Abstract

-

Purpose

This study aimed to investigate the frequency and perceived importance of 52 clinical research nursing activities in Korea and to apply importance–performance analysis (IPA) to identify areas requiring improvement.

-

Methods

A descriptive survey was conducted among 96 clinical research nurses (CRNs) with ≥2 years of experience. Data were collected online in May 2022 using a questionnaire addressing 14 general characteristics and 52 clinical research nursing activities across five dimensions: clinical practice (CP), study management (SM), care coordination and continuity, human subjects protection, and contributing to the science (CS), as defined by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH). Frequency and importance were evaluated on a 6-point Likert scale. Analyses included descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation coefficients, the t-test, analysis of variance with Duncan post hoc tests, and IPA.

-

Results

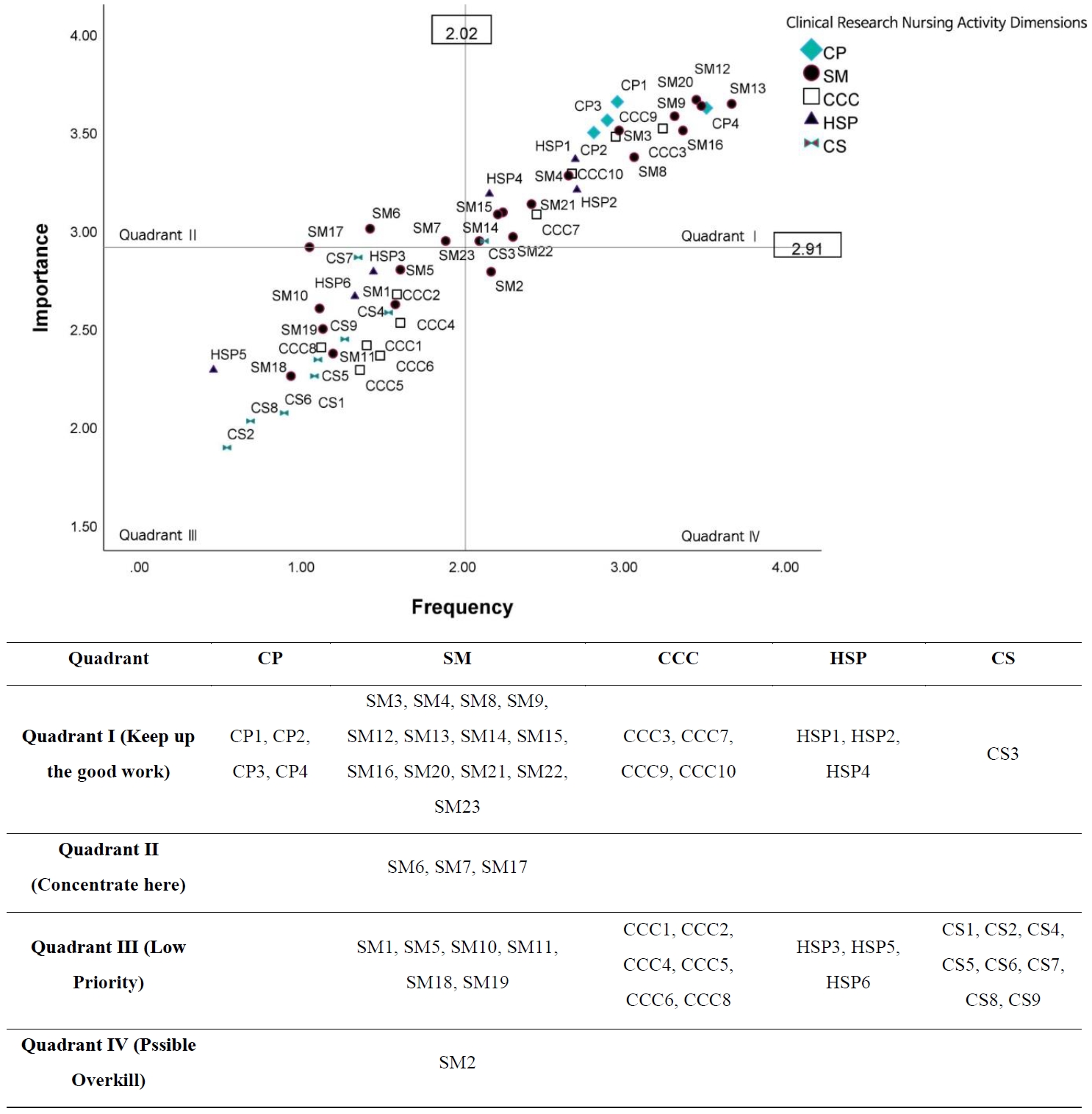

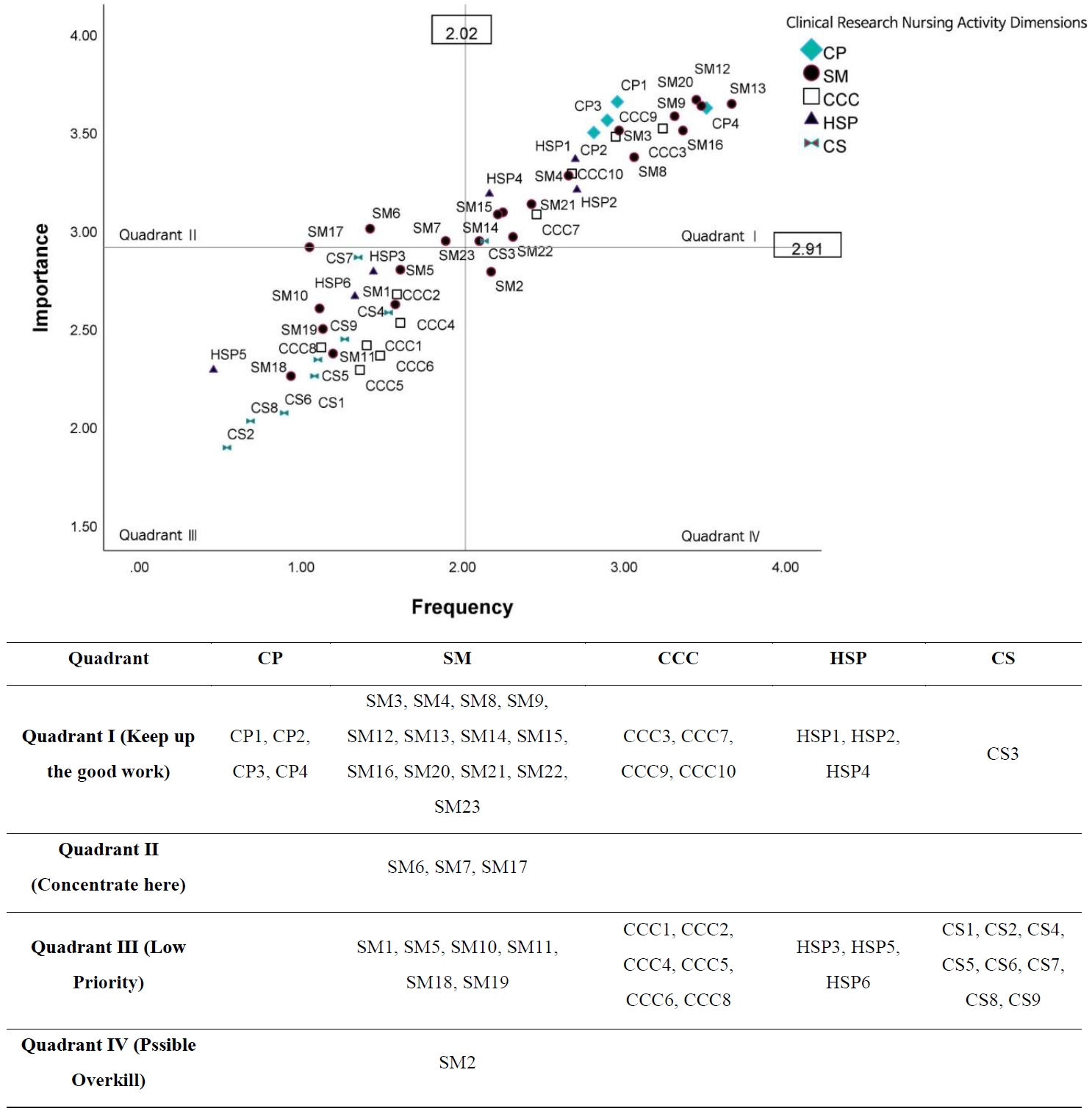

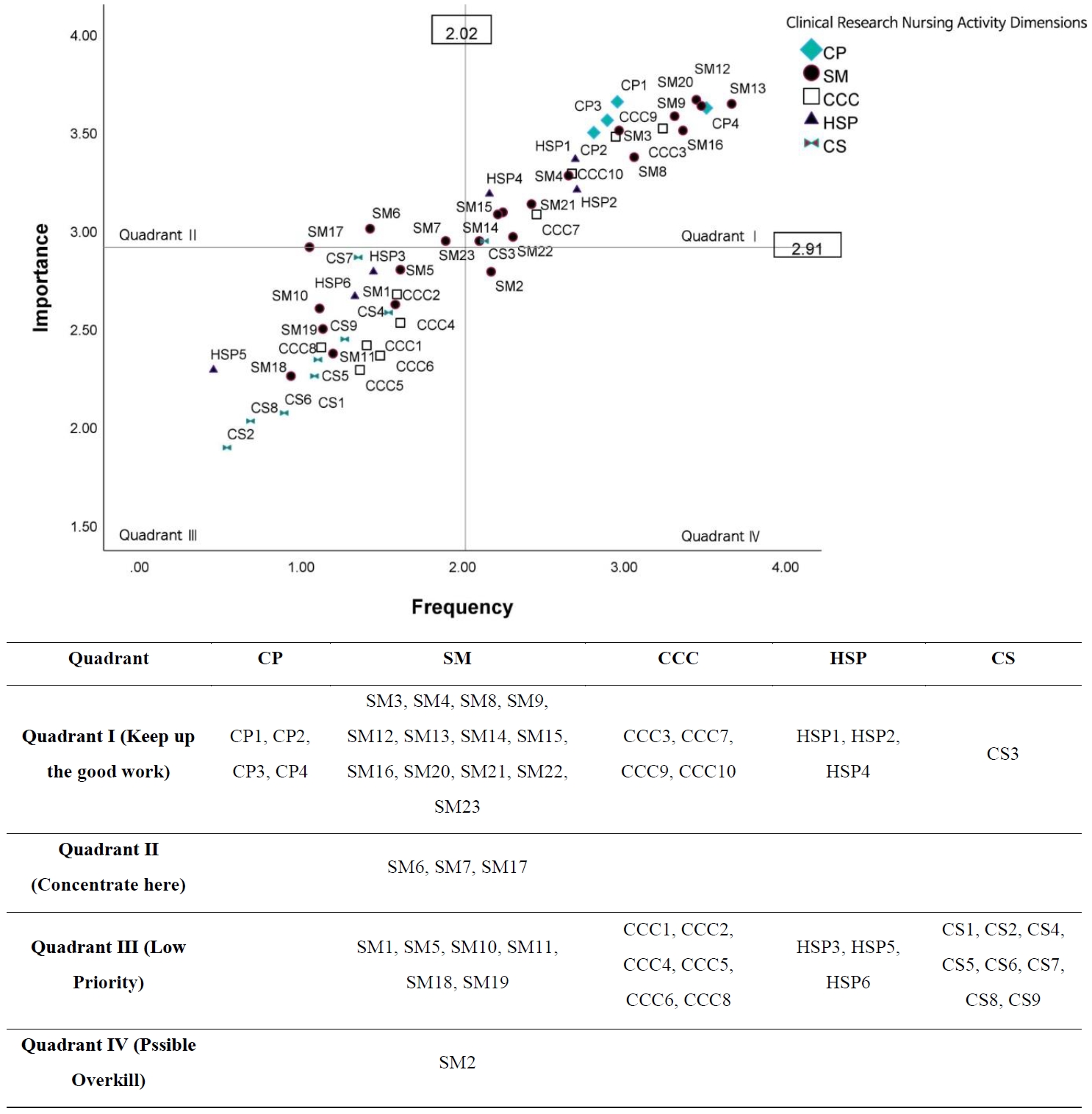

The mean frequency and importance scores for the 52 activities were 2.02±1.27 and 2.91±1.24, respectively. CP activities were performed most often and rated as most important, whereas CS activities were performed least often and rated as least important. Higher education, certification, and professional association membership were associated with higher CS activity frequencies. IPA revealed strengths in CP and core SM activities, while regulatory reporting, data integrity assurance, and site audits were underperformed despite being highly important.

-

Conclusion

Korean CRNs play essential roles in CP and SM but require enhanced education, institutional support, and clearer role delineation in regulatory and quality-assurance activities. These findings provide evidence to guide CRN education, policy development, and the strengthening of professional identity among CRNs in Korea.

-

Key Words: Clinical study; Nurses; Nursing

INTRODUCTION

Clinical research refers to studies in which investigators directly engage with living human subjects, human-derived specimens, behaviors, or phenomena. Among these, clinical trials assess the safety and efficacy of investigational medicinal products, medical devices, and advanced regenerative biotechnologies and monitor adverse events [

1,

2]. In Korea, clinical research has expanded markedly in recent years. As of 2023, Korea ranked fourth globally in clinical trial market share, and Seoul has held the top global position for the number of clinical trial activities for seven consecutive years since 2017. Various professionals contribute to clinical research, with clinical research coordinators (CRCs) representing 21.5% of the workforce [

3]. In Korea, most CRCs (89.7%–89.8%) are nurses, and the term “clinical research nurse” (CRN) is frequently used interchangeably with CRC [

4,

5]. The textbook Basic Education for Clinical Trial Personnel, published by the Ministry of Food and Drug Safety in 2005, also referred to CRCs as CRNs [

6].

International discussions regarding CRN roles date back to the 1910s, and by the 1960s, the need for specialized knowledge and skills had become evident [

7]. With the expansion of clinical trials, the number of CRNs grew throughout the 1980s and 1990s, accompanied by a growing body of literature describing their roles. In 2009, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical Center in the United States formally defined CRN roles and identified 52 core professional nursing activities organized into five dimensions: clinical practice (CP), study management (SM), care coordination and continuity (CCC), human subjects protection (HSP), and contributing to the science (CS) [

8].

Bevans et al. [

9] conducted a role delineation study using these 52 activities and reported that CP had the highest frequency and importance, whereas CS had the lowest. The single most frequently performed activity was “Provide direct care to research participant” within CP, while the least frequently performed was “Serve as an Institutional Review Board (IRB) member” within HSP. However, that study did not prioritize improvement needs because it did not assess discrepancies between frequency and importance.

Since then, the American Nurses Association officially recognized clinical research nursing as a nursing specialty in 2016 and published Clinical Research Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice in 2017. In 2021, the International Association of Clinical Research Nurses developed a core curriculum to advance CRN professional development, further systematizing CRN identity and standards of practice [

10,

11].

In Korea, the demand for CRNs has increased alongside the rapid growth of clinical research. However, clear definitions and empirical studies of clinical research nursing practice remain limited. Do [

12] cataloged 121 research nurse tasks based on four roles—educator, advocate, direct care provider, and clinical trial operator—outlined by the Korea Food and Drug Administration. Hwang [

13] developed a job description for oncology clinical trial nurses. Yet, these studies, conducted more than 15 years ago, do not adequately reflect the rapidly evolving clinical research environment.

Therefore, research is needed to examine CRN activities in Korea using the 52 core activities across five dimensions identified by the NIH Clinical Center [

8] and Bevans et al. [

9]; to compare Korean CRN activities with international benchmarks; and to apply importance–performance analysis (IPA) to identify key areas for improvement. Such research could clarify CRN roles, provide evidence for education and policy development, and strengthen professional nursing practice in the Korean context. Accordingly, this study assessed the frequency and perceived importance of the 52 clinical research nursing activities across five dimensions among Korean CRNs and applied IPA to evaluate current practices, identify critical improvement needs, and propose strategic directions to enhance CRN professionalism.

The specific objectives of this study were as follows: (1) to identify the general characteristics of participants, (2) to investigate the frequency, importance, and correlations of the 52 clinical research nursing activities across five dimensions, (3) to compare differences in activity frequency across dimensions according to participants’ characteristics, and (4) to visualize the distribution of the frequency and importance of the 52 activities using scatterplots and to conduct IPA to identify key activities requiring improvement.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This study employed a descriptive survey design to examine the frequency, perceived importance, and correlations of clinical research nursing activities performed by CRNs in Korea, using the list of 52 clinical research nursing activities defined by the NIH Clinical Center. The study is reported in accordance with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines.

2. Setting and Samples

The participants were CRNs working in Korea. To ensure sufficient clinical research experience, inclusion criteria required nurses to have participated in clinical research for at least two years within the past five years. Exclusion criteria were as follows: individuals who participated in clinical research without any direct face-to-face interaction with research participants throughout the study period (for example, those involved only in data entry, data management, or medical record review), and those who conducted only in vitro diagnostic medical device studies using residual specimens.

The required sample size for correlation analysis was calculated using G*Power 3.1.9.7. Assuming a correlation coefficient of 0.3, a significance level of .05, a statistical power of .8, and a two-tailed test, the minimum required sample size was 84 participants [

14]. In this study, 96 participants were ultimately included.

1) General characteristics of the participants

Fourteen items were used to assess participants’ demographic and work-related characteristics. These included age, sex, educational level, marital status, region, annual salary, place of work, employment type, clinical research experience within the past five years, number of ongoing projects, types of clinical research participated in, possession of clinical trial professional certification, affiliation with a relevant professional association, and the presence of job guidelines. Initially, possession of clinical trial professional certification was surveyed as two separate credentials, but these were combined into a single variable for analysis to reflect their stepwise structure.

2) Frequency and importance of clinical research nursing activities

The frequency and perceived importance of clinical research nursing activities were measured using the list of 52 activities across five dimensions developed by the NIH Clinical Center Nursing Team [

8]. This tool is publicly available for download and use by CRNs. As no prior studies had used an officially translated Korean version, the 52 activities were translated into Korean by the researcher, reviewed by five practicing CRNs for accuracy and clarity, and further refined through consultation with a bilingual Korean-American nursing faculty member and a Korean nursing faculty member. The five dimensions are (1) CP, (2) SM, (3) CCC, (4) HSP, and (5) CS. (1) The CP dimension (4 items) involves providing direct care and support to research participants and their families. (2) The SM dimension (23 items) includes ensuring participant safety, addressing clinical needs, and supporting protocol integrity and data collection. (3) The CCC dimension (10 items) focuses on integrating research and clinical activities and coordinating study requirements. (4) The HSP dimension (6 items) emphasizes advocacy for participant safety and rights. (5) The CS dimension consists of nine items representing activities that contribute to science in general, particularly to nursing science and practice, including developing new ideas, exploring innovations, and applying research findings to practice [

15].

In this study, the frequency score indicated how often a CRN performs each activity, whereas the importance score reflected the perceived significance of each activity in the CRN’s role [

9]. Each item was rated on a 6-point Likert scale. For frequency 0, not part of my practice; 1, infrequently/1 to 2 times per year; 2, monthly; 3, weekly; 4, once per day; 5, multiple times per day. For importance 0, not part of my role; 1, not important to my role; 2, somewhat important to my role; 3, important to my role; 4, very important to my role; 5, essential to my role. A higher frequency score indicated more frequent performance of the activity, and a higher importance score indicated greater perceived importance in the clinical research environment. Bevans et al. [

9] reported Cronbach’s α=.95 for frequency and α=.96 for importance. In the present study, Cronbach’s α was .94 for frequency and .98 for importance.

Data were collected from May 13 to May 17, 2022. To recruit participants, an IRB-approved recruitment notice was posted on three online platforms where CRCs with nursing licenses actively participate. The notice included the study topic, purpose, inclusion and exclusion criteria, participation procedures, estimated time required, potential benefits, principal investigator’s information, survey link, and contact details. Eligible individuals who consented to participate accessed the survey link independently, completed the online questionnaire, and submitted their responses. The questionnaire required approximately 15 minutes to complete. In this online survey, completion of all items was mandatory for submission; therefore, no missing data were present.

5. Ethical Considerations

This study was conducted after obtaining approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kangwon National University Hospital (IRB No. 2022-03-002). Upon accessing the survey link, participants received the IRB contact information to ensure their rights and protection. Information regarding data security and disposal was provided, and informed consent for the collection of personal information was obtained. Upon completing the questionnaire, all participants received a mobile beverage coupon as compensation.

6. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics ver. 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The general characteristics of participants were analyzed using descriptive statistics, including frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations. The reliability of the measurement tool was assessed using Cronbach’s α.

The mean and standard deviation of frequency and importance of the 52 clinical research nursing activities across the five dimensions were calculated using descriptive statistics. Correlations between frequency and importance were examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. Data normality was verified by confirming sample size adequacy based on the Central Limit Theorem and by evaluating skewness and kurtosis according to the criteria proposed by Kline [

16]. Differences in activity frequency across dimensions based on participants’ characteristics were analyzed using the independent t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan’s post hoc test.

The distribution of frequency and importance of the 52 activities was visualized using scatterplots. Frequency scores were plotted on the x-axis as a proxy indicator of performance, and importance scores were plotted on the y-axis. Mean values of frequency and importance were used as reference lines to divide the scatterplots into four quadrants. Based on this framework, IPA was conducted to identify key activities requiring improvement. IPA is an analytical technique that visualizes a two-dimensional graph using importance and performance as its axes and is applied to determine priorities effectively [

17].

RESULTS

1. General Characteristics of Participants

The general characteristics of the participants are presented in

Table 1. The mean age was 32.81±6.91 years, and the majority were female (n=91, 94.8%). Most participants held a bachelor’s degree (76.0%), and more than half reported an annual salary of less than 40 million KRW (n=49, 51.0%). The largest proportion were employed at university hospitals (72.9%), and 31 participants (32.3%) were permanent employees. Only 24 participants (25.0%) held a clinical trial professional certification, and 23 (24.0%) reported affiliation with a relevant professional association. Furthermore, 45 participants (46.9%) indicated that they either had no job guidelines or were unaware of such guidelines.

Table 2 presents the frequency, perceived importance, and correlation of clinical research nursing activities. The overall mean frequency score for the 52 activities was 2.02±1.27. The most frequently performed activity was “Collect data on research participant based on study endpoints (SM13)” (3.67±1.17), whereas the least frequently performed activity was “Serve as an IRB member (HSP5)” (0.46±0.79). The overall mean importance score was 2.91±1.24. The highest-rated activity in terms of importance was “Comply with International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Good Clinical Practice guidelines and Korean Good Clinical Practice guidelines (SM12)” (3.66±1.25), while the lowest-rated activity was “Serve as an expert in a specialty area (e.g., grant reviewer, editorial board, presenter, etc.) (CS2)” (1.89±1.35).

Correlation analysis showed that four activities exhibited no statistically significant relationship between frequency and importance: “Participate in study development” (r=.17, p=.094), “Participate in site visits and/or audits” (r=.17, p=.090), “Serve as an IRB member” (r=.07, p=.514), and “Disseminate clinical expertise and best practices related to clinical research through presentations, publications and/or interactions with nursing colleagues” (r=.18, p=.079). The remaining 48 activities demonstrated significant positive correlations.

The results by dimension are summarized in

Table 3. The CP dimension had the highest mean frequency (3.04±1.09), followed by SM (2.24±0.69), CCC (1.99±0.79), HSP (1.80±0.81), and CS (1.18±0.82). In terms of importance, the CP dimension again ranked highest (3.58±1.10), followed by SM (3.04±0.90), HSP (2.91±1.02), CCC (2.80±0.90), and CS (2.37±1.00). This ranking closely mirrored the frequency order.

Correlation analysis also indicated significant positive associations between frequency and importance across all five dimensions: CP (r=.66, p<.001), SM (r=.58, p<.001), CCC (r=.48, p<.001), HSP (r=.44, p<.001), and CS (r=.30, p=.003).

3. Differences in the Frequency of Clinical Research Nursing Activities across Five Dimensions according to Participants’ Characteristics

Differences in the frequency of clinical research nursing activities across the five dimensions according to participants’ characteristics are presented in

Table 4. Education level was significantly associated with differences in SM (F=5.32,

p=.007) and CS (F=3.72,

p=.028). Post hoc analysis indicated that participants with a master’s degree or higher reported significantly higher activity frequencies than those with an associate or bachelor’s degree. Marital status showed significant differences only in the HSP dimension (t=2.12,

p=.037), with single participants reporting higher activity frequencies than married or divorced participants. Annual salary demonstrated significant differences in SM (F=4.09,

p=.020) and CS (F=8.50,

p<.001). Participants with higher salaries reported greater involvement in these activities than those with lower salaries. Place of work was significantly associated with both CP (F=4.78,

p=.011) and CS (F=6.45,

p=.002). Participants working at research centers or private companies reported higher frequencies in CS activities compared to those at university hospitals. Employment type was significantly associated with differences in CP (F=5.99,

p=.004) and CS (F=13.20,

p<.001). Private employees reported significantly higher frequencies in CP compared to permanent employees. Clinical research experience was significantly associated with differences in CP (F=4.02,

p=.021) and CS (F=3.29,

p=.042). Participants with ≥5 years of experience reported higher frequencies in CP, whereas those with 3 to 5 years of experience reported higher frequencies in CS. The number of ongoing projects was significantly related to CP (F=7.95,

p<.001). Participants involved in more than six projects reported higher frequencies for CP than those involved in fewer projects. Clinical trial professional certification was associated with significant differences in CP (t=–2.10,

p=.039), HSP (t=2.15,

p=.034), and CS (t=5.46,

p<.001), with certified participants reporting higher frequencies for HSP and CS, but lower frequencies for CP. Affiliation with a relevant professional association was also significantly associated with differences in CP (t=–3.86,

p<.001) and CS (t=4.75,

p<.001), with affiliated participants reporting higher activity frequencies in CS, but lower activity frequencies in CP, than those without an affiliation. With respect to other variables, sex was excluded from the statistical analysis because the number of male participants was very small compared to females. In addition, age, region, and job guidelines were omitted from the results table because no significant differences were observed for these variables.

The IPA results are presented in

Figure 1. Clinical research nursing activities were distributed across all four quadrants, highlighting both areas of strength and those requiring targeted improvement.

1) Quadrant I (keep up the good work)

This quadrant included activities with high frequency and high importance. Most activities in the CP dimension (e.g., CP1, providing direct care; CP2, education; CP3, monitoring adverse events; CP4, recording data) and key activities in the SM dimension (e.g., SM3, screening participants; SM4, specimen collection; SM12, Good Clinical Practice compliance; SM13, endpoint data collection; SM16, data protection) were located here. In addition, several CCC activities (CCC3, CCC7, CCC9, CCC10) and HSP activities (HSP1, HSP2, HSP4) appeared in this quadrant, indicating that these core responsibilities are consistently performed and regarded as highly important in practice.

2) Quadrant II (concentrate here)

Activities with high importance but relatively low performance were placed in this quadrant, representing priority areas for improvement. Three SM activities—SM6 (quality assurance for data integrity), SM7 (regulatory reporting), and SM17 (site visits and audits)—were included, suggesting a need to strengthen competencies related to data quality assurance and regulatory compliance among CRNs.

3) Quadrant III (low priority)

This quadrant comprised activities rated low in both importance and frequency. Many SM activities (e.g., SM1, study development; SM5, participant education material development; SM18, budget development), CCC activities (e.g., CCC1, interdisciplinary team education; CCC5, interdisciplinary coordination), HSP activities (e.g., HSP3, ethical conflict resolution; HSP5, IRB membership), and CS activities (e.g., CS1, dissemination; CS2, expert role; CS8, secondary data analysis) were located here. These results suggest that these activities are viewed as peripheral to the primary responsibilities of CRNs within the Korean clinical research environment.

4) Quadrant IV (possible overkill)

Only one activity, SM2 (participant recruitment), appeared in this quadrant, indicating comparatively high performance relative to its perceived importance. This finding suggests that the level of effort or resources allocated to participant recruitment may exceed its relative value when compared with other essential areas.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first in Korea to systematically evaluate the frequency and perceived importance of 52 clinical research nursing activities across five dimensions and to apply IPA to identify key areas for improvement. The findings provide meaningful insights into the current status of CRN practice in Korea, with implications for education, policy development, and professional advancement.

Consistent with the findings of Bevans et al. [

9], this study showed that activities within the CP dimension were performed most frequently and were rated as most important. Activities such as direct patient care, participant education, adverse event monitoring, and research data documentation remained central to CRN practice in both contexts. This consistency reinforces that the core function of CRNs in Korea also lies in balancing protocol fidelity and participant protection, reflecting international trends emphasized in recent scoping reviews [

18]. In contrast, activities in the CS dimension were performed least often and were perceived as less important, mirroring international patterns. However, whereas Bevans et al. [

9] primarily presented overall role delineation, the present study advanced the analysis by applying IPA to prioritize improvement needs, thereby identifying specific dimensions requiring targeted intervention.

The analysis of participant characteristics revealed important trends. Higher education levels, professional certification, and membership in professional associations were significantly associated with greater activity frequencies across multiple dimensions. These findings underscore the value of formal education, certification processes, and active professional engagement in promoting CRN competencies. Such professionalization pathways serve as essential mechanisms that contribute to the systematic development of advanced research competencies in CRNs, enhancing their understanding of clinical trials, improving the accuracy of result interpretation, strengthening scientific rigor, and promoting the advancement of nursing science [

19]. Additionally, CRNs employed in university hospitals reported greater involvement in CP, whereas those in research centers or private companies showed higher engagement in CS, reflecting differing institutional roles and expectations. These variations highlight the need for training and policy support tailored to specific organizational contexts.

The IPA revealed strong performance in CP and selected SM activities, which is consistent with previous studies emphasizing the critical role of CRNs in participant management, safety monitoring, and protocol implementation [

19,

20]. CRNs occupy a unique position by simultaneously providing continuous nursing care to research participants and adhering rigorously to study protocols as part of the investigative team, a dual role documented in both earlier and more recent literature [

9,

18]. The high levels of performance in CP and SM activities observed in this study indicate successful implementation of these core CRN responsibilities in Korean clinical research settings. However, despite these strengths, Quadrant II (concentrate here) highlighted that quality assurance for data integrity, regulatory reporting, and site visits or audits were highly important yet underperformed. Quality-assurance activities are increasingly recognized as essential components of clinical trial quality management systems, playing a pivotal role in ensuring data consistency and participant safety [

21]. These findings indicate that Korean CRNs may face insufficient institutional support, limited training, or lack of authority to fully engage in these critical functions. This aligns with global challenges frequently reported by clinical trial professionals [

22]. Additionally, the lower involvement may reflect common role separation in clinical research operations, where specialized monitors or auditors often assume responsibility for such tasks rather than CRNs [

2]. Nevertheless, the high perceived importance of these functions among CRNs indicates a strong awareness of the centrality of quality assurance and regulatory compliance to research integrity. This recognition underscores the potential for CRNs to play an expanded role in research quality management. International studies have noted that CRNs increasingly serve as central figures in ensuring data integrity and compliance and have the potential to advance as key agents of research quality oversight [

19]. Therefore, targeted educational opportunities and supportive institutional policies are needed to enable CRNs to take a more active role in monitoring, quality assurance, and regulatory processes.

Activities in Quadrant III (low priority), such as IRB membership, dissemination of expertise, and budget development, were infrequently performed and regarded as peripheral to CRN practice. This phenomenon may reflect the reality that CRNs primarily focus on clinical research support and administrative management, leaving limited time and resources for academic or scientific activities that contribute to research advancement. Restricted awareness of such roles and limited opportunities for professional development may also contribute. Previous studies likewise reported that CRNs’ responsibilities center on clinical support and administrative tasks, with relatively low involvement in scientific or academic functions [

19,

20]. Furthermore, limited engagement in research decision-making and scholarly leadership reflects a broader global challenge in CRN professionalization, where constrained autonomy and ambiguous role definitions limit participation in strategic domains such as research ethics review [

18]. Although these activities may not be immediate priorities, expanding CRN involvement in dissemination and professional leadership may foster long-term role development and recognition. Participant recruitment (SM2), located in Quadrant IV (possible overkill), suggested potential inefficiencies in resource allocation, indicating a need for improved balance in workload distribution. While recruitment is a critical early step in the research process, excessive investment in recruitment tasks, even when successful, may signal an imbalanced workload. This aligns with findings that high workload and insufficient resource allocation contribute substantially to stress and high turnover among clinical trial professionals [

22]. Drawing on previous studies of general clinical nurses, where misalignment between assigned roles and actual tasks has been associated with reduced job satisfaction and diminished work efficiency [

23], organizational measures that enable CRNs to focus on core clinical research nursing activities as perceived by themselves may be beneficial. In accordance with the classic IPA framework proposed by Martilla and James [

17], institutions can enhance the overall quality of clinical trials and improve CRN retention by reallocating resources from over-invested areas.

The findings indicate that Korean CRNs are well positioned to provide direct clinical and research care but require additional training and institutional support in regulatory and data quality dimensions. Educational programs should integrate modules on Good Clinical Practice compliance as a foundation and must also cover data integrity assurance and regulatory reporting. Furthermore, certification and professional association membership should be promoted as mechanisms to enhance competencies and standardize CRN practice. At the policy level, establishing formal guidelines and role definitions specific to CRNs in Korea could reduce variability, strengthen quality assurance, and align domestic practice with international benchmarks. Ultimately, these tailored educational and policy interventions will strengthen CRN competencies and standardize practice, enabling CRNs to participate more actively in research governance and quality management systems, thereby safeguarding data integrity and participant safety [

18,

21].

This study has several limitations. First, the data were collected through an online survey of 96 CRNs in Korea, which restricts the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, the activity list used as the study instrument was originally developed in the United States and may not fully reflect the Korean clinical research environment. Future research should employ random sampling of CRNs across national research institutions and utilize face-to-face data collection methods to enhance the reliability and representativeness of the results. Furthermore, to more accurately define the unique activities and professional competencies of CRNs, it is necessary to identify activity items that are contextually appropriate for the Korean clinical research environment. Based on this need, the development of a domestically tailored clinical research nursing activity assessment tool is warranted.

CONCLUSION

This study is the first in Korea to systematically evaluate the frequency and perceived importance of 52 clinical research nursing activities across five dimensions and to apply IPA to identify key areas for improvement. The findings confirmed that CRNs play a central role in CP and SM while also revealing critical gaps in regulatory and quality assurance functions.

These results suggest that additional education, training, and institutional support are required to strengthen CRN competencies in areas such as compliance with ICH and Korean Good Clinical Practice guidelines, regulatory reporting, and data integrity assurance. Moreover, clinical trial professional certification and participation in professional associations were associated with higher performance across multiple dimensions, underscoring their importance as key contributors to advancing CRN professionalism.

Ultimately, this study clarified the activities of CRNs in Korea and proposed strategic directions for improvement, thereby providing foundational evidence for the advancement of CRN education, contributions to policy development, and the strengthening of professional identity. Defining the unique competencies and explicit roles of CRNs is essential for integrating nursing expertise into the clinical research environment, and further research, as well as broader recognition of CRN professionalism in Korea, are needed to achieve this goal.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and design - JYP; data acquisition and analysis - DSL and JYP; investigation - DSL and JYP; methodology - DSL and JYP; project administration - DSL and JYP; resources - DSL and JYP; software - DSL and JYP; supervision - DSL; validation - DSL and JYP; visualization - DSL and JYP; drafting and critical revision of the manuscript - DSL and JYP.

-

FUNDING

None.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Yeon Sook Kim (Department of Nursing, California State University, San Bernardino, CA, USA) supported the supervisor in translating the study measurement tool.

This article is based on a part of the Ji-Yeon Park’s master’s thesis from Kangwon National University.

-

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data can be obtained from the corresponding authors.

Figure 1.Importance–performance analysis of clinical research nursing activities. For description of each item (e.g., CP1), please refer to Table 2. CP=clinical practice; SM=study management; CCC=care coordination and continuity; HSP=human subjects protection; CS=contributing to the science.

Table 1.General Characteristics of the Participants (N=96)

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

n (%) |

M±SD |

|

Age (year) |

20–29 |

8 (8.3) |

32.81±6.91 |

|

30–39 |

58 (60.4) |

|

40–49 |

25 (26.0) |

|

50–59 |

5 (5.2) |

|

Sex |

Female |

91 (94.8) |

|

|

Male |

5 (5.2) |

|

Education level |

Associate degree |

10 (10.4) |

|

|

Bachelor |

73 (76.0) |

|

Master |

11 (11.5) |

|

Doctoral |

2 (2.1) |

|

Marital status |

Single |

34 (35.4) |

|

|

Married/divorced |

62 (64.6) |

|

Region |

Capital area |

75 (78.1) |

|

|

Noncapital area |

21 (21.9) |

|

Annual salary (₩10,000) |

<4,000 |

49 (51.0) |

|

|

4,000–4,999 |

39 (40.6) |

|

≥5,000 |

8 (8.3) |

|

Place of work |

University hospital |

70 (72.9) |

|

|

General hospital |

20 (20.8) |

|

Research center/private company |

6 (6.2) |

|

Employment type |

Permanent |

31 (32.3) |

|

|

Contract |

17 (17.7) |

|

Private |

48 (50.0) |

|

Clinical research experience (years) |

≥2 to <3 |

35 (36.5) |

|

|

≥3 to <5 |

30 (31.3) |

|

≥5 |

31 (32.3) |

|

Number of ongoing projects |

1–5 |

63 (65.6) |

5.24±4.51 |

|

6–10 |

23 (24.0) |

|

≥11 |

10 (10.4) |

|

Type of clinical research participated in |

Phase 1 |

23 (24.0) |

|

|

Phase 2 |

50 (52.1) |

|

Phase 3 |

62 (64.6) |

|

Phase 4 and PMS |

53 (55.2) |

|

Others |

45 (46.9) |

|

Clinical trial professional certification |

Yes |

24 (25.0) |

|

|

No |

72 (75.0) |

|

Affiliation with relevant professional association |

Yes |

23 (24.0) |

|

|

No |

73 (76.0) |

|

Job guideline |

Yes |

51 (53.1) |

|

|

No |

33 (34.4) |

|

Don’t know |

12 (12.5) |

Table 2.Frequency, Importance, and Correlations of Clinical Research Nursing Activities

|

Activities |

Frequency |

Importance |

r (p) |

|

M±SD |

|

Overall frequency and importance score |

2.02±1.27 |

2.91±1.24 |

|

|

Clinical practice |

|

|

|

|

1. Provide direct nursing care to research participants |

2.96±1.23 |

3.65±1.12 |

.37 (<.001) |

|

2. Provide teaching to research participants and family regarding study participation, participant’s current clinical condition, and/or disease process |

2.81±1.48 |

3.49±1.11 |

.55 (<.001) |

|

3. Monitor the research participant and report potential adverse events to a member of the research team |

2.90±1.28 |

3.55±1.20 |

.59 (<.001) |

|

4. Record research data (example: documentation of vital signs, administration of a research compound, participant responses, etc.) in approved source document (example: medical records, data collection sheets, etc.) |

3.51±1.41 |

3.61±1.31 |

.72 (<.001) |

|

Study management |

|

|

|

|

1. Participate in study development |

1.58±1.43 |

2.61±1.10 |

.17 (.094) |

|

2. Participate in research participant recruitment |

2.18±1.44 |

2.78±1.35 |

.51 (<.001) |

|

3. Participate in screening potential research participants for eligibility |

2.97±1.27 |

3.50±1.16 |

.62 (<.001) |

|

4. Coordinate and facilitate the collection of research specimens |

2.66±1.30 |

3.27±1.25 |

.54 (<.001) |

|

5. Develop study specific materials for research participant education |

1.61±1.26 |

2.79±1.15 |

.39 (<.001) |

|

6. Perform quality-assurance activities to assure data integrity |

1.43±1.30 |

3.00±1.20 |

.44 (<.001) |

|

7. Participate in the preparation of reports for appropriate regulatory and monitoring bodies/boards |

1.90±1.14 |

2.94±1.19 |

.47 (<.001) |

|

8. Facilitate accurate communication among research sites |

3.06±1.24 |

3.36±1.22 |

.56 (<.001) |

|

9. Facilitate communication within the research team |

3.31±1.21 |

3.57±1.11 |

.74 (<.001) |

|

10. Contribute to the development of case report forms |

1.11±1.20 |

2.59±1.29 |

.38 (<.001) |

|

11. Participate in the set-up of a study specific database |

1.20±1.33 |

2.36±1.27 |

.47 (<.001) |

|

12. Comply with International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) Good Clinical Practice guidelines and Korean Good Clinical Practice guidelines |

3.45±1.42 |

3.66±1.25 |

.74 (<.001) |

|

13. Collect data on research participant based on study endpoints |

3.67±1.17 |

3.64±1.15 |

.64 (<.001) |

|

14. Facilitate scheduling and coordination of study procedures |

2.25±1.60 |

3.08±1.26 |

.52 (<.001) |

|

15. Provide nursing expertise to the research team during study development and implementation |

2.22±1.42 |

3.07±1.04 |

.45 (<.001) |

|

16. Protect research participant data in accordance with regulatory requirements |

3.36±1.31 |

3.50±1.34 |

.72 (<.001) |

|

17. Participate in site visits and/or audits |

1.05±1.16 |

2.91±1.38 |

.17 (.090) |

|

18. Support study grant and budget development |

0.94±1.15 |

2.25±1.25 |

.32 (.002) |

|

19. Oversee human resources (people) related to research process |

1.14±1.19 |

2.49±1.21 |

.38 (<.001) |

|

20. Record data on approved study documents (Example: Case Report Forms, research/study database, etc.) |

3.48±1.44 |

3.63±1.34 |

.74 (<.001) |

|

21. Facilitate processing and handling (storage and shipping) of research specimens |

2.43±1.42 |

3.13±1.26 |

.55 (<.001) |

|

22. Identify clinical care implications during study development (example: staff competencies and resources, equipment, etc.) |

2.31±1.42 |

2.96±1.24 |

.56 (<.001) |

|

23. Participate in the identification and reporting of research trends |

2.10±1.17 |

2.94±1.18 |

.50 (<.001) |

|

Care coordination and continuity |

|

|

|

|

1. Facilitate the education of the interdisciplinary team on study requirements |

1.41±1.40 |

2.41±1.17 |

.28 (.005) |

|

2. Collaborate with the interdisciplinary team to create and communicate a plan of care that allows for safe and effective collection of clinical research data |

1.59±1.24 |

2.67±1.25 |

.55 (<.001) |

|

3. Coordinate research participant study visits |

3.24±1.41 |

3.51±1.24 |

.67 (<.001) |

|

4. Provide nursing leadership within the interdisciplinary team |

1.61±1.32 |

2.52±1.19 |

.44 (<.001) |

|

5. Coordinate interdisciplinary meetings and activities in the context of a study |

1.36±1.18 |

2.28±1.25 |

.38 (<.001) |

|

6. Coordinate referrals to appropriate interdisciplinary services outside the immediate research team |

1.49±1.22 |

2.35±1.23 |

.49 (<.001) |

|

7. Communicate the impact of study procedures on the research participants |

2.46±1.25 |

3.07±1.26 |

.50 (<.001) |

|

8. Provide nursing expertise to community-based health care personnel related to study participation |

1.13±1.29 |

2.40±1.24 |

.46 (<.001) |

|

9. Facilitate research participant inquiries and concerns |

2.95±1.11 |

3.47±1.09 |

.61 (<.001) |

|

10. Provide indirect nursing care (example: participation in clinical, unit, and/or protocol rounds; scheduling study related tests, etc.) in the context of research participation |

2.68±1.37 |

3.28±1.23 |

.58 (<.001) |

|

Human subjects protection |

|

|

|

|

1. Facilitate the initial and ongoing informed consent/assent process |

2.70±1.28 |

3.35±1.23 |

.58 (<.001) |

|

2. Support research participant in defining his/her reasons and goals for participating in a study |

2.71±1.32 |

3.20±1.28 |

.55 (<.001) |

|

3. Collaborate with the interdisciplinary team to address ethical conflicts |

1.45±1.25 |

2.78±1.22 |

.45 (<.001) |

|

4. Coordinate research activities to minimize subject risk |

2.17±1.40 |

3.18±1.19 |

.44 (<.001) |

|

5. Serve as an IRB member |

0.46±0.79 |

2.28±1.50 |

.07 (.514) |

|

6. Manage potential ethical and financial conflicts of interest for self |

1.33±1.14 |

2.66±1.35 |

.47 (<.001) |

|

Contributing to the science |

|

|

|

|

1. Disseminate clinical expertise and best practices related to clinical research through presentations, publications and/or interactions with nursing colleagues |

1.08±1.40 |

2.25±1.29 |

.18 (.079) |

|

2. Serve as an expert in a specialty area (example: grant reviewer, editorial board, presenter, etc.) |

0.54±0.88 |

1.89±1.35 |

.25 (.015) |

|

3. Participate in the query and analysis of research data |

2.14±1.48 |

2.94±1.34 |

.55 (<.001) |

|

4. Generate practice questions as a result of a new study procedure or intervention |

1.54±1.24 |

2.57±1.19 |

.40 (<.001) |

|

5. Collaborate with the interdisciplinary team to develop innovations in care delivery that have the potential to improve patient outcomes and accuracy of data collection |

1.10±1.23 |

2.33±1.19 |

.29 (.004) |

|

6. Identify questions appropriate for clinical nursing research as a result of study team participation |

0.90±1.21 |

2.06±1.22 |

.29 (.004) |

|

7. Mentor junior staff and students participating as members of the research team |

1.35±1.26 |

2.85±1.31 |

.40 (<.001) |

|

8. Perform secondary data analysis to contribute to the development of new ideas |

0.69±1.01 |

2.02±1.25 |

.26 (.009) |

|

9. Serve as a resource to new investigators |

1.27±1.20 |

2.44±1.30 |

.41 (<.001) |

Table 3.Frequency, Importance, and Correlations of Clinical Research Nursing Practice Dimensions

|

Clinical research nursing practice dimension |

Frequency |

Importance |

r (p) |

|

M±SD |

|

Clinical practice |

3.04±1.09 |

3.58±1.10 |

.66 (<.001) |

|

Study management |

2.24±0.69 |

3.04±0.90 |

.58 (<.001) |

|

Care coordination and continuity |

1.99±0.79 |

2.80±0.90 |

.48 (<.001) |

|

Human subjects protection |

1.80±0.81 |

2.91±1.02 |

.44 (<.001) |

|

Contributing to the science |

1.18±0.82 |

2.37±1.00 |

.30 (.003) |

Table 4.Differences in the Frequency of Clinical Research Nursing Activities across Five Dimensions according to Participants’ Characteristics

|

Characteristics |

Categories |

n (%) |

Clinical practice |

Study management |

Care coordination and continuity |

Human subjects protection |

Contributing to the science |

|

M±SD |

F/t |

p (Duncan) |

M±SD |

F/t |

p (Duncan) |

M±SD |

F/t |

p (Duncan) |

M±SD |

F/t |

p (Duncan) |

M±SD |

F/t |

p (Duncan) |

|

Education level |

Associate degreea

|

10 (10.4) |

3.08±1.21 |

0.23 |

.793 |

1.85±0.40 |

5.32 |

.007 (a, b<c) |

1.76±0.51 |

1.64 |

.200 |

1.35±0.58 |

2.80 |

.066 |

0.83±0.65 |

3.72 |

.028 (a<c) |

|

Bachelorb

|

73 (76.0) |

3.01±1.15 |

|

|

2.20±0.67 |

|

|

1.96±0.82 |

|

|

1.80±0.82 |

|

|

1.14±0.81 |

|

|

|

Master or higherc

|

13 (13.6) |

3.23±0.66 |

|

|

2.73±0.81 |

|

|

2.32±0.72 |

|

|

2.14±0.78 |

|

|

1.69±0.85 |

|

|

|

Marital status |

Single |

34 (35.4) |

3.18±1.10 |

0.88 |

.383 |

2.33±0.73 |

1.00 |

.319 |

2.18±0.88 |

1.71 |

.090 |

2.03±0.89 |

2.12 |

.037 |

1.38±0.79 |

1.78 |

.078 |

|

Married/divorced |

62 (64.6) |

2.97±1.09 |

|

|

2.18±0.68 |

|

|

1.89±0.72 |

|

|

1.67±0.74 |

|

|

1.07±0.83 |

|

|

|

Annual salary (₩10,000) |

<4,000a

|

49 (51.0) |

2.97±1.15 |

0.50 |

.608 |

2.04±0.61 |

4.09 |

.020 |

1.82±0.74 |

2.59 |

.081 |

1.65±0.75 |

1.73 |

.183 |

0.87±0.73 |

8.50 |

<.001 (a<b, c) |

|

4,000–4,999b

|

39 (40.6) |

3.17±1.01 |

|

|

2.44±0.76 |

|

|

2.19±0.83 |

|

|

1.97±0.88 |

|

|

1.45±0.82 |

|

|

|

≥5,000c

|

8 (8.3) |

2.84±1.20 |

|

|

2.39±0.62 |

|

|

2.10±0.71 |

|

|

1.92±0.70 |

|

|

1.74±0.65 |

|

|

|

Place of work |

University hospitala

|

70 (72.9) |

3.25±1.09 |

4.78 |

.011 |

2.29±0.72 |

2.43 |

.093 |

2.01±0.84 |

0.32 |

.729 |

1.76±0.87 |

1.40 |

.252 |

1.02±0.75 |

6.45 |

.002 (a<c) |

|

General hospitalb

|

20 (20.8) |

2.49±0.94 |

|

|

1.96±0.58 |

|

|

1.88±0.63 |

|

|

1.79±0.66 |

|

|

1.52±0.85 |

|

|

|

Research center/private companyc

|

6 (6.2) |

2.54±0.97 |

|

|

2.54±0.53 |

|

|

2.12±0.78 |

|

|

2.33±0.33 |

|

|

1.96±0.89 |

|

|

|

Employment type |

Permanenta

|

31 (32.3) |

2.54±0.76 |

5.99 |

.004 (a<c) |

2.21±0.60 |

0.56 |

.572 |

1.98±0.61 |

0.21 |

.811 |

1.97±0.60 |

1.07 |

.346 |

1.73±0.77 |

13.20 |

<.001 (a>b, c) |

|

Contractb

|

17 (17.7) |

3.04±1.20 |

|

|

2.10±0.81 |

|

|

1.89±0.81 |

|

|

1.67±0.95 |

|

|

0.98±0.65 |

|

|

|

Privatec

|

48 (50.0) |

3.37±1.13 |

|

|

2.30±0.72 |

|

|

2.03±0.89 |

|

|

1.74±0.87 |

|

|

0.89±0.74 |

|

|

|

Clinical research experience (year) |

≥2 to <3a

|

35 (36.5) |

2.79±1.17 |

4.02 |

.021 (a, b<c) |

2.12±0.66 |

0.90 |

.411 |

1.83±0.85 |

1.46 |

.238 |

1.71±0.80 |

0.63 |

.535 |

1.01±0.82 |

3.29 |

.042 (a, c<b) |

|

≥3 to <5b

|

30 (31.3) |

2.89±1.02 |

|

|

2.25±0.65 |

|

|

2.16±0.64 |

|

|

1.93±0.68 |

|

|

1.49±0.82 |

|

|

|

≥5c

|

31 (32.3) |

3.48±0.96 |

|

|

2.35±0.77 |

|

|

2.02±0.85 |

|

|

1.78±0.94 |

|

|

1.07±0.77 |

|

|

|

No. of ongoing projects |

1–5a

|

63 (65.6) |

2.75±1.14 |

7.95 |

<.001 (a<b, c) |

2.12±0.65 |

2.66 |

.075 |

1.90±0.75 |

1.36 |

.262 |

1.73±0.74 |

2.45 |

.092 |

1.31±0.85 |

2.73 |

.070 |

|

6–10b

|

23 (24.0) |

3.67±0.76 |

|

|

2.50±0.83 |

|

|

2.20±0.98 |

|

|

2.11±0.93 |

|

|

1.02±0.79 |

|

|

|

≥11c

|

10 (10.4) |

3.48±0.67 |

|

|

2.33±0.49 |

|

|

2.12±0.44 |

|

|

1.55±0.81 |

|

|

0.73±0.45 |

|

|

|

Clinical trial professional certification |

Yes |

24 (25.0) |

2.65±1.15 |

–2.10 |

.039 |

2.26±0.84 |

0.18 |

.858 |

2.12±0.79 |

0.92 |

.358 |

2.10±0.71 |

2.15 |

.034 |

1.88±0.72 |

5.46 |

<.001 |

|

No |

72 (75.0) |

3.18±1.05 |

|

|

2.23±0.65 |

|

|

1.95±0.79 |

|

|

1.70±0.82 |

|

|

0.95±0.72 |

|

|

|

Affiliation with relevant professional association |

Yes |

23 (24.0) |

2.47±0.70 |

–3.86 |

<.001 |

2.20±0.51 |

–0.31 |

.757 |

2.13±0.55 |

1.00 |

.322 |

1.98±0.61 |

1.20 |

.234 |

1.82±0.67 |

4.75 |

<.001 |

|

No |

73 (76.0) |

3.23±1.14 |

|

|

2.25±0.75 |

|

|

1.95±0.85 |

|

|

1.75±0.86 |

|

|

0.98±0.76 |

|

|

REFERENCES

- 1. National Institutes of Health. NIH policy and guidelines on the inclusion of women and minorities as subjects in clinical research [Internet]. Bethesda, MD: NIH; 2025 [cited 2025 October 23]. Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/policy/inclusion/women-and-minorities/guidelines.htm

- 2. Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (KR). Korean good clinical practice [Internet]. Cheongju: MFDS; 2022. [cited 2025 October 23]. Available from: https://portal.scourt.go.kr/pgp/main.on?w2xPath=PGP1021M04&jisCntntsSrno=2025000005522&c=900#000400E

- 3. Korea National Enterprise for Clinical Trials. 2024 Korea clinical trials white paper [Internet]. Seoul: Korea National Enterprise for Clinical Trials; 2024. [cited 2025 May 28]. Available from: https://www.konect.or.kr/kr/board/konect_library_02/boardList.do

- 4. Korean Association of Clinical Research Coordinator. 2021 CRC operational status, workload, and job satisfaction survey. Korea Assoc Clin Res Coordinator. 2022;16:10-15.

- 5. Jeong IS. 2017 domestic CRC manpower survey and job change analysis. Seoul: Korea National Enterprise for Clinical Trials; 2017. p. 67-68.

- 6. Korea Food and Drug Administration; National Institute of Toxicological Research. Basic education for those involved in clinical trials: research nurse (CRC). Seoul: Korea Food and Drug Administration; 2005. p. 15-26.

- 7. American Nurses Association; International Association of Clinical Research Nurses. Clinical research nursing: scope and standards of practice. Silver Spring, MD: American Nurses Association; 2016. p. 2-19.

- 8. National Institutes of Health (US) Clinical Center. Clinical Research Nursing: domain of practice [Internet]. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health (US) Clinical Center; 2009. [cited 2025 October 23]. Available from: https://www.cc.nih.gov/nursing/crn/2010

- 9. Bevans M, Hastings C, Wehrlen L, Cusack G, Matlock AM, Miller-Davis C, et al. Defining clinical research nursing practice: results of a role delineation study. Clin Transl Sci. 2011;4(6):421-7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00365.x

- 10. International Association of Clinical Research Nurses. About IACRN [Internet]. Mullica Hill, NJ: International Association of Clinical Research Nurses; 2025 [cited 2025 October 23]. Available from: https://www.iacrn.org/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=34:about-us&catid=20:site-content&Itemid=127

- 11. McCabe M, Ness E. Clinical research nursing core curriculum. Mullica Hill, NJ: International Association of Clinical Research Nurses; 2021. p. 16.

- 12. Do SJ. The role of clinical research nurses at regional clinical trials centers. J Korean Acad Nurs Adm. 2010;16(3):348-59. https://doi.org/10.11111/jkana.2010.16.3.348

- 13. Hwang YS. Job analysis of clinical research nurse in oncology department. Korea Clin Res Coordinator Assoc. 2008;(2):20-38.

- 14. Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39(2):175-91. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03193146

- 15. American Nurses Association; International Association of Clinical Research Nurses. Clinical research nursing: scope and standards of practice. La Vergne, TN: American Nurses Association; 2016. p. 16-20.

- 16. Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011. p. 60.

- 17. Martilla JA, James JC. Importance-performance analysis. J Mark. 1977;41(1):77-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224297704100112

- 18. Bozzetti M, Guberti M, Lo Cascio A, Privitera D, Genna C, Rodelli S, et al. Uncovering the professional landscape of clinical research nursing: a scoping review with data mining approach. Nurs Rep. 2025;15(8):266. https://doi.org/10.3390/nursrep15080266

- 19. Xing Y, Wang X, Zhang C, Yuan W, Chen X, Luan W. Characteristics and duties of clinical research nurses: a scoping review. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1333230. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1333230

- 20. Hastings CE, Fisher CA, McCabe MA; National Clinical Research Nursing Consortium, Allison J, Brassil D, Offenhartz M, et al. Clinical research nursing: a critical resource in the national research enterprise. Nurs Outlook. 2012;60(3):149-56. e1-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2011.10.003

- 21. B P, Kothapalli P, Vasanthan M. The role of quality assurance in clinical trials: safeguarding data integrity and compliance. Cureus. 2024;16(8):e67573. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.67573

- 22. Peralta G, Sanchez-Santiago B. Navigating the challenges of clinical trial professionals in the healthcare sector. Front Med (Lausanne). 2024;11:1400585. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2024.1400585

- 23. Kim J, Lee E, Kwon H, Lee S, Choi H. Effects of work environments on satisfaction of nurses working for integrated care system in South Korea: a multisite cross-sectional investigation. BMC Nurs. 2024;23(1):459. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-024-02075-9