Abstract

-

Purpose

This study investigated differences in the use of life-sustaining treatments during the last six months of life between older adults covered by the National Health Insurance (NHI) and those enrolled in the Medical Aid (MA) program.

-

Methods

A retrospective cohort design was applied using national claims data from the National Health Insurance Service. The study population included individuals aged ≥65 years who died in 2023, with 286,319 decedents (247,935 with NHI and 38,384 with MA) analyzed. We compared hospitalization frequency and duration, intensive care unit (ICU) stays, and the use of life-sustaining treatments, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation, mechanical ventilation, hemodialysis, chemotherapy, transfusions, and vasopressors, between NHI and MA groups. Logistic regression analyses were conducted with adjustments for age, sex, comorbidities, place of death, and advance care planning status.

-

Results

Completion rates of advance directives and physician orders for life-sustaining treatment were lower in MA than in NHI decedents. MA decedents had fewer admissions but significantly longer hospital and ICU stays than NHI decedents. They were less likely to receive mechanical ventilation, chemotherapy, transfusion, and vasopressors but more likely to undergo hemodialysis.

-

Conclusion

Substantial disparities exist in end-of-life care by insurance type, suggesting that socioeconomic inequalities and reimbursement structures influence patterns of intensive care near the end of life. Targeted interventions are needed to ensure equitable, patient-centered end-of-life care for socioeconomically vulnerable older adults.

-

Key Words: Health insurance; Insurance claim review; Medicaid; Terminal care

INTRODUCTION

Socioeconomic status (SES) is a critical determinant of disparities in access to and utilization of healthcare services, including life-sustaining treatments at the end of life (EOL), even in countries with universal healthcare or robust public health systems [

1-

3]. Health insurance type—an indicator of SES—can substantially affect both access to care and treatment decisions [

4]. Differences in the use of life-sustaining treatments and EOL care across insurance types reflect not only service availability but also broader issues of healthcare equity and patient-centered care [

5].

In Korea, 91% of the population is enrolled in the National Health Insurance (NHI) scheme, which provides universal health coverage [

6]. The government supports individuals unable to afford insurance through the Medical Aid (MA) program. Most MA beneficiaries are older adults with multiple chronic conditions whose financial hardship frequently hinders appropriate and timely treatment, leading to health deterioration [

7]. These clinical and economic constraints may result either in underutilization of necessary active treatments or in the delivery of unnecessary life-sustaining interventions. International studies have reported that low SES and Medicaid coverage are associated with lower utilization of hospice services and greater reliance on intensive care at the EOL [

8-

10].

Although quantitative research increasingly documents disparities in palliative care access and life-sustaining treatment use across socioeconomic groups [

8-

10], little is known about the experiences of people with low SES in EOL care. Compared with individuals at the highest SES level, those at the lowest level are more likely to die in hospitals rather than at home or in hospices and to receive acute hospital-based care during the last three months of life [

11]. This trend indicates a higher likelihood of receiving life-sustaining treatments among those with low SES. Aggressive EOL care is associated with reduced quality of life for patients and families and contributes to high medical expenditures during the last months of life, further straining the healthcare system [

12,

13].

Despite substantial research on EOL care in terminally ill populations, particularly among those with cancer or dementia [

14,

15], few studies have specifically examined EOL care in individuals with low SES, such as MA beneficiaries. Understanding patterns of healthcare utilization and life-sustaining treatment in this group, characterized by multiple chronic conditions and often lacking familial support, is essential to improving the quality of EOL care. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate differences in healthcare utilization, focusing on hospitalizations, intensive care unit (ICU) stays, and life-sustaining treatments, during the last six months of life between older adults with NHI and those with MA, using national claims data.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This study used a retrospective cohort design based on claims data from the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) of South Korea. Study procedures and findings were reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist [

16].

Claims data were obtained from the NHIS database, a comprehensive national resource that integrates information from both the NHIS and the MA program. The database contains extensive records, including qualification data (e.g., age, sex, income, region, and qualification type), claims data (e.g., procedure, diagnostic, and medication codes), health checkup results, death-related information, and details about medical institutions.

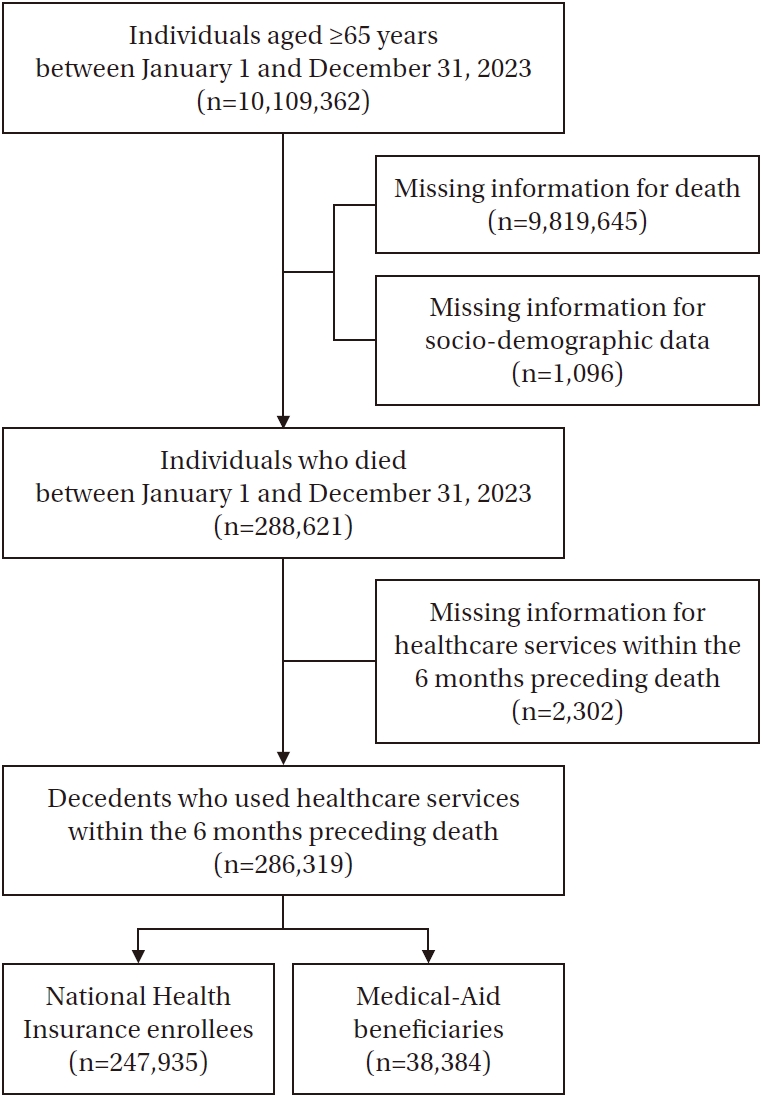

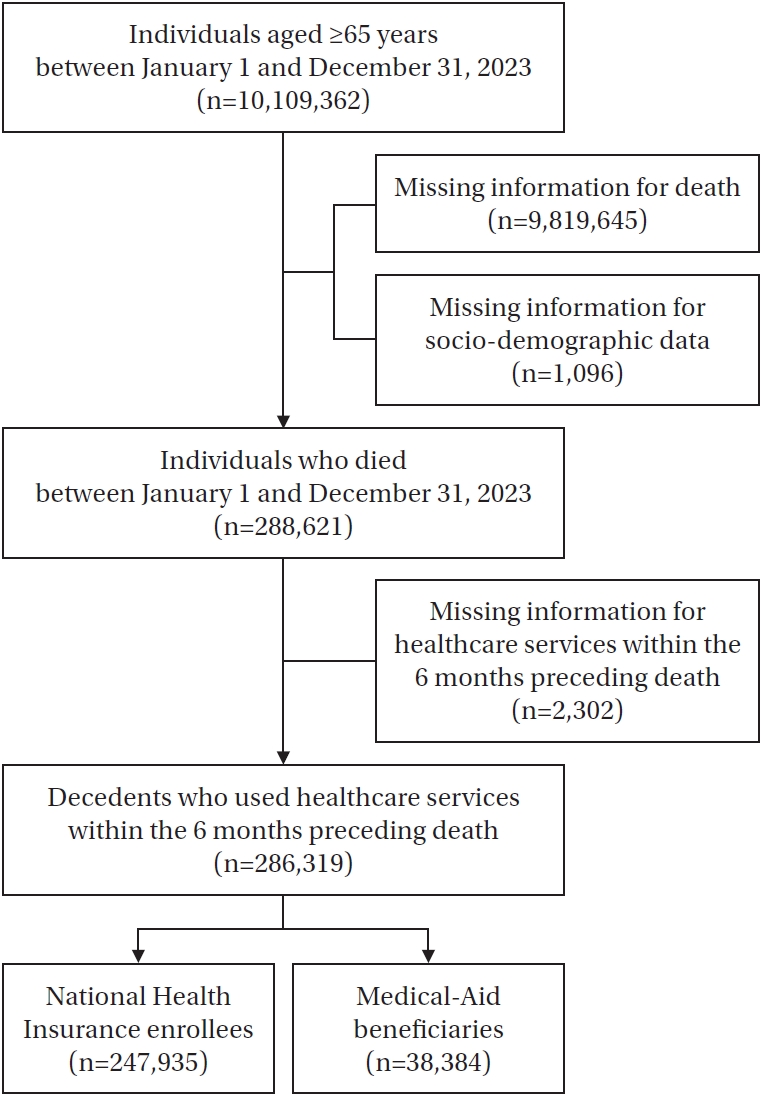

The study cohort consisted of 286,319 individuals aged ≥65 years who died between January 1 and December 31, 2023, and who had used healthcare services within six months before death (

Figure 1). To assess healthcare utilization—including life-sustaining treatment—during this period, each individual’s medical observation window was defined as the six months preceding their date of death. Hospitalization and life-sustaining treatment utilization were evaluated within 0–30, 0–90, and 0–180 days before death.

1) Hospital and ICU admissions and length of stay

Hospitalizations and ICU admissions were defined as the average frequency per person during each observation window. Hospitalization days and ICU stays were defined as the average duration per person within the same periods.

2) Life-sustaining treatment use

Life-sustaining treatments were identified using specific procedure codes, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), mechanical ventilation, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), hemodialysis, chemotherapy, transfusion, and vasopressors. These interventions are recognized as life-sustaining treatments under the Act on Hospice and Palliative Care and Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment for Patients at the End of Life (Life-Sustaining Treatment Decision Act) in South Korea (Act No. 19466, April 1, 2025) [

17]. ECMO was excluded from the analysis due to its extremely low use, accounting for <0.01% of all cases. Life-sustaining treatment use was defined as receiving at least one relevant treatment during a given observation window. Individuals who received the specified treatment at least once within 0–30, 0–90, or 0–180 days before death were coded as “1,” and those who did not receive the treatment were coded as “0.”

3) Covariates

Age was grouped into 65–74, 75–84, and ≥85 years. Geographic regions were classified into three tiers: large (metropolitan cities), medium (cities with or without administrative districts), and small (eup/myeon [town/township] areas within cities). The number of chronic diseases was categorized as 0, 1, 2, or ≥3. Chronic conditions included hypertension, diabetes, mental and behavioral disorders (including epilepsy), respiratory tuberculosis, heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, nervous system disease, malignant neoplasms, thyroid disease, liver disease (including chronic viral hepatitis), and chronic kidney disease. Disease severity was assessed using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) score [

18], categorized as 0, 1, 2, or ≥3. Place of death was grouped into tertiary hospitals, general hospitals, long-term care hospitals, and others. The presence of advance directives and physician orders for life-sustaining treatment was determined by whether participants had completed the documentation.

This study involved secondary analysis of existing data. It was exempted from ethics review by the Institutional Review Board of the first author’s university in South Korea (No. 2022-10-021).

5. Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive statistics, the chi-square test, and the independent t-test were applied to compare characteristics of NHI and MA decedents. Differences in the number of hospitalizations, ICU admissions, and length of stay during the 180 days before death were examined using independent t-tests. Use of life-sustaining treatments across NHI and MA groups was compared with descriptive statistics and chi-square tests for three timeframes (0–30, 0–90, and 0–180 days before death). Logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the relative risk of life-sustaining treatment use within 180 days before death by insurance type, with results reported as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Multiple logistic regression models were adjusted for age, sex, CCI score, place of death, and completion of advance directives or physician orders for life-sustaining treatment.

RESULTS

1. Participants’ General Characteristics by Health Insurance Type

The final sample included 286,319 older adults who had died, with 247,935 covered by NHI and 38,384 enrolled in MA (

Table 1). The two groups showed statistically significant differences in demographic and clinical characteristics. More than half of the NHI decedents were males (50.8%), whereas most MA decedents were females (55.4%). The mean age was higher among NHI decedents (82.86±8.24) than among MA decedents (81.66±9.20). A substantial proportion of both groups were aged ≥85 years (45.8% in NHI and 41.6% in MA). The mean CCI score was also higher in MA decedents (0.33±0.88) than in NHI decedents (0.32±0.87). In both groups, the most frequent place of death was long-term care hospitals. Deaths in tertiary hospitals were more common among NHI decedents (16.9%) than among MA decedents (11.7%). Completion rates of advance directives (2.8% vs. 1.1%) and physician orders for life-sustaining treatment (1.0% vs. 0.9%) were both higher in the NHI group compared with the MA group.

Hospitalization and ICU admission patterns differed significantly between NHI and MA decedents (

Table 2). During the last 180 days of life, MA decedents had fewer hospital admissions than NHI decedents (5.25±4.57 vs. 6.08±5.44). However, despite fewer admissions, MA decedents had significantly longer cumulative hospital stays (45.86±88.77 days) compared with NHI decedents (30.85±68.45 days). Similarly, the mean number of ICU admissions was slightly higher among MA decedents (1.47±0.93) than NHI decedents (1.42±0.87). The average ICU stay was also longer in the MA group (10.41±17.69 days) than in the NHI group (8.99±16.34 days).

Table 3 compares life-sustaining treatment use between NHI and MA decedents across the 0–30, 0–90, and 0–180 day periods before death. Overall, the utilization rates of most life-sustaining treatments—except for hemodialysis and vasopressors—were consistently higher among NHI decedents than among MA decedents. Specifically, NHI decedents had higher rates of CPR (13.0%, 13.6%, and 13.8% vs. 11.6%, 12.3%, and 12.5%), mechanical ventilation (14.2%, 16.3%, and 17.2% vs. 12.4%, 14.3%, and 15.1%), chemotherapy (8.2%, 15.6%, and 18.8% vs. 5.3%, 10.5%, and 12.9%), and transfusion (3.7%, 5.9%, and 6.7% vs. 2.0%, 3.3%, and 3.9%) across all observation windows (all

p<.001). In contrast, hemodialysis rates were higher in the MA group (4.3%, 5.0%, and 5.2% vs. 4.8%, 5.4%, and 5.6%), and vasopressor use was also higher among MA decedents (33.2%, 38.2%, and 40.3% vs. 34.0%, 38.8%, and 40.7%), except at 0–180 days, where the difference was not statistically significant.

4. Impact of Healthcare Insurance Type on the Utilization of Life-Sustaining Treatments during the 180 Days before Death

Table 4 shows the results of logistic regression analyses examining the association between health insurance type and use of life-sustaining treatments in the 180 days before death. The models were adjusted for age, sex, CCI score, place of death, and completion of advance directives or physician orders for life-sustaining treatment. Compared with NHI decedents, MA decedents were significantly less likely to receive mechanical ventilation (OR=0.93, 95% CI=0.90–0.96), chemotherapy (OR=0.62, 95% CI=0.60–0.64), transfusion (OR=0.58, 95% CI=0.55–0.61), and vasopressors (OR=0.97, 95% CI=0.95–0.99). Conversely, MA decedents were more likely to undergo hemodialysis (OR=1.06, 95% CI=1.01–1.11,

p=.017).

DISCUSSION

This study examined the impact of health insurance type on healthcare utilization, including life-sustaining treatments, during the last 180 days of life in older adults. The findings show that MA decedents experienced longer hospital and ICU stays but were significantly less likely than NHI decedents to receive most life-sustaining treatments, with the exceptions of CPR and hemodialysis. These results highlight the importance of targeted interventions to address socioeconomic disparities in EOL care by clarifying the underlying mechanisms and assessing the quality of care delivered.

In this study, the overall completion rate of advance directives and physician orders for life-sustaining treatment among all decedents was notably low. This may reflect the relatively short time since the implementation of the Life-Sustaining Treatment Decisions Act and the advanced age of the study population. Although national and professional initiatives have gradually increased completion rates [

19], the lower rates among MA decedents compared with NHI decedents remain concerning. This finding is consistent with previous studies showing that individuals from low-income households are less likely to participate in advance care planning and have limited access to or awareness of related resources [

20,

21]. Contributing factors include information asymmetry, limited health literacy, distrust of the healthcare system, and social barriers. In particular, MA beneficiaries often have lower education levels [

7,

22], less access to healthcare information, and more constrained healthcare-seeking behaviors [

22], which may hinder meaningful discussions with healthcare providers about future care preferences [

23]. Tailored educational and counseling programs, along with structured clinical guidance, are needed to promote advance care planning in vulnerable groups such as MA or Medicaid beneficiaries. These efforts are essential, as advance directives and physician orders for life-sustaining treatment form the foundation of care that reflects individual preferences and values.

Although MA decedents had fewer hospital admissions within 180 days before death, their hospitalizations and ICU stays were substantially longer than those of NHI decedents. This may be attributable to group characteristics, as MA decedents appeared to have greater disease severity, which could lead to more prolonged hospital and ICU stays. Similarly, Huang et al. [

24] reported that older decedents with cancer and lower SES experienced longer hospitalizations. These findings suggest that once admitted, MA beneficiaries may remain hospitalized longer due to delayed discharge planning [

25] or limited access to post-acute care resources, including home-based or long-term care services [

7,

26,

27]. Such limitations, often tied to socioeconomic disadvantage, may contribute to reliance on hospital-based care. However, some evidence contradicts this trend; for example, a Swedish study found that ICU patients with lower income, less education, and single-household status were more likely to forgo ICU treatment [

28]. Further investigation, including analysis of medical records, is needed to clarify these disparities.

When adjusting for age, sex, CCI score, place of death, and advance care planning, logistic regression showed that MA decedents were significantly less likely than NHI decedents to receive most life-sustaining treatments—except for CPR and hemodialysis—during the 180 days before death. This aligns with findings from a recent South Korean study [

29] showing that older adults with poor self-perceived financial and health status were less likely to prefer life-sustaining treatment at EOL. In particular, lower chemotherapy use among MA decedents may reflect financial barriers that limit access to oncology care and hinder timely initiation or continuation of treatment [

9]. Moreover, because MA beneficiaries often represent medically and socially vulnerable populations [

7], they may present with advanced disease, poor functional status, or delayed diagnoses, making them less suitable candidates for cancer-directed therapies [

30]. Providers may also hesitate to recommend chemotherapy to MA beneficiaries due to concerns about treatment adherence, follow-up capacity, or social support [

31]. However, these findings contrast with prior evidence suggesting that individuals with lower SES are more likely to receive aggressive EOL care, including life-sustaining treatments [

32], and are less likely to use hospice care [

9]. These inconsistencies underscore the need for further investigation into the mechanisms that reduce treatment utilization among MA beneficiaries. Importantly, our findings highlight the urgent need for targeted policies and clinical interventions to promote equitable, person-centered EOL care for socioeconomically disadvantaged populations, particularly those covered by MA.

Our logistic regression results also showed higher use of hemodialysis among MA decedents compared with NHI decedents. This pattern may be explained by the case payment system (flat-fee reimbursement scheme) for outpatient hemodialysis applied to MA beneficiaries since 2002 [

33]. Under this scheme, a fixed payment of approximately USD 100 per hemodialysis covers physician fees, dialysis materials and medications, and diagnostic tests [

33]. This substantially reduces the financial burden for MA beneficiaries and may encourage greater use of dialysis services [

34]. Further research is required to determine whether, and why, hemodialysis may be overutilized among MA beneficiaries at the EOL.

This study had several limitations. Because it relied on claims data, it lacked detailed clinical information such as patient preferences, functional status, the context of medical decision-making, and cause of death. In addition, because claims data exclude non-reimbursed services, it was not possible to account for out-of-pocket expenditures that may influence life-sustaining treatment use. This limitation restricts the ability to fully assess variations in utilization linked to patients’ financial burdens. Moreover, the analysis was confined to a single year, preventing evaluation of temporal trends. Future research should examine multi-year data to identify changes over time. Data on advance care planning were also limited, and the retrospective design precludes causal inference. Despite these limitations, this study provides valuable insights into disparities in EOL care by insurance type.

CONCLUSION

This study reveals significant disparities in EOL care by insurance type, showing that MA beneficiaries were less likely to receive aggressive treatments (except hemodialysis) and less likely to engage in advance care planning. These findings emphasize the need for multifaceted strategies to reduce inequities, strengthen decision-making support, and improve the quality of EOL care for medically and socially vulnerable populations. Future research should further investigate the drivers of these disparities and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed to improve EOL outcomes across socioeconomic groups.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Jeonghyun Cho has been the Editor-in-Chief of the Korean Journal of Adult Nursing since 2024. She was not involved the review process of this manuscript. Otherwise, there was no conflict of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and design acquisition - JC, HK, and SSK; data collection - NYK; analysis and interpretation of the data - JC, HK, NYK, JHB, and SSK; drafting and critical revision of the manuscript - JC, HK, SSK, JHB, and NYK.

-

FUNDING

This work was supported by a grant from research year of Inje University in 2022 (20220023).

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

None.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data are not publicly available due to institutional regulations and please contact the corresponding author for data availability.

Figure 1.Flow chart of cohort selection.

Table 1.General Characteristics of the Participants (N=286,319)

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

n (%) or mean±SD |

χ2/t |

p

|

|

NHI (n=247,935) |

MA (n=38,384) |

|

Sex |

Male |

125,972 (50.8) |

17,113 (44.6) |

515.17 |

<.001 |

|

Female |

121,963 (49.2) |

21,271 (55.4) |

|

|

|

Age (year) |

|

82.86±8.24 |

81.66±9.20 |

–24.09 |

<.001 |

|

65–74 |

44,273 (17.9) |

9,852 (25.7) |

1,323.11 |

<.001 |

|

75–84 |

90,098 (36.3) |

12,554 (32.7) |

|

|

|

85 or older |

113,564 (45.8) |

15,978 (41.6) |

|

|

|

Size of residential area |

Large |

92,423 (37.3) |

16,159 (42.1) |

408.48 |

<.001 |

|

Medium |

115,654 (46.6) |

17,168 (44.7) |

|

|

|

Small |

39,858 (16.1) |

5,057 (13.2) |

|

|

|

No. of chronic diseases |

|

2.12±1.17 |

2.12±1.21 |

–0.82 |

.411 |

|

0 |

10,309 (4.2) |

1,558 (4.1) |

69.15 |

<.001 |

|

1 |

72,900 (29.4) |

11,994 (31.2) |

|

|

|

2 |

81,758 (33.0) |

11,995 (31.3) |

|

|

|

3 or more |

82,968 (33.5) |

12,837 (33.4) |

|

|

|

CCI score |

|

0.32±0.87 |

0.33±0.88 |

2.15 |

.032 |

|

0 |

214,655 (86.6) |

33,073 (86.2) |

5.18 |

.159 |

|

1 |

6,844 (2.8) |

1,094 (2.9) |

|

|

|

2 |

6,257 (2.5) |

982 (2.6) |

|

|

|

3 or more |

20,179 (8.1) |

3,235 (8.4) |

|

|

|

Place of death |

Tertiary hospital |

41,969 (16.9) |

4,503 (11.7) |

1,798.69 |

<.001 |

|

General hospital |

75,357 (30.4) |

10,977(28.6) |

|

|

|

Long-term care hospital |

81,711 (33.0) |

16,597 (43.2) |

|

|

|

Others |

48,898 (19.7) |

6,307 (16.4) |

|

|

|

Advance directive |

Yes |

7,011 (2.8) |

421 (1.1) |

393.89 |

<.001 |

|

No |

240,924 (97.2) |

37,963 (98.9) |

|

|

|

POLST |

Yes |

2,425 (1.0) |

335 (0.9) |

3.86 |

.049 |

|

No |

245,510 (99.0) |

38,049 (99.1) |

|

|

Table 2.Number of Admissions and Lengths of Stays in Hospital and ICU for 180 Days before Death by Health Insurance Type (N=286,319)

|

Variables |

Mean±SD |

t |

p

|

|

NHI (n=247,935) |

MA (n=38,384) |

|

Number of hospital admissions |

6.08±5.44 |

5.25±4.57 |

–51.91 |

<.001 |

|

Length of hospitalization (day) |

30.85±68.45 |

45.86±88.77 |

51.09 |

<.001 |

|

Number of ICU admissions |

1.42±0.87 |

1.47±0.93 |

4.86 |

<.001 |

|

Length of ICU stay (day) |

8.99±16.34 |

10.41±17.69 |

8.02 |

<.001 |

Table 3.Use of Life-Sustaining Treatment for 180 Days before Death by Health Insurance Scheme

|

Categories |

|

0–30 days |

0–90 days |

0–180 days |

|

n (%) |

χ2

|

p

|

n (%) |

χ2

|

p

|

n (%) |

χ2

|

p

|

|

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

NHI |

32,118 (13.0) |

55.04 |

<.001 |

33,796 (13.6) |

49.63 |

<.001 |

34,233 (13.8) |

45.76 |

<.001 |

|

MA |

4,451 (11.6) |

|

|

4,726 (12.3) |

|

|

4,811 (12.5) |

|

|

|

Mechanical ventilation |

NHI |

35,262 (14.2) |

92.49 |

<.001 |

40,445 (16.3) |

98.91 |

<.001 |

42,574 (17.2) |

99.53 |

<.001 |

|

MA |

4,757 (12.4) |

|

|

5,493 (14.3) |

|

|

5,804 (15.1) |

|

|

|

Hemodialysis |

NHI |

10,669 (4.3) |

18.54 |

<.001 |

12,376 (5.0) |

14.24 |

<.001 |

12,791 (5.2) |

14.09 |

<.001 |

|

MA |

1,837 (4.8) |

|

|

2,090 (5.4) |

|

|

2,156 (5.6) |

|

|

|

Chemotherapy |

NHI |

20,215 (8.2) |

371.51 |

<.001 |

38,584 (15.6) |

677.51 |

<.001 |

46,504 (18.8) |

766.04 |

<.001 |

|

MA |

2,043 (5.3) |

|

|

4,023 (10.5) |

|

|

4,962 (12.9) |

|

|

|

Transfusion |

NHI |

9,144 (3.7) |

299.22 |

<.001 |

14,517 (5.9) |

405.06 |

<.001 |

16,703 (6.7) |

437.56 |

<.001 |

|

MA |

758 (2.0) |

|

|

1,280 (3.3) |

|

|

1,511 (3.9) |

|

|

|

Vasopressors |

NHI |

82,372 (33.2) |

9.36 |

.002 |

94,702 (38.2) |

4.91 |

.027 |

99,848 (40.3) |

2.52 |

.112 |

|

MA |

13,056 (34.0) |

|

|

14,888 (38.8) |

|

|

15,622 (40.7) |

|

|

Table 4.Impact of Healthcare Insurance Type on the Use of Life-Sustaining Treatments for 180 Days before Death

|

Dependent variables |

Odds ratios |

95% CI |

p

|

|

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation |

0.97 |

0.94–1.01 |

.130 |

|

Mechanical ventilation |

0.93 |

0.90–0.96 |

<.001 |

|

Hemodialysis |

1.06 |

1.01–1.11 |

.017 |

|

Chemotherapy |

0.62 |

0.60–0.64 |

<.001 |

|

Transfusion |

0.58 |

0.55–0.61 |

<.001 |

|

Vasopressors |

0.97 |

0.95–0.99 |

.006 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Bowers SP, Chin M, O'Riordan M, Carduff E. The end of life experiences of people living with socio-economic deprivation in the developed world: an integrative review. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21(1):193. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-01080-6

- 2. Jo M, Lee Y, Kim T. Medical care costs at the end of life among older adults with cancer: a national health insurance data-based cohort study. BMC Palliat Care. 2023;22(1):76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-023-01197-2

- 3. Yong J, Yang O. Does socioeconomic status affect hospital utilization and health outcomes of chronic disease patients? Eur J Health Econ. 2021;22(2):329-39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10198-020-01255-z

- 4. Kim S, Sohn M, Kim G, Choi M. Impact of chronic elderly patients with private health insurance on medical use. Health Soc Welfare Rev. 2020;40(3):152-77. https://doi.org/10.15709/hswr.2020.40.3.152

- 5. Sitima G, Galhardo-Branco C, Reis-Pina P. Equity of access to palliative care: a scoping review. Int J Equity Health. 2024;23(1):248. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-024-02321-1

- 6. National Health Insurance Services. 2023 National Health Insurance Statistical Yearbook. National Health Insurance Services Report. Wonju: National Health Insurance Services; 2024 November. Report No.: 11-B50928-000001-10.

- 7. Kim J, Park SH, Lee H, Lee SK, Kim J, Kim S, et al. Identifying potential medical aid beneficiaries using machine learning: a Korean Nationwide cohort study. Int J Med Inform. 2025;195:105775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2024.105775

- 8. Vestergaard AH, Christiansen CF, Neergaard MA, Valentin JB, Johnsen SP. Socioeconomic disparity trends in end-of-life care for cancer and non-cancer patients: are we closing the gap? Clin Epidemiol. 2022;14:653-64. https://doi.org/10.2147/clep.S362170

- 9. Lai YJ, Chen YY, Ko MC, Chou YS, Huang LY, Chen YT, et al. Low socioeconomic status associated with lower utilization of hospice care services during end-of-life treatment in patients with cancer: a population-based cohort study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2020;60(2):309-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.03.015

- 10. Johnston EE, Bogetz J, Saynina O, Chamberlain LJ, Bhatia S, Sanders L. Disparities in inpatient intensity of end-of-life care for complex chronic conditions. Pediatrics. 2019;143(5):e20182228. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-2228

- 11. Davies JM, Sleeman KE, Leniz J, Wilson R, Higginson IJ, Verne J, et al. Socioeconomic position and use of healthcare in the last year of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2019;16(4):e1002782. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002782

- 12. Bronner KK, Goodman DC. End-of-life cohorts from the Dartmouth Institute: risk adjustment across health care markets, the relative efficiency of chronic illness utilization, and patient experiences near the end of life. Res Health Serv Reg. 2024;3(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43999-024-00039-9

- 13. Chen M, Yang L, Yu H, Yu H, Wang S, Tian L, et al. Early palliative care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized controlled trial in Southwest China. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2022;39(11):1304-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/10499091211072502

- 14. Moon F, McDermott F, Kissane D. Systematic review for the quality of end-of-life care for patients with dementia in the hospital setting. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(12):1572-83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909118776985

- 15. Hwang J, Shen J, Kim SJ, Chun SY, Kioka M, Sheraz F, et al. Ten-year trends of utilization of palliative care services and life-sustaining treatments and hospital costs associated with patients with terminally ill lung cancer in the United States from 2005 to 2014. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2019;36(12):1105-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909119852082

- 16. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e296. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0040296

- 17. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Act on Hospice and Palliative Care and Decisions on Life-Sustaining Treatment for Patients at the End of Life, Act No. 19466 [Internet]. Sejong: Korea Legislation Research Institute; 2023 [cited 2025 April 1]. Available from: https://elaw.klri.re.kr/kor_service/lawView.do?hseq=68003&lang=KOR

- 18. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83

- 19. National Agency for Management of Life-Sustaining Treatment. Understanding the life-sustaining treatment decision system through statistics [Internet]. Seoul: National Agency for Management of Life-Sustaining Treatment; 2025 [cited 2025 August 6]. Available from: https://www.lst.go.kr/comm/cardDetail.do?bno=5321&brdctsclsno=

- 20. Kimpel CC, Frechman E, Chavez L, Maxwell CA. Essential advance care planning intervention features in low-income communities: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2025;69(1):e46-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2024.09.018

- 21. Nouri S, Lyles CR, Rubinsky AD, Patel K, Desai R, Fields J, et al. Evaluation of neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics and advance care planning among older adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2029063. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29063

- 22. Cho J, Jeong K, Kim S, Kim H. Exploring the healthcare seeking behavior of medical aid beneficiaries who overutilize healthcare services: a qualitative descriptive study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(14):2485. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16142485

- 23. Kim S, Lim A, Jang H, Jeon M. Life-sustaining treatment decision in palliative care based on electronic health records analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(1-2):163-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16206

- 24. Huang CY, Hung YT, Chang CM, Juang SY, Lee CC. The association between individual income and aggressive end-of-life treatment in older cancer decedents in Taiwan. PLoS One. 2015;10(1):e0116913. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0116913

- 25. Everall AC, Guilcher SJ, Cadel L, Asif M, Li J, Kuluski K. Patient and caregiver experience with delayed discharge from a hospital setting: a scoping review. Health Expect. 2019;22(5):863-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12916

- 26. Coogan A, Kimpel C, Jones AC, Barroso J, Frechman E, Maxwell CA. Perspectives on aging and end of life among lower socioeconomic status (SES) older adults. J Appl Gerontol. 2022;41(6):1595-603. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648221081482

- 27. Lera J, Pascual-Saez M, Cantarero-Prieto D. Socioeconomic inequality in the use of long-term care among european older adults: an empirical approach using the SHARE survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;18(1):20. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010020

- 28. Strandberg G, Lipcsey M. Association of socioeconomic and demographic factors with limitations of life sustaining treatment in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2023;49(10):1249-50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-023-07177-7

- 29. Hwang YH, Jun HJ, Park HR. Factors influencing intention to use life-sustaining treatment of community-dwelling older adults using the 2020 national survey of older Koreans: secondary analysis research. J Korean Gerontol Nurs. 2022;24(4):424-32. https://doi.org/10.17079/jkgn.2022.24.4.424

- 30. Vaz J, Hagstrom H, Eilard MS, Rizell M, Stromberg U. Socioeconomic inequalities in diagnostics, care and survival outcomes for hepatocellular carcinoma in Sweden: a nationwide cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2025;52:101273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2025.101273

- 31. Knotts C, Van Horn A, Orminski K, Thompson S, Minor J, Elmore M, et al. Clinical and socioeconomic factors that predict non-completion of adjuvant chemotherapy for colorectal cancer in a rural cancer center. Am Surg. 2023;89(5):1592-7. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031348211054708

- 32. Haripottawekul A, Stipanovich A, Uriarte SA, Persad-Paisley EM, Furie KL, Reznik ME, et al. The impact of socioeconomic status on decision on withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2025;42(3):1054-63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-024-02197-7

- 33. Ministry of Health and Welfare. Guideline for medical-aid program in 2025 [Internet]. Sejong: Ministry of Health and Welfare; 2025 [cited 2025 August 12]. Available from: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10402000000&bid=0009&act=view&list_no=1484212&tag=&nPage=1

- 34. Kim JW, Ye RM, Kim MH, Lee DY. Changes in pattern of the medical care use of outpatient with mental disorder according to medical coverage types and medical payment system. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 2022;61(3):150-5. https://doi.org/10.4306/jknpa.2022.61.3.150