Abstract

-

Purpose

This study aimed to assess the level of depression among older adults experiencing tinnitus and to identify predictive factors of depression through an analysis of secondary data.

-

Methods

Data from the ninth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey conducted in 2022 were utilized for this analysis. We examined individuals aged 60 years or older who had experienced tinnitus for more than 6 months. Complex sample analysis techniques were conducted, and multiple regression analysis was performed to identify predictors of depression.

-

Results

The study included 231 participants. Significant differences in depression levels were observed across several demographics and health factors, including gender, education level, self-rated health status, living alone, and stress level. Depression levels were significantly correlated with self-rated health status, stress levels, and average sleep duration. Additionally, significant correlations were found between self-rated health and stress levels, self-rated health and the number of chronic diseases, as well as between stress levels and the number of chronic diseases. Multiple regression analysis indicated that self-rated health status (p<.001), stress level (p<.001), and average sleep duration (p=.042) were significantly associated with depression. Specifically, poorer self-rated health, higher stress levels, and shorter sleep duration were associated with higher levels of depression.

-

Conclusion

In older patients with tinnitus, self-rated health status, stress level, and average sleep duration significantly impact depression levels. These findings provide an important foundation for developing interventions to reduce depression in individuals with tinnitus.

-

Key Words: Depression; Health status; Sleep duration; Stress; Tinnitus

INTRODUCTION

Tinnitus is defined as a psychological response to auditory perceptions that occur in the absence of external stimuli. Unlike auditory hallucinations associated with psychosis, tinnitus is characterized by its lack of clarity and specific meaning [

1]. The characteristics and impact of tinnitus vary widely, and its prevalence increases with age. Therefore, the number of individuals affected by tinnitus is likely to rise as the population of older adults grows. According to a systematic review of 113 studies published between 1972 and 2021, approximately 14.4% of the global adult population suffers from tinnitus, with prevalence rising to 23.6% among those aged 65 and older [

2]. In Europe, tinnitus affects 14.7% of individuals at some point in their lives, with incidence rates increasing significantly with age and auditory decline [

3]. In Korea, about 20.7% of the population report tinnitus, and 29.3% describe severe symptoms that disrupt daily activities [

4]. In women with normal hearing, the prevalence of tinnitus is higher and is associated with conditions such as ischemic heart disease, dyslipidemia, noise exposure, and notably, depression-the most significant contributing factor to tinnitus [

5]. Moreover, depression and insufficient sleep duration are interrelated and significantly correlated with tinnitus symptoms [

6]. Thus, accurately assessing the severity of depression in older individuals with tinnitus and identifying mediating factors is essential. A thorough understanding of these factors is fundamental for increasing the effectiveness of early nursing interventions.

Tinnitus poses both physical and psychological challenges and has a chronic impact on quality of life-a burden expected to intensify as human lifespans increase [

7]. Prior studies have identified key variables associated with depression in older adults; for example, older individuals who rate their health negatively tend to exhibit higher levels of depression [

8]. Additionally, older adults experiencing high levels of daily stress are at increased risk of developing depression [

9]. Although short-term acute stress can be adaptive and motivating, chronic stress may induce significant alterations in the central nervous system, contributing to the development of conditions such as depression, hypertension, and coronary heart disease [

10]. Sleep deprivation and changes in sleep patterns are also associated with depressive symptoms in older adults [

9]. Insomnia-which can exacerbate depression and further reduce quality of life-affects between 28.1% and 76.0% of individuals with tinnitus [

11]. The negative effects of tinnitus often intensify in quiet environments, particularly at bedtime [

12]. Such sleep disturbances can worsen the discomfort caused by tinnitus and lead to daytime fatigue and drowsiness [

12]. Insufficient sleep has been shown to aggravate symptoms of depression and anxiety, including increased irritability, impaired concentration, lack of motivation, and diminished memory [

13]. A recent study on adults over 50 found that poor sleep quality is associated with heightened depression [

14]. Persistent tinnitus can contribute to depression, anxiety, poor sleep quality, and reduced concentration [

15]. When acute tinnitus becomes chronic, 70.0~80.0% of patients adapt within approximately six months; however, the remaining 20.0~30.0% experience significant disruptions in sleep and cognitive activities, which may further exacerbate depression [

16]. Furthermore, smoking and excessive alcohol consumption are linked to higher levels of depression in older adults, and the risk increases with the number of chronic diseases [

9]. Additionally, older individuals living alone are reported to have a higher risk of developing depression compared to those living with others [

8]. In contrast, some studies have shown that regular physical activity is effective in alleviating depressive symptoms in older adults [

17].

A 2006 study that combined data from 28 studies involving 9,979 tinnitus patients across 15 countries found that the prevalence of depression among adult tinnitus patients was 33.0% [

18]. Similarly, data from 28,930 adults in the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) from 2008 to 2012 indicated that both the presence and severity of tinnitus are significantly associated with depression and suicidal ideation, highlighting clear interactions [

19]. Consequently, early intervention is crucial to mitigate tinnitus and its related complications. It is strongly recommended that depression predictors be accurately selected and analyzed in a randomly chosen general population while excluding bias and heterogeneity. The aim of this study is to assess the level of depression among older individuals who have experienced tinnitus and to identify predictive factors for depression using descriptive research methods. The findings of this study can offer practical support to older community members with tinnitus and enhance the intervention process by improving understanding of psychological disorders and complications, thereby serving as a foundation for rehabilitation interventions.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This cross-sectional study involved a secondary data analysis of the ninth KNHANES, which was conducted in 2022.

2. Setting and Samples

A total of 231 individuals aged 60 years or older who reported experiencing tinnitus for more than six months were selected as research subjects. In KNHANES, tinnitus was assessed via a self-reported questionnaire in which participants indicated whether their symptoms persisted for more than 5 minutes.

KNHANES is a statutory survey conducted under Article 16 of the National Health Promotion Act and is designated as an official government statistic (approval number 117002) under Article 17 of the Statistics Act. The survey is approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee of the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and its results are publicly disclosed through press releases, statistical publications, and raw data disclosure by December of the following year.

Because KNHANES is a sample survey rather than a complete census, the complex sample design must be considered when extrapolating results to the entire population of the Republic of Korea. In the first year of the ninth cycle (2022), a total of 9,437 individuals were surveyed, with 6,265 participating in at least one component of the health questionnaires, medical examinations, or nutrition surveys, resulting in a participation rate of 66.4%. The cumulative participation rates in previous cycles were 78.3% for the sixth cycle (2013~2015), 76.6% for the seventh cycle (2016~2018), and 74.0% for the eighth cycle (2019~2021).

In the ninth KNHANES (2022), samples were selected based on regional and household characteristics using a stratified sampling method. This method ensured representation across administrative divisions and housing types while also considering household size and demographic distribution. Among the 6,265 participants in 2022, 340 individuals reported tinnitus lasting more than six months. Of these, 261 individuals aged 60 or older were selected, and after excluding 30 individuals with missing data, 231 subjects were finally analyzed.

This study was conducted following an exemption from review approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the researchers' affiliated institution (IRB No. E2410/002-006. The researcher registered according to usage guidelines and received anonymized raw data based on information officially released on the KNHANES website (

https://knhanes.cdc.go.kr/).

1) Sociodemographic characteristics

These variables were analyzed based on age, income quintile, education level, type of public health insurance, and private health insurance enrollment.

2) Disease and health behavior related characteristics

Self-rated health status was evaluated by asking, "How do you generally perceive your health?" Respondents chose from the following options: "very good," "good," "average," "poor," or "very poor." Stress level was assessed by asking, "How much stress do you typically experience in your daily life?" with responses including: "very high," "high," "low," or "almost none."

Sleep duration was measured by recording the average number of hours slept per day during weekdays and weekends as separate variables. Alcohol consumption was evaluated by asking about the frequency of drinking over the past year, with response options including: "not at all in the past year," "less than once a month," "about once a month," "2~4 times a month," "2~3 times a week," or "4 or more times a week."

The number of chronic diseases was determined by assessing the presence of specific diagnoses, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, asthma, atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, sinusitis, otitis media, kidney disease, and obstructive sleep apnea. The total number of diagnosed chronic conditions was then counted and analyzed.

Aerobic exercise adherence was classified into two categories. Individuals were considered not to meet the recommended level of aerobic exercise if they did not engage in at least 2 hours and 30 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity, 1 hour and 15 minutes of vigorous-intensity physical activity, or an equivalent combination of both (with 1 minute of vigorous-intensity activity considered equivalent to 2 minutes of moderate-intensity activity) per week. Conversely, individuals meeting these criteria were classified as adhering to the recommended level of aerobic exercise. For the analysis, the numerator included participants who met the recommended level of aerobic physical activity, and the denominator included all participants aged 19 years or older.

3) Social support

Social support variables included whether participants lived alone or with others and whether they lived with a spouse.

4) Depression

In the 2022 KNHANES, depression level was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a validated screening tool for evaluating the severity of depressive symptoms and monitoring treatment response. Developed by Spitzer et al., the PHQ-9 is structured according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) criteria for major depressive disorder. It consists of nine items that measure the frequency of depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. Each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale: 0 (not at all), 1 (several days), 2 (more than half the days), and 3 (nearly every day), resulting in a total score ranging from 0 to 27. A total score of 10 or higher indicates clinically significant depression. The internal consistency reliability of the PHQ-9, calculated using Cronbach's ⍺, was high at .84, with item removal tests yielding values between 0.76 and 0.81, indicating little change in reliability.

4. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 29.0, Armonk, NY). To accurately estimate the characteristics of the target population (i.e., individuals residing in South Korea), final weights provided by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) were applied. These weights were generated through post-stratification adjustments that included design weights, non-response adjustment weights, post-calibration weights, and handling of extreme weights. The final weights accounted for the complex survey design and improved the representativeness of the results. Statistical analyses were conducted by incorporating the complex sample design, considering the weight variable (wt-itvex), stratification variable (kstrata), and cluster variable (psu). First, descriptive statistics and frequency analyses were performed to characterize the sociodemographic, disease and health behavior characteristics, social support, and depression levels among older individuals with and without tinnitus. Subsequently, the impacts of sociodemographic factors, disease and health behavior characteristics, and social support on depression levels in older individuals experiencing tinnitus were analyzed using complex sample linear regression.

RESULTS

1. Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

The study analyzed 231 individuals aged 60 years or older who had experienced tinnitus for at least six months. The sociodemographic characteristics of these participants are presented in

Table 1. The average age was 69.73±0.48 years. Men constituted 50.5% of the sample. Regarding education, 40% had less than an elementary school degree, while 15.8% held a graduate degree or higher. In terms of household income, 32.6% were in the middle-lower income quintile. When asked about alcohol consumption over the past year, 48.3% reported complete abstinence, and 88.1% indicated that they did not smoke. With regard to living arrangements, 83.9% lived with family compared to 16.1% who lived alone, and 79.4% reported living without a spouse. More than 80% of the participants were enrolled in private health insurance in addition to the universal coverage provided by national health insurance. Among the participants, 50% rated their health as fair, and the majority reported experiencing moderate stress. The average sleep duration was 6.53± 0.11 hours, and the average number of chronic diseases was 1.66±0.11. Regarding aerobic physical activity, 67.6% did not meet the recommended guidelines.

Significant differences in depression levels were observed based on gender (

p=.004), education (

p=.035), self-rated health (

p<.001), living arrangements (living alone versus with others;

p=.003), marital status (having a spouse,

p=.026), perceived stress (

p<.001), and aerobic exercise adherence (

p=.020) (

Table 2).

Specifically, women reported significantly higher depression scores than men (p=.004). Participants with an elementary school education or lower exhibited higher depression scores compared to those with higher educational attainment (p=.035). Individuals who rated their health as "very poor" or "poor" had higher depression scores than those reporting better health conditions (p<.001). Elderly individuals living alone had significantly higher depression scores than those living with others (p=.003), and participants without a spouse had higher depression scores compared to married individuals (p=.026). Furthermore, higher perceived stress levels were strongly associated with increased depression, with those reporting "very high" stress exhibiting the highest scores (p<.001). Additionally, participants who did not engage in aerobic physical activity had significantly higher depression scores than those who did (p=.020).

3. Correlations among the Main Variables

Correlation analysis indicated significant relationships between depression level and self-rated health (r=-.42,

p<.001), the level of stress (r=.36,

p<.001), and average sleep duration (r=-.18,

p=.010) (

Table 3). This suggests that lower self-rated health, shorter sleep duration, and higher stress levels are associated with increased depression. Significant correlations were also found between self-rated health and the level of stress, self-rated health and the number of chronic diseases, the level of stress and the number of chronic diseases.

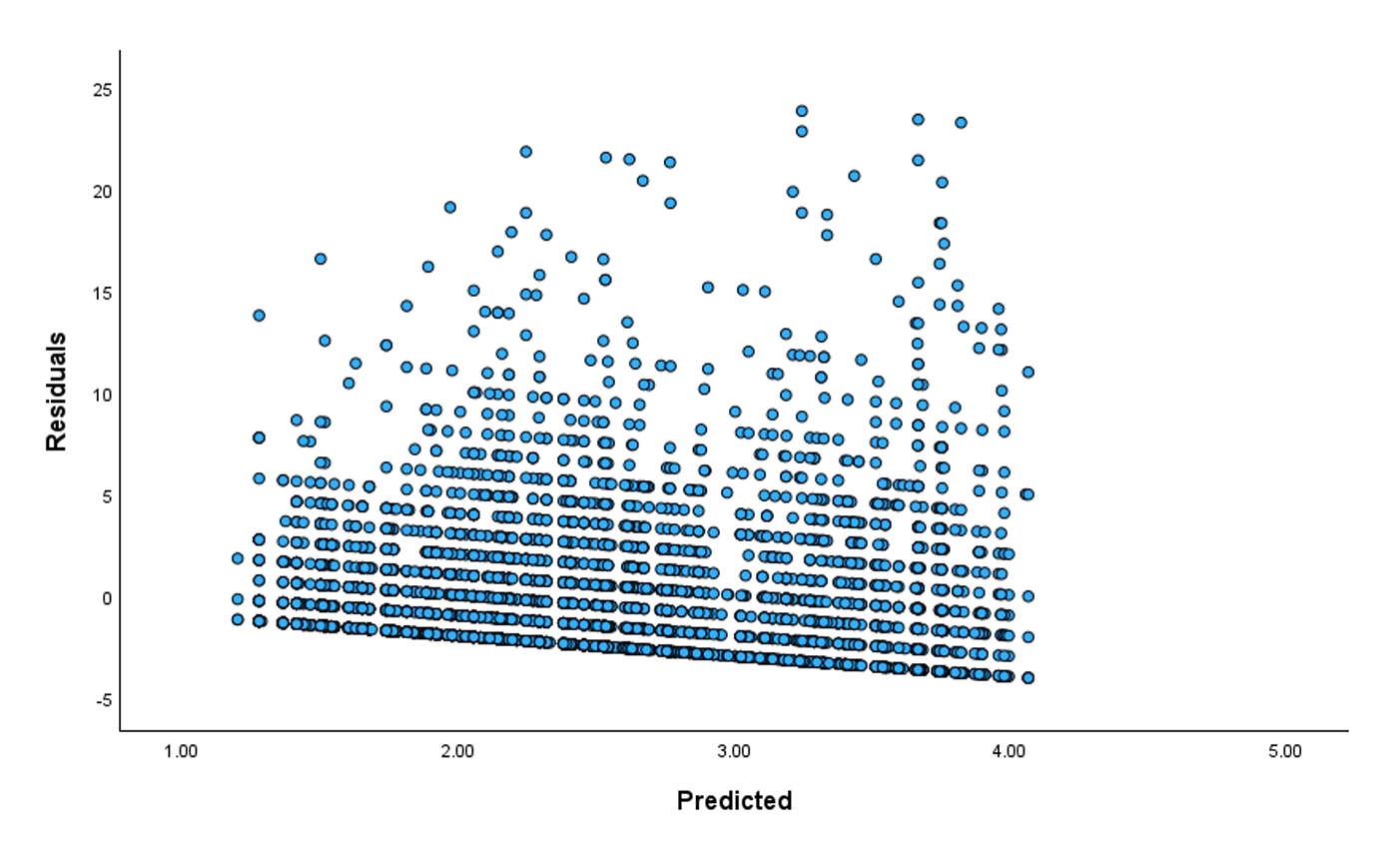

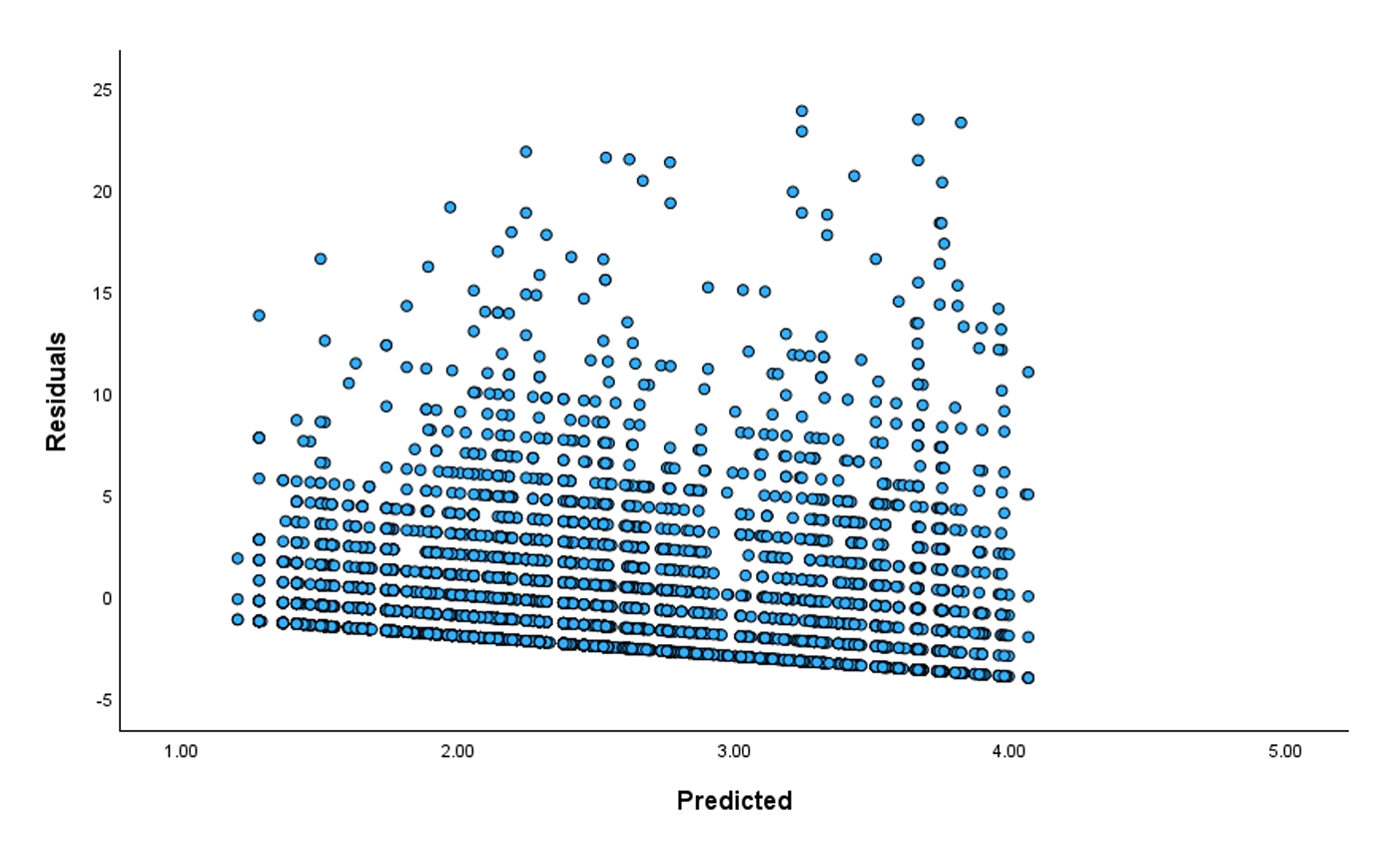

Multiple logistic regression models were employed to identify predictive factors for depression. Multicollinearity is generally considered present when the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) exceeds 10. In this study, VIF values ranged from 1.1 to 2.68, confirming the absence of multicollinearity among the independent variables. A weighted residual analysis, reflecting the complex sample design, was conducted, and the results are presented in

Figure 1. Multiple regression analysis revealed that self-rated health (

p<.001), stress level (

p<.001), and average sleep duration (

p=.042) significantly influenced depression (

Table 4). Specifically, poorer self-rated health (B=-1.13, t=-5.80,

p<.001), higher stress levels (B=1.21, t=3.93,

p<.001), and shorter sleep durations (B=-0.26, t=-2.05,

p=.042) were associated with higher depression scores. The complex sample multiple regression analysis yielded an R2 value of 0.31 and an F-statistic of 7.37.

DISCUSSION

This study found that among the seven disease and health behavior characteristics examined, three-self-rated health status, perceived stress, and average daily sleep duration-had a significant impact on depression in older individuals with tinnitus. Although not statistically significant, the number of chronic diseases was higher among older individuals with tinnitus, and adherence to aerobic exercise was greater among those without tinnitus. These findings align with previous research. The aging population faces an increasing health concern as tinnitus, characterized by the perception of ringing, buzzing, hissing, whistling, or other sounds without external stimuli, becomes more prevalent among older adults. Recent studies suggest that approximately one in ten adults in the United States have experienced tinnitus within the past year [

20]. Notably, the prevalence of tinnitus increases with age; an estimated 8.7% of adults aged 45 and older report some form of tinnitus, with 7.4% experiencing chronic tinnitus [

21]. In the present study, the prevalence of chronic tinnitus was observed in 5.4% of participants (based on 2022 data). Tinnitus can substantially impact older adults, as it is linked to functional impairments in thought processing, emotions, hearing, sleep, and concentration, thereby negatively affecting quality of life [

21].

Patients with tinnitus often report a greater degree of discomfort than would be expected from their general health status. As the duration of tinnitus increases, psychological pressures intensify, exacerbating the physical anomalies associated with the condition. Stress, defined as an emotional response to perceived inadequacies in coping ability [

10], can lead to new mental health issues, including depression and other disorders, thereby significantly reducing quality of life. Tinnitus perception is maintained by non-auditory neural circuits, and stress responses activate and inhibit several neuroendocrine axes-primarily the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary axis-that regulate various metabolic and immune functions [

22]. These responses include increased blood pressure, heart rate, glucose metabolism, glucose production, lipolysis, proteolysis, and insulin resistance, while gastrointestinal activity and the need for appetite and sleep are reduced. Observational research among German participants has indicated that 60% of individuals with tinnitus suffer from long-term emotional distress, and about 25.0% attribute chronic stress as a major cause of tinnitus. The experience of tinnitus-related pain is mediated by individual emotional states [

10]. Although the correlation between tinnitus-related pain and sympathetic nerve activity is positive-and, conversely, there is a negative correlation with parasympathetic nerve activity-interventions that enhance parasympathetic activity-such as ensuring adequate sleep and promoting psychological stability-are considered effective [

10]. Despite variations in the intensity of the reported positive correlations between stress and tinnitus levels depending on the measurement instrument used, as well as inconsistent changes post-intervention, this study supports the use of psychological cognitive behavioral therapy. This therapeutic method, which reduces perceived pain and restores homeostasis by increasing subjective well-being, is recommended as an effective intervention [

10].

Additionally, our study demonstrates that average daily sleep duration significantly influences depression levels among older individuals, with those without tinnitus reporting longer sleep durations. Although this finding is consistent with trends from previous research, direct comparisons must be approached with caution due to methodological differences. For example, a study conducted at a tertiary hospital in southwest China assessed tinnitus severity and sleep quality using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) and the Mandarin version of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI-M). In that study, 181 patients with tinnitus of at least six months duration were examined, and significant differences were found between Group A (PSQI<7) and Group B (PSQI≥7) in both THI-M scores (

p<.001) and tinnitus severity (

p=.006), with poorer sleep quality linked to more severe tinnitus. Furthermore, THI-M and PSQI scores showed a positive correlation in Group B (

p<.001), suggesting that past sleep quality may influence tinnitus severity [

11,

23].

Furthermore, prior research has frequently linked severe tinnitus with poor sleep quality. For example, a retrospective analysis conducted between 2010 and 2020 of 2,344 tinnitus patients in a German tertiary hospital found that 40.9% of patients were dissatisfied with their sleep quality, suggesting a potential relationship between insomnia, sleep disorders, and tinnitus severity. Although the directionality of this relationship remains unclear, evidence points to a bidirectional interaction between sleep disturbances and tinnitus symptoms [

24]. Recent reports further indicate that while tinnitus patients experience subjective difficulties with sleep initiation, these issues are not always reflected in objective sleep metrics [

25]. This discrepancy may result from variations in measurement standards and interpretation methods.

However, it is crucial to acknowledge the limitations of directly comparing these studies, as their findings are context-specific and influenced by differences in patient populations, measurement tools, and study designs. Direct comparisons with the present study may result in overgeneralizations or inaccuracies. Nevertheless, the current study's focus on average daily sleep duration offers valuable insights into the general relationship between sleep and depression in older individuals, underscoring the need for further research to clarify the complex, bidirectional interactions among tinnitus, sleep, and psychological well-being.

It is worth noting that the regression model in this study had an R-squared value of 0.31, indicating that the model explains only a modest proportion of the variance in depression. This limitation is likely due to the use of secondary data and the inherent variability introduced by the complex survey analysis. Secondary data may not include variables that are specifically tailored to the study's objectives, potentially limiting the model's explanatory power. Furthermore, the application of complex survey methods-such as weighting, stratification, and clustering-can introduce additional variability, thereby reducing the model's overall explanatory power.

A domestic study further supports the findings of this research. In that study, 393 tinnitus patients assessed between 2018 and 2021 were evaluated for their general condition, disease characteristics, tinnitus disability index (TDI), PSQI, and self-assessment anxiety scale (SAS). The results indicated a strong association between sleep disorders and anxiety, particularly among females, those with hearing loss, or those with severe tinnitus. Moreover, sleep disturbances were identified as a key factor contributing to anxiety. Recent KNHANES data, involving 9,693 individuals aged 20 years and older, revealed that 29.0% were diagnosed with sleep disorders and 9.0% reported severe tinnitus. Negative sleep characteristics were significantly linked to severe tinnitus, although no notable correlation was found between sleep disorders and hearing loss [

26]. These findings suggest that the relationship between sleep deprivation and tinnitus likely operates independently of the auditory system. From this perspective, cognitive behavioral therapy and counseling are recommended to minimize the impact of sleep disturbances on depression in tinnitus patients. These therapies can enhance parasympathetic nerve activity, which contributes to emotional stability. Additionally, reducing environmental noise may facilitate sleep initiation and maintenance for patients with tinnitus. Stress management programs that incorporate relaxation techniques, such as deep breathing and meditation, may also serve as valuable nursing interventions. These approaches not only help reduce stress but also promote parasympathetic activity, potentially alleviating tinnitus symptoms. Furthermore, educational programs for patients and caregivers can improve understanding of tinnitus, its triggers, and management strategies, thereby empowering individuals to actively manage their symptoms and reduce associated anxiety.

Finally, the study found that depression scores were approximately 25.0% higher in older individuals with tinnitus compared to those without the condition. This finding is consistent with recent studies. For example, KNHANES data indicated that tinnitus may significantly deteriorate mental health and health-related quality of life (HRQoL), particularly among older adults [

27]. In Germany, both male and female patients with chronic tinnitus reported lower mental HRQoL relative to their physical HRQoL, with female patients experiencing more pronounced mental and physical HRQoL impairments [

28]. Supporting these findings, a study of 5,418 participants in Rotterdam (average age 69.0 years) conducted between September 2019 and April 2020 found that individuals with disruptive tinnitus reported lower sleep quality, higher depression levels, and more mental health issues than those without tinnitus [

29]. Research utilizing British Biobank resources, involving 171,728 participants, indicated that severe tinnitus patients were at increased risk for depression (odds ratio, 1.27), although it remains unclear whether tinnitus predisposes individuals to depression [

30]. Similarly, KNHANES data found that adults with tinnitus are more likely to develop depression, though the causal link remains uncertain [

30]. The Gutenberg Health Study, which surveyed 8,539 individuals using the PHQ-9, GAD -7, and SSS-8 questionnaires, revealed that 28.0% (n=2,387) suffered from tinnitus, and those affected were more prone to depression or somatic symptom disorders [

31]. A review of the current findings alongside previous studies consistently confirms that patients with high tinnitus scores exhibit markedly lower HRQoL and higher depression scores, independent of auditory characteristics [

32]. Tinnitus is increasingly recognized as a non-auditory cognitive disorder in which subjective and psychological factors play a significant role. In particular, alterations in perceived sleep duration and quality are critical in the development of depression and have a profound impact on quality of life. Thus, creating an adequate sleep environment is essential for promoting emotional stability and facilitating both mental and physical recovery through psychological interventions.

Tinnitus, a common auditory condition characterized by the perception of sound without an external stimulus, can significantly impair the quality of life for older individuals. Given the complex and multifaceted nature of tinnitus, a comprehensive approach to clinical management is essential, particularly for older adults who may face additional challenges due to comorbidities and age-related physiological changes. One promising therapeutic approach for older individuals with tinnitus is antioxidant therapy. Recent studies suggest that antioxidants may help manage tinnitus by addressing underlying mechanisms such as oxidative stress and inflammation [

33]. In fact, a study examining the effects of antioxidant therapy in older tinnitus patients found that antioxidant use led to significant improvements in tinnitus-related symptoms and quality of life [

33]. In addition to pharmacological interventions, cognitive-behavioral therapy has shown promising results in managing tinnitus among older adults. A randomized controlled trial demonstrated that cognitive-behavioral therapy reduced tinnitus-related distress and improved overall well-being in older patients [

34]. Another important consideration is the potential role of the frontostriatal network in tinnitus. Recent research has highlighted the significance of this brain network in the pathophysiology of tinnitus and its potential as a therapeutic target [

35]. Furthermore, collaboration among medical professionals-including physicians, audiologists, and psychologists-is crucial for developing a comprehensive and effective treatment plan for older individuals with tinnitus.

This study has several limitations. First, it did not fully control for the influence of various demographic variables, suggesting that the findings should be interpreted cautiously. Second, although the study used a panel survey that facilitates establishing causality and observing changes over time, it relied on only one year of data. Future research should analyze multi-year data to more definitively ascertain causal relationships.

CONCLUSION

For individuals aged 60 or older who have experienced tinnitus, self-rated health status, stress level, and average sleep duration significantly influence depression levels. Psychological or cognitive-behavioral therapy is recommended to enhance emotional stability. Additionally, creating a conducive sleep environment through measures such as environmental noise reduction is advised as an effective intervention.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and /or design acquisition - KS and TSH; Analysis - KS; Interpretation of the data - KS; Drafting or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content - KS and TSH.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The first author received a scholarship from the BK21 education program (Center for Human-Caring Nurse Leaders for the Future).

Figure 1.Weighted residual analysis.

Table 1.Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample (N=231)

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

n (%) or M±SE |

|

Gender |

Men |

122 (50.5) |

|

Women |

109 (49.5) |

|

Age |

|

69.73±0.48 |

|

Educational level |

Elementary school or lower |

106 (40.0) |

|

Middle school |

42 (18.2) |

|

High school |

49 (26.0) |

|

Graduate school or higher |

34 (15.8) |

|

Income quintile (household) |

Lower |

60 (23.1) |

|

Middle lower |

82 (32.6) |

|

Middle |

39 (21.1) |

|

Upper middle |

36 (16.3) |

|

Upper |

14 (6.9) |

|

Frequency of drinking in the past year |

Never |

111 (48.3) |

|

Less than once a month |

40 (17.3) |

|

1 time per month |

19 (7.8) |

|

2~4 times per month |

20 (9.3) |

|

2~3 times per week |

21 (8.6) |

|

4 or more times per week |

20 (8.7) |

|

Living with others |

Yes |

191 (83.9) |

|

No |

40 (16.1) |

|

Living with spouse |

Yes |

44 (20.6) |

|

No |

187 (79.4) |

|

Public health insurance type |

National health insurance |

223 (96.1) |

|

Medical aid |

8 (3.9) |

|

Current smoking status |

No |

204 (88.1) |

|

Yes |

27 (11.9) |

|

Private health insurance coverage |

Yes |

80 (30.9) |

|

No |

151 (69.1) |

|

Self-rated health |

Very poor |

10 (2.9) |

|

Poor |

29 (10.7) |

|

Average |

108 (50.0) |

|

Good |

61 (27.0) |

|

Very good |

23 (9.4) |

|

2.70±0.07 |

|

Stress level |

Almost none |

54 (21.4) |

|

Low |

145 (63.7) |

|

High |

25 (12.8) |

|

Very high |

7 (2.1) |

|

3.04±0.04 |

|

Average sleep duration (hour) |

|

6.53±0.11 |

|

The number of chronic diseases |

|

1.66±0.11 |

|

Aerobic exercise adherence |

No |

163 (67.6) |

|

Yes |

68 (32.4) |

Table 2.Differences in Depression Level according to General Characteristics of the Participants (N=231)

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

M±SE |

t or F |

p

|

|

Gender |

Men |

1.61±0.23 |

-2.91 |

.004 |

|

Women |

2.65±0.26 |

|

|

|

Age |

|

|

|

.234 |

|

Education |

Elementary school or lower |

2.84±0.34 |

2.92 |

.035 |

|

Middle school |

1.61±0.38 |

|

|

|

High school |

1.76±0.36 |

|

|

|

Graduate school or higher |

1.47±0.37 |

|

|

|

Income quintile (household) |

Lower |

2.69±0.45 |

1.00 |

.411 |

|

Middle lower |

2.12±0.28 |

|

|

|

Middle |

1.60±0.31 |

|

|

|

Upper middle |

2.18±0.55 |

|

|

|

Upper |

1.71±0.71 |

|

|

|

Frequency of drinking in the past year |

Never |

2.32±0.28 |

1.39 |

.231 |

|

Less than once a month |

2.21±0.44 |

|

|

|

1 time per month |

1.72±0.54 |

|

|

|

2~4 times per month |

1.64±0.48 |

|

|

|

2~3 times per week |

1.17±0.46 |

|

|

|

4 or more times per week |

2.67±0.90 |

|

|

|

Self-rated health |

Very poor |

4.70±1.10 |

14.14 |

<.001 |

|

poor |

3.39±0.39 |

|

|

|

Average |

1.35±0.18 |

|

|

|

Good |

0.62±0.20 |

|

|

|

Very good |

0.65±0.33 |

|

|

|

Living with others |

Yes |

1.87±0.19 |

-2.98 |

.003 |

|

No |

3.45±0.49 |

|

|

|

Living with spouse |

Yes |

1.85±0.20 |

2.23 |

.026 |

|

No |

3.15±0.52 |

|

|

|

Public health insurance type |

National health insurance |

2.09±0.18 |

0.52 |

.606 |

|

Medical aid |

2.88±1.05 |

|

|

|

Stress level |

Almost none |

1.07±0.28 |

8.38 |

<.001 |

|

Low |

1.98±0.20 |

|

|

|

High |

3.80±0.77 |

|

|

|

Very high |

6.77±1.41 |

|

|

|

Current smoking status |

No |

2.16±0.19 |

0.43 |

.667 |

|

Yes |

1.86±0.65 |

|

|

|

Average sleep duration |

|

|

|

.010 |

|

The number of chronic diseases |

|

|

|

.225 |

|

Aerobic exercise adherence |

No |

2.40±0.22 |

2.35 |

.020 |

|

Yes |

1.54±0.29 |

|

|

|

Private health insurance coverage |

Yes |

2.07±0.34 |

0.19 |

.851 |

|

No |

2.15±0.22 |

|

|

Table 3.Correlations among the Main Variables (N=231)

|

Variables |

Self-rated health |

Stress level |

Sleep duration |

Number of chronic diseases |

Depression level |

|

r (p) |

r (p) |

r (p) |

r (p) |

r (p) |

|

Self-rated health |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

Stress level |

.18 (.021) |

1 |

|

|

|

|

Sleep duration |

.00 (.801) |

.06 (.840) |

1 |

|

|

|

Number of chronic diseases |

.14 (.035) |

.18 (.015) |

.06 (.371) |

1 |

|

|

Depression level |

-.42 (<.001) |

.36 (<.001) |

-.18 (.010) |

.08 (.225) |

1 |

Table 4.Predictive Factors of Depression (N=231)

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

B |

SE |

t |

p

|

|

(Constant) |

|

11.82 |

1.86 |

6.37 |

<.001 |

|

Gender |

Men |

-0.32 |

0.38 |

-0.84 |

.401 |

|

Women (ref.) |

|

|

|

|

|

Education |

Elementary school or lower |

0.14 |

0.51 |

0.28 |

.784 |

|

Middle school |

-0.25 |

0.50 |

-0.50 |

.616 |

|

High school |

-0.35 |

0.47 |

-0.75 |

.453 |

|

Graduate school or higher (ref.) |

|

|

|

|

|

Income quintile (household) |

Lower |

0.07 |

0.75 |

0.10 |

.925 |

|

Middle lower |

0.11 |

0.71 |

0.15 |

.879 |

|

Middle |

-0.60 |

0.76 |

-0.80 |

.425 |

|

Upper middle |

0.04 |

0.84 |

0.05 |

.959 |

|

Upper (ref.) |

|

|

|

|

|

Self-rated health |

|

-1.13 |

0.20 |

-5.80 |

<.001 |

|

Living with others |

Yes (ref.) |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

-1.08 |

0.95 |

-1.14 |

.255 |

|

Living with spouse |

Yes (ref.) |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

-0.51 |

0.99 |

-0.52 |

.603 |

|

Stress level |

|

1.21 |

0.31 |

3.93 |

<.001 |

|

Average sleep duration |

|

-0.26 |

0.13 |

-2.05 |

.042 |

|

Aerobic exercise adherence |

Yes (ref.) |

|

|

|

|

|

No |

0.06 |

0.43 |

0.15 |

.881 |

|

Model summary |

|

R2=.31, F=7.37, p<.001 |

REFERENCES

- 1. Baguley D, McFerran D, Hall D. Tinnitus. The Lancet. 2013;382(9904):1600-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60142-7

- 2. Jarach CM, Lugo A, Scala M, van den Brandt PA, Cederroth CR, Odone A, et al. Global prevalence and incidence of tinnitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurology. 2022;79(9):888-900. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2022.2189

- 3. Mazurek B, Boecking B, Dobel C, Rose M, Bruggemann P. Tinnitus and influencing comorbidities. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie. 2023;102(Suppl 1):S50-8. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1950-6149

- 4. Kim HJ, Lee HJ, An SY, Sim S, Park B, Kim SW, et al. Analysis of the prevalence and associated risk factors of tinnitus in adults. Public Library of Science One. 2015;10(5):e0127578. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127578

- 5. Choi J, Lee CH, Kim SY. Association of tinnitus with depression in a normal hearing population. Medicina. 2021;57(2):114. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina57020114

- 6. Bhatt JM, Bhattacharyya N, Lin HW. Relationships between tinnitus and the prevalence of anxiety and depression. The Laryngoscope. 2017;127(2):466-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/lary.26107

- 7. Joung WJ. A grounded theory study on the symptom acceptance of tinnitus patients. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing. 2018;30(6):611-21. https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2018.30.6.611

- 8. Kim MC. Predictors of depression of elderly living alone: focusing on decision tree analysis. Crisisonomy. 2024;20(11):73-90.

- 9. Kim B. Factors influencing depressive symptoms in the elderly: using the 7th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES VII-1). Journal of Health Informatics and Statistics. 2020;45(2):165-72. https://doi.org/10.21032/jhis.2020.45.2.165

- 10. Mazurek B, Boecking B, Bruggemann P. Association between stress and tinnitus-new aspects. Otology & Neurotology. 2019;40(4):e467-73. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAO.0000000000002180

- 11. Lu T, Li S, Ma Y, Lai D, Zhong J, Li G, et al. Positive correlation between tinnitus severity and poor sleep quality prior to tinnitus onset: a retrospective study. Psychiatry Quarterly. 2020;91(2):379-88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-019-09708-2

- 12. Li YL, Hsu YC, Lin CY, Wu JL. Sleep disturbance and psychological distress in adult patients with tinnitus. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2022;121(5):995-1002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfma.2021.07.022

- 13. Ogawa S, Kitagawa Y, Fukushima M, Yonehara H, Nishida A, Togo F, et al. Interactive effect of sleep duration and physical activity on anxiety/depression in adolescents. Psychiatry Research. 2019;273:456-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.085

- 14. Maddox PA, Elahi A, Khuram H, Issani A, Hirani R. Sleep quality and physical activity in the management of depression and anxiety. Preventive Medicine. 2023;171:107514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107514

- 15. Choi SW, Lee HM, Kim D, Jeong HJ. The effect of antidepressant in the treatment of tinnitus. Journal of Clinical Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery. 2018;29(1):36-41. https://doi.org/10.35420/jcohns.2018.29.1.36

- 16. Husain FT. Perception of, and reaction to, tinnitus: the depression factor. Otolaryngologic Clinics of North America. 2020;53(3):555-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otc.2020.03.005

- 17. Lee H, Kim A, Choi S. A systematic review of the effects of physical activity on depression in community-dwelling older adults: using the Neuman System Model. Health and Social Welfare Review. 2022;42(1):356-73. https://doi.org/10.15709/hswr.2022.42.1.356

- 18. Salazar JW, Meisel K, Smith ER, Quiggle A, McCoy DB, Amans MR. Depression in patients with tinnitus: a systematic review. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2019;161(1):28-35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599819835178

- 19. Han KM, Ko YH, Shin C, Lee JH, Choi J, Kwon DY, et al. Tinnitus, depression, and suicidal ideation in adults: a nationally representative general population sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2018;98:124-32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.01.003

- 20. Bhatt J, Lin HW, Bhattacharyya N. Prevalence, severity, exposures, and treatment patterns of tinnitus in the United States. JAMA Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2016;142(10):959-65. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2016.1700

- 21. Gallus S, Lugo A, Garavello W, Bosetti C, Santoro E, Colombo P, et al. Prevalence and determinants of tinnitus in the Italian adult population. Audiology & Neurotology. 2015;45(1):12-9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000431376

- 22. Elarbed A, Fackrell K, Baguley DM, Hoare DJ. Tinnitus and stress in adults: a scoping review. International Journal of Audiology. 2021;60(3):171-82. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992027.2020.1827306

- 23. Asnis GM, Henderson M, Thomas M, Kiran M, De La G R. Insomnia in tinnitus patients: a prospective study finding a significant relationship. The International Tinnitus Journal. 2020;24(2):65-9.

- 24. Weber FC, Schlee W, Langguth B, Schecklmann M, Schoisswohl S, Wetter TC, et al. Low sleep satisfaction is related to high disease burden in tinnitus. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(17):11005. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191711005

- 25. de Feijter M, Oosterloo BC, Goedegebure A, Luik AI. The cross-sectional association between tinnitus and actigraphy-estimated sleep in a population-based cohort of middle-aged and elderly persons. Ear and Hearing. 2023;44(4):732-9. https://doi.org/10.1097/AUD.0000000000001320

- 26. Awad M, Abdalla I, Jara SM, Huang TC, Adams ME, Choi JS. Association of sleep characteristics with tinnitus and hearing loss. Otolaryngology Open. 2024;8(1):e117. https://doi.org/10.1002/oto2.117

- 27. Park HM, Jung J, Kim JK, Lee YJ. Tinnitus and its association with mental health and health-related quality of life in an older population: a nationwide cross-sectional study. Journal of Applied Gerontology. 2022;41(1):181-6. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820966512

- 28. Boecking B, Biehl R, Brueggemann P, Mazurek B. Health-related quality of life, depressive symptoms, anxiety, and somatization symptoms in male and female patients with chronic tinnitus. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2021;10(13):2798. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10132798

- 29. Oosterloo BC, de Feijter M, Croll PH, Baatenburg de Jong RJ, Luik AI, Goedegebure A. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between tinnitus and mental health in a population-based sample of middle-aged and elderly persons. JAMA Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2021;147(8):708-16. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2021.1049

- 30. McCormack A, Edmondson-Jones M, Fortnum H, Dawes PD, Middleton H, Munro KJ, et al. Investigating the association between tinnitus severity and symptoms of depression and anxiety, while controlling for neuroticism, in a large middle-aged UK population. International Journal of Audiology. 2015;54(9):599-604. https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2015.1014577

- 31. Hackenberg B, Doge J, O'Brien K, Bohnert A, Lackner KJ, Beutel ME, et al. Tinnitus and its relation to depression, anxiety, and stress: a population-based cohort study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023;12(3):1169. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm12031169

- 32. Weidt S, Delsignore A, Meyer M, Rufer M, Peter N, Drabe N, et al. Which tinnitus-related characteristics affect current health-related quality of life and depression? a cross-sectional cohort study. Psychiatry Research. 2016;237:114-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.065

- 33. Polanski JF, Soares AD, Cruz OL de M. Antioxidant therapy in the elderly with tinnitus. Brazilian Journal of Otorhinolaryngology. 2015;82(3):269-74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2015.04.016

- 34. Andersson G, Porsaeus D, Wiklund M, Kaldo V, Larsen HC. Treatment of tinnitus in the elderly: a controlled trial of cognitive behavior therapy. International Journal of Audiology. 2005;44(11):671-5. https://doi.org/10.1080/14992020500266720

- 35. Zhou GP, Chen YC, Li WW, Wei HL, Yu YS, Zhou QQ, et al. Aberrant functional and effective connectivity of the front striatal network in unilateral acute tinnitus patients with hearing loss. Brain Imaging and Behavior. 2022;16(1):151-60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-021-00486-9