Abstract

-

Purpose

Falls and medication errors are the most common patient safety incidents globally. Kolb’s experiential learning theory supports the application of cognitive learning in clinical settings. This study examined the effectiveness of Experiential Learning–Based Fall and Medication Error Prevention Education (EFMPE), utilizing virtual reality and room of errors.

-

Methods

A randomized controlled trial was conducted with 28 fourth-year nursing students (15 experimental, 13 control). The experimental group participated in EFMPE from February 1 to 6, 2024, comprising six sessions of 2 hours each. The control group received traditional lectures. Safety control confidence and course interest were measured before and immediately after the intervention; safety control confidence was reassessed 6 weeks later.

-

Results

Both groups showed immediate improvement; however, only the experimental group sustained increased safety control confidence after 6 weeks (Wald χ2=13.21, p<.001). Course interest was significantly higher in the experimental group post-intervention (Wald χ2=10.64, p=.001).

-

Conclusion

These preliminary findings suggest that EFMPE potentially supports the prevention of falls and medication errors in clinical practice.

-

Key Words: Education, nursing; Medical errors; Students, nursing; Virtual reality

INTRODUCTION

Medical error refers to the failure to perform intended healthcare activities or inadequate planning of these activities, leading to patient safety incidents. Since the initiation of the Korean Patient Safety Incident Reporting & Learning System in 2016, falls and medication errors have consistently been reported as the most frequent patient safety incidents, as documented in the latest 2023 Patient Safety Statistics Annual Report [

1]. Falls represent a significant global clinical challenge, frequently causing severe consequences such as hip fractures, intracranial hemorrhages, and fatalities [

1,

2].

Medication errors significantly contribute to preventable harm within healthcare settings, resulting in adverse drug reactions, prolonged hospitalizations, and elevated medical costs worldwide [

1,

3]. The global economic impact of medication errors is substantial, with country-specific examples highlighting their severity. In England’s National Health Service, approximately 237 million medication errors occur annually, incurring an economic burden of about £98,462,582 per year [

3]. Given the substantial clinical and economic impacts, falls and medication errors are critical topics for educators developing medical error prevention programs.

Nursing students, as future healthcare providers, play a crucial role in identifying and preventing medical errors. Students encountering patient safety incidents in clinical settings often experience heightened alertness, stress, and self-doubt regarding their knowledge and skills, potentially leading them to consider discontinuing their studies [

4]. Discrepancies between theoretical knowledge and practical clinical experience, particularly concerning patient safety risks, contribute to feelings of disappointment and frustration [

5]. Thus, education methods that effectively bridge theoretical knowledge and clinical application are essential.

Experiential learning is a valuable approach in clinical education for addressing the gap between theory and practice [

6,

7]. Kolb’s experiential learning theory posits that learning is a cyclical process, where individuals first engage in concrete experiences, then reflect on those experiences, develop abstract concepts based on their reflections, and finally test these concepts through active experimentation (concrete experience [CE]) [

8]. This cycle enhances the internalization of knowledge [

7,

8]. Experiential methods such as simulation and contextual games in nursing education have improved key clinical competencies, including critical thinking and clinical reasoning [

9,

10].

Virtual reality (VR) technology delivers immersive experiences directly to users and has proven effective in various educational settings [

11]. Clinical education on managing medical errors can be challenging due to patient safety and rights concerns. However, VR-based learning safely simulates clinical error scenarios, allowing students to directly manipulate virtual objects [

11,

12]. VR technology thus supports Kolb’s experiential learning stages, notably CE and active experimentation. This study employed VR technology to facilitate firsthand experiences for students.

A “Room of Errors” (ROE) is a simulation method where learners enter a simulated environment to identify potential risks such as falls, medication errors, and patient identification issues [

13,

14]. Numerous studies have used ROE to evaluate learners’ error recognition abilities [

13]. Furthermore, research has demonstrated ROE’s positive effects on learners’ attitudes, self-efficacy, confidence, and skills in error identification and risk management [

13,

14]. Since ROE simulates error scenarios difficult to experience in real clinical environments, it enables students to actively recognize and correct errors. This study uses ROE to support experiential learning effectively.

Previous ROE studies were mainly conducted in simulation labs, where students primarily observed and identified errors [

13,

14]. VR technology, however, allows active interaction and hands-on engagement beyond mere observation [

11]. Integrating VR technology into ROE enhances experiential learning by providing a more immersive, interactive method for students to identify and correct errors.

Safety control confidence refers to an individual's belief in their capability to influence working conditions to prevent hazards [

15], directly affecting their actions and outcomes [

16]. In nursing practice, safety control confidence directly and indirectly impacts nursing performance [

17,

18]. Course interest involves personal curiosity or excitement within educational contexts, driving students’ motivation to engage in learning [

19]. Experiential learning theory suggests that increased course interest fosters greater motivation to learn [

10,

20]. Based on experiential learning theory, safety control confidence and course interest support sustained competency development in preventing falls and medication errors.

This study aimed to develop an Experiential Learning–Based Fall and Medication Error Prevention Education (EFMPE) incorporating a VR-based ROE program and to evaluate its effectiveness by assessing nursing students’ safety control confidence and course interest. The study hypotheses were as follows: Hypothesis 1, The experimental group receiving EFMPE will demonstrate higher safety control confidence than the control group; Hypothesis 2, The experimental group receiving EFMPE will demonstrate higher course interest than the control group.

METHODS

1. Study Design

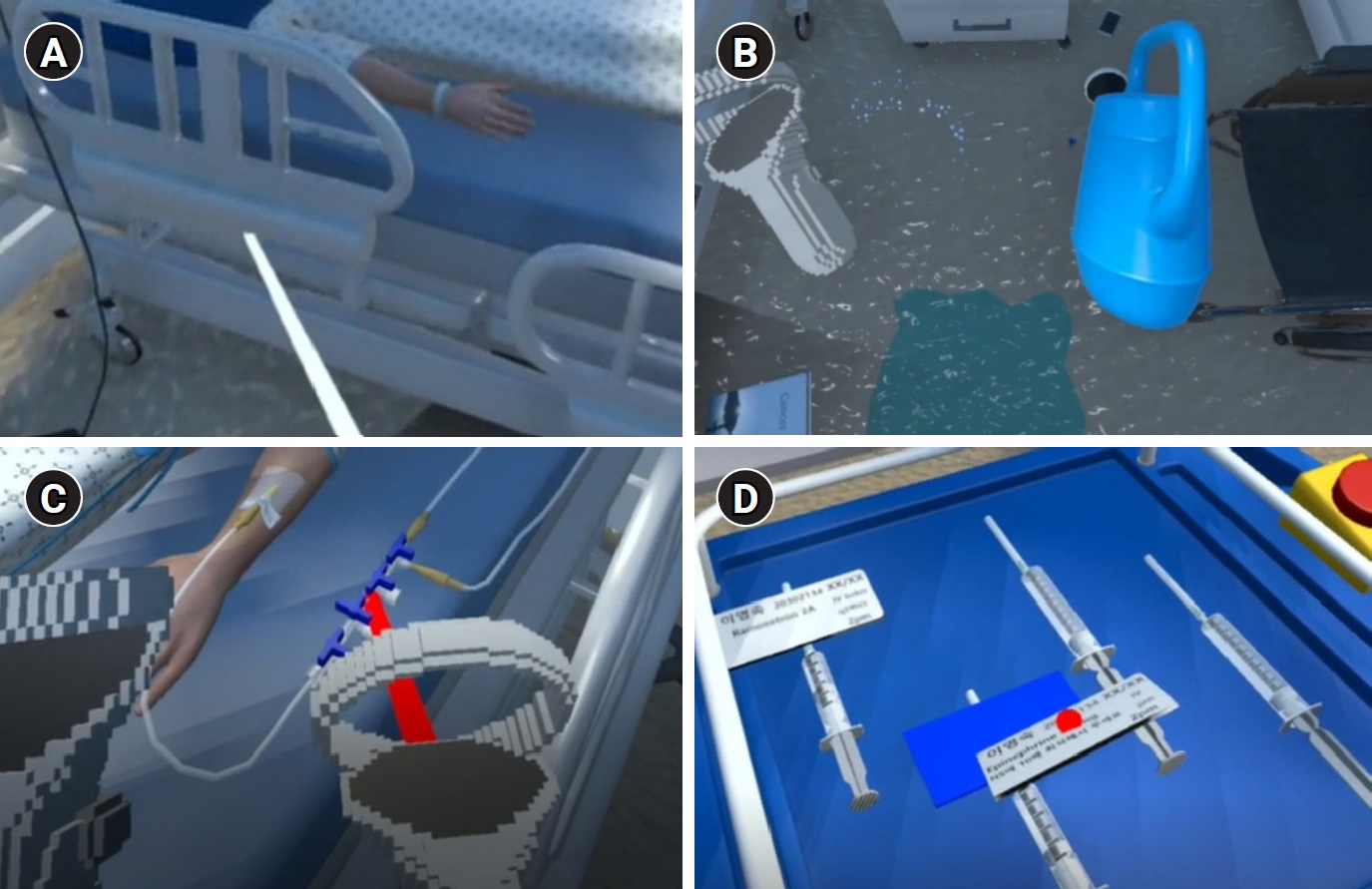

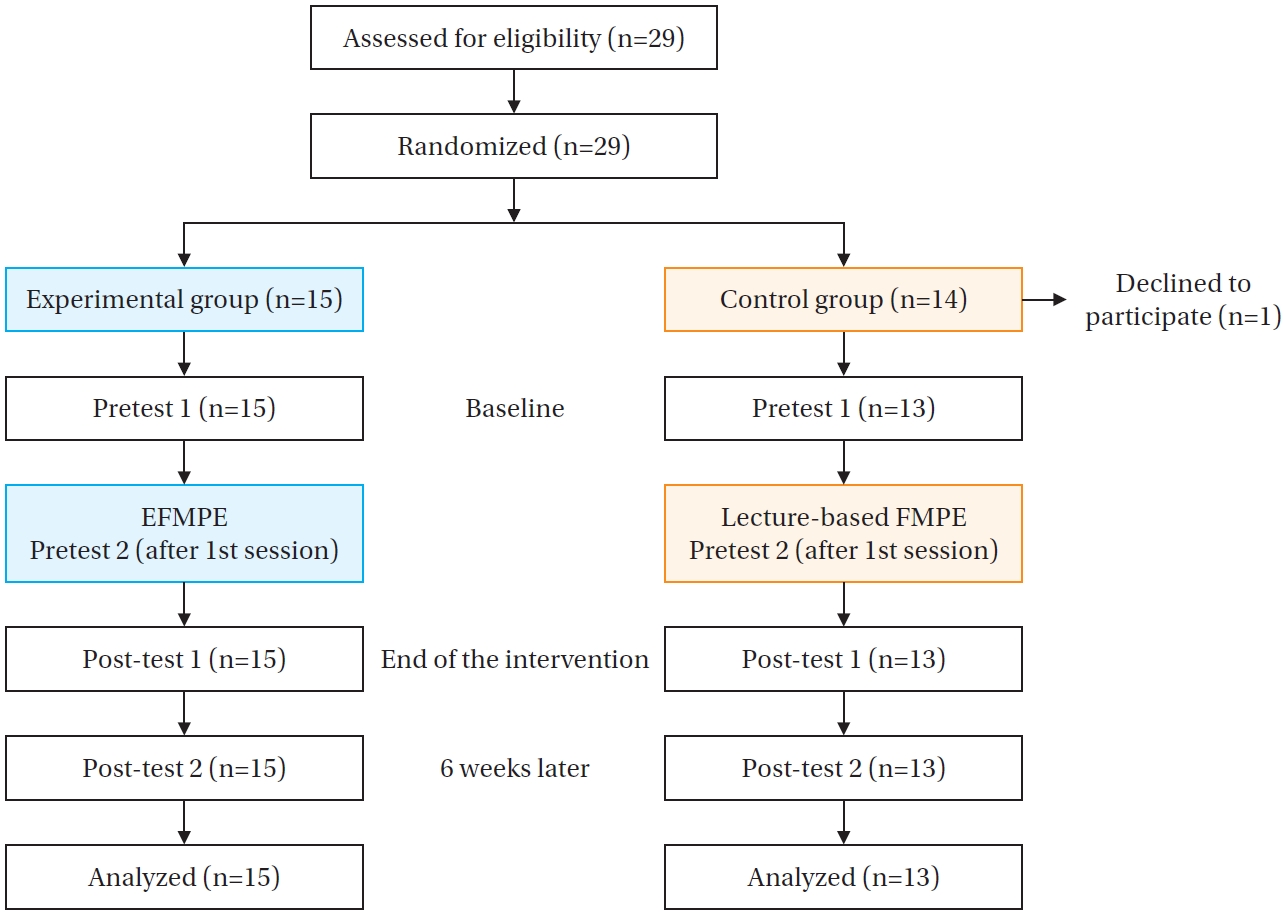

This study utilized a randomized controlled trial to preliminarily evaluate the effectiveness of the EFMPE. The study protocol was not pre-registered in a clinical trial registry since it was designed as a preliminary evaluation. This study was conducted and reported in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guideline.

2. Theoretical Framework

The education was based on Kolb’s experiential learning theory [

8], which promotes the application of learned concepts to clinical practice. Experiential learning is learner-centered and emphasizes real-world experiences to facilitate the understanding of new concepts, enhance problem-solving skills, and enable knowledge application [

7,

21].

Kolb outlined experiential learning as a cycle comprising four stages: CE, reflective observation (RO), abstract conceptualization (AC), and active experimentation (AE) [

8]. The CE stage involves direct engagement with real-world situations in an open, unbiased manner. RO consists of interpreting and reflecting upon learners’ experiences from multiple perspectives, allowing them to consider experiences, interpret their significance, and gain insights. In the AC stage, learners integrate their observations and reflections into new theories or concepts. During this stage, learners synthesize and organize new ideas derived from previous stages into coherent concepts or hypotheses. The AE stage involves applying insights from AC to practical decision-making and problem-solving. This action continues the cyclical learning process by leading back to the CE stage, promoting continuous recognition, reflection, and prevention of falls and medication errors in clinical practice. Thus, structuring EFMPE based on Kolb’s experiential learning cycle supports the expectation of sustained learning outcomes beyond the educational period.

The analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation (ADDIE) model guided the creation and evaluation of the EFMPE [

22]. During the analysis phase, previous studies employing the ROE approach were reviewed to identify risk situations associated with falls or medication errors. A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, EMBASE, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, and RISS using combinations of keywords such as “nursing students,” “nurses,” “Room of Errors,” and “education.” Fall-related errors identified from the literature included situations like “bed rails down” and “spill on the floor,” whereas medication-related errors included “prepared allergic medication for a patient with a known allergy” and “IV fluids not labeled,” among others.

Additionally, six nurses participated in a brainstorming session to share clinical experiences regarding falls and medication errors. The nurses were selected from general wards of a tertiary hospital with over 1,000 beds, each with up to 3 years of clinical experience to capture the perspectives of newer nurses. Participants were asked to describe direct or indirect experiences related to falls and medication errors in the hospital. New fall-related errors such as “caregiver bed with non-locking wheels” and “wearing inappropriate shoes” were identified during this session. For medication errors, participants added “barcode mismatched prescription” and “omissions in verbal prescription orders.”

In the design phase, the EFMPE was structured into six sessions. Session 1 focused on “understanding of medical errors.” Sessions 2 and 3 delivered experiential-based fall prevention education, and sessions 4 and 5 provided experiential-based medication error prevention education, incorporating both theoretical and practical elements. Session 6 addressed “post-patient safety incident management.” Educational content was derived from patient safety literature related to falls and medication errors.

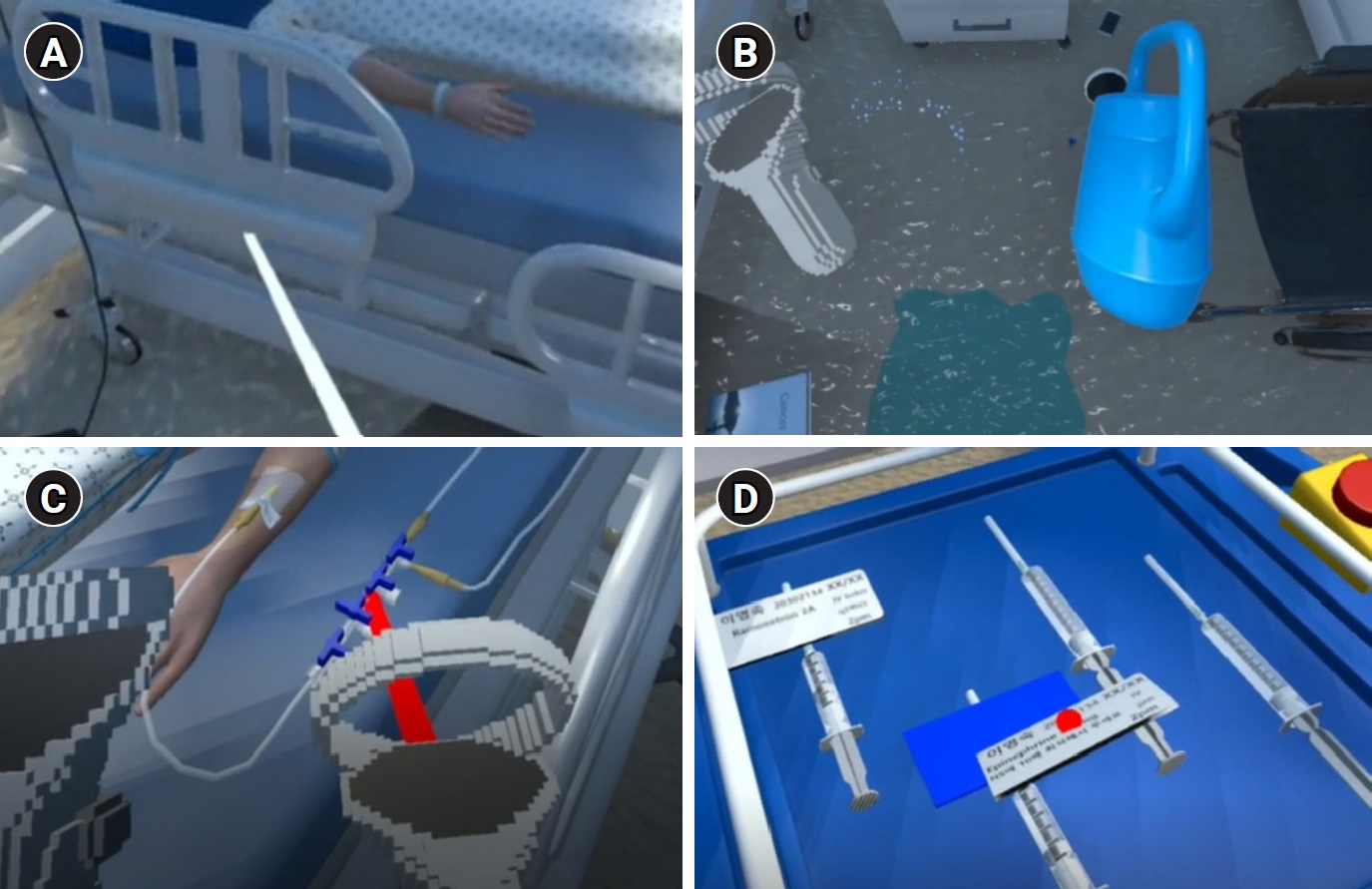

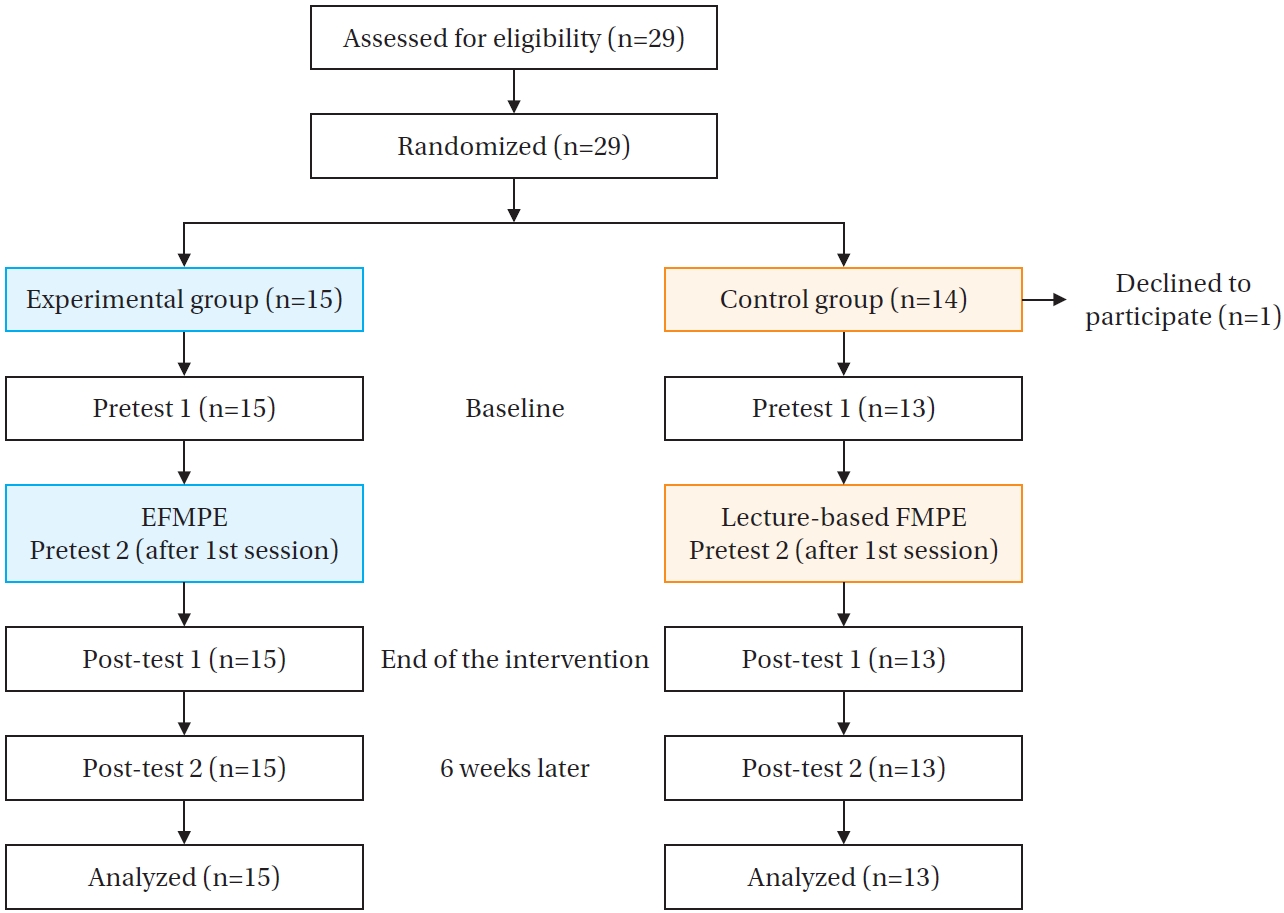

In the development phase, the error situations identified from literature and brainstorming sessions were incorporated. A professional software engineer reviewed the situations for feasibility within a VR setting, using Unity software. The VR ROE was designed with two modules: one for falls and another for medication errors. Both modules were situated in a single-bed room setting. The fall VR ROE module included a storage area containing additional items such as fall caution signs and wall handrails. In the medication VR ROE module, a medication preparation station was positioned adjacent to the bed to minimize user movement. The program operated using Oculus Quest 2, consisting of a head-mounted display and two controllers, allowing learners to set up or correct fall and medication error situations. For example, in the fall VR ROE module, users could increase patient risk by lowering bed rails, dropping items on the floor, or spilling water intentionally. In the medication VR ROE module, medication errors could be induced by misaligning a 3-way valve to obstruct intravenous fluid flow or mislabeling syringes (

Figure 1). The fall VR ROE module included 15 interactive virtual objects or conditions, while the medication VR ROE module featured 18.

A group of six experts, comprising three nursing professors and three clinical nurses, validated the EFMPE content. One clinical nurse had over ten years of clinical experience and two years in educational roles within a healthcare institution, while the other two had more than seven years of combined clinical and educational experience. Experts reviewed educational materials and demonstration videos of the VR ROE practices, assessing content and timing validity. Based on expert feedback, the EFMPE was revised to include additional explanations of complex terminology, removal of peer evaluation components, and modification of learning objectives. The final version of the EFMPE is presented in

Table 1.

The study population consisted of fourth-year nursing students who had gained experience in hospital environments and patient safety-related nursing through clinical practicums. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) nursing students in their fourth year as of 2024, and (2) current enrollment at the university. Students without clinical experience were excluded to prevent potential confusion, as the VR-simulated hospital room included specific items selected for learning purposes. Additionally, students who had taken a leave of absence during a previous semester or who had previously participated in a VR learning program within the nursing curriculum were excluded. This study determined a minimum of 13 participants per group was necessary for preliminary evaluation based on Hertzog’s suggestion (2008) that 10 to 40 subjects per group are sufficient for preliminary studies [

23], and a previous nursing study that reported positive outcomes with 13 subjects [

24]. With an anticipated dropout rate of 20%, the planned recruitment was 16 participants per group, totaling 32.

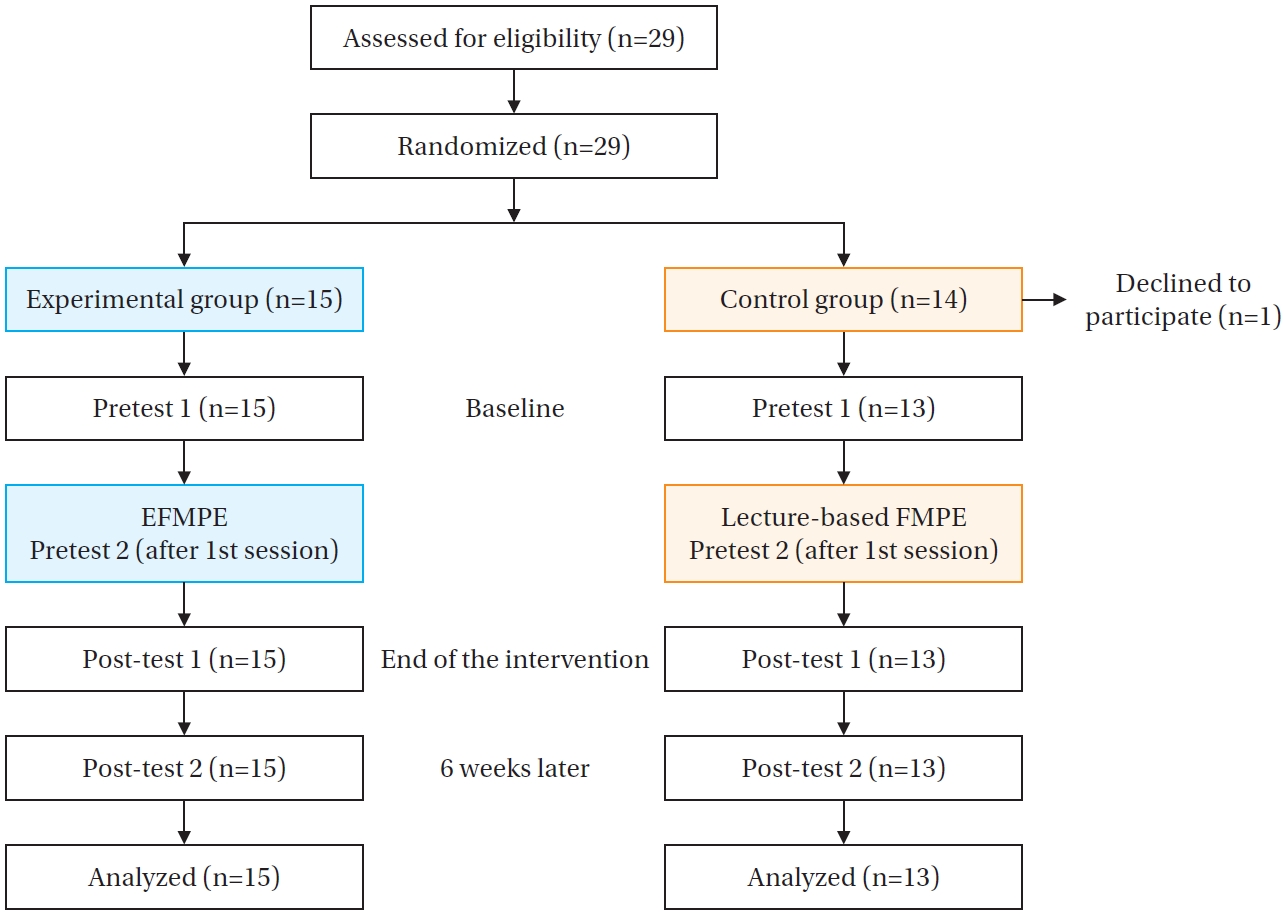

Participants were recruited from Kosin University in Busan, Korea. Recruitment was facilitated through announcements posted on an online bulletin board and social networking services specifically targeted at fourth-year students. The researcher assigned numbers to all 29 consenting participants in the order they provided informed consent, and these numbers were entered into a ‘

Random Group Assignment’ application. Participants were randomly assigned to either the experimental group (n=15) or the control group (n=14) using simple randomization. Group allocations were finalized after recruitment, and participants were informed of their group assignments immediately prior to pretest 1. One control group participant withdrew before pretest 1 due to health issues, resulting in 15 participants in the experimental group and 13 in the control group (

Figure 2).

Safety control confidence was assessed using a seven-item questionnaire developed by Anderson et al. [

15] and translated into Korean by Chung [

25]. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=completely disagree, 5=completely agree), with higher scores indicating greater safety control confidence. Cronbach’s alpha for the questionnaire was .85 in Chung’s study, and ranged from .78 to .88 across the three measurement points in this study.

Course interest was measured using the Course Interest Survey (CIS), originally developed by Keller in 1987 [

19]. This study employed a Korean version adapted by Kim [

26] with the original author’s permission. This adapted CIS comprises 20 items, reduced from the original 34, covering four subdomains: attention (5 items), confidence (3 items), relevance (5 items), and satisfaction (7 items). Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1=not true, 5=very true), with higher scores reflecting greater learning interest. The original instrument had a Cronbach’s alpha of .95, while this study’s adapted CIS had a Cronbach’s alpha of .92 at pre-measurement and .96 at post-measurement.

The EFMPE intervention was conducted from February 1 to 6, 2024, consisting of six 2-hour sessions. Session 1, common to both experimental and control groups, provided foundational knowledge about patient safety and medical errors through lectures. Pretest 1, measuring safety control confidence and general participant characteristics, occurred before session 1. Pretest 2, measuring course interest, was administered immediately following session 1.

Sessions 2 and 4 covered fall prevention and medication error prevention knowledge through lectures and scenario reviews. VR ROE practices were conducted in sessions 3 and 5, representing the CE stage of Kolb’s experiential learning cycle, with session 3 focusing on nursing care for a right total knee replacement patient and session 5 addressing a laparoscopic myomectomy patient. Each VR ROE session included pre-briefing, two practice rounds, and debriefing. In the first round, students set up error situations for opposing teams; in the second round, they corrected the errors. RO was incorporated through individual reflection journals, and AC was fostered through team discussions and evaluations regarding patient safety and error prevention during debriefings.

Session 6 summarized educational content and focused on post-incident patient safety management. This aligned with the AE stage as students applied learned concepts to develop checklists for preventing falls and medication errors. Post-test 1, assessing safety control confidence and course interest, was conducted immediately after all sessions. Post-test 2, exclusively assessing safety control confidence, occurred 6 weeks later because the CIS targets specific content unsuitable for long-term evaluation. The 6-week interval was chosen based on Kosin University’s curriculum structure to ensure uniformity in students’ experiences. After the intervention, students were split into two groups, each alternating between 3 weeks of clinical practicum and 3 weeks of on-campus practicum. Random group assignment ensured standardized conditions, and post-test 2 was scheduled to control potential confounding variables and ensure standardized conditions across all participants.

The control group received identical educational content via lectures without VR ROE practices. Separate schedules were arranged for experimental and control groups starting from session 2 to prevent information diffusion.

7. Ethical Considerations

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Health System, Severance Hospital (approval number: 4-2023-1498), nursing students who expressed interest in participating were recruited on a voluntary basis. The researcher provided detailed explanations regarding the study’s objectives, procedures, potential benefits, and risks. Participants were assured that their personal information would remain confidential and that collected data would not be used for any purpose other than the study. All participants provided written informed consent prior to their participation in the research.

To prevent any confusion between participation in this study and regular coursework, especially if professor names appeared in recruitment announcements, this research was conducted exclusively with students from Kosin University in Busan, ensuring that none of the research team members were affiliated with this university. The informed consent explicitly clarified that the study was independent of the students’ curriculum and assured participants that their involvement would remain confidential and would not be disclosed to their professors. Additionally, to uphold ethical standards for the control group, these participants were informed that they could receive extra opportunities to practice fall and medication error situations using the VR ROE modules after the study concluded if they desired.

8. Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations, summarized participant characteristics. Mean values and standard deviations for all measured variables were reported. Group homogeneity was assessed using independent t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests. Generalized Estimating Equations (GEEs) evaluated outcome measure changes over time.

Blinding in data analysis was maintained by having a research assistant, uninvolved in intervention delivery, enter the collected data into a computer file. Data were secured, anonymized, and then provided to the researcher for statistical analysis.

RESULTS

1. General Characteristics and Homogeneity between Groups

Data from 15 participants in the experimental group and 13 participants in the control group were collected and analyzed.

Table 2 summarizes the participants’ general characteristics and presents the homogeneity test results between groups. No statistically significant differences in participants’ general characteristics were observed between the experimental and control groups.

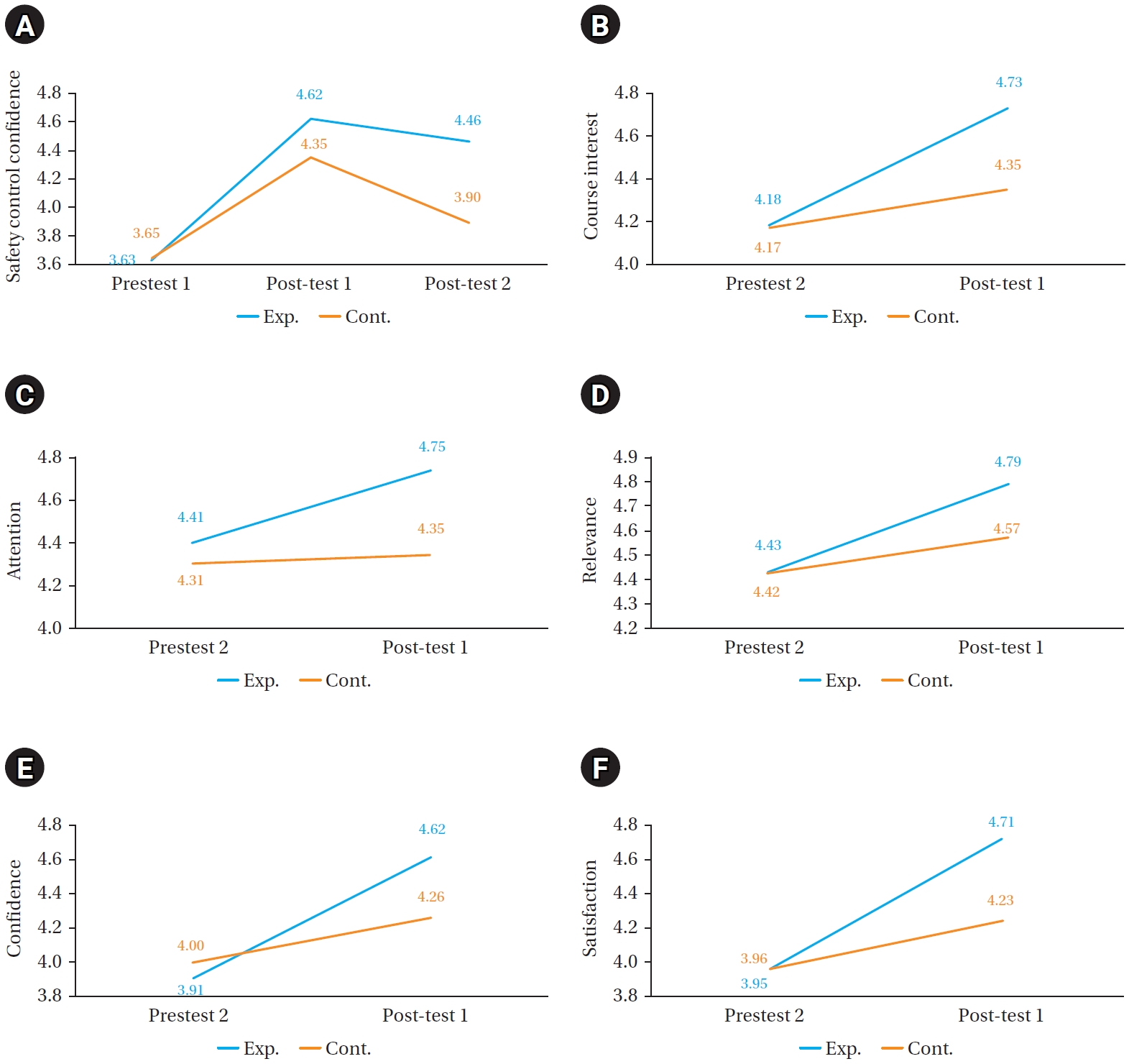

Safety control confidence was assessed at three time points for both groups: pretest 1, post-test 1, and post-test 2. The experimental group exhibited higher safety control confidence than the control group at both post-test 1 and post-test 2, as illustrated in

Table 3. The GEE analysis showed a statistically significant interaction between group and time regarding changes in safety control confidence (Wald

χ2=13.21,

p<.001), thereby supporting Hypothesis 1 (

Table 3). Course interest was measured twice for both groups: at pretest 2 and post-test 1. Both groups experienced an increase in course interest following the intervention. GEE analysis indicated a statistically significant greater increase in course interest for the experimental group compared to the control group over time (Wald

χ2=10.64,

p=.001), supporting Hypothesis 2 (

Table 3).

Upon examining the subdomains of course interest, post-test 1 scores were consistently higher than pretest 2 scores for both groups. GEE analysis indicated that differences between groups over time were not significant for the attention (Wald

χ2=3.34,

p=.068) and relevance (Wald

χ2=1.75,

p=.186) subdomains. However, differences were significant for the confidence (Wald

χ2=6.09,

p=.014) and satisfaction (Wald

χ2=7.95,

p=.005) subdomains. Changes in variables between the two groups are visually represented in the graph provided in

Appendix 1.

DISCUSSION

This study developed and applied the EFMPE, enhancing experiential learning with VR and ROE, among nursing students. Its effectiveness was demonstrated through significant improvements in safety control confidence and course interest.

Both groups in this study showed immediate increases in safety control confidence following the intervention; however, only the experimental group maintained elevated levels 6 weeks later, underscoring the intervention’s lasting impact. Although research on VR-based ROE patient safety programs specifically for nursing students is limited, our results align with prior experiential learning studies reporting increased safety control confidence [

14,

27]. Kim and Chun [

27] research team provided nursing students a VR environment simulating urinary retention in surgical patients, significantly increasing students’ safety control confidence by offering highly immersive experiences. Similarly, Jung et al. [

14] introduced nursing students to various simulated errors—such as medication errors, fall risks, procedural safety issues, and hospital-associated infections—learning error recognition in small teams. They concluded that exposure to diverse error scenarios boosted students’ safety control confidence. Thus, VR and ROE-based experiential learning environments has the potential to effectively increase nursing students’ safety control confidence, though further research is necessary for definitive evidence.

Experiential learning is widely acknowledged for its sustained impact on healthcare professionals’ competencies [

7]. For example, Torkshavand and colleagues demonstrated long-term competency improvements related to elderly patient care through simulation-based learning, where students directly experienced sensory impairments using special equipment [

28]. These outcomes align with our findings, underscoring experiential learning’s lasting educational effects. According to experiential learning theory, learners continuously restructure their knowledge through a cyclic process of experiencing, reflecting, conceptualizing, and experimenting [

8]. In contrast, lecture-based approaches, though informative, typically involve passive student participation, limiting long-term knowledge retention [

29]. After the EFMPE, students may encounter environments where fall and medication errors could occur during their scheduled clinical and on-campus practicums. These repeated experiences would prompt students to recall and reflect on the learning content from the EFMPE, engaging in reflection and AC. This ongoing learning cycle would be expected to contribute to the retention and enhancement of their knowledge, supporting their development of sustained fall and medication error prevention competencies.

In this study, course interest increased significantly in the experimental group compared to the control group, with notable improvements particularly in the confidence and satisfaction subdomains. Course interest—comprising attention, relevance, confidence, and satisfaction—motivates ongoing learning [

19].

In the current study, confidence in course interest increased in the experimental group after the intervention compared to the control group. Confidence, which contributes to course interest, is defined as the extent to which learners believe they can control their own learning [

19,

26]. This belief is strengthened by accumulating successful experiences [

26]. Previous studies employing pre-learning activities have successfully boosted learner confidence [

30,

31]. For instance, a neonatal resuscitation program that used preliminary online videos enhanced student confidence, subsequently improving hands-on performance [

30]. Similarly, preparatory mobile learning assignments on communicating with foreign patients significantly increased students’ classroom engagement by improving their learning confidence [

31]. In the current study, comprehensive theoretical preparation enabled students to successfully engage in VR ROE practices, likely enhancing their sense of achievement and subsequent learning confidence.

Satisfaction, a component of course interest, also significantly improved in the experimental group. Satisfaction rewards learning achievement through intrinsic and extrinsic reinforcement [

19,

26]. During VR practice sessions, supportive instructor feedback, such as “You saved the patient,” positively reinforced students' actions aligned with learning objectives, thus fostering intrinsic motivation [

32]. In team debriefings, recognition from peers and instructors for correctly identifying errors further bolstered student satisfaction and positive emotions associated with learning, enhancing motivation [

33,

34]. Previous research involving task-centered virtual learning environments reported positive correlations between satisfaction and realistic task simulations [

32]. Interactive methods such as peer recognition and collaboration have also been recognized as effective strategies for boosting academic motivation [

35]. Our findings suggest that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivational factors contributed significantly to student satisfaction in course interest.

This study has several limitations. First, participants were recruited from a single university in Korea, potentially limiting the generalizability of findings to other institutions or regions. Second, the study exclusively measured safety control confidence and course interest. Future research should incorporate additional outcome measures—such as knowledge, skills, and attitudes related to falls and medication error management—for a comprehensive evaluation of educational effectiveness. Lastly, the study utilized only quantitative measures, with findings interpreted through experiential learning theory. Incorporating qualitative data, such as open-ended responses, could provide deeper insights into the observed improvements in safety control confidence and course interest among students in the experimental group.

This study is significant as it successfully implemented experiential learning by integrating VR technology and the ROE approach into the EFMPE. These methods offered students structured opportunities to engage safely with patient safety incidents, which are otherwise challenging to replicate in actual clinical environments. Additionally, this study contributes valuable evidence supporting the efficacy of experiential learning theory. By demonstrating that experiential learning-based nursing education programs can significantly enhance both safety control confidence and course interest, these findings may encourage wider adoption of experiential learning strategies in nursing education.

The notable improvements observed in this preliminary study regarding safety control confidence and course interest highlight the potential of the EFMPE for enhancing nursing students’ patient safety competencies. The EFMPE could effectively serve as a structured educational resource, assisting students in developing essential skills for preventing patient safety incidents and reducing preventable errors in clinical settings. Future simulations should incorporate clinically relevant scenarios, both common and rare, such as patient falls during transfers or medication administration errors. Diversifying case scenarios and integrating realistic clinical situations would further enhance the educational value and comprehensiveness of the EFMPE as a patient safety training tool.

CONCLUSION

The EFMPE, grounded in Kolb’s experiential learning theory, demonstrated potential for improving nursing students' safety control confidence and course interest. Further research is recommended to validate these findings by assessing additional competencies directly related to fall and medication error prevention, employing varied outcome measures. Developing realistic clinical simulation scenarios and expanding the curriculum to cover broader patient safety topics—such as infection control, medical device management, and documentation practices—may support the comprehensive incorporation of patient safety education into nursing curricula.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and/or design acquisition - HP, JL, EKC, SEL, EBY, and YL; analysis - HP; interpretation of the data - HP and JL; and drafting or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content - HP, JL, EKC, SEL, EBY, and YL.

-

FUNDING

The study was conducted with the support of the 2022 Health Fellowship Foundation. The author Hyeran Park received a scholarship from Brain Korea 21 FOUR Project funded by National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea, Yonsei University College of Nursing.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of all participants in data collection. We would like to express our gratitude to Professor Kijun Song for his valuable statistical guidance and support, which greatly contributed to the completion of this study. This article is a revision of the first author’s doctoral dissertation from Yonsei University.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data can be obtained from the corresponding authors.

Figure 1.Screenshots of virtual reality (VR) room of errors (ROE) practices: (A) lowering bedside rails in the fall VR ROE practice, (B) tilting a container to spill water on the floor in the fall VR ROE practice, (C) misaligning a 3-way valve in the medication VR ROE practice, (D) mislabeling syringes in the medication VR ROE practice.

Figure 2.Flow diagram of the allocation. EFMPE=experiential learning-based fall and medication error prevention education; FMPE=fall and medication error prevention education.

Table 1.Final Version of the EFMPE

|

Session |

Title |

Contents |

Delivery methods |

Time |

|

1 |

Understanding of medical errors |

Definition of patient safety and related concepts |

Lecture |

2 |

|

Risk factors and intervention for preventing medical errors |

|

2 |

EFPE (1) |

Definition, risk factors and preventive interventions for falls |

Lecture |

2 |

|

Review of Rt. TKR patient information on preventable fall risk |

Scenario review |

|

1) Individually searching the fall risks in the case |

|

|

2) Presenting the identified fall risks individually |

|

|

|

3) Discussing and determining the presented risk factors by all class members |

|

|

|

3 |

EFPE (2) |

Fall VR ROE |

Simulation |

2 |

|

- Pre-briefing: Listing the errors to be implemented in the VR ROE practice |

|

|

|

- Practice (1): Setting up the errors for the opposing team |

|

|

|

- Practice (2): Correcting the errors set by the opposing team |

|

|

|

- Individual reflection: Reviewing the actions performed |

|

|

|

- Team reflection: Discussing and evaluating actions in terms of patient risk |

|

|

|

- Debriefing and discussion: Assessing the significance of risks and anticipating their application in the clinical setting |

|

|

|

4 |

EMPE (1) |

Definition, risk factors, and preventive interventions for medication errors |

Lecture |

2 |

|

Review of laparoscopic myomectomy patient information on preventable medication errors |

Scenario review |

|

1) Individually searching the medication error risks in the case |

|

|

|

2) Presenting the identified medication error risks individually |

|

|

|

3) Discussing and determining the presented risk factors by all class members |

|

|

|

5 |

EMPE (2) |

Medication VR ROE |

Simulation |

2 |

|

- Pre-briefing: Listing the errors to be applied in the VR ROE practice |

|

|

|

- Practice (1): Setting up the errors for the opposing team |

|

|

|

- Practice (2): Correcting the errors set by the opposing team |

|

|

|

- Individual reflection: Reviewing the actions performed |

|

|

|

- Team reflection: Discussing and evaluating actions in terms of patient risk |

|

|

|

- Debriefing and discussion: Assessing the significance of risks and anticipating their application in the clinical setting |

|

|

|

6 |

Post patient safety incident management |

Summarizing the entire content of the education and learning the process after patient safety incidents |

Lecture |

2 |

|

Creating checklists to prevent fall |

Activity |

|

Creating checklists to prevent medication errors |

Activity |

Table 2.General Characteristics of Participants and Homogeneity between Groups at Baseline (N=28)

|

Variables |

Categories |

n (%) or M ± SD |

t/χ2

|

p

|

|

Exp. (n=15) |

Cont. (n=13) |

|

Age (year) |

|

21.5±0.99 |

22.2±1.63 |

–1.24 |

.226 |

|

Sex |

Female |

14 (93.3) |

10 (76.9) |

|

.311 |

|

Male |

1 (6.7) |

3 (23.1) |

|

|

|

GPA in last semester |

≥2.5 to <3.0 |

2 (13.3) |

2 (15.4) |

|

>.99 |

|

≥3.0 to <3.5 |

4 (26.7) |

3 (23.1) |

|

|

|

≥3.5 to <4.0 |

7 (46.7) |

6 (46.2) |

|

|

|

≥4.0 |

2 (13.3) |

2 (15.4) |

|

|

|

Satisfaction in major†

|

|

3.47±0.74 |

3.62±0.96 |

–0.46 |

.648 |

|

Satisfaction in clinical practicum†

|

|

3.33±0.82 |

3.23±1.09 |

0.28 |

.779 |

|

Satisfaction in on-campus practicum†

|

|

3.53±0.83 |

3.38±0.77 |

0.49 |

.630 |

Table 3.Changes in Safety Control Confidence and Course Interest between Groups (N=28)

|

Variables |

M±SD |

Parameters |

Regression coefficient |

SE |

Wald χ2

|

p

|

|

Pretest†

|

Post-test 1 |

Post-test 2 |

|

Safety control confidence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exp. (n=15) |

3.63±0.47 |

4.62±0.38 |

4.46±0.37 |

Group (ref. Cont.) |

–0.02 |

0.19 |

0.01 |

.918 |

|

Cont. (n=13) |

3.65±0.57 |

4.35±0.38 |

3.90±0.42 |

Time 1 (ref. Pretest) |

0.70 |

0.20 |

12.09 |

<.001 |

|

|

|

|

Time 2 (ref. Pretest) |

0.25 |

0.09 |

8.77 |

.003 |

|

|

|

|

Group* Time 1 (ref. Cont. * Pretest) |

0.29 |

0.25 |

1.30 |

. 255 |

|

|

|

|

Group* Time 2 (ref. Cont. * Pretest) |

0.58 |

0.16 |

13.21 |

<.001 |

|

Course interest |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exp. (n=15) |

4.18±0.47 |

4.73±0.33 |

- |

Group (ref. Cont.) |

0.02 |

0.17 |

0.01 |

.932 |

|

Cont. (n=13) |

4.17±0.48 |

4.35±0.54 |

- |

Time 1 (ref. Pretest) |

0.19 |

0.06 |

8.97 |

.003 |

|

|

|

|

Group* Time 1 (ref. Cont. * Pretest) |

0.36 |

0.11 |

10.64 |

.001 |

|

Attention |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exp. (n=15) |

4.41±0.50 |

4.75±0.73 |

- |

Group (ref. Cont.) |

0.11 |

0.23 |

0.21 |

.648 |

|

Cont. (n=13) |

4.31±0.35 |

4.35±0.68 |

- |

Time 1 (ref. Pretest) |

0.05 |

0.14 |

0.11 |

.741 |

|

|

|

|

Group* Time 1 (ref. Cont. * Pretest) |

0.29 |

0.16 |

3.34 |

.068 |

|

Relevance |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exp. (n=15) |

4.43±0.53 |

4.79±0.56 |

- |

Group (ref. Cont.) |

0.01 |

0.20 |

0.00 |

.955 |

|

Cont. (n=13) |

4.42±0.38 |

4.57±0.42 |

- |

Time 1 (ref. Pretest) |

0.15 |

0.11 |

1.84 |

.175 |

|

|

|

|

Group* Time 1 (ref. Cont. * Pretest) |

0.21 |

0.16 |

1.75 |

.186 |

|

Confidence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exp. (n=15) |

3.91±0.60 |

4.62±0.59 |

- |

Group (ref. Cont.) |

–0.09 |

0.22 |

0.17 |

.682 |

|

Cont. (n=13) |

4.00±0.40 |

4.26±0.60 |

- |

Time 1 (ref. Pretest) |

0.26 |

0.07 |

12.04 |

.001 |

|

|

|

|

Group* Time 1 (ref. Cont. * Pretest) |

0.46 |

0.18 |

6.09 |

.014 |

|

Satisfaction |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Exp. (n=15) |

3.95±0.55 |

4.71±0.45 |

- |

Group (ref. Cont.) |

0.00 |

0.18 |

0.00 |

.984 |

|

Cont. (n=13) |

3.96±0.37 |

4.23±0.59 |

- |

Time 1 (ref. Pretest) |

0.28 |

0.12 |

5.08 |

.024 |

|

|

|

|

Group* Time 1 (ref. Cont. * Pretest) |

0.49 |

0.17 |

7.95 |

.005 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Korea Institute for Healthcare Accreditation. Patient safety statistics annual report [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Patient Safety Reporting & Learning System; 2024 [cited 2024 December 15]. Available from: https://www.kops.or.kr/portal/board/statAnlrpt/boardDetail.do

- 2. Cochran L, Foley P. Pursuing zero harm from patient falls: one organization's initiatives along the way. Nurs Manage. 2022;53(11):24-33. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NUMA.0000891464.12616.70

- 3. Elliott RA, Camacho E, Jankovic D, Sculpher MJ, Faria R. Economic analysis of the prevalence and clinical and economic burden of medication error in England. BMJ Qual Saf. 2021;30(2):96-105. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2019-010206

- 4. Van Slambrouck L, Verschueren R, Seys D, Bruyneel L, Panella M, Vanhaecht K. Second victims among baccalaureate nursing students in the aftermath of a patient safety incident: an exploratory cross-sectional study. J Prof Nurs. 2021;37(4):765-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2021.04.010

- 5. Lee Y, Choi B, An S. Nursing student's cinical practice experience. J Humanit Soc Sci. 2021;12(2):531-46. https://doi.org/10.22143/HSS21.12.2.38

- 6. Murray R. An overview of experiential learning in nursing education. Adv Soc Sci Res J. 2018;5(1):1-6. https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.51.4102

- 7. Nurunnabi AS, Rahim R, Alo D, Mamun AA, Kaiser AM, Mohammad T, et al. Experiential learning in clinical education guided by the Kolb’s experiential learning theory. Int J Hum Health Sci. 2022;6(2):155-60. https://doi.org/10.31344/ijhhs.v6i2.438

- 8. Kolb DA. Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984.

- 9. Uppor W, Klunklin A, Viseskul N, Skulphan S. Effects of experiential learning simulation-based learning program on clinical judgment among obstetric nursing students. Clin Simul Nurs. 2024;92:101553. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2024.101553

- 10. Chang CY, Kao CH, Hwang GJ, Lin FH. From experiencing to critical thinking: a contextual game-based learning approach to improving nursing students’ performance in electrocardiogram training. Educ Technol Res Dev. 2020;68(3):1225-45. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09723-x

- 11. Choi J, Thompson CE, Choi J, Waddill CB, Choi S. Effectiveness of immersive virtual reality in nursing education: systematic review. Nurse Educ. 2022;47(3):E57-61. https://doi.org/10.1097/NNE.0000000000001117

- 12. Shorey S, Ng ED. The use of virtual reality simulation among nursing students and registered nurses: a systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;98:104662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104662

- 13. Lee SE, Repsha C, Seo WJ, Lee SH, Dahinten VS. Room of horrors simulation in healthcare education: a systematic review. Nurse Educ Today. 2023;126:105824. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2023.105824

- 14. Jung SY, Kim HJ, Lee EK, Park JH. Effects of “room of errors” simulation education for nursing students on patient safety management behavior intention and confidence in performance. J Korean Soc Simul Nurs. 2023;11(2):107-20. https://doi.org/10.17333/JKSSN.2023.11.2.107

- 15. Anderson L, Chen PY, Finlinson S, Krauss AD, Huang YH. Roles of safety control and supervisory support in work safety. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology; 2004 May 27-30; Chicago, IL.

- 16. Gottlieb M, Chan TM, Zaver F, Ellaway R. Confidence-competence alignment and the role of self-confidence in medical education: a conceptual review. Med Educ. 2022;56(1):37-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14592

- 17. Kalsoom Z, Victor G, Virtanen H, Sultana N. What really matters for patient safety: correlation of nurse competence with international patient safety goals. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2023;28(3):108-15. https://doi.org/10.1177/25160435221133955

- 18. Kim K, Mun MY. Influence of confidence in performance of patient safety management and clarity of communication on behavior of patient safety management in nursing students. J Learn Cent Curric Instr. 2023;23(3):85-95. https://doi.org/10.22251/jlcci.2023.23.3.85

- 19. Keller JM. Motivational design for learning and performance. New York: Springer; 2010.

- 20. Kong Y. The role of experiential learning on students' motivation and classroom engagement. Front Psychol. 2021;12:771272. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.771272

- 21. Morris TH. Experiential learning: a systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interact Learn Environ. 2020;28(8):1064-77. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2019.1570279

- 22. Branch RM, Kopcha TJ. Instructional design models. In: Spector JM, Merrill MD, Elen J, Bishop MJ, editors. Handbook of research on educational communications and technology. New York: Springer; 2014. p. 77-87.

- 23. Hertzog MA. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31(2):180-91. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20247

- 24. Delaney MC. Caring for the caregivers: Evaluation of the effect of an eight-week pilot mindful self-compassion (MSC) training program on nurses' compassion fatigue and resilience. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207261. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207261

- 25. Chung SK. A structural model of safety climate and safety compliance of hospital organization employees [dissertation]. Seoul: Yonsei University; 2010.

- 26. Kim MR. Validity verification of ARCS evaluation models for promoting university students' learning motivation. J Korea Contents Assoc. 2017;17(12):77-91. https://doi.org/10.5392/JKCA.2017.17.12.077

- 27. Kim HY, Chun J. Effects of a patient experience-based virtual reality blended learning program on nursing students. Comput Inform Nurs. 2022;40(7):438-46. https://doi.org/10.1097/CIN.0000000000000817

- 28. Torkshavand G, Khatiban M, Soltanian AR. Simulation-based learning to enhance students' knowledge and skills in educating older patients. Nurse Educ Pract. 2020;42:102678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2019.102678

- 29. Woodhouse J. Strategies for healthcare education: how to teach in the 21st century. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2019.

- 30. Yang SY, Oh YH. The effects of neonatal resuscitation gamification program using immersive virtual reality: a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;117:105464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105464

- 31. Zhang D, Zhang J, Cao M, Zhu Y, Yang G. Testing the effectiveness of motivation-based teaching in Nursing English course: a quasi-experimental study. Nurse Educ Today. 2023;122:105723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2023.105723

- 32. Zwart DP, Goei SL, Van Luit JE, Noroozi O. Nursing students’ satisfaction with the instructional design of a computer-based virtual learning environment for mathematical medication learning. Interact Learn Environ. 2022;31(10):7392-407. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2071946

- 33. Liu M. Exploring the motivation-engagement link: the moderating role of positive emotion. J Psychol Lang Learn. 2022;4(1):e415022. https://doi.org/10.52598/jpll/4/1/3

- 34. Plunkett A. Embracing excellence in healthcare: the role of positive feedback. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2022;107(5):351-4. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2020-320882

- 35. Saeedi M, Ghafouri R, Tehrani FJ, Abedini Z. The effects of teaching methods on academic motivation in nursing students: a systematic review. J Educ Health Promot. 2021;10:271. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_1070_20

Appendices

Appendix 1.

- Changes in variables between two groups: (A) safety control confidence, (B) course interest, (C) attention, (D) relevance, (E) confidence, and (F) satisfaction. (C–F) Subdomains of course interest. Cont.=control group; Exp.=experimental group.