Abstract

-

Purpose

This study aimed to examine the effects of a post-discharge tailored telephone (TATE) follow-up program for patients with low health literacy (LHL) who had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention.

-

Methods

This pilot study employed a non-equivalent control group pretest–posttest design to evaluate the preliminary effects of a TATE follow-up program at a university hospital in Seoul. Data were collected from July 2020 to September 2021. A total of 51 patients were recruited, and 46 completed the study. Patients were divided into three groups: an intervention group with LHL, a control group with LHL, and a control group with high health literacy. The intervention group received two 15-minute phone calls as part of the TATE follow-up program.

-

Results

The TATE follow-up program significantly improved disease-related knowledge in the intervention group compared with the control groups (p=.001). The intervention group also reported significantly higher satisfaction with nursing services than the other two groups (p=.006). However, there were no significant differences in changes in health behavior adherence among the groups, although the intervention group with LHL showed the greatest increase of 17.5 points after the intervention.

-

Conclusion

This pilot study demonstrated that the TATE follow-up program was effective and feasible for improving disease-related knowledge and satisfaction with nursing services among patients with LHL. These findings highlight the importance of tailored transitional care interventions to support cardiovascular disease management and secondary prevention.

-

Key Words: Coronary artery disease; Health behavior; Health literacy; Knowledge; Telephone

INTRODUCTION

Coronary artery disease (CAD), a leading cause of death worldwide, has increased by 23.5% in South Korea over the past decade and now ranks as the second leading cause of mortality [

1]. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is commonly performed to treat CAD, but a substantial proportion of patients experience major cardiac events within a year after the procedure [

2]. These events include death, acute myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and in-stent restenosis, with contributing factors such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, discontinuation of prescribed medication, and smoking [

3]. Therefore, reducing the risk of major cardiac events requires active management of these risk factors by improving lifestyle habits such as medication adherence, diet, and physical activity after PCI [

4,

5].

Cardiac rehabilitation (CR), which integrates medical management, exercise training, and patient education, has been shown to improve prognosis and quality of life in patients with CAD [

6]. However, participation in CR remains low. In Korea, the participation rate is approximately 31%, and non-attenders tend to be older and less educated than attenders [

7]. Major barriers include logistical and socioeconomic factors such as distance to hospitals, transportation difficulties, cost, time constraints, and comorbidities, all of which hinder regular participation [

7]. These barriers underscore the need for alternative, accessible, and individualized education strategies for CAD patients after discharge.

Health literacy is a key element in programs aimed at reducing CAD risk and enhancing secondary prevention [

8]. It refers to an individual’s ability to obtain, process, and understand health information, influencing both health behaviors and overall outcomes [

9]. Individuals with low health literacy (LHL) may struggle to understand medical advice or navigate healthcare systems [

10], which can lead to lower participation and higher dropout rates in CR programs [

8].

As a result, these individuals face barriers to engagement and continued participation in rehabilitation services and may miss the physiological and psychosocial benefits following coronary events [

8]. Patients with LHL are particularly vulnerable because they often have difficulty interpreting health information, possess limited disease-related knowledge, and find it challenging to follow medical guidance [

10]. Consequently, they are less likely to adopt heart-healthy behaviors such as regular exercise, balanced nutrition, moderation of alcohol intake, smoking cessation, and stress management [

11]. Thus, health literacy serves as a crucial determinant of successful cardiovascular disease management [

9].

After PCI, many patients experience difficulties during the early recovery phase due to short hospital stays and limited interaction with healthcare providers [

12]. Busy ward environments and rapid patient turnover often prevent clinicians from providing individualized instruction or addressing specific concerns. Consequently, patients frequently leave the hospital without a clear understanding of how to manage their care at home [

12]. Older patients, in particular, report feeling confused, anxious, and helpless after discharge, as they struggle to comprehend their hospitalization experience and adapt to post-procedure life. Because discharge counseling is often brief, patients receive only fragmentary or superficial information about their medication, condition, and required lifestyle modifications [

12]. As a result, many feel unprepared for self-care and uncertain about how to apply medical advice to daily life.

In addition, these patients frequently demonstrate limited knowledge and misconceptions about their disease and risk factors [

13]. Those with LHL are especially disadvantaged, as they may fail to understand information presented with medical jargon or rapid explanations from healthcare professionals [

14]. Previous studies of Korean cardiovascular patients [

15] have reported that some individuals were unable to interpret prescription labels or were unsure which health information sources to trust due to the overwhelming volume of available materials. Early identification of such patients and the delivery of education tailored to their comprehension level are therefore essential for effective secondary prevention.

Telephone-based interventions have emerged as a feasible means of post-discharge education and follow-up support. These interventions enable continuous communication between patients and healthcare providers, reinforce disease-related knowledge, and promote adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors [

16]. Personalized education and counseling after discharge have also been shown to enhance satisfaction with nursing services [

17]. However, most existing telephone-based programs for PCI patients deliver standardized information that does not account for individual differences in health literacy.

To address this gap, the present study developed and evaluated the effectiveness of a tailored telephone (TATE) follow-up program specifically designed for PCI patients with LHL. The intervention aimed to provide individualized education and counseling adapted to each patient’s comprehension level to improve disease-related knowledge, adherence to health behaviors, and satisfaction with nursing services.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This pilot study adopted a non-equivalent control group pretest–posttest design to examine the effects of the TATE follow-up program. To ensure accurate evaluation, participants who underwent PCI were divided into three groups according to their health literacy levels: an intervention group with LHL (LHL-I), a control group with LHL (LHL-C), and a control group with high health literacy (HHL-C). This study was reported in accordance with the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) guidelines.

2. Setting and Samples

Recruitment took place at a university hospital in Seoul from March to August 2021. The target population comprised adult patients diagnosed with CAD who were hospitalized and had undergone PCI for the first time, with the ability to communicate via telephone. Among those who met the inclusion criteria, patients planning to participate in a CR program within one month after discharge, those who experienced severe arrhythmia following the procedure, and those with musculoskeletal or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease limiting physical activity were excluded.

In pilot studies, it is important that the sample reflects the characteristics of the target population for the main study. Experts generally recommend recruiting approximately 10% of the target sample size for the pilot [

18]. Accordingly, based on a previous study [

19] and recruitment feasibility during the study period, a total of 51 participants were enrolled, with 17 participants per group.

To minimize contamination between groups, the researcher first assessed participants’ health literacy levels and then sequentially assigned them to one of the three groups: 17 participants to the LHL-C, 17 to the HHL-C, and the remaining 17 to the LHL-I.

3. Measurements and Instruments

In this study, specialized health literacy tools were employed to identify patients with low levels of CAD-related health literacy. The original instruments—including the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) [

20], which evaluates linguistic health literacy; the short version of the Korean Functional Health Literacy Test (S-KHLT) [

21], which measures functional health literacy; and the Newest Vital Sign (NVS) [

22], which assesses the ability to understand food and nutrition information—were deemed unsuitable for CAD patients. Therefore, the researchers adapted and simplified these instruments for use in screening CAD patients in clinical settings. Furthermore, the REALM, originally requiring “yes” or “no” responses, was modified into a 4-point scale using the Korean Health Literacy Assessment Tool as a reference [

23]. The three adapted tools used as screening instruments comprised a total of 40 questions, with scores ranging from 0 to 100. Higher scores indicated higher health literacy.

Because the purpose of this study was to adapt and simplify existing tools for clinical screening, content validity was established through expert review rather than formal content validity index testing. The revised version maintained relevance, clarity, and conceptual consistency with the original tools through evaluation by a panel of experts, including two nursing professors certified as nurse practitioners and one medical professor who served as the cardiologist for the study participants. The first nursing expert was a senior nurse with extensive experience in acute and coronary care settings and longstanding research in cardiovascular health, tailored self-care interventions, and transitional care. The second nursing expert, a senior nurse and researcher, focused on health literacy, chronic disease management, and patient-centered education through biopsychosocial and digital health approaches. All experts agreed on the final revised version.

According to Davis et al. [

20], individuals scoring below 60 were classified as having LHL in this study. The instrument used demonstrated a Cronbach’s α of .95.

Socio-demographic data—including age, sex, education level, occupation, and monthly household income—and disease-related data such as diagnosis, comorbidities, smoking, and alcohol consumption were collected from medical records and questionnaires.

Disease-related knowledge was assessed using the Knowledge of Disease Questionnaire for CAD patients developed by Kim and Park [

24]. Because some CAD patients do not take cardiac stimulants, related items were removed, and other modifications were made to align with current clinical practice and the study’s objectives. Content validity was again reviewed by the same expert panel to ensure item relevance and clarity. The questionnaire consists of 29 items covering disease characteristics, risk factors, diet, medication, daily life, and exercise. Responses of “I don’t know” or incorrect answers were scored as 0, while correct answers were scored as 1. Higher total scores indicated greater disease-related knowledge, with possible scores ranging from 0 to 29. Cronbach’s α was .75 in the original study [

24] and .90 in this study.

Adherence to health behaviors was measured using the Korean version of the Health-Promoting Lifestyle Profile II, translated and modified by Seo and Hah [

25]. To suit patients who had undergone PCI for CAD, the tool was modified by removing the subdomains of spiritual growth and interpersonal relations and by replacing items referring to moderate or vigorous physical activity and weight management with items concerning light physical activity. The same expert panel reviewed the revisions to ensure clarity and relevance for post-PCI patients. The modified instrument included 19 items across four domains: health responsibility, physical activity, nutrition, and stress management. Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores reflecting greater adherence to health behaviors (range, 19–76). Cronbach’s α was .92 in the previous study [

25] and .90 in this study.

Satisfaction with nursing service was evaluated using the translated Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 [

17]. To better align with the study’s purpose, two items—such as those asking whether participants would want to receive the same service for other illnesses—were excluded, and remaining items were revised to reflect pre-discharge education and the TATE follow-up program. The same expert panel reviewed the adapted instrument for relevance and comprehensibility. The final version contained six items addressing the quality and usefulness of telephone counseling, adequacy of time provided, fulfillment of patient needs, likelihood of recommending the service to others, and overall satisfaction. Each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction with nursing services (range, 6–24). Cronbach’s α was .91 in both the previous study [

17] and this study.

Data collection and intervention were conducted directly by the researcher, who personally recruited all participants meeting the inclusion criteria. Based on participants’ health literacy survey results, 34 individuals with LHL were sequentially assigned to the LHL-C and LHL-I groups, with 17 participants in each, while 17 participants with HHL were assigned to the HHL-C.

At the study hospital, cardiovascular education is routinely provided to patients before discharge through a 30-minute session using a booklet, delivered by a cardiovascular education nurse. During the pretest phase, the researcher explained how to complete the health diary and collected baseline data through questionnaires and medical record review.

The TATE follow-up program was developed based on educational resources from the Korean Society of Cardiology, such as Our Family’s Heart Keeper, and previous studies involving CAD patients. The program followed a structured telephone counseling protocol [

16,

26]. All intervention sessions were conducted exclusively by the same researcher, who had five years of experience as a cardiovascular research nurse. Each session adhered to a predefined sequence of educational topics—including understanding CAD, physical activity, medication adherence, and dietary modification—to ensure consistency of delivery across participants. To maintain fidelity, the researcher strictly followed a standardized script and recorded session duration, participant responses, and content coverage immediately after each call.

Furuya et al. [

26] suggested that the first two weeks after hospital discharge are a critical period for telephone follow-up, as patients transition from hospital to home and require substantial support for lifestyle adjustment and medication adherence. Similarly, a prior study [

27] implemented telephone consultations within 2 to 5 days of PCI to promote early compliance with self-care behaviors. Considering these findings and the short hospital stays typical of PCI patients, this program included two sessions—one per week for two weeks—to provide timely, practical, and continuous support during the most vulnerable post-discharge period. Each counseling call lasted approximately 15 minutes, taking into account the average participant age of around 70 years and referring to the 10 to 20 minute duration used by Won [

28].

To provide tailored counseling, the researcher further assessed the intervention group’s health literacy level to identify their comprehension capabilities. Individualized consultations were prepared before each session. The researcher reviewed each participant’s discharge summary, baseline questionnaires, comorbidities, medication regimen, blood pressure, lipid profile, and lifestyle habits. Based on these data, a simple individualized counseling plan was developed for each participant, outlining priority topics and educational emphases according to personal risk factors and literacy levels.

During the first-week telephone counseling session, information was provided on understanding CAD, physical activity, and medication adherence, customized to each individual’s health literacy level. In the second week, the focus shifted to individualized risk factors for CAD and dietary modification using the Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension (DASH) plan, emphasizing a low-salt, low-fat, and high-fiber diet. Medication adherence was also reviewed, and any challenges in implementation were identified. If needed, strategies such as setting mobile phone alarms were discussed to enhance compliance.

Jung and Hwang [

29] reported that the average linguistic health literacy of Korean CAD patients corresponds to the 4th–6th grade level in elementary school. Accordingly, educational materials were adjusted to a reading level of grade 6 or below using the Korean Vocabulary Difficulty Analysis Program (Natmal Corporation, Seoul, Korea). Medical terminology was replaced with plain language, and the researcher used a slower speech rate to enhance comprehension.

The teach-back method was employed to verify and reinforce understanding after each telephone counseling session. After delivering the educational content, the researcher asked open-ended questions to evaluate participants’ comprehension in key areas such as disease understanding, medication management, exercise, and dietary control. For example, participants were asked questions such as, “Can you explain in your own words what coronary artery disease is?,” “When should you stop exercising immediately?,” and “What precautions should you follow when taking antiplatelet medication?” Participants restated the information in their own words to confirm understanding. When responses were inaccurate or incomplete, the researcher re-explained the material using simpler language and familiar examples until the participant demonstrated correct understanding. Each session concluded with a reflective question such as, “Is there anything you still find confusing or want to ask about your disease or daily management?” to encourage two-way communication and identify remaining uncertainties. This interactive and iterative process enabled the researcher to detect misunderstandings in real time and provide immediate, individualized re-education.

Additionally, the “Ask Me 3” framework developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (Boston, MA, USA) was incorporated to structure the delivery of essential educational content. This framework has been shown to improve patient knowledge after myocardial infarction when used as an educational tool [

30]. Instead of prompting participants to generate and ask the three questions themselves, the researcher organized the telephone education according to the three core Ask Me 3 questions: (1) “What is my main problem?”—explaining that the participant had CAD treated with PCI and required ongoing secondary prevention; (2) “What do I need to do?”—outlining specific lifestyle and treatment strategies, including smoking cessation, dietary control, weight management, physical activity, and medication adherence; and (3) “Why is it important for me to do this?”—emphasizing that these behaviors help prevent restenosis and reduce the risk of recurrent cardiac events.

Furthermore, all participants were provided with a health diary as a self-monitoring tool to record medication intake, DASH diet adherence, physical activity, and other health behaviors, as well as blood pressure measurements. During the telephone consultations, the researcher reviewed participants’ diary entries and encouraged consistent use to promote self-management behaviors.

The content validity of the TATE follow-up program was reviewed and confirmed by a panel of two nursing professors and one cardiologist. All experts agreed on the clarity, relevance, and appropriateness of the revised content. After incorporating their feedback, the final version of the program was completed (

Table 1).

The posttest was conducted 3 to 4 weeks after discharge. In the posttest evaluation, satisfaction with nursing service reflected different contexts between groups: for the control groups, it represented satisfaction with discharge education provided by the cardiovascular educator nurse, while for the intervention group, it evaluated satisfaction with the nursing services received through the TATE follow-up program.

5. Ethical Considerations

This study was not registered in a public clinical trial registry because it was a pilot, non-randomized intervention study that did not meet the criteria for clinical trial registration. However, ethical approval was obtained from the Korea University Anam Hospital’s Institutional Review Board (IRB No. K2020-1301-002) prior to data collection. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the study’s purpose, procedures, and voluntary participation. Confidentiality was maintained by assigning identification codes instead of names, and all data were stored in password-protected files accessible only to the research team. Participants were informed that they could withdraw at any time without any disadvantage regarding medical or nursing care, and anonymity was strictly preserved. As a token of appreciation, participants were given pedometers.

6. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of continuous variables was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. For variables that did not satisfy normality assumptions, nonparametric tests were applied. To examine baseline homogeneity among the three groups, descriptive statistics, the chi-square test, the Fisher exact test, one-way analysis of variance, and the Kruskal–Wallis test were used as appropriate. Post hoc analyses with Bonferroni correction were conducted for variables showing significant group differences, testing all pairwise comparisons among the LHL-I, LHL-C, and HHL-C groups.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the intervention, generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were applied to analyze disease-related knowledge, which showed a non-normal distribution. The GEE method was selected because it accounts for within-subject correlations and provides robust parameter estimates for repeated measures data that do not meet normality assumptions. In contrast, linear mixed models were used to analyze adherence to health behaviors, as these data met normality assumptions and required modeling of both fixed (group, time, and group×time interaction) and random (individual variability) effects.

Satisfaction with nursing service was analyzed using analysis of covariance, adjusting for age, with post hoc comparisons conducted using Bonferroni correction. Among the demographic variables, age was the only factor showing significant pairwise group differences in the Bonferroni post hoc test and was therefore included as a covariate in the model. Although education level and occupation also differed descriptively at baseline, they were not included due to the small pilot sample size and concerns about potential multicollinearity. This limitation may have introduced residual confounding.

RESULTS

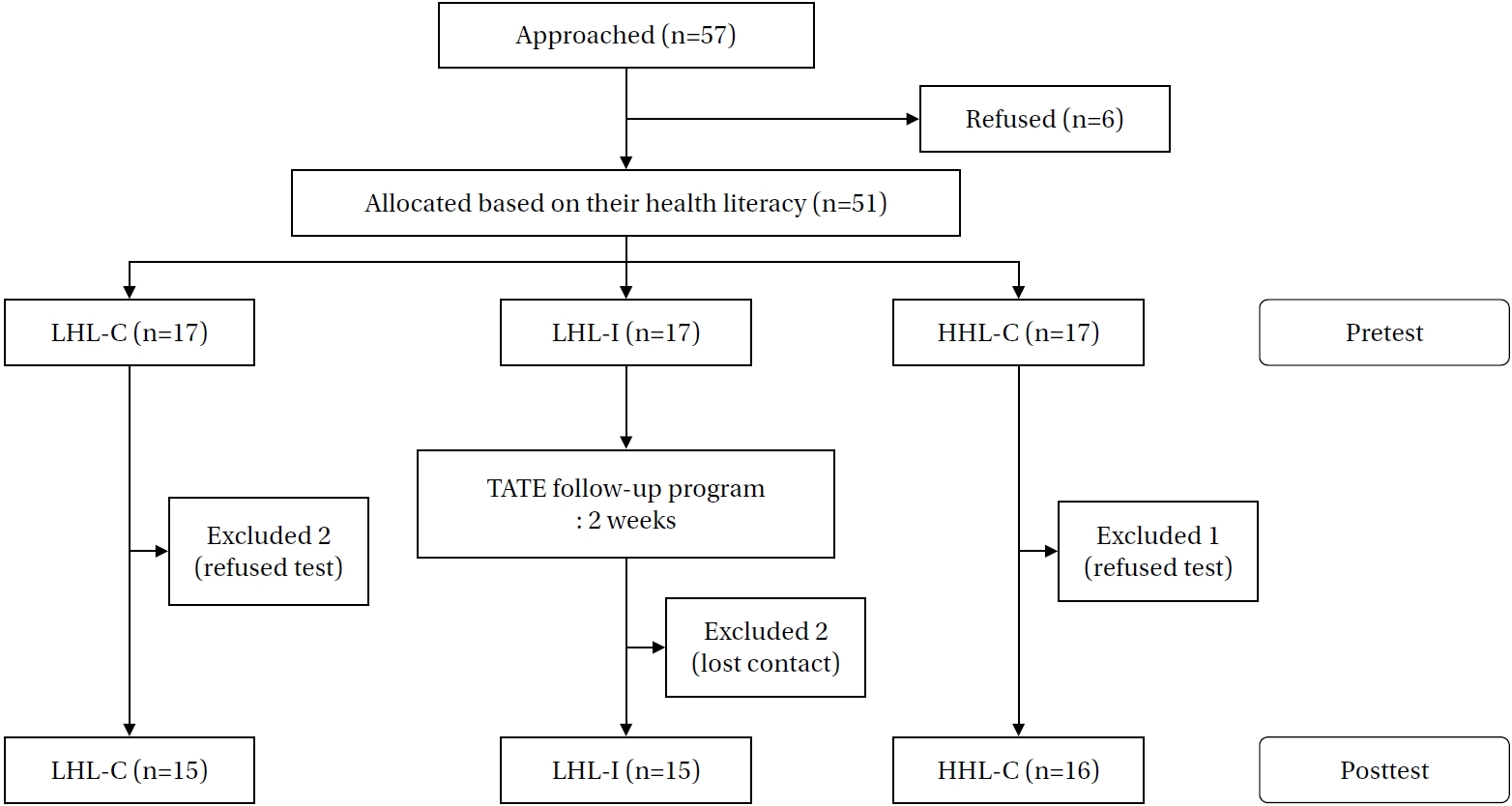

A total of 57 patients who underwent PCI were initially approached for participation. Of these, six declined to participate, resulting in 51 participants who completed the pretest. During the follow-up period, five participants (9.8%) dropped out before completing the posttest. Specifically, two participants (11.8%) in the LHL-C group and one participant (5.9%) in the HHL-C group declined to complete the posttest, while two participants (11.8%) in the LHL-I group were lost to contact during follow-up. Thus, the final analysis included 46 participants (90.2%): 15 in LHL-C, 16 in HHL-C, and 15 in LHL-I (

Figure 1).

Participants in the intervention group received tailored phone consultations once a week for two consecutive weeks, totaling two sessions, with an average duration of 16.17±7.30 minutes. The first session ranged from 12 to 27 minutes, and the second from 12 to 47 minutes. These findings confirm that the planned two-session intervention was feasible and well tolerated by participants.

According to the health literacy screening results, the total score among the 46 participants ranged from 6 to 88, with a mean of 53.48±18.44. The average scores for LHL-I, LHL-C, and HHL-C were 44.40±14.70, 42.47±14.08, and 72.31±7.17, respectively, confirming that the groups were appropriately classified according to literacy level. Detailed item-level analyses are provided in

Supplementary Data 1.

The age of the participants in this study ranged from 43 to 84 years. The mean ages for LHL-I, LHL-C, and HHL-C were 69.67±6.43, 70.13±10.81, and 59.19±7.94 years, respectively. Participants in the two LHL groups were significantly older than those in the HHL-C group (p=.001), indicating that lower health literacy was associated with older age. Most participants in the LHL-I and LHL-C groups (86.7% and 80.0%) were aged 65 years or older, compared with only 37.5% in the HHL-C group (p=.008).

The proportions of female participants were 33.3% in LHL-I, 46.7% in LHL-C, and 6.2% in HHL-C, demonstrating a significant sex difference among the groups (p=.029). Regarding education level, participants with middle school education or lower accounted for 46.7% of LHL-I , 60.0% of LHL-C, 6.3% of HHL-C, showing a significant group difference (p=.015). Employment status also differed significantly (p=.005), with more than half of the LHL-I and LHL-C participants being unemployed (66.7% and 53.3%, respectively), whereas 87.5% of HHL-C participants were employed. Although pairwise differences in education and occupation were not statistically significant after Bonferroni adjustment, descriptive trends indicated that participants with lower health literacy tended to have lower education levels and were less likely to be employed. These trends align with the typical demographic characteristics of individuals with limited health literacy, who are often older adults with lower educational attainment and fewer socioeconomic resources. The results of the homogeneity test thus showed that, despite some demographic differences across the three groups, the sample composition appropriately represented the target population for interventions focusing on individuals with LHL.

At the pretest, disease-related knowledge scores were significantly higher in the HHL-C group (mean=22.63) compared

with LHL-I (mean=18.07) and LHL-C (mean=14.40) (F=17.20,

p<.001). Although adherence to health behavior did not differ significantly among groups, the HHL-C group demonstrated numerically higher adherence scores, suggesting a possible association between higher health literacy and better baseline disease knowledge and self-care behavior (

Table 2).

In the LHL-I group, disease-related knowledge increased significantly by 6.86 points to 25.31 after the intervention, a significantly greater improvement than in the LHL-C (increase of 3.53) and HHL-C (increase of 1.88) groups (

χ2=13.60,

p=.001) (

Table 3). These results indicate that the TATE follow-up program effectively enhanced disease-related understanding among patients with LHL. The marked improvement underscores the importance of literacy-sensitive, individualized telephone counseling in bridging comprehension gaps that frequently hinder effective post-discharge cardiac care.

In contrast, no significant differences were observed among groups in changes in adherence to health behavior (F=1.93,

p=.157). Nevertheless, the LHL-I group exhibited the greatest increase, from 44.35 to 61.82 (a rise of 17.47 points), compared with increases of 10.80 (to 51.31) in LHL-C and 10.69 (to 57.45) in HHL-C (

Table 3). This upward trend across all groups suggests that participation in the study and enhanced disease awareness may have contributed to improved health behaviors overall, even though the two-week intervention period was likely insufficient to achieve statistically significant behavioral changes.

The satisfaction-with-nursing-service scores were 22.47 for LHL-I, 19.07 for LHL-C, and 20.38 for HHL-C, showing a significant difference among the groups (F=10.20,

p=.003). Post hoc analysis revealed that satisfaction with nursing service in the LHL-I group was significantly higher than in both control groups (a>b, c) (

Table 4). This result indicates that the tailored and interactive follow-up approach was well received by patients with LHL, likely because it provided a sense of individualized attention and reassurance during the vulnerable post-discharge transition period.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the effectiveness of the TATE follow-up program developed for patients with LHL who underwent PCI for CAD. The intervention group (LHL-I) demonstrated significantly greater improvement in disease-related knowledge and higher posttest satisfaction with nursing services than the two control groups, confirming the effectiveness of a literacy-tailored, telephone-based follow-up intervention. Participants with LHL in this study were mainly older adults with lower education levels and employment rates compared to those with HHL (HHL-C). These characteristics are consistent with previous studies [

31-

33] showing that aging, low educational attainment, and unemployment are associated with limited health literacy. These findings highlight the importance of tailoring educational interventions to meet the cognitive, linguistic, and informational needs of older adults.

The significant improvement in disease-related knowledge among the LHL-I group can be explained by several mechanisms. First, the structured, literacy-adjusted approach—using simplified language, slower speech, and teach-back techniques—likely enhanced comprehension and retention. Second, the Ask Me 3 framework and the two-session design provided opportunities for repetition and reinforcement, which are known to facilitate learning among individuals with limited literacy. Third, individualized counseling that considered patients’ comorbidities, medication profiles, and lifestyle factors increased relevance and engagement, thereby supporting active learning. Collectively, these mechanisms demonstrate how literacy-sensitive interventions can effectively reduce the knowledge gap between LHL and HHL patients, aligning with prior evidence that tailored education improves chronic disease management [

34].

Although adherence to health behaviors improved in all three groups, the differences were not statistically significant. Several factors may explain this outcome. The short two-week intervention period may not have been sufficient for measurable behavioral changes to occur, as previous studies have conducted interventions lasting 6 to 8 weeks [

16]. Additionally, the small pilot sample may have limited statistical power to detect differences between groups, especially given the variability of individual lifestyles. Moreover, adherence was assessed using self-report measures, which are subject to recall and social desirability biases. Because behavioral change generally requires sustained reinforcement and environmental support, future research should employ longer follow-up periods and objective compliance measures, such as wearable activity trackers, to capture behavioral outcomes more accurately.

The higher satisfaction with nursing services observed in the LHL-I group likely reflects both informational and emotional support. The first four weeks after discharge are not only a period of physical recovery and adaptation but also a time marked by anxiety about recurrence, depression, uncertainty about disease progression, and adjustment to new medication routines. The TATE follow-up program, which provided two post-discharge phone calls during this vulnerable period, was associated with high satisfaction among intervention participants. The individualized telephone consultations offered a platform for older patients to ask questions and receive reassurance, addressing both knowledge gaps and emotional concerns in the early recovery phase. Consistent with findings by Walters et al. [

35], this empathetic, one-on-one communication via telephone mentoring enhances patients’ confidence, self-management motivation, and overall satisfaction with care—particularly among older adults who may feel less confident interacting with healthcare providers.

In terms of clinical feasibility, the TATE program was delivered entirely by a single cardiovascular nurse using structured protocols, suggesting that such interventions can be feasibly incorporated into routine nursing workflows. However, in real-world practice, allocating sufficient time for telephone consultations during regular working hours may be challenging, particularly in high-acuity hospital settings. To improve sustainability, healthcare institutions could integrate literacy-tailored interventions into transitional care programs, supported by experienced nurse educators or telemedicine teams. Despite these logistical challenges, the program’s high satisfaction rates and significant improvements in knowledge indicate that this approach is both effective and meaningful for patient-centered nursing care.

The originality of this study lies in its health literacy–based strategies tailored to individual patient needs to enhance self-management adherence by improving disease knowledge during the hospital-to-home transition. The findings provide new evidence supporting literacy-sensitive education within cardiovascular transitional care, particularly for patients with LHL—a population often overlooked in standard discharge education. This focus on differentiated health literacy represents an important contribution to existing literature.

There are several limitations to this study. First, it was conducted at a single site with a small pilot sample, which limits generalizability. Second, the short intervention and follow-up periods may have reduced the likelihood of detecting behavioral changes. Third, adherence data were self-reported and thus potentially affected by reporting bias. Fourth, the absence of randomization and residual confounding—particularly from variables such as education and occupation that were not included in the statistical models—may have influenced the results. Finally, validating these findings will require large-scale randomized controlled trials with extended follow-up and objective adherence measurements in future research.

Based on these findings, several recommendations can be made for clinical nursing practice and future studies. First, nurses should assess patients’ health literacy during hospitalization and provide tailored education and follow-up according to individual needs. Second, healthcare institutions should integrate structured, telephone-based follow-up interventions into transitional care services, particularly for older adults and those with limited health literacy. Finally, future research should involve larger and more diverse samples, longer intervention periods, and objective measures of adherence to evaluate the long-term effects of tailored interventions on health behaviors and cardiovascular outcomes.

CONCLUSION

This pilot study underscores the value of tailored transitional care interventions that address patients’ specific health literacy levels and cardiovascular risk factors. It also emphasizes the importance of continuity in nursing care that extends beyond acute treatment to support secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. The TATE program demonstrates a feasible and effective approach to improving patient outcomes during the critical post-discharge transition period through individualized interventions for patients with LHL. This approach not only meets immediate educational needs but also lays the foundation for sustained health behavior changes that can reduce cardiovascular risk over time.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and design - MK, NMS, and JP; data curation and methodology - MK; formal analysis and methodology - MK and NMS; funding acquisition - NMS; resources - JP; project administration - NMS; supervision and validation - NMS and JP; software - MK; drafting and critical revision of the manuscript - MK, NMS, and JP.

-

Funding

This study was funded by the Korea University Institute of Nursing Research.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Dr. Soon-Jun Hong for facilitating the recruitment of study patients. This article is a revision of the Myoungjoo Kang’s master’s thesis from Korea University.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplement Data 1.

Additional Analysis of Percentage of Correct Answers for Functional Health Literacy Test and Nutrition Labeling Health Literacy Test

kjan-2025-0827-Supplemental-Data-1.pdf

Figure 1.Flow chart of recruitment and follow-up process. HHL-C=control group 2 with high health literacy; LHL-C=control group 1 with low health literacy; LHL-I=intervention group with low health literacy; TATE=tailored telephone.

Table 1.Content of the TATE Follow-up Program

|

Week |

Topic |

Contents |

Time (min) |

|

1 |

Orientation |

Introduce and greet the researcher |

1 |

|

Check the status of the subject and writing health diary |

|

Ask Me 3 |

Explain the need for secondary prevention after PCI |

1 |

|

Understanding CAD |

Provide information on the cause, type, symptoms of CAD, and precautions after discharge |

5 |

|

Health behavior |

Educate precautions for physical activity and encourage records of the amount of walking |

5 |

|

Guidelines for precautions on taking medication and how to take antithrombotic and nitroglycerin |

|

Inspire subjects to follow medication protocol |

|

Teach-back |

Confirm the subject’s perception of the information provided and retrain and question and answer |

2 |

|

Termination |

Encourage keeping a health diary |

1 |

|

Make an appointment for the next phone call schedule |

|

2 |

Introduction |

Introduce and greet a researcher |

1 |

|

Check the status of the subject and writing health diary |

|

Ask Me 3 |

Explain the need for secondary prevention after PCI |

1 |

|

Risk factors of CAD |

Provide information on smoking, obesity, stress, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, and so on |

5 |

|

Health behavior |

Educate a basic diet and food-related to atherosclerosis |

5 |

|

Inspire DASH diet |

|

Encourage records the amount of walking |

|

Check and encourage adherence to medication using a health diary |

|

Teach-back |

Confirm the subject’s perception of the information provided and retrain and question and answer |

2 |

|

Termination |

Encourage keeping a health diary |

1 |

|

Check an appointment for the next outpatient schedule |

Table 2.Comparison of Participants’ Socio-demographic, Disease-Related Characteristics, and Baseline Disease Knowledge and Health Behavior Adherence According to Health Literacy Level

|

Variables |

Total (n=46) |

LHL-Ia (n=15) |

LHL-Cb (n=15) |

HHL-Cc (n=16) |

F |

p

|

Bonferroni |

|

n (%) or mean ±SD |

|

Age (year) (range 43–84) |

66.17±9.84 |

69.67±6.43 |

70.13±10.81 |

59.19±7.94 |

14.59 |

.001 |

a, b>c |

|

<65 |

15 (32.6) |

2 (13.3) |

3 (20.0) |

10 (62.5) |

9.39 |

.008 |

|

|

≥65 |

31 (67.4) |

13 (86.7) |

12 (80.0) |

6 (37.5) |

|

|

|

|

Sex |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Men |

33 (71.7) |

10 (66.7) |

8 (53.3) |

15 (93.8) |

6.75 |

.029 |

|

|

Women |

13 (28.3) |

5 (33.3) |

7 (46.7) |

1 (6.2) |

|

|

|

|

Education level |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≤Middle school |

17 (37.0) |

7 (46.7) |

9 (60.0) |

1 (6.3) |

12.05 |

.015 |

|

|

High school |

14 (30.4) |

5 (33.3) |

3 (20.0) |

6 (37.5) |

|

|

|

|

≥College |

15 (32.6) |

3 (20.0) |

3 (20.0) |

9 (56.3) |

|

|

|

|

Occupation |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Yes |

26 (56.5) |

5 (33.3) |

7 (46.7) |

14 (87.5) |

10.12 |

.005 |

|

|

No |

20 (43.5) |

10 (66.7) |

8 (53.3) |

2 (12.5) |

|

|

|

|

Monthly household income (KRW) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

≤2,000,000 |

24 (52.2) |

10 (66.7) |

9 (60.0) |

5 (31.3) |

4.64 |

.324 |

|

|

2,010,000–4,000,000 |

13 (28.3) |

3 (20.0) |

3 (20.0) |

7 (43.8) |

|

|

|

|

≥4,010,000 |

9 (19.6) |

2 (13.3) |

3 (20.0) |

4 (25.0) |

|

|

|

|

Diagnosis |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

STEMI |

11 (23.9) |

5 (33.3) |

3 (20.0) |

3 (18.8) |

12.07 |

.057 |

|

|

NSTEMI |

4 (8.7) |

3 (20.0) |

1 (6.7) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

|

|

Unstable angina |

3 (6.5) |

2 (13.3) |

1 (6.7) |

0 (0.0) |

|

|

|

|

Stable angina |

27 (58.7) |

4 (26.7) |

10 (66.7) |

13 (81.3) |

|

|

|

|

Mixed angina |

1 (2.2) |

1 (6.7) |

0 (0.0) |

0 (0) |

|

|

|

|

Comorbidity, yes |

39 (84.8) |

12 (80.0) |

14 (93.3) |

13 (81.3) |

1.34 |

.670 |

|

|

Numbers |

1.96±1.28 |

2.00±1.36 |

2.27±1.22 |

1.63±1.26 |

|

|

|

|

Hypertension |

31 (67.4) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Hyperlipidemia |

20 (43.5) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Diabetes mellitus |

15 (32.6) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Smoking, yes |

8 (17.4) |

3 (20.0) |

1 (6.7) |

4 (25.0) |

1.93 |

.491 |

|

|

Drinking, yes |

15 (32.6) |

6 (40.0) |

2 (13.3) |

7 (43.8) |

3.88 |

.184 |

|

|

Disease-related knowledge |

|

18.07±5.64 |

14.40±7.00 |

22.63±2.83 |

17.20 |

<.001 |

a, b>c |

|

Adherence to health behavior |

|

44.67±13.47 |

40.87±9.61 |

46.13±9.30 |

0.95 |

.396 |

|

Table 3.Changes in Disease-Related Knowledge and Adherence to Health Behavior between Pretest and Posttest Based on Health Literacy Levels

|

Variables |

Group |

Mean (SD) |

Group |

Time |

Age |

Group×time |

|

Pre |

Post |

Post-Pre |

χ2/F |

p

|

χ2/F |

p

|

χ2/F |

p

|

χ2/F |

p

|

|

Disease-related knowledge†

|

LHL-I |

18.45 (0.42) |

25.31 (0.80) |

6.86 (4.55) |

25.11 |

<.001 |

37.66 |

<.001 |

1.70 |

.192 |

13.60 |

.001 |

|

LHL-C |

17.36 (0.67) |

20.89 (1.04) |

3.53 (5.90) |

|

HHL-C |

19.49 (0.42) |

21.37 (0.78) |

1.88 (3.05) |

|

Adherence to health behavior‡

|

LHL-I |

44.35 (2.55) |

61.82 (2.55) |

17.47 (10.16 |

3.38 |

.044 |

65.49 |

<.001 |

0.40 |

.529 |

1.93 |

.157 |

|

LHL-C |

40.51 (2.56) |

51.31 (2.56) |

10.80 (11.79) |

|

HHL-C |

46.76 (2.62) |

57.45 (2.62) |

10.69 (10.64) |

Table 4.Differences in Satisfaction with Nursing Care

|

Variables |

Mean (SD) |

F |

p

|

Bonferroni |

|

LHL-Ia (n=15) |

LHL-Cb (n=15) |

HHL-Cc (n=16) |

|

Satisfaction with nursing care |

22.47 (1.77) |

19.07 (2.84) |

20.38 (3.50) |

10.20 |

.003 |

a>b, c |

REFERENCES

- 1. Statistics Korea. Cause-of-death statistics in 2021 [Internet]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2022 [cited 2023 November 19]. Available from: https://kostat.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10301060200&bid=218&act=view&list_no=420715

- 2. Madhavan MV, Kirtane AJ, Redfors B, Genereux P, Ben-Yehuda O, Palmerini T, et al. Stent-related adverse events >1 year after percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(6):590-604. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2019.11.058

- 3. Nakanishi R, Berman DS, Budoff MJ, Gransar H, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, et al. Current but not past smoking increases the risk of cardiac events: insights from coronary computed tomographic angiography. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(17):1031-40. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv013

- 4. Anderson L, Oldridge N, Thompson DR, Zwisler AD, Rees K, Martin N, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for coronary heart disease: cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(1):1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.044

- 5. Huber CA, Meyer MR, Steffel J, Blozik E, Reich O, Rosemann T. Post-myocardial infarction (MI) care: medication adherence for secondary prevention after MI in a large real-world population. Clin Ther. 2019;41(1):107-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.11.012

- 6. Kim C, Sung J, Lee JH, Kim WS, Lee GJ, Jee S, et al. Clinical practice guideline for cardiac rehabilitation in Korea: recommendations for cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention after acute coronary syndrome. Korean Circ J. 2019;49(11):1066-111. https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2019.0194

- 7. Im HW, Baek S, Jee S, Ahn JM, Park MW, Kim WS. Barriers to outpatient hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation in Korean patients with acute coronary syndrome. Ann Rehabil Med. 2018;42(1):154-65. https://doi.org/10.5535/arm.2018.42.1.154

- 8. Magnani JW, Mujahid MS, Aronow HD, Cene CW, Dickson VV, Havranek E, et al. Health literacy and cardiovascular disease: fundamental relevance to primary and secondary prevention: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2018;138(2):e48-74. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000579

- 9. Aaby A, Friis K, Christensen B, Rowlands G, Maindal HT. Health literacy is associated with health behaviour and self-reported health: a large population-based study in individuals with cardiovascular disease. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2017;24(17):1880-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487317729538

- 10. Chehuen Neto JA, Costa LA, Estevanin GM, Bignoto TC, Vieira CI, Pinto FA, et al. Functional health literacy in chronic cardiovascular patients. Cien Saude Colet. 2019;24(3):1121-32. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232018243.02212017

- 11. Lu M, Xia H, Ma J, Lin Y, Zhang X, Shen Y, et al. Relationship between adherence to secondary prevention and health literacy, self-efficacy and disease knowledge among patients with coronary artery disease in China. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2020;19(3):230-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515119880059

- 12. Valaker I, Norekval TM, Raholm MB, Nordrehaug JE, Rotevatn S, Fridlund B. Continuity of care after percutaneous coronary intervention: the patient's perspective across secondary and primary care settings. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2017;16(5):444-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515117690298

- 13. Perk J, Hambraeus K, Burell G, Carlsson R, Johansson P, Lisspers J. Study of patient information after percutaneous coronary intervention (SPICI): should prevention programmes become more effective? EuroIntervention. 2015;10(11):e1-7. https://doi.org/10.4244/EIJV10I11A223

- 14. Kripalani S, Jacobson TA, Mugalla IC, Cawthon CR, Niesner KJ, Vaccarino V. Health literacy and the quality of physician-patient communication during hospitalization. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(5):269-75. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.667

- 15. Sim JE, Hwang SY. Concept analysis of health literacy for patients with cardiovascular disease using hybrid model. J Korean Acad Community Health Nurs. 2019;30(4):494-507. https://doi.org/10.12799/jkachn.2019.30.4.494

- 16. Kim SY, Kim MY. Development and effectiveness of tailored education and counseling program for patients with coronary artery disease undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2017;29(5):547-59. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2017.29.5.547

- 17. Kim HJ, Park YH. The effects of discharge planning for the elderly with pulmonary disease in the emergency room. J Korean Crit Care Nurs. 2014;7(1):24-32.

- 18. Connelly LM. Pilot studies. Medsurg Nurs. 2008;17(6):411-2.

- 19. Rodriguez MA, Friedberg JP, DiGiovanni A, Wang B, Wylie-Rosett J, Hyoung S, et al. A tailored behavioral intervention to promote adherence to the DASH diet. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(4):659-70. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.43.4.1

- 20. Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, Murphy PW, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25(6):391-5.

- 21. Kim SH. Validation of the short version of Korean functional health literacy test. Int J Nurs Pract. 2017;23(4):e12559. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12559

- 22. Weiss BD, Mays MZ, Martz W, Castro KM, DeWalt DA, Pignone MP, et al. Quick assessment of literacy in primary care: the Newest Vital Sign. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):514-22. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.405

- 23. Lee SH, Choi EH, Je MJ, Han HS, Park BK, Kim SS. Comparison of two versions of KHLAT for improvement strategies. Korean J Health Educ Promot. 2011;28(3):57-65.

- 24. Kim NH, Park OJ. A study on coronary artery restenosis, knowledge related-disease and compliance in the patients received follow-up coronary angiogram after coronary intervention. Nurs Health Issues. 2009;14(1):97-108.

- 25. Seo HM, Hah YS. A study of factors influencing on health promoting lifestyle in the elderly: application of Pender's health promotion model. J Korean Acad Nurs. 2004;34(7):1288-97. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.2004.34.7.1288

- 26. Furuya RK, Mata LR, Veras VS, Appoloni AH, Dantas RA, Silveira RC, et al. Original research: telephone follow-up for patients after myocardial revascularization: a systematic review. Am J Nurs. 2013;113(5):28-31. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000429756.00008.ca

- 27. Mols RE, Hald M, Vistisen HS, Lomborg K, Maeng M. Nurse-led motivational telephone follow-up after same-day percutaneous coronary intervention reduces readmission and contacts to general practice. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2019;34(3):222-30. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0000000000000566

- 28. Won MH. Effect of education and counselling-based cardiac rehabilitation program on cardiovascular risk, health behavior and quality of life in elderly with coronary artery disease. J Korea Contents Assoc. 2015;15(6):303-13. https://doi.org/10.5392/jkca.2015.15.06.303

- 29. Jung EY, Hwang SK. Health literacy and health behavior compliance in patients with coronary artery disease. Korean J Adult Nurs. 2015;27(3):251-61. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2015.27.3.251

- 30. Winiger AM, Shue-McGuffin K, Moore-Gibbs A, Jordan K, Blanchard A. Implementation of an Ask Me 3 ® education video to improve outcomes in post-myocardial infarction patients. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2021;8:100253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpc.2021.100253

- 31. Peltzer S, Hellstern M, Genske A, Junger S, Woopen C, Albus C. Health literacy in persons at risk of and patients with coronary heart disease: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2020;245:112711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112711

- 32. Ghisi GL, Chaves GS, Britto RR, Oh P. Health literacy and coronary artery disease: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(2):177-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.09.002

- 33. Suhail M, Saeed H, Saleem Z, Younas S, Hashmi FK, Rasool F, et al. Association of health literacy and medication adherence with health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with ischemic heart disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):118. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-021-01761-5

- 34. Schapira MM, Swartz S, Ganschow PS, Jacobs EA, Neuner JM, Walker CM, et al. Tailoring educational and behavioral interventions to level of health literacy: a systematic review. MDM Policy Pract. 2017;2(1):2381468317714474. https://doi.org/10.1177/2381468317714474

- 35. Walters JA, Cameron-Tucker H, Courtney-Pratt H, Nelson M, Robinson A, Scott J, et al. Supporting health behaviour change in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease with telephone health-mentoring: insights from a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:55. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-13-55