Abstract

-

Purpose

This study analyzed nursing students’ guided reflective journals following simulation-based practice using standardized patients for the initial care of older adults experiencing falls. It aimed to provide a deeper understanding of how changes in students’ thinking occurred through the learning experience and to describe their levels of reflection.

-

Methods

An eight-hour simulation-based education program was implemented during a geriatric clinical practicum. The program consisted of orientation, pre-learning activities, simulation practice, and a wrap-up session. Reflective journals from 53 third-year nursing students were analyzed using qualitative content analysis.

-

Results

Fifty-three third-year nursing students participated and submitted reflective journals. Three categories emerged from the analysis: “preparing for simulation-based practice,” which involved students setting care plans and employing observation; (2) “experiencing patient fall management through simulation-based practice,” where students actively engaged in realistic fall management scenarios; and (3) “critical reflection after simulation-based practice,” encompassing students’ acquisition of new insights and their personal growth. In the first category, students prepared for patient encounters by developing care plans and conducting observations. The second category highlighted realistic fall management scenarios utilizing standardized patients. The third category focused on personal growth through critical reflection. In the 53 reflective journals (185,021 words), level 3 reflections accounted for 31.6% of the content, while level 5, the highest reflection level, comprised only 8.6%.

-

Conclusion

Post-simulation reflective journaling stimulated critical thinking and self-assessment, enabling nursing students to analyze and reflect deeply on clinical practices. This process reinforced their knowledge base and behavioral foundations essential for clinical practice.

-

Key Words: Accidental falls; Cognitive reflection; Nursing; Patient simulation; Qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Falls are the second most common safety-related accidents occurring in healthcare facilities [

1], with older adults at significantly higher risk than other age groups. Falls can lead to severe complications, such as cerebral hemorrhage, fractures, and even death [

1]. This underscores the importance of fall prevention education within geriatric nursing practicums, as well as the necessity for timely and appropriate evaluation, intervention, and reporting of a patient’s condition immediately following a fall [

2]. Despite the high incidence of falls in healthcare settings [

3], their unpredictability makes it challenging for nursing students to acquire real-world experience managing such incidents during clinical practice [

4]. Consequently, most educational programs tend to focus primarily on fall prevention rather than the management of actual fall incidents.

Growing difficulties in placing nursing students in clinical practice—particularly due to restrictions imposed by infectious diseases such as coronavirus disease 2019 in recent years—have heightened the need for alternative methods of clinical education [

5]. These alternatives are vital not only for fulfilling students’ clinical experience requirements but also for providing training in managing fall incidents, which students might rarely encounter during traditional clinical placements [

6].

Simulation-based education has emerged as an effective pedagogical approach, fostering students’ problem-solving abilities and coping skills through realistic clinical scenarios [

7]. Specifically, simulation-based learning using standardized patients (SPs) has been demonstrated to positively influence nursing students’ communication skills, self-efficacy, and knowledge acquisition, while also providing a highly realistic clinical experience [

8,

9]. Such education is valuable because it allows students to extend their learning beyond theoretical knowledge, aiding in the translation of simulated experiences into practical clinical skills [

10,

11].

Reflection is a crucial component of learning, especially in nursing education, where it facilitates the development of clinical reasoning and judgment. The five levels of reflection—reporting, responding, relating, reasoning, and reconstructing—progressively move from descriptive to analytical, providing a structured framework to enhance reflective practice [

12]. At the reporting level, the writer provides a descriptive account of a situation, event, or issue. The responding level involves expressing emotional or personal reactions to the experience. At the relating level, the writer analyzes the situation using a theoretical framework, integrating both personal and academic perspectives. The reasoning level entails critically examining, exploring, or deeply explaining the issue. Finally, at the reconstructing level, the writer synthesizes insights to formulate conclusions and develop a reasoned plan for future actions [

3,

12]. These levels guide students toward meaningful reflection and support the integration of theoretical knowledge with practical skills. Furthermore, analyzing reflection levels helps educators identify gaps in students’ thinking, allowing them to tailor educational strategies to enhance clinical nursing skills [

3,

13].

To facilitate the transfer of learning—that is, applying knowledge and skills gained through simulation education into clinical settings—students and faculty must engage in reflection, provide feedback, and discuss their experiences during simulations. This process, known as debriefing [

14], helps structure these experiences meaningfully as the final step of simulation-based education [

15]. Debriefing encourages reflection, enabling students to transfer and integrate insights, clinical competencies, and knowledge gained through simulation into real-world clinical practice [

14,

15].

The ultimate goal of reflection is to encourage reflective thinking, often achieved through journal writing, which allows learners to articulate and organize their thoughts regarding clinical experiences. This process stimulates critical thinking and enhances clinical judgment [

5,

16]. Reflective writing enables learners to systematically review and analyze their practice over time, thereby developing problem-solving skills and reinforcing learning through self-directed efforts [

16,

17]. Guided reflective writing, as an active learning strategy, can enhance educational outcomes and improve clinical judgment in patient care [

5].

In this study, we implemented a simulation-based educational curriculum on the initial management of falls in older adults using SPs and collected guided reflective journals from nursing students. We analyzed these reflective journals to explore the students’ reflective thinking processes. The aim of this study was to provide an in-depth understanding of how students’ reflective thinking evolves through their experiences managing falls in older adults using SPs, thus providing foundational insights for advancing simulation-based education in nursing.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This qualitative study employed content analysis to explore nursing students’ guided reflective journals submitted after their participation in simulation-based training.

2. Participants and Settings

1) Participants

Fifty-six third-year nursing students from a university in Wonju City were recruited using convenience sampling. Inclusion criteria included students enrolled in the Geriatric Nursing Practicum course during their second semester, who participated in a simulation-based training program focused on early fall management as part of their clinical education (

Table 1), and who agreed to participate in the study. The simulation training occurred between October 12 and December 4, 2020, involving a total of 56 students. Data extraction occurred from March 25 to April 7, 2021, with 53 students consenting to participate in the study; three students who were on leave were excluded.

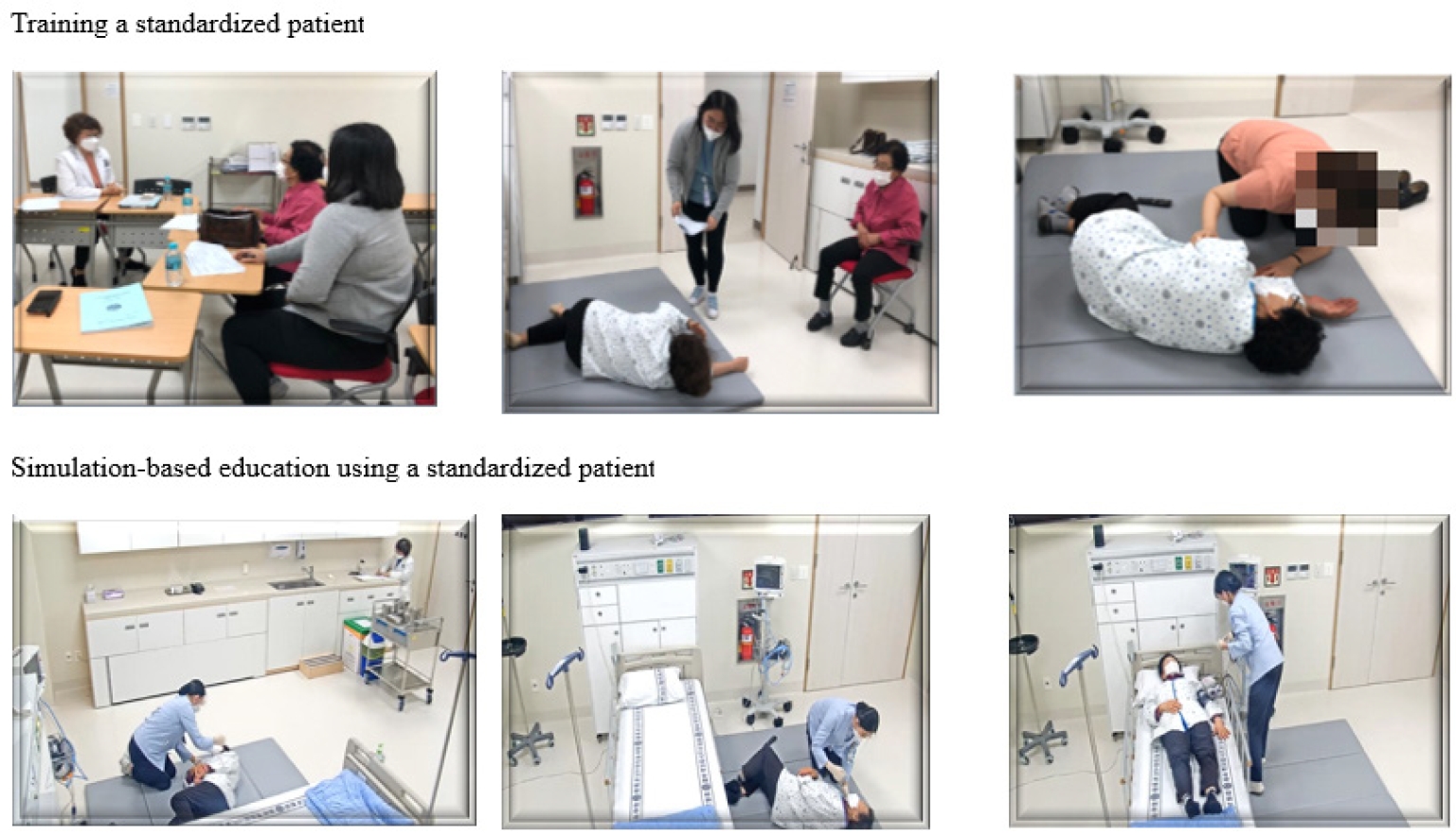

2) Simulation-based education for early fall management

The research team, including experts in simulation-based education and a doctoral student with eight years of geriatric care experience, developed a preliminary simulation scenario involving fall management with SPs. This initial scenario was reviewed by a nursing professor and a clinical expert from a long-term care facility.

The scenario began with a resident who had fallen from a bed while attempting to retrieve a TV remote control from the floor. In this scenario, the student nurse was tasked with assessing the patient, moving the patient to a safe location, re-evaluating the patient’s condition, and reporting the situation to a physician. The scenario development drew upon previous studies on fall management [

2,

18], evidence-based practice guidelines from the Hospital Nurses Association [

19], and hospital-based fall management algorithms [

20]. It was created in alignment with simulation education standards [

21].

To increase realism, an SP in her 70s, closely resembling the patient described in the scenario, was recruited. The researcher provided the SP with verbal explanations about her role, clarified the training objectives, and reintroduced the scenario with detailed written instructions. Mock training was carried out in the same clinical practice room where the simulation-based education sessions took place (

Appendix 1).

Students were divided into groups of two or three. The program consisted of four primary components: orientation, pre-learning, simulation, and journal writing. After completing pre-learning activities, students participated in the simulation practice in groups of two or three. Following pre-briefing, participants were divided into three groups (groups 1, 2, and 3). Before the simulation practice, an instructor provided an orientation explaining the self-study content and simulation procedures. The pre-learning session also included a review of the simulation room, the equipment necessary for caring for SPs, and observation areas for students watching other teams perform (

Table 1).

Due to limitations in instructor availability, space, and resources, each group’s simulation practice was observed by the other groups through a one-way mirror in the control room, either before or after their own session. Observing groups did not receive guidance. After completing the simulation, participants had time to reflect quietly on their practice before participating in structured debriefing sessions.

3. Data Collection

Semi-structured questions for guided reflective journaling were developed based on previous studies related to debriefing and reflective journaling [

15,

22]. The questions were classified into technical, analytical, and application-based categories, each corresponding to different reflection levels. Technical questions (e.g., “What was your experience using simulation-based training with SP?”) corresponded to level 1 (reporting) and level 2 (responding). Analytical questions (e.g., “Why did you perform that activity?”; "What did you think while observing other groups’ practice?”; “What did you think they did well in the simulation-based training?”) aligned with level 3 (relating) and level 4 (reasoning). Application-based questions (e.g., “How will you apply what you learned from this training to your clinical practice?”) related to level 5 (reconstructing). Students were given one day to complete their reflective journals, which they were instructed to upload to the learning management system (LMS). The reflective journals submitted by students ranged from three to four pages in length on A4-sized paper.

The Institutional Review Board of Wonju Severance Christian Hospital approved the data collection process before the start of the study (date of approval: 2021/03/24, No. CR321009). To ensure fairness, data extraction from the LMS began only in the semester following the simulation training. During the first semester of their fourth year, participants were informed about the purpose and methods of the study and provided consent for the use of the reflective journals they had previously submitted in the second semester of their third year. Students received an information sheet detailing the study’s objectives and procedures, and enrollment occurred only after obtaining their written consent.

To avoid potential disadvantages or unfair advantages, a research assistant explained the study’s purpose and methods during the semester following simulation-based training. Participants were assured that their reflective journals would not be graded. All identifying information, including names and student ID numbers, was removed to protect student privacy. The de-identified journals were downloaded from the LMS onto a USB drive and provided to two researchers for analysis.

5. Data Analysis

Two researchers analyzed the students’ reflective journals using qualitative content analysis, an objective technique involving deep immersion in the data to inductively derive themes and categories [

23]. The analysis was conducted using MAXQDA 2020 software (VERBI Software, Berlin, Germany) following Krippendorff’s six-step content analysis method: unitizing, sampling, recording/coding, reducing, abductively inferring, and narrating. The systematic analysis proceeded as follows: (1) Reflective journals were read repeatedly to grasp the overall meaning of the data. (2) The words, phrases, and sentences in the data were divided into units of analysis, and similar contents were merged and coded to identify meaningful statements. (3) Codes independently determined by two evaluators were compared, and discrepancies were reconciled by re-examining the raw data and engaging in further discussion to establish subcategories. (4) Subcategories were grouped by similarity to form more abstract categories. (5) Through abductive inference, underlying patterns and contextual meanings were identified, leading to a coherent synthesis of the findings. This process facilitated the extraction of meaningful insights aligned with the study’s objectives. (6) Categories were finalized after thorough discussions among the researchers. The researchers agreed that data saturation was reached, as no new codes emerged despite repeated analyses.

Levels of reflection were analyzed using MAXQDA software by examining word frequencies and percentage of text coverage. All researchers reviewed divergent interpretations, discussed the defining properties of each subcategory and category, and reached a consensus through group discussions.

6. Rigor of the Study

The rigor of this study was assured by addressing credibility, auditability, fittingness, and confirmability [

24]. To enhance credibility, semi-structured questions were utilized to help students vividly describe their practical experiences. Each researcher involved had prior experience in qualitative research and at least 7 years of experience with simulation and debriefing, thereby strengthening the credibility of data analysis and interpretation. Coding criteria were established in advance, and researchers independently conducted the coding analyses. Their results were subsequently exchanged, and ambiguous or problematic aspects were discussed collaboratively to refine and consolidate analysis outcomes through triangulation. This triangulation involved evaluation by a doctoral student with 8 years of geriatric nursing experience and two nursing professors. To ensure auditability, data analysis strictly followed the qualitative content analysis method, and raw data are presented transparently in the results. Fittingness, the measure of how applicable the study’s findings are to other subjects and contexts, was supported by providing detailed demographic information (gender, school year, and grade) of the 53 participants. This information allows for the findings to be relevant and transferable to similar educational contexts. Confirmability, which addresses the neutrality of the research findings, was strengthened by efforts to eliminate researcher bias as much as possible during data analysis. Analysis outcomes were repeatedly compared against study notes and reviewed across multiple rounds, with time intervals between each round to ensure objectivity. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist was used for the systematic reporting of qualitative study data [

25].

RESULTS

Fifty-three students submitted completed reflective journals; among them, 45 (84.9%) were women and eight (15.1%) were men. Qualitative content analysis yielded 617 meaningful statements, categorized into 10 subcategories under three main categories. The meaningful statements, along with their frequencies and percentages, are presented in

Table 2.

This phase involved gathering information through orientation and pre-learning activities focused on fall management. Based on this preparation, students analyzed the scenario and developed action plans for the simulation.

1) Developing a care plan for managing falls in older adults

Students anticipated their potential responses to encountering older adults who had fallen, creating detailed care plans for various scenarios. They also pledged to avoid repeating mistakes from previous clinical experiences.

Although the (fall management) algorithm was given by the professor..., I felt nervous, so the day before the simulation, I wrote down scenarios for all possible situations and prepared answers on how to deal with them, then I memorized them all (#10).

Last week, I cared for a maternal patient who kept complaining of pain during a virtual simulation... so I focused on learning more about pain assessment and nursing interventions to manage it (#14).

2) Using external observation to adjust the care plan before simulation-based practice

During the simulation-based practice, external observation provided valuable opportunities for students to adjust their care plans. Due to instructors simultaneously managing three groups (

Table 1), two groups could observe other groups’ simulation sessions before their own practice. This allowed them to learn from peers’ successes and mistakes, helping refine their own approaches to patient care. Through observation, students identified areas for improvement and gained deeper insights into essential nursing competencies, ultimately enhancing their readiness for simulation-based practice.

After observing other groups’ simulations, participants recognized successful actions and identified overlooked tasks, such as checking patients’ names and practicing proper hand hygiene. Watching peers communicate effectively with the patient, interact clearly with healthcare providers, and competently perform nursing activities provided valuable learning opportunities, allowing students to consider important aspects they had not previously contemplated.

Since my turn was late in the order, I observed what other students were doing and realized that I should react differently in certain situations… (#10).

When I heard words of empathy and support, such as, 'You must be having a hard time,' I reflected on becoming a nurse who prioritizes patient safety, even in emergencies (#49).

When the doctor said, “Is this Mrs. Yoon OO?” but said the wrong name, and the nurse said, “Yes, that’s right.” I realized the importance of accurately verifying the patient's name (#13).

2. Experiencing Patient Fall Management during Simulation-Based Practice

After completing pre-learning activities, students participated in simulation practice, during which they assessed and cared for an SP in her 70s who had fallen and was found lying on the floor.

1) Immersion in the clinical situation due to a human SP

The presence of an older adult as an SP enabled students to engage in realistic, two-way communication. This contributed to their sense of providing genuine patient care and facilitated full immersion in the scenario. Participants actively engaged in an urgent, realistic clinical situation, prompting them to think and act as nurses.

As I saw the patient in pain, I thought that I might not have helped the patient lay comfortably on the bed because of my weak arms, so I felt sorry, and I inadvertently said, “I’m sorry you’re in pain. I’m going to finish this quickly so bear with me a moment.” (#40).

2) Providing care for older adults with consideration of their difficulties

Participants empathized deeply with the SP as they observed first-hand the challenges older adults face, including declining physical abilities, hearing loss, pain from falling, and interactions with inexperienced healthcare providers. This empathy facilitated a better understanding of patients' difficulties and encouraged students to reflect on their own anxieties and perceptions.

I thought about how patients feel as they slowly develop diseases and see their bodies change. I was also surprised that this is the normal changes of aging. My view of older people changed, and I realized, ‘I could be in the same situation one day, and there would be nothing easy in their lives if young people don’t help.’ (#53).

3) Nervousness and lack of confidence regarding priorities and actions

Some students felt embarrassed due to their inability to respond calmly and proficiently during the simulation. Their minds often went blank when confronted with realistic clinical situations, leading to delayed responses and hesitancy in executing necessary tasks. They struggled to maintain composure under pressure, particularly in prioritizing tasks during the emergency scenario. Participants expressed frustration with their inability to provide optimal care, despite extensive preparation beforehand.

After one thing not working out as I’d expected, I just went blank and couldn’t decide what to do next. I broke out in cold sweat thinking that I couldn’t move on to the next step, since this problem was not solved (#49).

When the patient told me that she was sick, I doubted whether what I was doing right then was really a priority (#27).

Since the BP was normal earlier, I panicked when it increased to 155/93 mmHg. I wasn’t sure if I had measured it wrong or if I should measure it again” (#9).

3. Critical Reflection after Simulation-Based Practice

This phase occurred after completing simulation practice and involved the analysis of nursing performance. Reflective thinking and learning transitions were facilitated through instructor-led debriefings and guided reflective journal writing. While students expressed regret over certain ineffective nursing actions, they also experienced pride in their improvements. Through reflective journaling, students analyzed their educational experiences, enabling them to identify areas for further improvement and formulate plans for further improvement.

1) Identifying areas of improvement through critical reflection

This subcategory accounted for 35.5% of the meaningful statements within the reflective journals. Students analyzed their practice through guided reflective journaling, identifying strengths and weaknesses, and reflecting upon newly gained insights and areas requiring improvement to enhance their nursing competence. A frequent theme among students was their desire to develop nursing competencies to respond calmly and sensitively to changes in patients’ conditions.

I thought to myself that when evaluating geriatric patients, I would carefully consider their physical changes and accurately and quickly perform the next nursing activity without floundering, even if symptoms occur. Also, I want to be a nurse who empathizes with the feelings of older adults and attentively checks whether we are communicating well (#32).

Through this experience, I realized the importance of applying nursing care that considers the unique characteristics of each individual's life stage. I also recognized the need to prepare strategies for managing uncooperative patients (#19).

2) Feeling proud of progress as a nurse

The participants felt that they were slowly improving as nurses, and they gained a deeper understanding of fall care, empathy, and patient care through this education.

I felt confident and proud of what I do, and I think I could assess fall patients and report to doctors effectively after this simulation experience (#34).

3) Establishing perspectives on nursing role and responsibilities

This reflection underscored the essential qualities and responsibilities required of nurses in emergency situations, emphasizing the importance of responding swiftly and calmly to deliver effective patient care. Nurses recognized the need to address not only patients' physical health but also their psychological well-being, understanding that emotional support is as important as medical intervention. Participants acknowledged that, in high-pressure scenarios, maintaining composure and executing skillful actions instills trust and confidence in patients. Mental resilience and strict adherence to procedures, even under stress, were identified as critical components of effective nursing. Furthermore, sincere and genuine communication, as opposed to formal or mechanical interactions, was emphasized as crucial for building strong rapport and trust, reinforcing the pivotal role of nurses in these situations.

Nursing extends beyond treating physical difficulties; it involves empathizing with, comforting, and supporting patients who may be psychologically anxious or confused (#37).

I realized the importance of establishing a systematic approach among medical staff and maintaining a continuous attitude of inquiry and reflection to ensure accurate and prompt nursing actions based on well-developed protocols (#26).

Table 3 summarizes the quantitative analysis of the five reflection levels identified within the 53 reflective journals, totaling 185,021 words. Level 3 reflections accounted for 31.6% of the content, whereas level 5 reflections comprised 8.6% (

Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Reflective practice is recognized as a highly effective educational approach, and the use of guided reflection can further enhance its benefits [

16,

17]. In this study, guided reflective journaling required students to document their experiences, allowing them to critically reflect on the care processes, including patient interactions, assessments, and evaluations. This reflective approach helped students integrate their prior knowledge with practical simulation experiences, proving particularly effective in identifying areas needing improvement. Previous studies similarly report that guided reflective journaling enhances students’ clinical judgment, facilitates analysis of alternative nursing interventions, and aids students in prioritizing patient care plans [

5].

In this study, nursing students participated in simulation training using an SP. Simulation-based education involving SPs is known to improve clinical competency, communication skills, problem-solving abilities, and self-efficacy by enabling direct interactions and realistic, experiential learning [

9]. Using a 70-year-old SP provided students with tangible insights into geriatric care, allowing them to experience the physical characteristics of older adults, such as changes in skin texture, limited joint movement, and hearing difficulties (including the use of hearing aids), thereby deepening their understanding of aging-related challenges.

Two student groups participated in external observation. Previous studies indicate that external observation can help reduce students’ stress and anxiety and, for proactive learners, can offer valuable opportunities for peer discussion. However, without instructor guidance, students may struggle to evaluate whether their approaches are correct [

26]. A prior study reported that observing peers without instructor guidance or a structured checklist did not significantly enhance students’ performance [

26]. Although this study provided no such guidance during observations, we did not specifically evaluate the effects of this limitation; thus, its impact remains uncertain. Nevertheless, pre-learning the fall care protocol aided students in clearly understanding and applying nursing roles and problem-solving strategies during the simulation [

27], confirming that this study adhered to systematic simulation-based education guidelines.

The second category, “experiencing patient fall management through simulation-based practice,” illustrates how students became fully immersed in realistic, urgent clinical scenarios. Participants described experiencing nervousness and emotional distress upon discovering the SP on the floor, mirroring real clinical situations. Their varied emotional and cognitive responses were consistent with findings from previous simulation-based education studies [

22,

28]. This category also highlights students’ emotional responses and cognitive processes when they failed to effectively apply previously acquired theoretical knowledge in clinical practice.

The diverse responses to identical guided reflection questions indicate that students individually experienced distinct doubts, perspectives, and emotions concerning the same clinical scenario. This underscores the value of reflective journaling in facilitating personalized thinking processes, individualized reflection, motivated learning, and stimulating self-directed learning planning [

5]. Students reported recognizing their inadequacies as nurses after failing to fully implement care plans prepared prior to the simulation and experienced self-doubt regarding their clinical actions. Moreover, they gained experiential training in communication, patient education, empathy, and professional attitudes through direct interactions with the SP, elements that theoretical education alone cannot adequately provide. Observing peers’ attitudes and interactions enabled students to identify both appropriate and inappropriate nursing behaviors. These results align with previous findings indicating that post-simulation reflections and mutual observations stimulate critical thinking and enhance learners’ motivation [

28].

Utilizing an SP increases immersion by enabling realistic, two-way communication [

29]. In this study, employing an SP of similar age to the patient depicted in the scenario vividly illustrated realistic physical characteristics, such as skin texture and joint limitations, similar to those encountered in actual clinical practice. The SP’s use of a hearing aid was an unexpected but valuable enhancement to realism. However, a limitation of this study was not employing the SP as an evaluator. Future research could benefit from incorporating SPs as evaluators to offer additional insights and feedback.

The final category, “critical reflection after simulation-based practice,” demonstrated that participants gained significant insights into patients’ perspectives and effectively reflected on their future roles as nurses. Qualitative content analysis revealed that the most meaningful statements in this section (35.5%) emphasized guided reflective journaling’s role in enhancing critical reflection, confirming its effectiveness in identifying areas for improvement. Additionally, by reflecting on how they had thought and acted like nurses during the simulation, students experienced pride and confidence in their developing nursing competencies. These findings align with previous research indicating that learning transfer manifests as perceived satisfaction, confidence, and proficiency among learners [

10,

11]. The ongoing implementation of simulation-based education in a safe, structured environment, in conjunction with clinical practicums, could significantly contribute to deepening knowledge, promoting reflective practice, and strengthening nursing students’ professional confidence.

In this study, reflective journals were analyzed according to the five levels of reflection [

3,

11]. As shown in

Table 3, level 3 reflection (relating) accounted for the highest proportion at 31.6%, whereas level 5 reflection (reconstructing)—the highest level of critical thinking—comprised only 8.6%. These findings indicate that most students could effectively relate their experiences to theoretical knowledge, but fewer students reached the reconstructing level, which involves critical analysis and applying insights to future situations. The reflection levels observed in this study were higher compared to previous studies [

3,

13] and similar to those reported in medical education discussions [

30]. Although this study aimed to enhance nursing students’ reflective capabilities through semi-structured guided journaling and structured debriefing, the cross-sectional design limits causal interpretation. Therefore, replication studies and further research involving subjects with diverse professional experiences are recommended to establish stronger evidence. Nevertheless, the results suggest that guided reflective journaling can effectively assist students in achieving advanced reflection levels.

Guided reflective journal writing is recognized as a valuable educational tool that complements the limitations associated with oral debriefing, which typically occurs in a group setting with limited time, potentially restricting passive students’ opportunities to express themselves [

3,

5,

16,

17]. In this study, participants demonstrated their ability to reason and reconstruct situations based on their understanding and knowledge of fall prevention through guided reflective writing. Therefore, repeated journal writing exercises could promote critical reflection, representing the highest level of reflective thinking.

A limitation of this study is that only a single set of reflective journals was collected, preventing a longitudinal analysis of students’ developmental trajectories over time. Furthermore, the study focused solely on reflective journals without incorporating in-depth interviews or quantitative measures of students’ learning experiences, resulting in incomplete understanding. Future mixed-methods studies, integrating both qualitative and quantitative data, would be valuable to provide a more comprehensive examination of students’ learning experiences. Additionally, because data extraction and analysis occurred after data collection was complete, real-time assessment of data saturation during collection was not feasible. Confirming saturation only during the analysis phase constitutes an additional study limitation.

Despite these limitations, this study offers several important implications. Guided reflective journaling effectively stimulated critical thinking and deeper reflection by allowing students to thoughtfully examine their behaviors and emotions during the learning process [

16]. Additionally, analyzing these reflective journals provided valuable insights into the depth of students’ reflective thinking after simulation practice. Moreover, students’ first-hand descriptions of their experiences and thought processes during simulation-based education offer valuable feedback for instructors, contributing to the design and continuous improvement of future simulation-based curricula.

CONCLUSION

The ultimate objective of nursing education is to facilitate students’ ability to effectively transfer knowledge acquired through lectures and clinical practicums into actual patient care. This study provided partial evidence of the learning-transfer process among nursing students, demonstrating how the use of an age-matched SP in simulation education, combined with guided reflective journal writing, enabled students to progress beyond theoretical nursing knowledge and apply that knowledge effectively in clinical scenarios. Furthermore, developing and implementing an ongoing simulation-based education curriculum would enrich our understanding of the complete learning-transfer process and the long-term educational impact. Therefore, simulation-based education and reflective practice should not be conducted as isolated or single events, but rather integrated within regular nursing education curricula.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Youn-Jung Son, a contributing editor of the Korean Journal of Adult Nursing, was not involved in the editorial evaluation or the decision to publish this article. The other authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Conceptualization and supervision - GYK; data curation, investigation, and project administration - GYK and GEC; formal analysis, methodology, software, and writing - original draft - GYK and JWA; validation and writing - review and editing - GYK, YJS, and JWA.

-

FUNDING

None.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

None.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data can be obtained from the corresponding authors.

Table 1.Outline of Simulation-based Education for the Initial Management of Falls in Older Adults

|

Sessions |

Contents |

Methods |

|

(1) Orientation (30 minutes) |

Overview of simulation of practice: |

Lecture using written materials |

|

- Purpose of simulation |

|

- Scenario outline |

|

- Introduction to pre-learning topics: initial and re-evaluation of fall patients, interpreting evaluation results, therapeutic communication |

|

(2) Pre-learning (3 hours 30 minutes) |

Fall preventions |

Pre-study (1 hour 30 minutes) |

|

Management of fall patients |

- Instructor provides a learning list and guidance |

|

Group discussion (2–3 students per group) (1 hour) |

|

- Analyze fall risk factors and demonstrate prevention strategies using illustrations |

|

- Instructor: questions and answers during discussion |

|

Presentation and feedback (1 hour) |

|

(3) Simulation practice (2 hours) |

Initial management of falls in older adults: using a standardized patient |

Group 1: Pre-briefing/simulation/preparation for debriefing/observation of another team/debriefing (1 hour) |

|

- Standardized patient: 70-year-old female |

Group 2: Pre-briefing/observation of another team/simulation/preparation for debriefing/debriefing (1 hour) |

|

- Groups of 2–3 students |

Group 3: Pre-briefing/preparation for simulation/observation of another team/simulation and preparation for debriefing/debriefing (1 hour) |

|

Instructor: Pre-briefing/simulation and observation of other team/debriefing |

|

(4) Review and journal writing (2 hours) |

Review of fall prevention and management in older adults |

Review with instructor (30 minutes) |

|

Guided reflective journal writing |

Individual student’s journal writing (1 hour 30 minutes) |

Table 2.Content Analysis of Students’ Reflective Journals on Simulation-Based Fall Management Education (N=53)

|

Categories |

Subcategories |

Meaningful statements |

n (%) |

|

Preparing for simulation-based practice |

Developing a care plan for managing falls in older adults |

Before simulation, I created scenarios for all possible situations and memorized responses. |

36 (5.8) |

|

I developed a care plan by reviewing fall management algorithms and practicing assessment sequences. |

|

Using external observation to adjust the care plan before simulation-based practice |

Watching peers perform patient care allowed me to adjust my care plan for better preparedness. |

77 (12.5) |

|

Experiencing patient fall management during simulation-based practice |

Immersion in the clinical situation due to a human standardized patient |

Hearing the patient’s moans made the situation feel intensely real. |

45 (7.3) |

|

Interacting with a live patient increased my sense of responsibility. |

|

Providing care for older adults with consideration of their difficulties |

I adjusted my speech to be louder and slower for the older adult patient. |

54 (8.8) |

|

Nervousness and lack of confidence in priorities and actions |

I froze and forgot my planned steps upon seeing the fallen patient. |

62 (10.0) |

|

Hearing the patient’s moans made me panic and doubt my actions. |

|

Critical reflection after simulation-based practice |

Identifying areas of improvement through critical reflection |

Taking notes is essential for structured communication and accurate information delivery. |

219 (35.5) |

|

Fall assessment requires evaluating both pain and potential neurological damage. |

|

Feeling proud of progress as a nurse |

I felt proud of maintaining composure and following the fall protocol smoothly. |

67 (10.9) |

|

Successfully explaining procedures to the patient increased my confidence as a nurse. |

|

Establishing perspectives on nursing role and responsibilities |

Providing both physical and emotional care is essential for effective patient-centered nursing. |

57 (9.2) |

|

Total |

|

|

617 (100.0) |

Table 3.Levels of Reflections in Students’ Reflective Journals on Simulation-Based Fall Management Education (185,021 words)

|

Levels of reflection |

5Rs |

n (%) |

|

Level 1 describes a situation, incident, or issue. |

Reporting |

26,261 (14.2) |

|

Level 2 records the emotional or personal response to the experience. |

Responding |

27,156 (14.7) |

|

Level 3 reports on understanding of the situation/issue and how it relates to theory exposes taking personal and theoretical experience as reference. |

Relating |

58,452 (31.6) |

|

Level 4 interrogates, explores, or explains. |

Reasoning |

40,887 (22.1) |

|

Level 5 draws a conclusion and develops a future course of action based on reasoning. |

Reconstructing |

15,925 (8.6) |

|

Not coded |

|

16,340 (8.8) |

REFERENCES

- 1. Korea Patient Safety Reporting & Learning System. 2023 Korean patient safety incident report [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Institute for Healthcare Accreditation; 2024 [cited 2024 October 30]. Available from: https://www.koiha-kops.org/

- 2. Cho I, Park KH, Suh M, Kim EM. Evidence-based clinical nursing practice guideline for management of inpatient falls: adopting the guideline adaptation process. J Korean Acad Fundam Nurs. 2020;27(1):40-51. https://doi.org/10.7739/jkafn.2020.27.1.40

- 3. Tiago Horta RD. Falls prevention in older people and the role of nursing. Br J Community Nurs. 2024;29(7):335-9. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjcn.2024.0005

- 4. Roca J, Reguant M, Tort G, Canet O. Developing reflective competence between simulation and clinical practice through a learning transference model: a qualitative study. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;92:104520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104520

- 5. Dewart G, Corcoran L, Thirsk L, Petrovic K. Nursing education in a pandemic: academic challenges in response to COVID-19. Nurse Educ Today. 2020;92:104471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104471

- 6. Smith T. Guided reflective writing as a teaching strategy to develop nursing student clinical judgment. Nurs Forum. 2021;56(2):241-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12528

- 7. Alharbi A, Nurfianti A, Mullen RF, McClure JD, Miller WH. The effectiveness of simulation-based learning (SBL) on students’ knowledge and skills in nursing programs: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2024;24(1):1099. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-06080-z

- 8. Ma J, Lee Y, Kang J. Standardized patient simulation for more effective undergraduate nursing education: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Simul Nurs. 2023;74:19-37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2022.10.002

- 9. Kim YJ, Jung KH. Nursing students’ experiences in simulation education with standardized patients. J Korean Soc Simul Nurs. 2022;10(2):19-34. https://doi.org/10.17333/JKSSN.2022.10.2.19

- 10. Hustad J, Johannesen B, Fossum M, Hovland OJ. Nursing students’ transfer of learning outcomes from simulation-based training to clinical practice: a focus-group study. BMC Nurs. 2019;18:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-019-0376-5

- 11. El Hussein MT, Cuncannon A. Nursing students’ transfer of learning from simulated clinical experiences into clinical practice: a scoping review. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;116:105449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2022.105449

- 12. Bain JD, Ballantyne R, Mills C, Lester NC. Reflecting on practice: student teachers’ perspectives. Flaxton: Post Pressed; 2002.

- 13. Lim JY, Ong SY, Ng CY, Chan KL, Wu S, So WZ, et al. A systematic scoping review of reflective writing in medical education. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03924-4

- 14. Fegran L, Ten Ham-Baloyi W, Fossum M, Hovland OJ, Naidoo JR, van Rooyen DR, et al. Simulation debriefing as part of simulation for clinical teaching and learning in nursing education: a scoping review. Nurs Open. 2023;10(3):1217-33. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1426

- 15. Fanning RM, Gaba DM. The role of debriefing in simulation-based learning. Simul Healthc. 2007;2(2):115-25. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0b013e3180315539

- 16. Dulloo P, Vedi N, Patel M, Singh S. Empowering medical education: unveiling the impact of reflective writing and tailored assessment on deep learning. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2024;12(3):163-71. https://doi.org/10.30476/JAMP.2024.101594.1938

- 17. Parrish DR, Crookes K. Designing and implementing reflective practice programs: key principles and considerations. Nurse Educ Pract. 2014;14(3):265-70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2013.08.002

- 18. Carpenter CR, Cameron A, Ganz DA, Liu S. Older adult falls in emergency medicine: 2019 update. Clin Geriatr Med. 2019;35(2):205-19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2019.01.009

- 19. Korean Hospital Nurses Association. Evidence-based clinical nursing practice guideline: preventing falls in hospitlas [Internet]. Seoul: Korean Hospital Nurses Association; 2018 [cited 2024 October 30]. Available from: https://khna.or.kr/home/data/nak_01.pdf

- 20. Korea Patient Safety Reporting and Learning System. Patient safety and warning: falls in the older adults in health care facilities [Internet]. Seoul: Korea Institute for Healthcare Accreditation; 2024 [cited 2024 October 30]. Available from: https://www.kops.or.kr/portal/board/news/boardDetail.do?bbsId=news&nttNo=20000000001894

- 21. Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing Education. Simulation practice standards 2017 [Internet]. Seoul: Korean Accreditation Board of Nursing Education; 2017 [cited 2024 October 30]. Available from: http://www.kabone.or.kr/reference/refRoom.do

- 22. Park J, Hong J. Content analysis of the reflective journaling after simulation based practice education of nursing students. J Korea Soc Simul Nurs. 2019;7(1):13-29. https://doi.org/10.17333/JKSSN.2019.7.1.13

- 23. Krippendorff K. Content analysis: an introduction to its methodology. 4th ed. London: Sage Publications; 2019.

- 24. Sandelowski M. The problem of rigor in qualitative research. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1986;8(3):27-37. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-198604000-00005

- 25. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349-57. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- 26. Delisle M, Ward MA, Pradarelli JC, Panda N, Howard JD, Hannenberg AA. Comparing the learning effectiveness of healthcare simulation in the observer versus active role: systematic review and meta-analysis. Simul Healthc. 2019;14(5):318-32. https://doi.org/10.1097/SIH.0000000000000377

- 27. Jeffries PR. Simulation in nursing education: from conceptualization to evaluation. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2020.

- 28. Anine M, Kari R, Monica O, Hilde SS. Health professional students’ self-reported emotions during simulation-based education: an interpretive descriptive study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;63:103353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2022.103353

- 29. Ross JG, Furman G, Scheve A. The impact of standardized patients on first-year nursing students’ communication skills. Clin Simul Nurs. 2024;89:101513. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecns.2024.101513

- 30. Kim YJ, Lee SH, Yoo HH. Analysis of students’ reflective journals on medical communication role plays. Korean Med Educ Rev. 2017;19(3):169-74. https://doi.org/10.17496/kmer.2017.19.3.169

Appendices

Appendix 1.

- Utilization of Standardized Patient