Abstract

-

Purpose

This study aimed to clarify the concept of nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration by employing Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis, which reflects both sociocultural and temporal dimensions.

-

Methods

A six-step concept analysis was conducted following Rodgers’ methodology. A systematic literature review was performed using PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, and Google Scholar, yielding 35 relevant studies published between 2000 and 2025. Data extraction followed the Joanna Briggs Institute template, and quality was appraised using the STROBE checklist.

-

Results

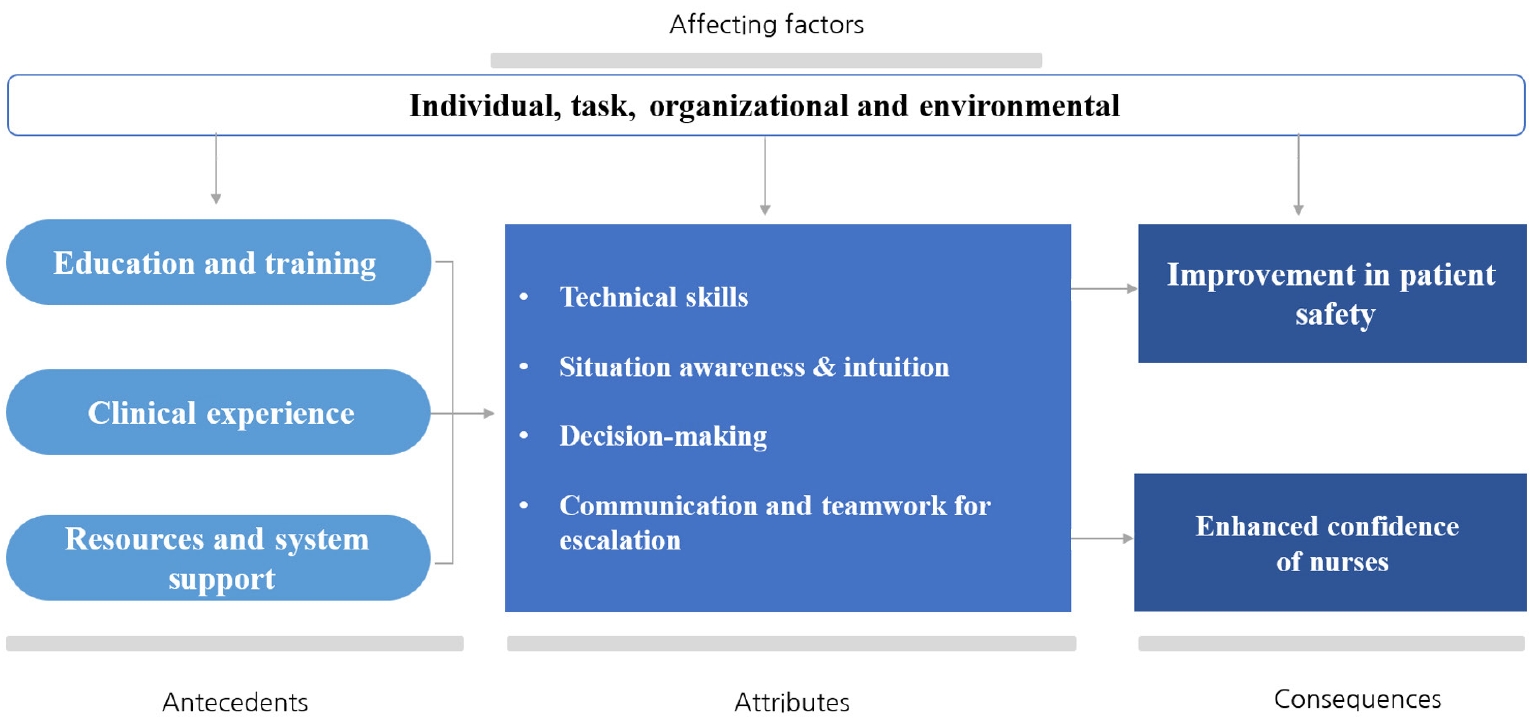

Four key attributes of nursing competence were identified: technical skills in patient monitoring, situational awareness and clinical intuition, decision-making regarding escalation of care, and communication and teamwork to ensure timely intervention. Antecedents included formal education, clinical experience, and institutional support. Consequences encompassed enhanced patient safety, increased nurse confidence, and greater professional autonomy. The concept was demonstrated to be dynamic and influenced by healthcare policies, such as the implementation of rapid response systems.

-

Conclusion

Nursing competence in managing clinical deterioration is a multidimensional and evolving concept that is essential for patient safety. Clarification of this concept can inform the development of assessment tools and simulation-based education. Further research should explore its application across diverse healthcare contexts and address challenges related to escalation of care.

-

Key Words: Clinical competence; Clinical deterioration; Coping skill; Concept formation; Analysis

INTRODUCTION

In-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) remains a major concern in acute care settings, with incidence rates in the United States ranging from 0.8 to 4.6 cases per 1,000 hospital admissions [

1]. Each year, approximately 300,000 patients experience IHCA, yet survival rates remain low, at around 25% [

2]. Previous research has demonstrated that in nearly 80% of IHCA cases, abnormal changes in vital signs—such as tachycardia, tachypnea, or hypotension—were observed 6 to 24 hours prior to arrest [

3]. These physiological changes are recognized as warning signs of clinical deterioration and underscore the crucial importance of early detection and timely intervention. Nurses, as frontline healthcare providers, play a pivotal role in identifying these signs, interpreting clinical assessments, and initiating appropriate escalation of care [

4].

The term “clinical” derives from the Greek word “

klinein”, meaning “to lean” or “bed”, which signifies bedside care. “Deterioration” comes from the Latin “

deteriorare”, meaning “to worsen”. In clinical practice, deterioration refers to a gradual decline in a patient’s physiological state, often preceding critical events such as cardiac arrest or multiple organ failure [

5,

6]. The concept of “nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration” integrates the notion of coping (i.e., effectively responding to emergencies) with competence, which encompasses the knowledge, skills, and judgment required to fulfill a professional role. In high-risk clinical settings, this competence reflects a nurse’s capacity to act expertly under pressure [

7].

Internationally, health systems have responded to the need for early detection by introducing structured systems and policies. In the United States, the “100,000 Lives Campaign” launched in 2004 established rapid response teams (RRTs) as a standard for patient safety [

8]. Similarly, Australia’s National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards and the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) have developed comprehensive guidelines for recognizing and managing clinical deterioration. These include the use of early warning scores (EWS), interprofessional communication strategies, and training protocols [

9,

10]. Such measures have contributed to the standardization of roles and competencies in acute care nursing. Over the past two decades, the required competencies for nurses in these countries have evolved from basic physiological monitoring to more advanced skills, including clinical reasoning, interprofessional teamwork, and leadership in escalation processes.

In contrast, Korea only recently institutionalized the rapid response system (RRS) in 2019 as part of the National Patient Safety Comprehensive Plan [

11], reflecting a delayed integration of systemic approaches to clinical deterioration [

12]. Although this has led to improvements in policy and practice, ongoing challenges include limited nurse autonomy, delayed escalation, and underutilization of early warning systems [

13]. Furthermore, despite its clinical significance, the concept of ‘nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration’ has not been clearly defined or formalized within Korean nursing. Instead, related terms such as “emergency care” [

14] and “emergency nursing competency” [

15] have been used variably, often without explicit recognition of the evolving roles of nurses in complex and dynamic deterioration scenarios.

Given these discrepancies, the current study aimed to bridge the gap by clarifying the concept of nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration using Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis [

16]. This approach highlights the dynamic nature of concepts, recognizing that they are shaped by historical, sociocultural, and organizational factors. By employing this method, the study aims to delineate the essential attributes, antecedents, and consequences of the concept, and to trace its evolution over time, especially in light of changes in healthcare technologies, patient acuity, system structures, and the expanding roles of nurses in both Western and Korean contexts. This analysis will contribute to greater conceptual clarity and support the development of contextually relevant educational, clinical, and policy strategies within the Korean healthcare system.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This study applied Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis method, which emphasizes the dynamic and context-dependent nature of concepts, recognizing that they evolve over time in response to changes in sociocultural, technological, and organizational environments [

16]. This approach is particularly well-suited to exploring complex and multifaceted concepts such as nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration, which have undergone significant transformation alongside developments in healthcare systems and professional roles over the past two decades.

To strengthen the rigor of the analysis, the study included a deliberate exploration of the historical and cultural evolution of the concept, as recommended by Rodgers and Knafl [

16]. The analysis focused on tracing how the competencies required for nurses responding to clinical deterioration have evolved over the past 25 years, in parallel with changes in healthcare systems, patient acuity, medical technology, and safety policies.

Given that in Korea, research and systemic integration regarding this concept remain in their early stages and are still largely insufficient, this study primarily relied on the analysis of international studies. The purpose was to provide a clarified and systematic understanding of the concept based on global evidence, offering foundational knowledge that can be adapted and applied appropriately within the Korean healthcare context.

2. Researcher Preparation

The principal investigator is a registered nurse with over 10 years of clinical experience in intensive care units, as well as experience as an RRT nurse in tertiary hospitals. The researcher conducted an extensive review of international literature from countries where clinical deterioration management systems are well established, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. This global perspective was integrated into the analysis to ensure that the conceptual clarification reflects universal nursing competencies, while also providing a foundation for future adaptation and application in Korea’s distinct healthcare environment.

In conducting Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis, it is essential for researchers to maintain methodological rigor and reflexivity. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for selecting relevant literature must be clearly defined to ensure the credibility of the sample. To ensure the validity of the categorization process, one researcher (U.S.) and a research assistant (S.P.) independently classified the variables based on predefined criteria. They then engaged in iterative discussions to address and resolve any inconsistencies. When discrepancies could not be resolved through consensus, the responsible author reviewed the cases and made the final decision. This collaborative and structured approach enhanced the consistency and reliability of the classification framework.

Furthermore, it is crucial to avoid allowing preexisting understandings of the concept to bias the literature search or data interpretation [

16]. As concept analysis is an iterative and interpretive process, all decisions regarding literature selection and conceptual interpretation should be systematically documented to enhance the study’s trustworthiness and transparency. This reflective documentation process reinforces the reliability of the research and demonstrates the researcher’s preparedness and awareness of potential bias.

The six-stage process of Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis was systematically applied:

1) Identification of the concept and related terms

The core concept of 'nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration’ was identified, along with surrogate and related terms frequently found in the literature, such as “nursing ability”, “nursing competence”, and “nurse’s role”. Special attention was paid to examining how these terms have been used and understood across different countries and time periods.

2) Selection of the literature

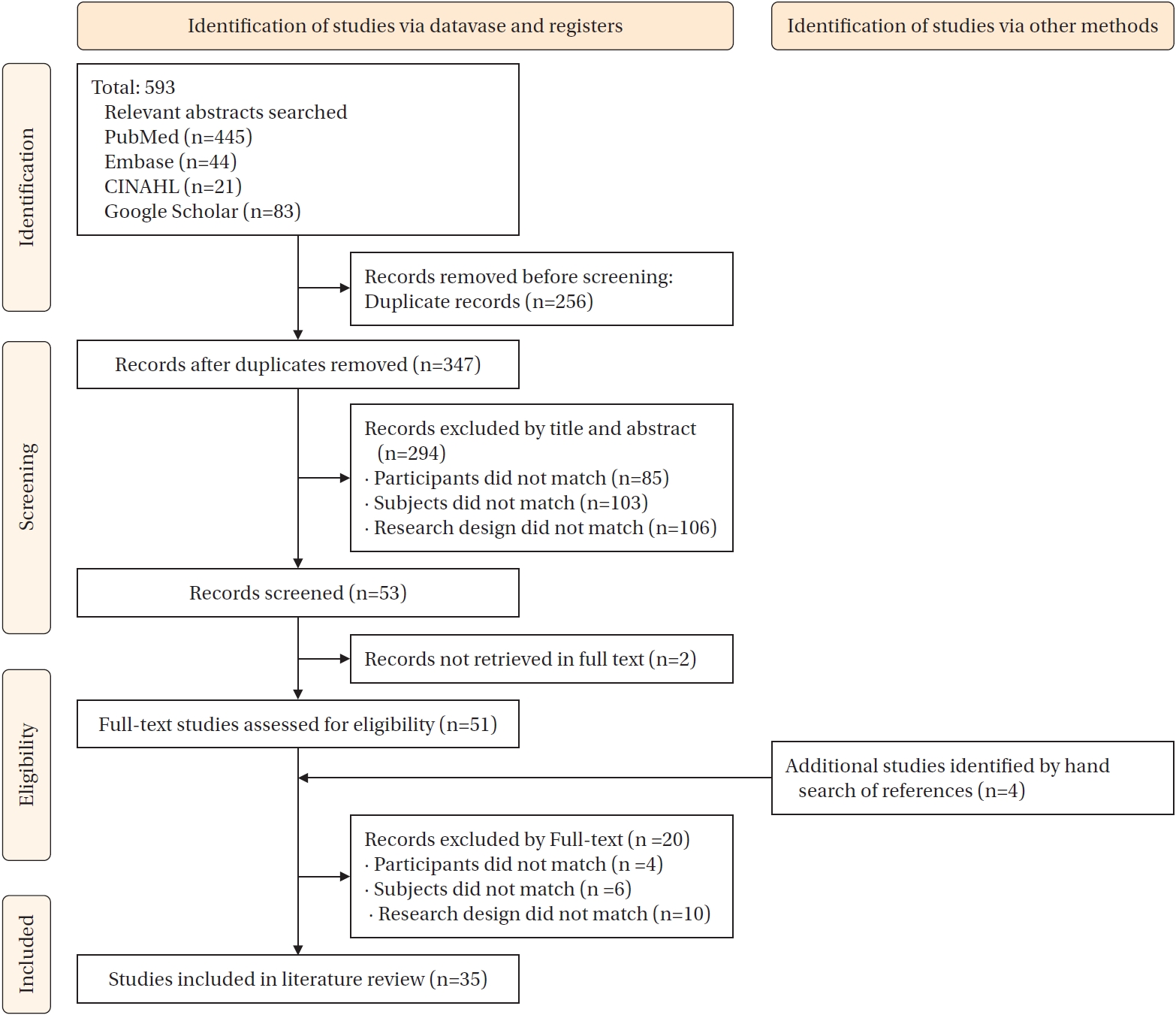

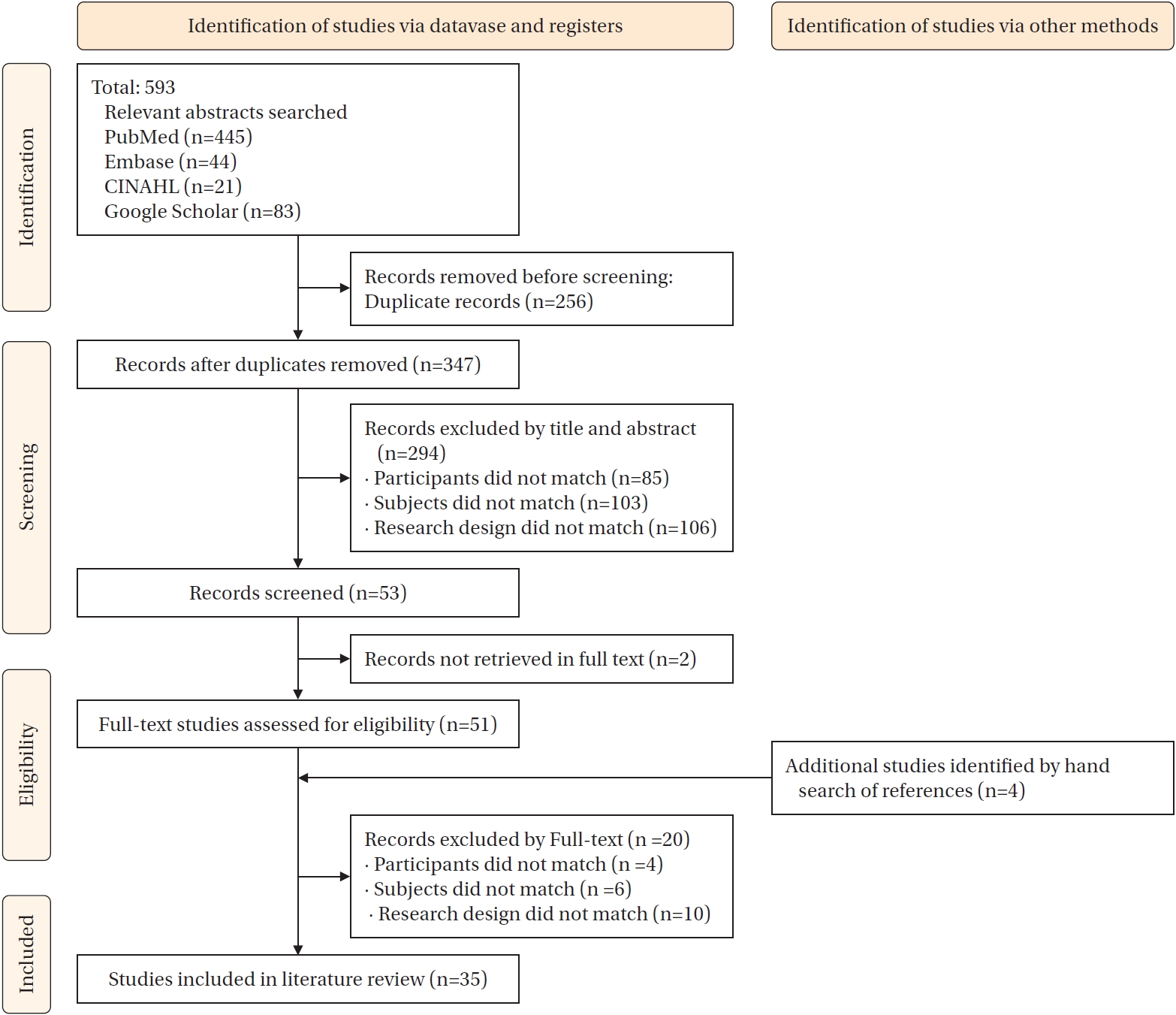

A comprehensive literature search was conducted using keywords including “clinical deterioration”, “patient deterioration”, “nursing competence”, “nursing ability”, “nursing capacity”, and “nursing role”. Four databases (PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, and Google Scholar) were searched for literature published from January 2000 to March 2025, in order to capture the historical development of the concept over the past 25 years. Additional studies identified by hand search of references.

3) Data collection

A total of 593 articles were initially retrieved. After screening according to predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, 35 articles were selected for the final analysis (

Table 1,

Figure 1,

Appendix 1). Data extraction was conducted using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) data extraction template and the STROBE checklist [

17], ensuring methodological rigor throughout the process.

4) Data analysis

The selected articles were categorized into three time periods to analyze how understandings and expectations of nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration have changed over time. Attributes, antecedents, and consequences were examined in relation to shifts in healthcare systems, patient safety policies, technological advancements, and the expanding roles of nurses within multidisciplinary teams. Cross-national comparisons were also performed to identify contextual similarities and differences. Through this process, the core components that consistently define nursing competence were identified. The synthesis of these components is summarized and systematically organized, presenting derived elements, key references, and the analytical process for attributes, antecedents, affecting factors, and consequences (

Table 2).

5) Comparison with related concepts and clarification

The identified conceptual elements were compared with related concepts commonly used in Korea, assessing areas of overlap, distinction, and those requiring further clarification. This process was designed to ensure that the clarified concept is relevant for the Korean nursing context, while remaining consistent with international standards.

6) Development of conceptual framework and hypotheses

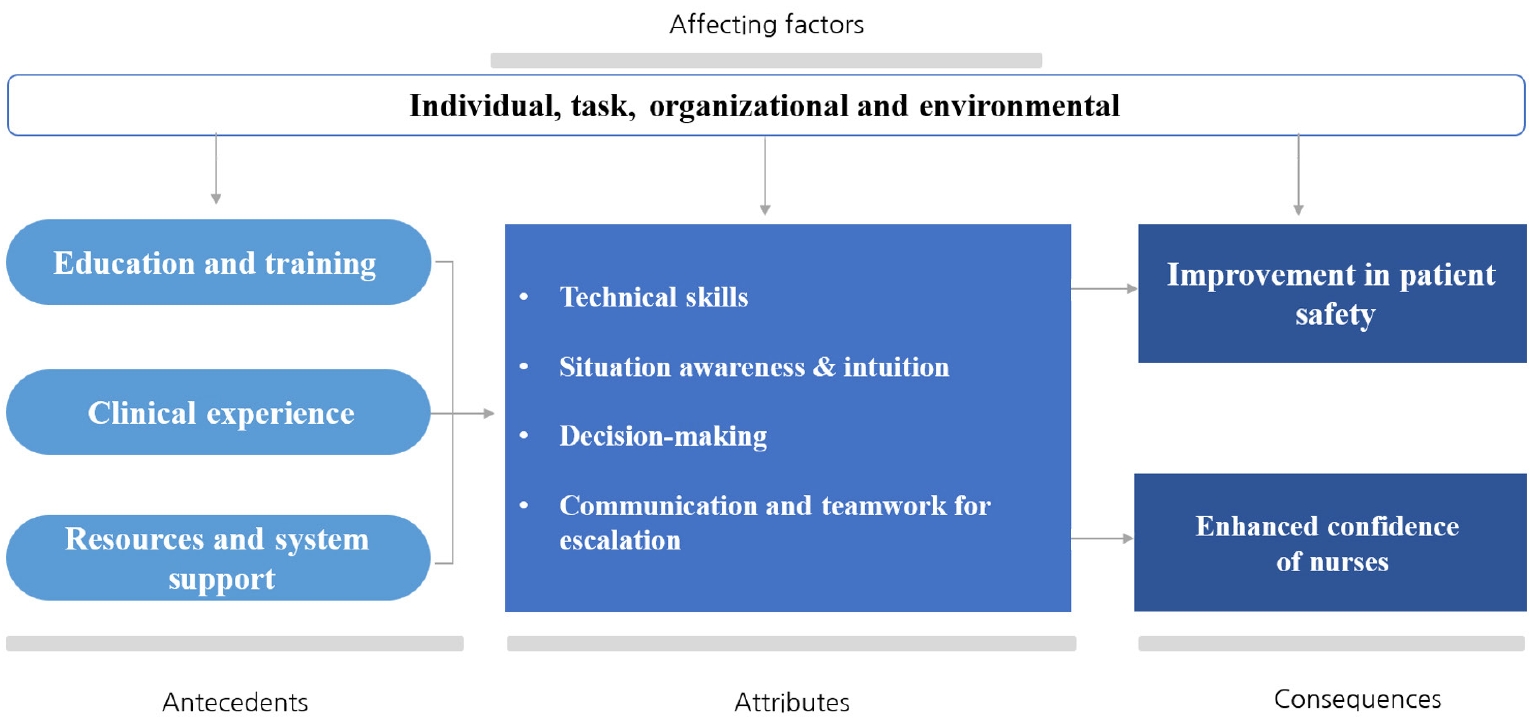

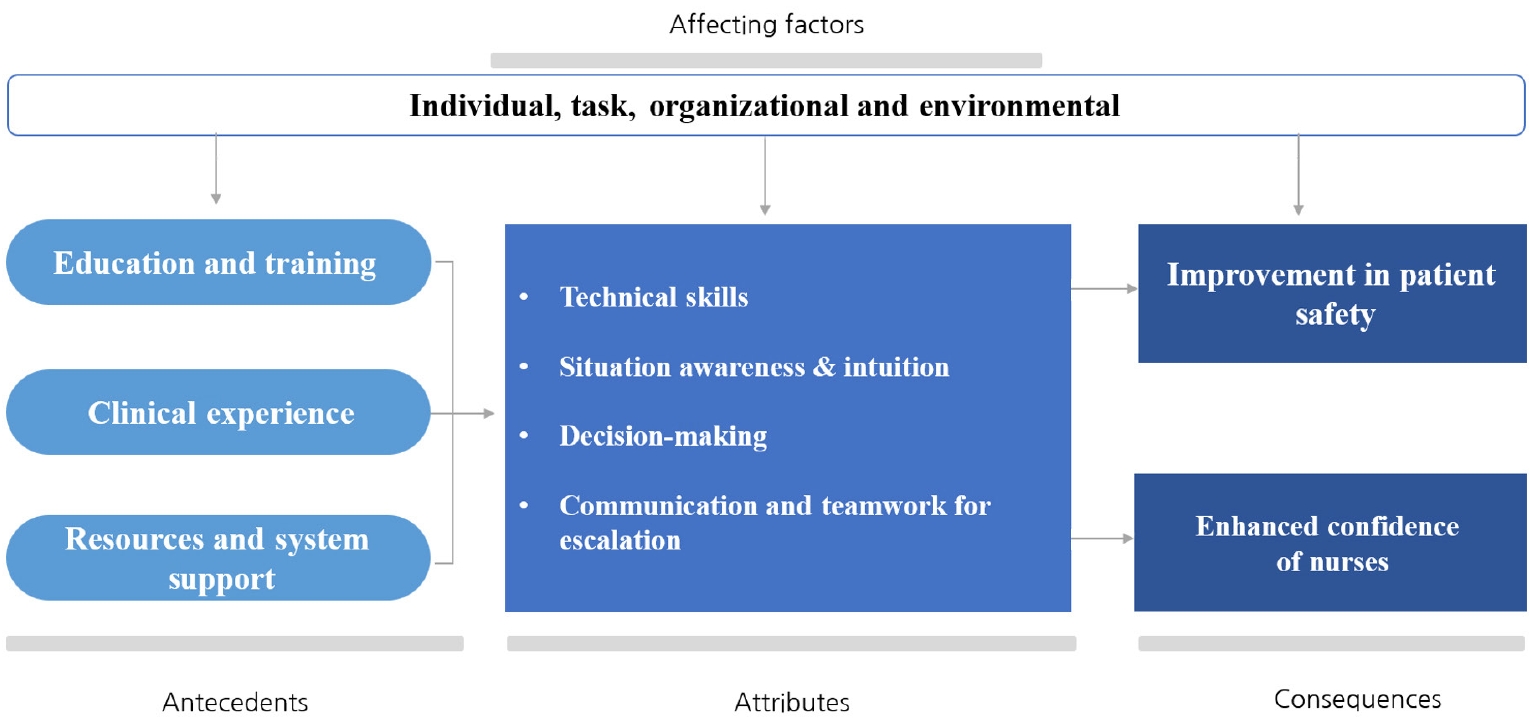

A conceptual model integrating the identified attributes, antecedents, and consequences was developed (

Figure 2). Based on the evolutionary analysis, hypotheses were formulated regarding the relationships among these components and their anticipated impact on nursing practice outcomes. While grounded in international research, the resulting model was structured to provide both theoretical rigor and practical applicability, serving as a reference for Korean healthcare settings aiming to enhance nursing competence in clinical deterioration management.

RESULTS

1. Temporal Evolution of the Concept

The selected studies were organized into three periods for analysis: 2000–2010 (emerging systems), 2011–2020 (system establishment and expansion), and 2021–2025 (competence refinement and proactive nursing leadership). The conceptual elements—attributes, antecedents, and consequences—were examined both for their content and for how they evolved over time, considering the influence of healthcare policy, technological advancements, and changing professional expectations. For this study, the 35 selected articles were systematically categorized into these three distinct timeframes to allow for an in-depth temporal analysis of the evolution of nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration.

During 2000–2010 (emerging systems), the literature primarily focused on basic clinical skills, including vital signs monitoring, fundamental patient assessment (ABCD [Airway, Breathing, Circulation, Disability] approach), and early recognition of physiological changes [A4,A18,A28]. Nurses’ roles were largely limited to data collection and reporting, with minimal participation in decision-making or care escalation. The emphasis was on strengthening individual clinical skills to enable early detection of deterioration, mirroring the initial phase of structured patient safety system implementation in Western countries.

In the 2011–2020 (system establishment and expansion) period, research reflected a shift toward more systematized responses to patient deterioration, marked by the global proliferation of EWS and RRS [A2,A5,A6,A8-14,A20-22,A24,A26,A29-31,A33]. The nurse’s role expanded from that of an observer to an active participant in patient safety, requiring competencies in situational awareness, interdisciplinary communication, and the use of standardized escalation protocols [A4,A8,A11,A14,A20,A24,A31]. This period also involved a growing emphasis on simulation-based training, team leadership, and decision-support systems to improve nursing responses [A26,A30,A31].

Finally, the 2021–2025 period (competence refinement and proactive nursing leadership) was characterized by a proactive, leadership-centered approach to clinical deterioration management [A1,A3,A7,A15-17,A19,A23,A25,A27,A32,A34,A35]. Nurses were expected to take advocacy roles, lead team-based interventions, and utilize advanced technologies—such as AI-driven patient monitoring systems—to anticipate deterioration and act with greater autonomy [A19,A21,A24,A25,A34]. The concept of nursing competence became increasingly integrative, encompassing technical skills, clinical judgment, teamwork, decision-making, and proactive leadership. This trend reflects the global movement toward empowering nurses as central agents in transforming patient safety culture.

2. Cross-National Comparisons

To further increase the contextual relevance of the analysis, cross-national comparisons were conducted, focusing on studies from the United States [A2,A10,A16,A17,A18,A29,A30,A33], the United Kingdom [A4,A11,A13,A15,A28,A35], and Australia [A8,A12,A14,A20,A26,A31], which represented the majority of the selected literature.

This comparison highlighted both similarities and differences in how the concept of nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration was developed and operationalized in different countries. Common themes included the progressive shift from an emphasis on technical skills toward the development of decision-making, leadership, and interdisciplinary communication competencies—largely propelled by the institutionalization of EWS and RRS during the 2010s.

However, notable country-specific differences also emerged. For example, studies from the United Kingdom emphasized early recognition through structured tools and team-based communication protocols, such as the Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation (SBAR) framework. In contrast, Australian studies frequently focused on simulation-based training and nurse-led escalation behaviors. U.S. studies were more likely to address the integration of advanced technologies and advocated for nurse autonomy in activating RRS without prior physician approval.

These cross-national insights provided a nuanced understanding of how sociocultural, policy, and systemic factors have shaped the evolution of the concept, offering guidance for its adaptation in contexts like Korea, where such systems remain in early stages of implementation.

3. Conceptual Derivation

Nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration refers to the ability to flexibly and continuously manage and resolve problems in situations characterized by hemodynamic instability due to diminished physiological compensation, accompanied by subjective or objective signs [

6]. Coping with clinical deterioration requires the recognition of trends in a patient’s condition over time and the ability to interpret them—a process often described as complex and demanding. In clinical practice, nurses are expected to integrate their formal education, accumulated experience, and intuitive judgment. This competence involves the ability to collect objective data based on nursing knowledge, recognize signs of physiological compromise, interpret and understand the patient’s condition, and make decisions that facilitate appropriate escalation of care [A5,A34].

In this study, the concept of nursing competence in responding to clinical deterioration is defined as a series of professional abilities to promptly recognize early signs of patient decline, make accurate clinical judgments, and initiate escalation of treatment as needed. This competence encompasses technical assessment skills, situational awareness and clinical intuition, clinical decision-making, and effective interdisciplinary communication and teamwork. It can be strengthened through repeated clinical exposure, structured education, and the implementation of supportive systems such as the EWS and RRS. Ultimately, this competence contributes to improved patient safety, enhanced nurse confidence, and the advancement of a collaborative and responsive organizational culture in healthcare settings (

Figure 2).

1) Surrogate and related terms

In the general nursing literature, terms such as “nursing performance,” “nursing practice,” and “clinical competencies” are often used interchangeably. Similarly, within the context of clinical deterioration, related terms—including “nursing performance,” “nursing ability,” “nursing capacity,” and “nursing role”—frequently overlap conceptually with nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration [A1,A34].

2) Affecting factors

This study identified factors influencing nursing competence in responding to clinical deterioration—encompassing antecedents, attributes, and consequences—across four levels: individual [A3,A16,A34], task [A8,A30,A33], organizational [A5,A21,A23,A28], and environmental [A35]. These multi-level influences reflect the complex interplay among personal capabilities, role-related demands, institutional structures, and broader clinical settings.

3) Antecedents

Antecedents refer to the events or conditions that must occur before the concept can manifest [

16]. In this context, the question “What must precede the demonstration of nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration?” was repeatedly considered. The primary antecedents identified in this study are as follows:

(1) Education and training

Education and training focused on clinical deterioration are essential. Nurses must be equipped with both theoretical knowledge and practical skills relevant to emergency situations. This includes instruction on the use of RRSs, EWS, clinical judgment, communication, and interprofessional collaboration [A15]. Ongoing on-site education and immersive simulation-based training that realistically replicates clinical deterioration scenarios have been shown to enhance nurses’ self-efficacy and confidence [A25]. Integrating diverse educational strategies and materials into structured programs is emphasized as a way to strengthen nurses’ response capabilities [A22]. Furthermore, just-in-time training methods tailored to real-time clinical contexts promote self-directed learning and foster the acquisition of situational knowledge and skills [A31].

(2) Clinical experience

Repeated clinical exposure plays a critical role in building situational awareness and decision-making ability. Nurses’ accumulated experience fosters intuitive reasoning and pattern recognition in similar clinical situations [

17]. This experiential knowledge enables early identification of deviations from a patient’s baseline and promotes intuitive responses to deterioration. Previous studies have shown that peer support during care escalation is highly valued, and the influence of experienced senior nurses is particularly significant [A15,A25].

(3) Resources and system support

Adequate access to resources and system support is essential for nurses to fully demonstrate their competencies. The availability of tools such as the EWS and RRS empowers nurses, supports clinical decision-making, and boosts confidence in care escalation [A3]. These systems also facilitate effective communication [A3,A22]. Furthermore, the use of EWS reinforces the importance of vital signs and increases nurses’ vigilance in recognizing clinical deterioration [A22].

4) Attributes

Conceptual attributes are the essential characteristics that define and distinguish a concept. Identifying these attributes makes it possible to generalize the concept to all related cases. The process of attribute definition is central to concept analysis. In this study, the attributes of nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration were specified as follows:

(1) Technical skills

Among the various competencies required of nurses, the measurement of vital signs—a fundamental aspect of patient assessment—is crucial in the early identification of patients at risk for clinical deterioration. Timely detection allows for sufficient intervention to prevent failure to rescue [A29]. It is necessary to establish evidence-based guidelines for the frequency of vital sign monitoring, methods of physical assessment for patient safety, and appropriate clinical responses to deterioration [A35]. Instruments used to assess nurses’ ability to recognize and respond to clinical deterioration typically include elements such as gathering and analyzing disease-related information [A34]. The primary assessment (ABCD) is used to evaluate airway patency, respiratory and circulatory function, and neurological status, prioritizing treatment in trauma and medical patients with potential life-threatening conditions. The goal of primary assessment is to identify and address life-threatening situations immediately. For nurses, the primary survey represents the initial stage of patient assessment and functions not merely as a data collection exercise but as a critical process for the early recognition of clinical deterioration [A15].

(2) Situation awareness and intuition

Situational awareness refers to the ability to rapidly detect changes in a patient’s condition, interpret these changes, and prepare an appropriate clinical response [

18]. This constitutes the first step in decision-making and enables nurses to anticipate future clinical developments [

19]. Previous clinical care experience is a major contributor to a nurse’s ability to detect patient changes at an early stage [A13].

The importance of intuition within nurses’ competencies for assessing deteriorating patients is increasingly recognized, emphasizing that detection of deterioration extends beyond monitoring physiological changes or vital signs alone [A22]. The Dutch Early Nurse Worry Indicator Score (DENWIS) includes indicators such as changes in respiration, circulation, temperature, mental status, anxiety, pain, unexpected symptoms, a general feeling of unwellness reported by the patient, subjective nurse observations, and intuition without objective evidence [

20]. A distinguishing feature of this tool is its inclusion of subjective indicators, such as anxiety, pain, and patient-expressed concerns, beyond vital signs. Intuitive insights allow nurses to identify high-risk patients earlier, even when vital signs have not reached abnormal thresholds, underscoring the role of “worry” as a precursor to clinical deterioration [

20,A15].

(3) Decision-making ability

Decision-making ability refers to the nurse’s capacity to promptly select and implement the most appropriate interventions in situations of clinical deterioration [A5]. Nurses must assess the degree of patient deterioration and determine whether escalation of treatment is warranted. Even when familiar with RRS activation criteria, nurses may rely more heavily on their clinical judgment and personal experience than on strictly following protocols or predetermined rules [A5,A11]. Nurses are expected to choose the most effective course of action in a given situation, directly affecting patient safety.

In clinical decision-making, nurses assess not only physiological variables, but also factors such as potential instability, illness severity, nursing records, and patient baseline information. EWS serve as valuable tools to support decision-making in these situations [A22]. Continuous patient surveillance is essential to collect the data necessary for informed decisions [A15]. Accurate assessment enables nurses to recognize subtle changes in clinical status, facilitating timely and appropriate responses.

(4) Communication and teamwork for escalation

To ensure timely and effective escalation of care, nurses must be able to communicate clearly and collaborate efficiently with multidisciplinary teams. This includes overcoming hierarchical barriers that may exist between physicians, nurses, and other healthcare professionals [A5]. Communication is pivotal in the escalation process; delays are often attributed to negative attitudes toward seeking assistance [A26]. Nurses frequently report anxiety and uncertainty about when and how to activate escalation protocols, even when deterioration is recognized.

A Korean study examining communication during clinical deterioration events found that “timeliness” scored highly, whereas “openness” scored lowest, highlighting persistent issues related to hierarchical culture within hospital settings [A23].

5) Consequences

Consequences refer to the outcomes or effects that occur when the concept is enacted [

16]. This study explored the question: “What are the expected outcomes of nursing competency in coping with clinical deterioration?” The anticipated outcomes are as follows:

(1) Improvement in patient safety

Early recognition of clinical deterioration significantly improves patient outcomes and safety [A11]. Timely and appropriate responses can prevent progression of deterioration and facilitate rapid stabilization of the patient’s condition. Delayed responses to deterioration are associated with lower survival rates and poorer clinical outcomes [

4]. All nurses must provide high-quality, safe care to achieve optimal outcomes. Nurse managers should be aware of the competencies needed to identify and respond to clinical deterioration, as these directly impact patient outcomes [A34]. Additionally, a positive nursing practice environment is associated with reduced patient mortality, indicating that improvements in work environments contribute to safer patient care [A8].

(2) Enhanced confidence of nurses

Confidence refers to a nurse’s belief in their ability to successfully perform a given task [A22]. Repeated experience in managing clinical deterioration enhances confidence and strengthens a nurse’s capacity to respond effectively in similar situations. Negative emotions such as stress and anxiety in response to clinical deterioration can be mitigated through increased confidence and self-efficacy [A22]. Conversely, a lack of confidence may hinder a nurse’s ability to manage clinical deterioration effectively [A5]. Confidence is critical in various clinical processes, including nursing performance, vital sign assessment, patient monitoring, clinical decision-making, communication with physicians, RRT activation, and treatment escalation [A15,A34]. Furthermore, hospital organizational culture should shift from blaming individual nurses for inexperience or system failures to promoting mutual support and collaboration [A16].

DISCUSSION

Although the importance of coping with clinical deterioration has been widely recognized through practical experience in various countries and healthcare institutions, the concept of clinical status deterioration itself remains poorly defined. This lack of clear and systematic understanding has made it difficult to elucidate the development of core nursing competencies, integrate these competencies into nursing curricula, and establish relevant policy frameworks.

This study applied Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis method to clarify the concept of nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration, focusing on its development across temporal and cultural contexts. The analysis confirmed that this concept has evolved dynamically over the past two decades, closely mirroring advancements in patient safety systems, technology adoption, and the professionalization of nursing roles—particularly in countries such as Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, where RRSs were introduced and standardized earlier [

8-

10].

The clarified concept of nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration refers to a multifaceted capacity encompassing nurses’ abilities to assess patient circumstances, monitor vital signs, apply clinical intuition, and engage in effective communication and teamwork with colleagues and RRTs. This integrative view reflects the increasingly complex role of nurses in ensuring early recognition and appropriate escalation in deteriorating patient situations.

First, this study explored the temporal and contextual evolution of the concept. The review of 35 international studies over a 25-year period highlighted how nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration has transitioned from a focus on technical, task-based competencies to a holistic, leadership-oriented model. During the initial phase (2000–2010), nursing roles in patient deterioration management were largely concentrated on physiological assessment, vital signs monitoring, and primary survey (ABCD) [A5,A12,A13]. Nurses primarily acted as data collectors and reporters, with limited involvement in decision-making or escalation. Between 2011 and 2020, with the global spread of EWS and RRS systems, the focus expanded to include situational awareness, interdisciplinary communication, and structured escalation protocols [A3,A8,A22]. Nurses increasingly became recognized as active participants in patient safety teams, requiring competencies in recognizing deterioration, collaborating across disciplines, and initiating escalation [A15,A20,A26].

From 2021 onward, the concept has further evolved toward proactive nursing leadership, clinical advocacy, and advanced decision-making in the early stages of deterioration [A19,A24,A25,A34]. Nurses are now expected to initiate interventions, lead team communication, and advocate for improvements in patient safety culture at the organizational level, often supported by advanced technologies such as AI-assisted monitoring [

21-

23].

These changes reflect global healthcare trends, including an aging population, the rise in chronic diseases, and increased emphasis on safety culture and interdisciplinary teamwork [

2,

4,

8]. Notably, heightened patient acuity and complexity have raised expectations for nurses' leadership in escalation processes and critical care management [

12].

Second, this study examined cultural and contextual reflections using the case of Korea. The Korean healthcare system is at an earlier stage of this evolution; the Korean RRS was only institutionalized in 2019 [

11], and nursing roles in clinical deterioration remain limited within a hierarchical, physician-centered model. This constrains nurses' autonomy and decision-making authority. Korean nurses continue to encounter barriers such as high patient loads, insufficient staffing, rigid reporting structures, and hierarchical cultural norms, all of which hinder their ability to exercise core competencies such as situational awareness, proactive decision-making, and interdisciplinary collaboration.

While the international literature consistently emphasizes the necessity of leadership empowerment, communication skill development, and simulation-based training [

19,

20,

22], these elements remain underdeveloped in the Korean nursing context, highlighting the need for deliberate adaptation of globally derived concepts to address local sociocultural and organizational constraints.

Third, the findings of this concept analysis have significant implications for Korean nursing practice and policy development. Based on the clarified concept and its evolutionary trajectory, several strategic implications are proposed for Korean nursing practice and policy. First, educational reforms are urgently needed to move beyond the traditional focus on technical skills. Incorporating scenario-based simulations, reflective learning from adverse events, and critical thinking workshops are essential strategies to foster competencies aligned with the proactive and integrative roles required for managing clinical deterioration [

23,

24].

Additionally, policy reforms should consider enabling nurses to activate the RRS independently, without prior physician approval, as successfully implemented in countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia [

9-

12]. From an organizational perspective, workforce management strategies must prioritize maintaining safe patient-to-nurse ratios, especially during night shifts, to establish an environment where clinical decision-making and escalation processes can be executed promptly and effectively [

11,

12].

Furthermore, there is a critical need to implement culturally sensitive communication training programs—such as SBAR frameworks adapted to the specific dynamics of Korean clinical settings—to address nurses’ hesitation and uncertainty regarding communication and escalation. These strategic directions align with global recommendations emphasizing interdisciplinary collaboration, nurse empowerment within patient safety systems, and the promotion of proactive behaviors for timely escalation in deteriorating patient situations [

1,

4,

8,

11].

This study is the first to systematically clarify the concept of nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration using Rodgers’ evolutionary method, incorporating both historical and cultural perspectives. Unlike previous domestic studies that focused on isolated skills, this research presents a comprehensive, leadership-oriented conceptual model that aligns with international standards while also addressing Korea’s unique healthcare context.

By broadening the scope of nursing competence beyond traditional emergency care, the clarified concept integrates key attributes such as patient assessment, vital signs monitoring, situational awareness, intuition, clinical decision-making, and team communication. These competencies directly contribute to improved patient safety, enhanced nurse confidence, and strengthened professional autonomy.

Furthermore, this study provides a theoretical foundation for the development of nurse-led escalation systems, informs policy reforms, and guides the redesign of nursing education in Korea. Effective management of clinical deterioration not only improves patient outcomes but also promotes a culture of collaboration and mutual support within healthcare organizations [A35].

A notable limitation of this study is the lack of domestic literature, necessitating reliance on international sources for concept clarification. Given the increasing patient acuity associated with an aging population, chronic diseases, and emerging infectious diseases such as coronavirus disease 2019, further research is required to refine and contextualize this concept within Korean clinical settings. Future studies should focus on developing reliable assessment tools for evaluating nurses’ response competencies to deterioration, and on designing simulation-based education programs to enhance these capabilities. Additionally, research should examine barriers to recognition and escalation, and propose strategies to overcome them, with an emphasis on fostering effective communication and teamwork among nurses, physicians, and RRS teams.

CONCLUSION

This study clarified the concept of nursing competence in coping with clinical deterioration using Rodgers’ evolutionary concept analysis method, based on a review of 35 international studies from 2000 to 2025. The analysis demonstrated that nursing competence has evolved from a task-oriented focus to an integrated model emphasizing early recognition, clinical judgment, decision-making, communication, and leadership.

Key conceptual attributes were identified, including technical skills, situational awareness, critical thinking, and interprofessional collaboration. Antecedents such as clinical experience, structured education, and simulation-based training were shown to be essential for developing competence, while influencing factors included organizational culture, staffing levels, and system support (e.g., EWS, RRS). Competent nursing responses were consistently linked to improved patient safety, timely escalation, and increased nurse confidence.

Cross-national comparisons revealed that Western countries have adopted proactive, nurse-led escalation systems more fully than countries still in earlier stages of implementation, such as Korea. These findings suggest the need for contextual adaptation, especially in settings with hierarchical clinical structures and limited nurse autonomy.

The clarified concept provides a foundational framework for developing educational curricula, institutional policies, and competency assessment tools aimed at enhancing nurses’ ability to respond effectively to clinical deterioration. Future efforts should prioritize empowerment, simulation-based training, and system-level support to strengthen nursing leadership in acute care settings and promote patient safety outcomes.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author declared no conflict of interest.

-

FUNDING

None.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Park Soo-hyung, Senior Clinical Research Associate at Premier Research, for dedicated assistance with data collection and coordination throughout the study.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data can be obtained from the corresponding authors.

Figure 1.Flow of study analysis through the different phases of the literature review.

Figure 2.Antecedents, attributes, and consequences of competency to cope with clinical deterioration.

Table 1.Concept Analysis of the Research Papers Included in the Review (N=35)

|

Authors (year) |

Nation |

Purpose/focus |

Design |

Concept definition |

|

A1 |

Azimirad et al. (2022) |

Finland |

Explore nurse assessments of deteriorating patients |

Qualitative |

Clinical competence |

|

A2 |

Bacon (2017) |

USA |

Lived experiences of nurses with patients who die due to failure to rescue |

Qualitative |

Nurses’ role |

|

A3 |

Burke and Conway (2023) |

Ireland |

Factors influencing nurses' escalation of care |

Qualitative |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A4 |

Butler (2018) |

UK |

Nurses' experiences post-education on managing deterioration |

Qualitative |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A5 |

Chua et al. (2020) |

Singapore |

Enhance doctor-nurse collaboration in escalations |

Qualitative |

Nurses’ role |

|

A6 |

Chua et al. (2013) |

Singapore |

Experience of frontline nurses with deteriorating patients |

Qualitative |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A7 |

Chua et al. (2023) |

Singapore |

Impact of automated rapid response systems |

Mixed methods |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A8 |

Al-Ghraiybah et al. (2024) |

Australia |

Effect of nursing environment, staffing, and surveillance on patient mortality |

Descriptive |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A9 |

Al-Moteri et al. (2020) |

Australia, Saudi Arabia |

Examine cognitive biases in recognizing deterioration cues |

Experimental |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A10 |

Allen (2020) |

USA |

Identify barriers for non-critical care nurses in recognizing and responding to early signs of clinical deterioration |

Literature review |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A11 |

Foley and Dowling (2019) |

UK |

Investigate how nurses use early warning scores in acute settings |

Case study |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A12 |

Wood et al. (2019) |

Australia |

Explore early warning score use for detecting patient deterioration |

Literature review |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A13 |

Dalton et al. (2018) |

UK |

Identify factors influencing nurses' assessment of patient acuity |

Qualitative study |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A14 |

Douglas et al. (2014) |

Australia |

Develop and test a scale for barriers to nurses' physical assessment |

Instrument development study |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A15 |

Dalton (2022) |

UK |

Understand nurses' recognition and response to patient deterioration |

Mixed methods |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A16 |

Dresser et al. (2023) |

USA |

Examine factors influencing nurses' clinical judgment in identifying and responding to deterioration |

Qualitative |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A17 |

Fontenot et al. (2022) |

USA |

Assess impact of standardized physical assessment program on early recognition of deterioration |

Quasi-experimental |

Clinical competence |

|

A18 |

Gazarian et al. (2010) |

USA |

Explore decision-making cues used by nurses in pre-arrest situations |

Qualitative |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A19 |

Douw et al. (2016) |

Netherlands |

Evaluate Dutch Early Nurse Worry Indicator Score (DENWIS) for early detection of deterioration |

Observational |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A20 |

Duff et al. (2018) |

Australia |

Evaluate the impact of the DeTER program on skills in recognizing and responding to deterioration |

Quasi-experimental |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A21 |

Haegdorens et al. (2023) |

Belgium |

Assess the predictive value of combining the Nurse Intuition Patient Deterioration Scale (NIPDS) with the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) for predicting serious adverse events |

Prospective cohort study |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A22 |

Jensen et al. (2018) |

Norway |

Describe and synthesize the impact of early warning scores and rapid response systems on nurses’ competence |

Literature review |

Nurses’ competence |

|

A23 |

Jin et al. (2022) |

Korea |

Examine nurses' perception and performance in communication during clinical deterioration |

Descriptive |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A24 |

Lavoie et al. (2020) |

Canada |

Investigate agreement between nurse judgments at handoffs and early warning scores |

Observational |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A25 |

Liu et al. (2024) |

China |

Evaluate the effectiveness of educational strategies for recognizing deterioration |

Literature review |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A26 |

Massey et al. (2017) |

Australia |

Identify factors influencing ward nurses’ recognition and response to deterioration |

Literature review |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A27 |

Mbuthia et al. (2024) |

Kenya |

Explore detection and response to clinical deterioration by general ward nurses |

Mixed-methods |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A28 |

Odell et al. (2009) |

UK |

Examine the role of nurses in detecting deterioration in ward patients |

Literature review |

Nurses’ role |

|

A29 |

Orique et al. (2019) |

USA |

Examine capacity and tendency of nurses to perceive deterioration cues |

Descriptive |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A30 |

Hart et al. (2014) |

USA |

Explore perceived self-confidence and leadership abilities in deterioration events |

Descriptive |

Nurses’ role |

|

A31 |

Peebles et al. (2020) |

Australia |

Evaluate a just-in-time training program to improve response to deterioration |

Quasi-experimental |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A32 |

Rosli et al. (2023) |

Malaysia |

Determine critical care nurses' physical assessment skills usage |

Descriptive |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A33 |

Warren et al. (2021) |

USA |

Evaluate impact of Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) on knowledge and response to deterioration |

Quasi-experimental |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A34 |

Xu et al. (2023) |

China |

Develop and validate tool to measure junior nurses’ response abilities |

Mixed-methods |

Nurses’ ability |

|

A35 |

Donnelly et al. (2024) |

UK |

Explore, map and synthesize existing research related to the ward nurses’ role in recognizing and responding to clinical deterioration |

Literature review |

Nurses’ role |

Table 2.Derivation of Components on Nursing Competency to Cope with Clinical Deterioration

|

Component |

Derived elements |

Summary of derivation process |

Representative references |

|

Antecedents |

Education and training: |

Identified as essential preparatory factors to develop necessary competencies. Many studies emphasized the critical role of structured training, simulation, and system familiarity in improving nurses' readiness for clinical deterioration situations. |

[A15,A22,A25,A31] |

|

Comprehensive education, simulation-based training, and updated knowledge on EWS and RRS systems |

|

Clinical experience: |

Derived from descriptions of experiential learning improving situational awareness and decision-making. Studies consistently reported that repeated exposure to clinical deterioration cases strengthens nurses’ intuitive and judgmental skills. |

[A15,A25] |

|

Accumulation of bedside experience in recognizing and managing clinical deterioration |

|

Resources and system support: |

Synthesized from studies highlighting the necessity of accessible tools and system infrastructure to support timely recognition, decision-making, and care escalation. |

[A3,A22] |

|

Availability and accessibility of systems such as EWS, RRS, supportive policies, and resource adequacy |

|

Attributes |

Technical skills: |

Consolidated from studies reporting the need for nurses’ technical proficiency in assessments and interventions as fundamental attributes in deterioration response. |

[A15,A29,A34,A35] |

|

Vital signs monitoring, physical assessment, ABCD assessment, and timely intervention skills |

|

Situational awareness and intuition: |

Frequently noted in studies describing the importance of situational awareness and intuitive reasoning, especially when vital signs alone do not capture the full clinical picture. |

[A13,A15,A22,A29] |

|

Ability to detect subtle changes, interpret early deterioration cues, and apply clinical intuition |

|

Decision-making skills: |

Extracted from studies detailing the nurse’s role in critical judgment and escalation decision-making during patient deterioration events. |

[A5,A11,A15,A22] |

|

Clinical reasoning, independent judgment, and decision-making in escalation scenarios |

|

Communication and teamwork for escalation: |

Repeatedly emphasized in the literature as key components enabling timely escalation and collaborative interventions during emergencies. |

[A5,A23,A26] |

|

Clear communication, interdisciplinary teamwork, and leadership in escalation |

|

Consequences |

Improvement in patient safety: |

Reported as primary outcomes from effective recognition and response to deterioration, leading to better clinical outcomes and reduced patient harm. |

[A4,A5,A11,A15,A22] |

|

Prevention of deterioration events, reduction of mortality and adverse outcomes |

|

Enhanced confidence of nurses: |

Derived from studies demonstrating improved nurse confidence and leadership capabilities after gaining experience and success in managing clinical deterioration events. |

[A5,A15,A22,A34] |

|

Increased self-efficacy, professional autonomy, and leadership capabilities in managing clinical deterioration |

|

Affecting factors |

Individual factors: |

Synthesized from descriptions across studies where personal, organizational, and environmental contexts influenced the development and application of nurses' competencies. Especially noted were the impact of workload, team dynamics, system availability, and institutional support on nurses' timely and safe response to deterioration. |

[A3,A5,A8,A16,A21,A23,A28,A30,A33,A34,A35] |

|

Clinical knowledge, skills, experience, self-confidence |

|

Task factors: |

|

Complexity of clinical judgment, workload in deterioration scenarios |

|

Organizational factors: |

|

Hierarchical culture, leadership support, teamwork environment |

|

Environmental factors: |

|

Availability of monitoring tools, staffing, access to RRS, EWS |

REFERENCES

- 1. Andersen LW, Holmberg MJ, Berg KM, Donnino MW, Granfeldt A. In-hospital cardiac arrest: a review. JAMA. 2019;321(12):1200-10. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.1696

- 2. Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146-603. https://doi.org/10.1161/cir.0000000000000485

- 3. Andersen LW, Kim WY, Chase M, Berg KM, Mortensen SJ, Moskowitz A, et al. The prevalence and significance of abnormal vital signs prior to in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016;98:112-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.08.016

- 4. Gaughan MR, Jungquist CR. Patient deterioration on general care units: a concept analysis. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2022;45(2):E56-68. https://doi.org/10.1097/ans.0000000000000396

- 5. Jones D, Mitchell I, Hillman K, Story D. Defining clinical deterioration. Resuscitation. 2013;84(8):1029-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.013

- 6. Padilla RM, Mayo AM. Clinical deterioration: a concept analysis. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(7-8):1360-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14238

- 7. Campbell B, Mackay G. Continuing competence: an Ontario nursing regulatory program that supports nurses and employers. Nurs Adm Q. 2001;25(2):22-30. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006216-200101000-00006

- 8. Baehrend J. 100,000 lives campaign: ten years later [Internet]. Boston, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2016 [cited 2025 March 17]. Available from: https://www.ihi.org/library/blog/100000-lives-campaign-ten-years-later

- 9. Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. National safety and quality primary and community healthcare standards [Internet]. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2017 [cited 2025 March 17]. Available from: https://www.practiceassist.com.au/PracticeAssist/media/Practice-Connect/National-Safety-and-Quality-Primary-and-Community-Healthcare-Standards-October-2021.pdf

- 10. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Acutely ill adults in hospital: recognising and responding to deterioration [Internet]. London: NICE; 2007 [cited 2007 February 10]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg50

- 11. Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Ministry of Health and Welfare announcement no. 2019-223: call for pilot institutions for the rapid response system [Internet]. Cheongju: KDCA; 2022 [cited 2025 March 17]. Available from: https://www.mohw.go.kr/board.es?mid=a10501010200&bid=0003&act=view&list_no=348050

- 12. Sessim-Filho J, Azevedo RP, Assuncao-Jr AN, Morgado M, Silva FD, Pastore LJ, et al. Dedicated rapid response team implementation associated with reductions in hospital mortality and hospital expenses: a retrospective cohort analysis. Int J Qual Health Care. 2025;37(2):mzaf030. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzaf030

- 13. Tirkkonen J, Skrifvars MB, Tamminen T, Parr MJ, Hillman K, Efendijev I, et al. Afferent limb failure revisited: a retrospective, international, multicentre, cohort study of delayed rapid response team calls. Resuscitation. 2020;156:6-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.08.117

- 14. Park H, Kim Y, Chu SH. Importance-performance analysis (IPA) to improve emergency care for novice nurses. J Korean Acad Fundam Nurs. 2019;26(3):155-65. https://doi.org/10.7739/jkafn.2019.26.3.155

- 15. Kim HY. Analysis of emergency nursing competency, facilitating and inhibiting factors for the activation of rapid response teams among nurses [master’s thesis]. Seoul: The Catholic University of Korea; 2023.

- 16. Rodgers BL, Knafl KA. Concept development in nursing: foundations, techniques, and applications. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2000.

- 17. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- 18. Endsley MR. Situation awareness misconceptions and misunderstandings. J Cogn Eng Decis Mak. 2015;9(1):4-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555343415572631

- 19. Chua WL, Legido-Quigley H, Ng PY, McKenna L, Hassan NB, Liaw SY. Seeing the whole picture in enrolled and registered nurses' experiences in recognizing clinical deterioration in general ward patients: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;95:56-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.04.012

- 20. Douw G, Huisman-de Waal G, van Zanten AR, van der Hoeven JG, Schoonhoven L. Surgical ward nurses' responses to worry: an observational descriptive study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;85:90-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.05.009

- 21. Mok WQ, Wang W, Liaw SY. Vital signs monitoring to detect patient deterioration: an integrative literature review. Int J Nurs Pract. 2015;21 Suppl 2:91-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12329

- 22. Della Ratta C. The art of balance: preceptors' experiences of caring for deteriorating patients. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(19-20):3497-509. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14579

- 23. Tutticci N, Johnston S, Gillan P, McEnroe G, Lesse R, Currie J, et al. Simulation strategies to develop undergraduate nurses' skills to identify patient deterioration: a quasi-experimental study. Clin Simul Nurs. 2024;91:101534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2024.101534

- 24. Smith D, Cartwright M, Dyson J, Hartin J, Aitken LM. Barriers and enablers of recognition and response to deteriorating patients in the acute hospital setting: a theory-driven interview study using the Theoretical Domains Framework. J Adv Nurs. 2021;77(6):2831-44. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14830

Appendices

Appendix 1.

- List of Studies Included in Concept Analysis

A1 Azimirad M, Magnusson C, Wiseman A, Selander T, Parviainen I, Turunen H. Identifying teamwork-related needs of the medical emergency team: nurses' perspectives. Nurs Crit Care. 2022;27(6):804-14.

https://doi.org/10.1111/nicc.12676

A3 Burke C, Conway Y. Factors that influence hospital nurses' escalation of patient care in response to their early warning score: a qualitative evidence synthesis. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(9-10):1885-934.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16233

A4 Butler C. Nurses’ experiences of managing patient deterioration following a post-registration education programme: a critical incident analysis study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2018;28:96-102.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2017.10.014

A5 Chua WL, Legido-Quigley H, Jones D, Hassan NB, Tee A, Liaw SY. A call for better doctor-nurse collaboration: a qualitative study of the experiences of junior doctors and nurses in escalating care for deteriorating ward patients. Aust Crit Care. 2020;33(1):54-61.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2019.01.006

A6 Chua WL, Mackey S, Ng EK, Liaw SY. Front line nurses’ experiences with deteriorating ward patients: a qualitative study. Int Nurs Rev. 2013;60(4):501-9.

https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12061

A7 Chua WL, Wee LC, Lim JY, Yeo ML, Jones D, Tan CK, et al. Automated rapid response system activation: impact on nurses' attitudes and perceptions towards recognising and responding to clinical deterioration: mixed-methods study. J Clin Nurs. 2023;32(17-18):6322-38.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.16734

A8 Al-Ghraiybah T, Lago L, Fernandez R, Sim J. Effects of the nursing practice environment, nurse staffing, patient surveillance and escalation of care on patient mortality: a multi-source quantitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2024;156:104777.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2024.104777

A9 Al-Moteri M, Cooper S, Symmons M, Plummer V. Nurses' cognitive and perceptual bias in the identification of clinical deterioration cues. Aust Crit Care. 2020;33(4):333-42.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2019.08.006

A10 Allen G. Barriers to non-critical care nurses identifying and responding to early signs of clinical deterioration in acute care facilities. Medsurg Nurs. 2020;29(1):43-52.

A11 Foley C, Dowling M. How do nurses use the early warning score in their practice? A case study from an acute medical unit. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(7-8):1183-92.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14713

A12 Wood C, Chaboyer W, Carr P. How do nurses use early warning scoring systems to detect and act on patient deterioration to ensure patient safety? A scoping review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;94:166-78.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.03.012

A14 Douglas C, Osborne S, Reid C, Batch M, Hollingdrake O, Gardner G, et al. What factors influence nurses' assessment practices? Development of the Barriers to Nurses' use of Physical Assessment Scale. J Adv Nurs. 2014;70(11):2683-94.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12408

A15 Dalton MA. Understanding the process of nurses’ recognition and response to patient deterioration [dissertation]. Liverpool: Liverpool John Moores University; 2022.

A16 Dresser S, Teel C, Peltzer J. Frontline nurses’ clinical judgment in recognizing, understanding, and responding to patient deterioration: a qualitative study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2023;139:104436.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2023.104436

A17 Fontenot NM, Hamlin SK, Hooker SJ, Vazquez T, Chen HM. Physical assessment competencies for nurses: a quality improvement initiative. Nurs Forum. 2022;57(4):710-6.

https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12725

A19 Douw G, Huisman-de Waal G, van Zanten AR, van der Hoeven JG, Schoonhoven L. Nurses' 'worry' as predictor of deteriorating surgical ward patients: a prospective cohort study of the Dutch-Early-Nurse-Worry-Indicator-Score. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;59:134-40.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.04.006

A20 Duff B, Massey D, Gooch R, Wallis M. The impact of a multimodal education strategy (the DeTER program) on nurses' recognition and response to deteriorating patients. Nurse Educ Pract. 2018;31:130-5.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2018.05.011

A21 Haegdorens F, Wils C, Franck E. Predicting patient deterioration by nurse intuition: The development and validation of the nurse intuition patient deterioration scale. Int J Nurs Stud. 2023;142:104467.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2023.104467

A22 Jensen JK, Skar R, Tveit B. The impact of Early Warning Score and Rapid Response Systems on nurses' competence: an integrative literature review and synthesis. J Clin Nurs. 2018;27(7-8):e1256-74.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14239

A23 Jin BG, Kang K, Cho HJ. Korean nurses' perception and performance on communication with physicians in clinical deterioration. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(38):e30570.

https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000030570

A24 Lavoie P, Clarke SP, Clausen C, Purden M, Emed J, Mailhot T, et al. Nurses' judgments of patient risk of deterioration at change-of-shift handoff: Agreement between nurses and comparison with early warning scores. Heart Lung. 2020;49(4):420-5.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2020.02.037

A25 Liu Q, Xie C, Tan J, Xu L, Zhou F, Peng L. Exploring the nurses' experiences in recognising and managing clinical deterioration in emergency patients: a qualitative study. Aust Crit Care. 2024;37(2):309-17.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2023.06.004

A26 Massey D, Chaboyer W, Anderson V. What factors influence ward nurses' recognition of and response to patient deterioration? An integrative review of the literature. Nurs Open. 2017;4(1):6-23.

https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.53

A27 Mbuthia N, Kagwanja N, Ngari M, Boga M. General ward nurses detection and response to clinical deterioration in three hospitals at the Kenyan coast: a convergent parallel mixed methods study. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):143.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-01822-2

A29 Orique SB, Despins L, Wakefield BJ, Erdelez S, Vogelsmeier A. Perception of clinical deterioration cues among medical-surgical nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(11):2627-37.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14038

A30 Hart PL, Spiva L, Baio P, Huff B, Whitfield D, Law T, et al. Medical-surgical nurses' perceived self-confidence and leadership abilities as first responders in acute patient deterioration events. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(19-20):2769-78.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12523

A31 Peebles RC, Nicholson IK, Schlieff J, Peat A, Brewster DJ. Nurses' just-in-time training for clinical deterioration: development, implementation and evaluation. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;84:104265.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104265

A32 Rosli SN, Soh KL, Ong SL, Halain AA, Abdul Raman R, Soh KG. Physical assessment skills practised by critical care nurses: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Crit Care. 2023;28(1):109-19.

https://doi.org/10.1111/nicc.12748

A33 Warren T, Moore LC, Roberts S, Darby L. Impact of a modified early warning score on nurses' recognition and response to clinical deterioration. J Nurs Manag. 2021;29(5):1141-8.

https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13252

A34 Xu L, Tan J, Chen Q, Luo Z, Song L, Liu Q, et al. Development and validation of an instrument for measuring junior nurses' recognition and response abilities to clinical deterioration (RRCD). Aust Crit Care. 2023;36(5):754-61.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aucc.2022.09.010

A35 Donnelly N, Fry M, Elliott R, Merrick E. The role of the ward nurse in recognition and response to clinical deterioration: a scoping review. Contemp Nurse. 2024;60(6):584-613.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2024.2413125