Q-sorts. Factor analysis is then conducted using either centroid factor analysis or principal component analysis methods [

17]. This analytical process produces multiple outputs, including tables displaying factor loadings, standardized factor scores (z-scores: greater than +1.0 indicating strong agreement; less than –1.0 indicating strong disagreement), statements distinguishing differences among identified factors, and consensus statements across factors.

Before commencing the study, ethical approval (1044297-HR-202109-005-02) was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Jungwon University. Participants were assured of the anonymity and confidentiality of their participation. They were informed that they could withdraw from the study at any time and that the collected data would be securely stored in the research laboratory’s archives, exclusively for research purposes. After clearly explaining the study’s objectives and emphasizing voluntary participation, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

4. Rigor

To ensure the credibility and rigor of the Q methodology study, all research procedures and analyses strictly adhered to Brown’s methodological principles and technical approaches [

19]. Each step of the research process was validated using the reporting guidelines outlined by Churruca and the Assessment and Review Instrument for Q-methodology (ARIQ) checklist developed by Dziopa, ensuring rigorous adherence to established protocols [

18,

21]. Furthermore, the FGIs conducted during the concourse construction phase (Step 1) followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ), which includes a comprehensive 32-item checklist [

22]. Similar to procedures employed in quantitative research, incorporating mixed methods within Q methodology enhances the study's validity and reliability. The validity of our Q study was underpinned by content and face validity evaluations and reinforced through the Q-sorting process. Content and face validity were evaluated by five expert reviewers, and Q-sorting data were collected from six middle-aged individuals of both genders, recruited via convenience sampling. Reliability was assured through the test-retest method, involving administering the same Q-sample to identical participants at two different time intervals, with an expected correlation coefficient of .80 or higher [

17,

19]. To confirm the study’s reliability, a convenience sample of six middle-aged participants of both sexes underwent a test-retest procedure at two-week intervals, resulting in correlation coefficients ranging from 0.83 to 0.88 for each Q-sort.

RESULTS

Three distinct factors emerged from the 39 statements describing the COVID-19 pandemic experiences of middle-aged men and women (

Figure 1).

Table 1 illustrates the positioning of these 39 statements on the Q-sort grid for each of the three factors. An asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant differences (

p<.01) in statement scores compared to the other factors. Statements presented in bold represent common viewpoints that were either positively or negatively agreed upon across all three factors. Identifying both distinct and common statements helps clarify differences and shared opinions among the identified factors. The eigenvalues of these three factors were 9.81, 7.17, and 2.72, respectively. Factor I accounted for 21.3% of the variance, factor II for 9.5%, and factor III for 5.9%, with a cumulative variance percentage of 36.7% for these three factors. Notably, the eigenvalue and variance percentage of factor I were conspicuously higher than those of factors II and III. Therefore, factor I explained the COVID-19 pandemic experiences among middle-aged individuals more effectively than the other two factors. The correlation coefficients among the three factors were as follows: r=–.08 between factors I and II, r=.49 between factors I and III, and r=–.28 between factors II and III (

Table 2).

Out of the 46 participants, 17 (37.0%) were classified under factor I. Among these, nine (52.9%) were female, with an equal distribution between those in their 40s and those in their 50s. Furthermore, 11 participants (64.7%) reported having no religious affiliation. Educationally, 11 (64.7%) had college degrees or higher; 10 (57.8%) resided in metropolitan cities; 12 (70.6%) were employed; and nine (52.9%) described their financial status as average. Economic losses due to COVID-19 were reported by nine (52.9%) participants, while seven (41.2%) rated their health as good and eight (47.1%) as average. Notably, 15 participants (88.2%) had school-aged children. Ten participants (58.8%) indicated low levels of COVID-19 knowledge, 11 (64.7%) had undergone COVID-19 testing, 15 (88.2%) were vaccinated against COVID-19, and 11 (64.7%) rated the COVID-19 quarantine rules as average (

Table 2).

Participants associated with factor I strongly agreed (+4, positive perspective) with statements Q23 (importance of strict personal hygiene) and Q24 (expressing gratitude toward medical staff), compared to participants in factors II and III. The most significant disagreements (–4, negative perspective) were with statements Q1 (disruption of daily routines) and Q4 (estranged relationships with parents) (

Table 1). Representative remarks illustrating this factor included:

Rather than offering free COVID-19 testing and vaccinations, it would have been more fiscally responsible to differentiate access based on economic status. (Participant 4)

The government's COVID-19 policy has been inconsistent and often confusing, as it has changed daily. In particular, the guidelines regarding vaccination, social distancing, and online learning have lacked clarity. (Participant 5)

Table 3 further illustrates the characteristics of factor I through post-sorting narratives, detailing participants’ reasons for placing statements at the extreme ends (+4 and –4) of the grid. These perspectives reflect concerns primarily centered on government policies related to COVID-19.

2. Factor II: Concerns about Personal Loss Related to COVID-19 (Personal Perspectives)

Nineteen of the 46 participants (41.3%) were categorized under factor II. This group included 10 women (52.6%), with the majority, 13 participants (68.4%), aged between 51 and 60 years, and 12 (63.2%) reporting no religious affiliation. Educationally, 10 participants (52.6%) had completed high school. Twelve (63.2%) resided in metropolitan cities, and 14 (73.7%) were employed. Thirteen participants (68.4%) described their financial status as average, and an equal number reported experiencing economic losses due to COVID-19. Health was described as average by 11 participants (57.9%), and 13 (68.4%) had school-aged children. Low COVID-19 knowledge was indicated by 14 participants (73.7%); 13 (68.4%) had undergone COVID-19 testing, and 17 (89.5%) had received the COVID-19 vaccination. The effectiveness of quarantine rules was perceived as average by 11 (57.9%) (

Table 2).

Participants associated with factor II strongly agreed (+4, positive perspective) with statements Q19 (realizing the importance of life before COVID-19) and Q24 (gratitude toward medical staff) compared to factors I and III. The strongest disagreements (–4, negative perspective) were with statements Q17 (preferring to work from home) and Q29 (satisfaction with government COVID-19 policies) (

Table 1). Representative remarks illustrating this factor included:

First and foremost, I am deeply frustrated by how COVID-19 has disrupted my personal life. I also feel a sense of self-loathing for my tendency to avoid social interactions. (Participant 20)

While I recognize the importance of government policies, I am increasingly concerned about my future, given the current economic challenges. (Participant 41)

Table 3 provides additional insights into factor II through participants’ post-sorting narratives, explaining their reasoning for extreme statement placements (+4 and –4). These narratives reflect significant concerns regarding personal losses due to COVID-19.

3. Factor III: Concerns about Social Losses Related to COVID-19 (Social Perspectives)

Ten participants (21.7%) aligned with factor III. This group comprised seven women (70.0%), evenly distributed between those in their 40s and 50s. Six participants (60.0%) reported no religious affiliation, and seven (70.0%) indicated high school graduation as their highest education level. Eight participants (80.0%) lived in metropolitan cities, seven (70.0%) were employed, and half described their financial status as average. Economic impacts due to COVID-19 were reported by five participants (50.0%), and six (60.0%) described their health as average. All 10 participants had school-aged children; eight (80.0%) indicated low knowledge about COVID-19, six (60.0%) had undergone COVID-19 testing, all were vaccinated, and seven (70.0%) viewed the quarantine rules as average (

Table 2).

Participants associated with factor III strongly agreed (+4, positive perspective) with statements Q13 (disappointment regarding online classes) and Q19 (realizing life’s importance before COVID-19) compared to participants in factors I and II. The strongest disagreements (–4, negative perspective) were with statements Q17 (preference for working from home) and Q25 (regrets regarding medical institutions) (

Table 1). Representative remarks illustrating this factor included:

As we navigate the COVID-19 pandemic, I am increasingly concerned about the environmental pollution resulting from disposable waste and medical waste, particularly masks. While I can accept the limitations on visiting my parents and the restrictions on gatherings due to social distancing, I am deeply troubled by the prospect of leaving a polluted future for my children. (Participant 11)

I wish people would prioritize social benefits over personal inconveniences. I hope they will adhere to government policies, such as social distancing and vaccinations, to prevent the spread of infection. It is essential for society to remain orderly. (Participant 30)

Parents and society should take the initiative to ensure that students can effectively engage in online education. The future of education should not be compromised due to the impact of COVID-19. (Participant 46)

Table 3 further illustrates the characteristics of factor III through post-sorting narratives, highlighting participants’ reasons for placing statements at extreme positions (+4 and –4). This factor emphasizes prioritizing public and societal interests over personal inconvenience during the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Consensus Statements between the Three Factors

Several statements revealed areas of agreement or disagreement shared among all three factors (see bold statements in

Table 1). Specifically, all three factors collectively agreed with statement 7 (“Living while wearing a mask was inconvenient”) and statement 24 (“Appreciation for the hard work of medical staff”). Conversely, all three factors disagreed with statements 3 (“Isolation due to social distancing”), 4 (“Relationship with parents strained due to social distancing”), and 5 (“Decreased personal time”). In other words, the three factors showed positive consensus regarding adherence to infection control guidelines during the COVID-19 pandemic and expressed gratitude toward medical personnel for their dedication. On the other hand, all respondents conveyed negative sentiments about inconveniences resulting from social distancing measures.

DISCUSSION

1. Factor I: Concerns about Government Policies Related to COVID-19 (Political Perspectives)

The distinguishing characteristic of factor I is its emphasis on concerns regarding government policies related to COVID-19. Members of this group highlighted the importance of government interventions such as diverse monitoring systems, quarantine measures, and social distancing protocols. Furthermore, this group prioritizes government policies over individual convenience, believing their daily routines have not been significantly disrupted and their relationships with family members have remained intact despite the pandemic (see Q1 and Q4 in

Table 1). However, they expressed criticism of the government’s inconsistent and chaotic approach to COVID-19 policies. Specifically, they appreciated the dedication of medical staff in treating COVID-19 (refer to Q24 in

Table 1) but criticized hospitals for unclear strategies regarding patient treatment (refer to factor 1 in

Table 3). Although participants recognized the importance of COVID-19 vaccination, their trust was diminished by unclear guidelines related to vaccination procedures and potential side effects (see Q38 and Q39 in

Table 1).

These findings align with a study by El-Elimat et al. [

13], which investigated attitudes toward the COVID-19 vaccine among 3,100 Jordanians and revealed a low acceptance rate (37.4%) along with prevalent conspiracy theories. Similarly, a survey of 15,087 Libyans conducted by Elhadi et al. [

23] found that while 79.6% (12,066 participants) viewed the COVID-19 vaccine positively, 37% (5,579 participants) had concerns about severe side effects. Elhadi et al. [

23] also noted that vaccine skepticism could lead to hesitancy and delay in vaccination, potentially causing widespread infections. Conversely, AlShurman et al. [

12] reported that strong trust, social cohesion, and political belief in governmental COVID-19 measures were associated with greater vaccine acceptance and reduced anxiety regarding vaccine side effects.

Unlike factors II and III, factor I was characterized by participants with higher education levels but limited knowledge about COVID-19. Generally, individuals with less knowledge about COVID-19 tend to exhibit more negative attitudes toward government policies and vaccinations [

24]. Conversely, increased knowledge and awareness of COVID-19 correlate positively with adherence to preventive measures [

25]. Therefore, before mandating COVID-19 vaccinations, the government’s provision of clear and comprehensive vaccine information and management of side effects could positively impact vaccine acceptance among individuals in factor I. Middle age represents a critical life phase characterized by significant responsibilities such as child-rearing, elder care, and family financial security. Positive perceptions and attitudes toward COVID-19 policies and vaccines among middle-aged individuals can potentially influence overall compliance and effectiveness of government policies. Opening easily accessible online communication channels, broadcasting media, and utilizing social networking services to provide real-time updates on governmental infectious disease policies and information can serve as effective strategies for supporting middle-aged individuals in family care. Additionally, establishing a specialized nursing counseling system tailored specifically for middle-aged people could further enhance the successful implementation of these policies.

Factor II is primarily characterized by concerns regarding the detrimental impact of COVID-19 on personal lives and the notable decline among independent small-business owners. Similar to factor I, participants in factor II were dissatisfied with government management of the COVID-19 pandemic; however, their criticisms focused mainly on negative economic consequences for individuals and self-employed persons (refer to Q9 and Q11 in

Table 1), stemming from the government’s inconsistent enforcement of COVID-19 measures. A unique characteristic of this group, unlike factors I and III, is their preference for avoiding social interactions to reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission, as reflected in Q2 and Q22 of

Table 1. Furthermore, factor II expressed stronger opposition toward compulsory government-mandated COVID-19 vaccinations than the other groups (refer to Q36 in

Table 1). Factor II included a substantial proportion of participants aged 50 to 64 years (73.7%), a demographic that experienced particularly harsh economic repercussions due to COVID-19, leading to the emergence of sociocultural values prioritizing individual well-being and interests over collective considerations.

As of June 2021, during the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea, the number of self-employed individuals without employees increased by 113,000, and 761,000 businesses had shut down—93.8% of which involved self-employed individuals [

26]. By February 2024, although the numbers of self-employed without employees and related business closures had declined, the long-term economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic persisted.

Shon and Moon [

27] observed that the economic burden resulting from COVID-19 was primarily borne by self-employed, freelance, and low-income workers. Kim et al. [

25], in their study on the impact of COVID-19 on the self-employed and government policies, similarly demonstrated that self-employed individuals experienced the most significant economic difficulties, especially within micro-enterprises. Research by Koyama et al. [

28], involving 27,575 participants in Osaka, Japan, indicated that individuals experiencing economic hardship due to COVID-19 were more likely to postpone or avoid necessary dental care compared to their financially stable counterparts. Lee et al. [

29] also identified a strong correlation between economic downturns due to COVID-19 and increased risk of depression. Therefore, tailored economic support addressing the financial volatility and challenges experienced by micro-enterprises during the COVID-19 crisis could positively influence factor II’s perspectives. Additionally, factor II represents individuals of lower economic status who experienced financial losses and disruption to personal lives due to COVID-19, coupled with a limited understanding of the virus (refer to Q1 in

Table 1,

Table 2, and factor II in

Table 3). The psychological stress and economic hardships caused by the COVID-19 pandemic can negatively impact physical health and psychosocial behaviors among middle-aged individuals [

10,

28]. Although universal support measures, such as emergency disaster relief funds, are beneficial, a comprehensive support framework addressing physical, mental, social, and economic aspects is essential for effectively assisting individuals categorized under factor II. Implementing specialized counseling and support centers specifically for self-employed individuals, as well as establishing counseling nurse programs focused on stress relief, represent effective strategies to address the concerns and challenges identified in factor II.

The most distinctive attribute of factor III is its broadly positive and cooperative stance toward government policies related to COVID-19, including quarantine measures and vaccination guidelines. Individuals in this group prioritize societal interests over personal ones and express particular concerns regarding significant environmental pollution resulting from disposable products used during the pandemic (see Q10, 25, 33, 36, 37, 38, and 39 in

Table 1). They also exhibit apprehension about the closure of schools and the subsequent decline in educational quality due to the transition to online classes (see Q13). Notably, factor III, unlike other demographic groups, includes a substantial proportion of individuals in their 40s and 50s (70%). All of these individuals have school-aged children, leading them to emphasize the importance of maintaining a healthy environment, education system, and society for the future of their children rather than for their own immediate benefit.

A study by Islam et al. [

24], involving 392 participants from Bangladesh exploring their experiences with the COVID-19 vaccine, found that despite 63.6% reporting side effects, 85.5% were satisfied with the vaccine administration process. Additionally, 88.0% supported vaccination as a means to rapidly achieve community-wide herd immunity, emphasizing that vaccination plays a crucial role in mitigating the impacts of COVID-19. Allington et al. [

30], who surveyed 4,343 individuals in the United Kingdom regarding their views on COVID-19 vaccination, identified a positive correlation between decreased trust in government institutions and increased vaccine hesitancy. In contrast, Carrieri et al. [

31] surveyed over 35,000 Europeans and found that greater confidence in government COVID-19 measures and scientific guidelines correlated with more favorable views toward COVID-19 vaccination, consequently reducing vaccine hesitancy. Providing accurate and timely information about governmental COVID-19 policies and vaccination through various media platforms is therefore crucial for individuals aligned with factor III. Specifically, establishing a text messaging system tailored for middle-aged individuals to disseminate vaccine information and organizing educational meetings on vaccination could be particularly beneficial.

Factor III’s strong orientation toward social welfare highlights significant concerns about the environmental damage caused by disposable products during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers Roy and Chaube [

3], along with Chakraborty et al. [

1], observed that increased mass testing and biohazardous waste generation could have long-lasting adverse effects on global environmental and public health. Hantoko et al. [

32] emphasized the necessity of developing short-term, mid-term, and long-term strategies to manage quarantine supplies, food, disposable plastics, and infectious waste effectively across homes, healthcare institutions, and quarantine centers. Iranmanesh et al. [

33], in their review of 38 studies, noted that most countries experienced a reduction in household food waste during the pandemic. Vasko et al. [

34], surveying 2,425 participants in Bosnia and Herzegovina, similarly observed decreased household food waste accompanied by the adoption of waste-minimizing behaviors during the pandemic. Conversely, Ikiz et al. [

35] reported a 75% increase in household food waste during the pandemic, underscoring the importance of educational programs and campaigns to enhance waste management and reduction.

Given the potential for future pandemics and global lockdown scenarios similar to COVID-19, it is critical for governments to develop sustainable environmental protection strategies. Communities should be encouraged to minimize food waste and reduce the use of single-use products, while healthcare facilities must adopt efficient methods to handle biohazardous waste generated by infectious diseases. Strengthening the volume-based waste fee system and initiating competitions to encourage the reuse of disposable items could be particularly advantageous.

4. Strengths and Limitations

Q methodology provides a distinct advantage in terms of cost-effective research, as it typically requires only a single subject per session and a limited number of research participants overall. The primary strength of this study is its ability to systematically categorize the personal perspectives of middle-aged individuals—who bear significant responsibility for family health and caregiving—into distinct factors, and subsequently recommend specific nursing strategies tailored to each factor. However, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, because Q methodology emphasizes the exploration of subjective individual perspectives, the number of study participants is of lesser importance, and employing larger samples might obscure the unique views of individuals. Nevertheless, the small convenience sample utilized in this study may limit the generalizability of the findings to a broader population of middle-aged individuals across various national and cultural contexts. Second, this study specifically investigated the experiences of middle-aged South Korean residents during the COVID-19 pandemic; therefore, variations in policies and responses to COVID-19 in other countries could potentially influence the transferability of these findings. Third, although participants were recruited from across South Korea, a balanced regional distribution of participants was not achieved due to restrictions related to social distancing measures. Consequently, caution should be exercised when generalizing the study's results. Fourth, although there is no absolute threshold established for cumulative variance in Q methodology, a cumulative variance of 25% to 30% or higher is generally considered meaningful in this field [

19]. In this study, the cumulative variance was 36.7%, indicating significant findings. Nonetheless, developing a diverse range of statements related to COVID-19 experiences proved challenging due to reliance on convenience sampling for participant interviews, potentially influencing the derivation of factors and the cumulative variance. Therefore, conducting a follow-up study after the complete resolution of the COVID-19 pandemic would likely capture a broader array of experiences not included in this study. To enhance the objectivity and reliability of future research examining middle-aged individuals’ experiences with COVID-19, it is recommended that probability sampling methods be used. Although probability sampling methods can be costly and time-consuming, they significantly enhance the representativeness of the sample, thereby increasing the reliability of findings in Q-methodological studies, which often face challenges related to generalizability. Given that COVID-19 has affected individuals across all age groups and not just middle-aged populations, follow-up studies that include adolescents and elderly populations could be particularly beneficial for developing life-cycle-specific nursing education programs focused on infectious disease prevention.

CONCLUSION

The analysis of the forced distribution of the 39 statements in the Q-sort table by 46 middle-aged participants identified three distinct factors representing experiences, thoughts, and attitudes of middle-aged South Koreans regarding the COVID-19 pandemic. These statements offer valuable insights for understanding government responses to infectious diseases, vaccine implementation strategies, societal changes resulting from COVID-19, and lifestyle adaptations during the pandemic in South Korea. Recommended nursing interventions for these three factors provide a strategic framework for effectively managing future infectious disease outbreaks. Based on the study's findings, it is crucial for government officials, societal stakeholders, and nursing policy developers to collaborate on designing and implementing diverse educational initiatives addressing infectious diseases such as COVID-19. Such initiatives can significantly foster positive perceptions regarding the three identified factors, ultimately transforming negative attitudes into positive ones. Most importantly, these findings offer nursing practitioners working in clinical settings, public health centers, and community-based services valuable insights into managing and responding to infectious diseases. Additionally, the study serves as a practical resource for developing and implementing targeted nursing interventions tailored specifically to the identified factors.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declared no conflict of interest.

-

FUNDING

None.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I am genuinely grateful to the middle-aged individuals who participated in this study for sharing their thoughts and viewpoints about the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data can be obtained from the corresponding authors.

Figure 1.The study procedure and its outcomes.

Figure 2.An example of 39 Q cards arrangement (participant 8). The number in parentheses indicates the number of cards.

Table 1.Factor Arrays (Item by Ranked Position) (N=46)

|

Q-Statements |

Ⅰ (n=17) |

Ⅱ (n=19) |

Ⅲ (n=10) |

|

1. My daily routine disintegrated. |

–4†

|

+2†

|

0 |

|

2. I was always anxious about contracting COVID-19. |

0 |

+3 |

+2 |

|

3. I felt isolated because of social distancing.

|

–3 |

–1 |

–3 |

|

4. My relationship with my parents has become distant due to social distancing.

|

–4 |

–2 |

–2 |

|

5. My time dwindled as my family spent more time at home.

|

–2 |

–3 |

–3 |

|

6. My health deteriorated due to a decrease in outdoor activity. |

–3 |

–1 |

–2 |

|

7. Living while wearing a mask was inconvenient.

|

+2 |

+3 |

+3 |

|

8. I was careful about avoiding infection from other people. |

–1 |

+2 |

+1 |

|

9. The household economy has become challenging due to the prolonged COVID-19 pandemic. |

–3†

|

+2†

|

0 |

|

10. Environmental pollution has become serious due to the increase in the use of single-use waste. |

–2†

|

+1 |

+3†

|

|

11. It was heartbreaking for the self-employed to be severely affected. |

0 |

+3†

|

0 |

|

12. Fake news related to COVID-19 has made me more anxious. |

–2 |

–1 |

–2 |

|

13. It was disappointing that the students could not attend high-quality classes due to remote learning. |

–1†

|

+2 |

+4†

|

|

14. It was nice to be able to skip family and work events. |

–2†

|

–1 |

+2†

|

|

15. As social activity decreased, expenditures also decreased. |

–1 |

–1 |

–1 |

|

16. Everyday life has changed to become family-centered. |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

17. Working from home freed me from commuting. |

–1 |

–4 |

–4†

|

|

18. The environment was rather hygienic due to frequent disinfection. |

+1 |

+1 |

0 |

|

19. I realized how precious life was before the COVID-19 pandemic. |

0 |

+4 |

+4 |

|

20. The increase in the use of food delivery, online shopping, and parcel delivery has made life more convenient. |

0 |

0 |

–2†

|

|

21. It was good not to care about appearance because of wearing a mask. |

+1 |

0 |

–2†

|

|

22. I started avoiding places where many people gather. |

+1 |

+2 |

+3 |

|

23. I became very strict about personal hygiene. |

+4 |

0 |

+1 |

|

24. Thank you for the sacrifice and dedication of the medical staff.

|

+4 |

+4 |

+2 |

|

25. The rigid response of medical institutions solely following government quarantine guidelines was disappointing. |

0 |

–2 |

–4 |

|

26. The government quarantine guidelines were overly formal and inconsistent with reality. |

+1 |

0 |

0 |

|

27. The Korean people have complied with the government's quarantine guidelines. |

+1 |

–1 |

–1 |

|

28. I was happy to receive the disaster aid. |

+2 |

–2†

|

+2 |

|

29. I am satisfied with the COVID-19 policy. |

–2 |

–4†

|

–1 |

|

30. A continuous infectious disease management system is necessary. |

+3 |

+1 |

+1 |

|

31. It was too cumbersome to write in a guestbook, scan the QR code, and check body temperature. |

+1 |

–2†

|

+2†

|

|

32 Accessing information related to COVID-19 was challenging due to a lack of familiarity with the Internet. |

–1 |

–2 |

–1 |

|

33. The government's official daily briefing on COVID-19 was very helpful. |

0 |

–3†

|

+1†

|

|

34. Strict punishment and regulations are necessary for non-compliance with quarantine rules. |

+2 |

+1 |

0 |

|

35. It was good that tests and vaccines for COVID-19 were provided free of charge. |

+2 |

0 |

+1 |

|

36. Vaccination is mandatory in the interest of public health. |

–1 |

–3†

|

+1†

|

|

37. The COVID-19 vaccination is a voluntary choice and not mandatory. |

+2†

|

0 |

–3†

|

|

38. There was significant anxiety about potential adverse reactions and side effects following COVID-19 vaccination. |

+3†

|

+1 |

–1†

|

|

39. There is a necessity for a comprehensive management system concerning adverse reactions, reporting, and compensation associated with the COVID-19 vaccination. |

+3†

|

+1 |

–1†

|

Table 2.Demographic Characteristics (N=46)

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

Factor Ⅰ (n=17) |

Factor Ⅱ (n=19) |

Factor Ⅲ (n=10) |

|

Eigenvalue (variance, %) |

9.81 (21.3) |

7.17 (9.5) |

2.72 (5.91) |

|

Cumulative (%) |

21.3 |

30.8 |

36.7 |

|

Sex |

Men |

8 (47.1) |

9 (47.4) |

3 (30.0) |

|

Women |

9 (52.9) |

10 (52.6) |

7 (70.0) |

|

Age (year) |

40–50 |

9 (52.9) |

5 (26.3) |

7 (70.0) |

|

51–60 |

8 (47.1) |

13 (68.4) |

3 (30.0) |

|

61–64 |

0 |

1 (5.3) |

0 |

|

Religion |

Yes |

6 (35.3) |

7 (36.8) |

4 (40.0) |

|

No |

11 (64.7) |

12 (63.2) |

6 (60.0) |

|

Education |

High school |

6 (35.3) |

10 (52.6) |

7 (70.0) |

|

College or higher |

11 (64.7) |

9 (47.4) |

3 (30.0) |

|

Residence |

Seoul |

3 (17.6) |

4 (21.1) |

1 (10.0) |

|

Metropolitan |

10 (58.8) |

12 (63.2) |

8 (80.0) |

|

Province |

4 (23.5) |

3 (15.8) |

1 (10.0) |

|

Job |

Employee |

12 (70.6) |

14 (73.7) |

7 (70.0) |

|

No job |

1 (5.9) |

2 (10.5) |

2 (20.2) |

|

Self employed |

4 (23.5) |

3 (15.8) |

1 (10.0) |

|

Financial status |

Good |

4 (23.5) |

0 |

2 (20.0) |

|

Average |

9 (52.9) |

13 (68.4) |

5 (50.0) |

|

Bad |

4 (23.5) |

6 (31.6) |

3 (30.0) |

|

Economic damage due to COVID-19 |

Yes |

9 (52.9) |

13 (68.4) |

5 (50.0) |

|

No |

8 (47.1) |

6 (31.6) |

5 (50.0) |

|

Health status |

Good |

7 (41.2) |

6 (31.6) |

4 (40.0) |

|

Average |

8 (47.1) |

11 (57.9) |

6 (60.0) |

|

Bad |

2 (11.8) |

2 (10.5) |

0 |

|

School children |

Yes |

15 (88.2) |

13 (68.4) |

10 (10.0) |

|

No |

2 (11.8) |

6 (31.6) |

0 |

|

Knowledge of COVID-19 |

Good |

7 (41.2) |

5 (26.3) |

2 (20.0) |

|

Bad |

10 (58.8) |

14 (73.7) |

8 (80.0) |

|

Experience in COVID-19 test |

Yes |

11 (64.7) |

13 (68.4) |

6 (60.0) |

|

No |

6 (35.3) |

6 (31.6) |

4 (40.0) |

|

Experience in COVID-19 vaccination |

Yes |

15 (88.2) |

17 (89.5) |

10 (100) |

|

No |

2 (11.8) |

2 (10.5) |

0 |

|

Thoughts on COVID-19 quarantine rules |

Positive |

2 (11.8) |

4 (21.1) |

3 (30.0) |

|

Average |

11 (64.7) |

11 (57.9) |

7 (70.0) |

|

Negative |

4 (23.5) |

4 (21.1) |

0 |

|

Correlation |

Factor Ⅰ |

1.00 |

|

|

|

Factor Ⅱ |

–.08 |

1.00 |

|

|

Factor Ⅲ |

.49 |

–.28 |

1.00 |

Table 3.Post-sorting Narratives of Three Factors

|

Respondent descriptions |

|

Factor I: Concerns about government policies related to COVID-19 (political perspectives) |

“I had COVID-19 vaccination 3 times as the government ordered, but I suffered too much from the side effects. The government told me to get vaccinated, but follow-up management was too lax. I will not get vaccinated again in the future.” (P3) |

|

“I went to the emergency room with a fever, but they only emphasized the government quarantine guidelines and prevented me from entering the hospital. Eventually, I got a shot outside the emergency room and returned home. The government and hospitals were outraged at the attitude of not taking responsibility for each other. The quarantine system was messed up.” (P29) |

|

“It was so nice to work from home. There is no stress from commuting, so I thought I should work harder. I hope the telecommuting system will continue even after the COVID-19 is over.” (P2) |

|

Factor II: Concerns about personal loss related to COVID-19 (personal perspectives) |

“Emergency COVID-19 relief funds were not helpful. It was not helpful for me either. It was more a problem for self-employed people. It breaks my heart to see so many people around me who have lost their jobs.” (P26) |

|

“Due to COVID-19, my company was in economic trouble, and the salary was not coming out properly. I was worried about my children’s tuition. Everything was messed up.” (P42) |

|

“I'm worried about other people too, but first of all, I'm worried about my financial life. I’ve been hit so hard financially that I don't have time to look around. COVID-19 has made me selfish.” (P40) |

|

Factor III: Concerns about social losses related to COVID-19 (social perspectives) |

“I believe in the government’s quarantine policy. I think that COVID-19 vaccination should be carried out for the public interest. Even if there is dissatisfaction, we must endure it for the well-being of society.” (P10) |

|

“The biggest problem is environmental pollution caused by disposable garbage. I feel guilty because there is so much garbage from delivered food and couriers. Now that COVID-19 has been eased a lot, we should refrain from using disposables.” (P11) |

REFERENCES

- 1. Chakraborty P, Kumar R, Karn S, Srivastava AK, Mondal P. The long-term impact of coronavirus disease 2019 on environmental health: a review study of the bi-directional effect. Bull Natl Res Cent. 2023;47(1):33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42269-023-01007-y

- 2. Lundstrom K. COVID-19 vaccines: where did we stand at the end of 2023? Viruses. 2024;16(2):203. https://doi.org/10.3390/v16020203

- 3. Roy N, Chaube R. Environmental impact of COVID-19 pandemic in India. Int J Biol Innov. 2021;3(1):48-57. https://doi.org/10.46505/IJBI.2021.3103

- 4. World Health Organization. WHO COVID-19 dashboard [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2024 [cited 2024 May 26]. Available from: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c

- 5. CoronaBoard. COVID-19 real-time board [Internet]. Seoul: CoronaBoard; 2023 [cited 2024 June 5]. Available from: https://coronaboard.kr/en/

- 6. World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19, Edition 158 [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2023 [cited 2024 May 1]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---1-september-2023

- 7. Choi SY, Ryu B, Jeong SJ, Jang M, An M, Park SY, et al. Characteristics and trends of COVID-19 deaths in the Republic of Korea (January 20, 2020–August 30, 2023). Public Health Wkly Rep. 2024;17(19):802-22. https://doi.org/10.56786/PHWR.2024.17.19.2

- 8. Gu M, Woo H, Sok S. Factors influencing coping skills of middle-aged adults in COVID-19, South Korea. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1248472. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2024.1248472

- 9. Liu YY, Yeh YC. Complementary and alternative medicines used by middle-aged to older Taiwanese adults to cope with stress during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(11):2250. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10112250

- 10. Chakrawarty A, Ranjan P, Klanidhi KB, Kaur D, Sarkar S, Sahu A, et al. Psycho-social and behavioral impact of COVID-19 on middle-aged and elderly individuals: a qualitative study. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:269. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_1458_20

- 11. de Feijter M, Kocevska D, Blanken TF, van der Velpen IF, Ikram MA, Luik AI. The network of psychosocial health in middle-aged and older adults during the first COVID-19 lockdown. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2022;57(12):2469-79. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02308-9

- 12. AlShurman BA, Khan AF, Mac C, Majeed M, Butt ZA. What demographic, social, and contextual factors influence the intention to use COVID-19 vaccines: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(17):9342. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18179342

- 13. El-Elimat T, AbuAlSamen MM, Almomani BA, Al-Sawalha NA, Alali FQ. Acceptance and attitudes toward COVID-19 vaccines: a cross-sectional study from Jordan. PloS One. 2021;16(4):e0250555. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0250555

- 14. Brown RT, Covinsky KE. Moving prevention of functional impairment upstream: is middle age an ideal time for intervention? Womens Midlife Health. 2020;6:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40695-020-00054-z

- 15. Infurna FJ, Gerstorf D, Lachman ME. Midlife in the 2020s: opportunities and challenges. Am Psychol. 2020;75(4):470-85. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000591

- 16. Korean Statistical Information Service. Republic of Korea by population [Internet]. Daejeon: Korean Statistical Information Service; 2023 [cited 2024 March 29]. Available from: https://kosis.kr/visual/populationKorea/PopulationDashBoardMain.do

- 17. Akhtar-Danesh N, Baumann A, Cordingley L. Q-methodology in nursing research: a promising method for the study of subjectivity. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30(6):759-73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945907312979

- 18. Churruca K, Ludlow K, Wu W, Gibbons K, Nguyen HM, Ellis LA, et al. A scoping review of Q-methodology in healthcare research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):125. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01309-7

- 19. Brown SR. Political subjectivity: application of Q methodology in political science. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1980.

- 20. Hensel D, Toronto C, Lawless J, Burgess J. A scoping review of Q methodology nursing education studies. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;109:105220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105220

- 21. Dziopa F, Ahern K. A systematic literature review of the applications of Q-technique and its methodology. Methodology. 2011;7(2):39-55. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000021

- 22. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-57. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- 23. Elhadi M, Alsoufi A, Alhadi A, Hmeida A, Alshareea E, Dokali M, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and acceptance of healthcare workers and the public regarding the COVID-19 vaccine: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):955. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10987-3

- 24. Islam MR, Hasan M, Nasreen W, Tushar MI, Bhuiyan MA. The COVID-19 vaccination experience in Bangladesh: findings from a cross-sectional study. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2021;35:20587384211065628. https://doi.org/10.1177/20587384211065628

- 25. Kim YK, Lim YG, Boo YJ. Factors affecting the practice of coronavirus (COVID-19) in a community population. J Korea Acad Ind Coop Soc. 2021;22(8):478-85. https://doi.org/10.5762/KAIS.2021.22.8.478

- 26. Statistics Korea. Employment trends in June 2021 [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2022 [cited 2024 May 2]. Available from: https://www.gov.kr/portal/gvrnPublish/view/H2107000000811332

- 27. Shon BD, Moon HJ. Who suffers the most financial hardships due to COVID-19? Korean J Soc Welf. 2021;73(3):9-31. https://doi.org/10.20970/kasw.2021.73.3.001

- 28. Koyama S, Aida J, Mori Y, Okawa S, Odani S, Miyashiro I. COVID-19 effects on income and dental visits: a cross-sectional study. JDR Clin Trans Res. 2022;7(3):307-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/23800844221094479

- 29. Lee DH, Kim YJ, Lee DH, Hwang HH, Nam SK, Kim JY. The influence of public fear, and psycho-social experiences during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic on depression and anxiety in South Korea. Korean J Couns Psychother. 2020;32(4):2119-56. https://doi.org/10.23844/kjcp.2020.11.32.4.2119

- 30. Allington D, McAndrew S, Moxham-Hall V, Duffy B. Coronavirus conspiracy suspicions, general vaccine attitudes, trust and coronavirus information source as predictors of vaccine hesitancy among UK residents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med. 2023;53(1):236-47. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721001434

- 31. Carrieri V, Guthmuller S, Wubker A. Trust and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):9245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-35974-z

- 32. Hantoko D, Li X, Pariatamby A, Yoshikawa K, Horttanainen M, Yan M. Challenges and practices on waste management and disposal during COVID-19 pandemic. J Environ Manage. 2021;286:112140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2021.112140

- 33. Iranmanesh M, Ghobakhloo M, Nilashi M, Tseng ML, Senali MG, Abbasi GA. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on household food waste behaviour: a systematic review. Appetite. 2022;176:106127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2022.106127

- 34. Vasko Z, Ostojic A, Ben Hassen T, Berjan S, El Bilali H, Durdic I, et al. Food waste perceptions and reported behaviours during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Waste Manag Res. 2023;41(2):312-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734242X221122495

- 35. Ikiz E, Maclaren VW, Alfred E, Sivanesan S. Impact of COVID-19 on household waste flows, diversion and reuse: the case of multi-residential buildings in Toronto, Canada. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2021;164:105111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2020.105111