Abstract

-

Purpose

The incidence of diabetes mellitus (DM) rises significantly in the post-middle-age population, and stress along with depressive symptoms hinders effective DM management. This study examined the mediating effect of social capital (trust in the physical environment, reciprocity, social participation, and social networks) on the relationship between perceived stress and depression among middle-aged adults with DM in Korea. It also aimed to provide data for developing targeted interventions to enhance blood glucose management in this population.

-

Methods

A descriptive correlational study using data from the 2019 Community Health Survey by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) was conducted. Complex sample regression analysis and the Sobel test were employed for mediation analysis. The study included 9,394 middle-aged adults (aged 45-64 years) diagnosed with DM. The analysis assessed the effects of perceived stress on social capital and depression, as well as the mediating role of social capital.

-

Results

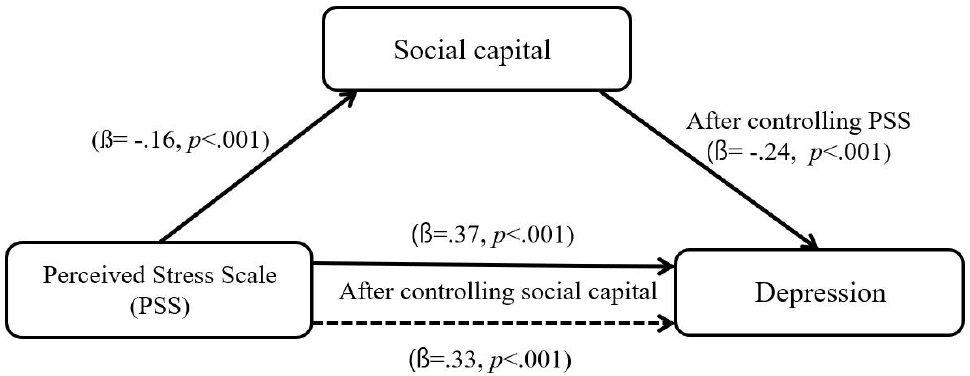

Perceived stress negatively impacted social capital (β=-0.16, p<.001) and positively influenced depression (β=0.37, p<.001). Both perceived stress and social capital significantly affected depression (F=998.83, p<.001), with social capital showing a partial mediating effect (z=2.65, p<.001).

-

Conclusion

Social capital partially mediated the relationship between stress and depression, suggesting its potential as a strategy for reducing stress and lowering depression among middle-aged adults with DM. These findings lay the groundwork for targeted interventions to improve blood glucose management in this population. Future research should explore the relationships among specific components of social capital, stress, and depression.

-

Key Words: Depression; Diabetes mellitus; Middle aged; Perceived stress scale; Social capital

INTRODUCTION

Globally, more than 500 million individuals are diagnosed with Diabetes Mellitus (DM), a figure projected to double to 1.3 billion within the next 30 years. Currently, DM affects approximately 6.1% of the global population [

1]. The prevalence of DM begins to rise during middle adulthood and increases dramatically after the age of 65 years [

1]. DM is a leading cause of premature death and disability [

1,

2]. In South Korea, the prevalence of diabetes among adults was 11.2% for men and 6.9% for women as of 2022. Prevalence increases with age for both sexes, and the incidence of diabetes requiring management among middle-aged individuals rose significantly, particularly in those aged 50~59 years, where it reached 30.1% for men and 19.1% for women [

3,

4]. DM significantly contributes to global mortality; therefore, while prevention is critical, effective management after diagnosis is equally important [

5]. Middle-aged adults (aged 40~59 years) are known to experience the highest levels of stress worldwide [

6]. As a result, they are at increased risk of suicide, sleep disturbances, alcohol dependence, impaired concentration and memory, job-related stress, headaches, and depression [

6]. Chronic stress adversely affects metabolic functions by increasing catecholamine release and serum glucocorticoid concentrations [

7]. These physiological changes can elevate insulin resistance and trigger hyperglycemia in individuals with DM [

7]. Furthermore, chronic stress is a well-established risk factor for depression [

8], and middle-aged adults are twice as likely to experience depression compared with those younger than 25 or aged 60 years and above [

6]. Depression among individuals with diabetes further undermines glycemic control, while emotional support from social networks has been shown to reduce depressive symptoms and promote self-management skills in middle-aged adults [

9,

10].

Social capital, which encompasses trust, reciprocity, social participation, and social networks, plays a critical role in reducing stress and depression [

11] and can serve as a protective factor against these psychological challenges [

12]. Therefore, understanding the interplay among stress, depression, and social capital is essential for promoting the psychological and social well-being of middle-aged individuals with diabetes.

Despite these insights, research on social capital among middle-aged adults with diabetes has primarily focused on its relationship with depression [

13,

14] and on identifying its determinants [

15]. There is a notable gap in studies confirming whether social capital mediates the relationship between perceived stress and depression in this population. Therefore, this study aimed to explore the relationships among stress, depression, and social capital-factors that influence blood glucose control in individuals with DM-and to determine whether social capital mediates the relationship between stress and depression. The findings are expected to provide foundational data for developing interventions to alleviate stress and depression that impede blood glucose management in middle-aged adults with DM.

METHODS

1. Study Design

This descriptive correlational study investigated the mediating effect of social capital (trust in the physical environment, reciprocity, social participation, and social networks) on the relationship between perceived stress and depression among middle-aged adults with DM in Korea.

2. Participants

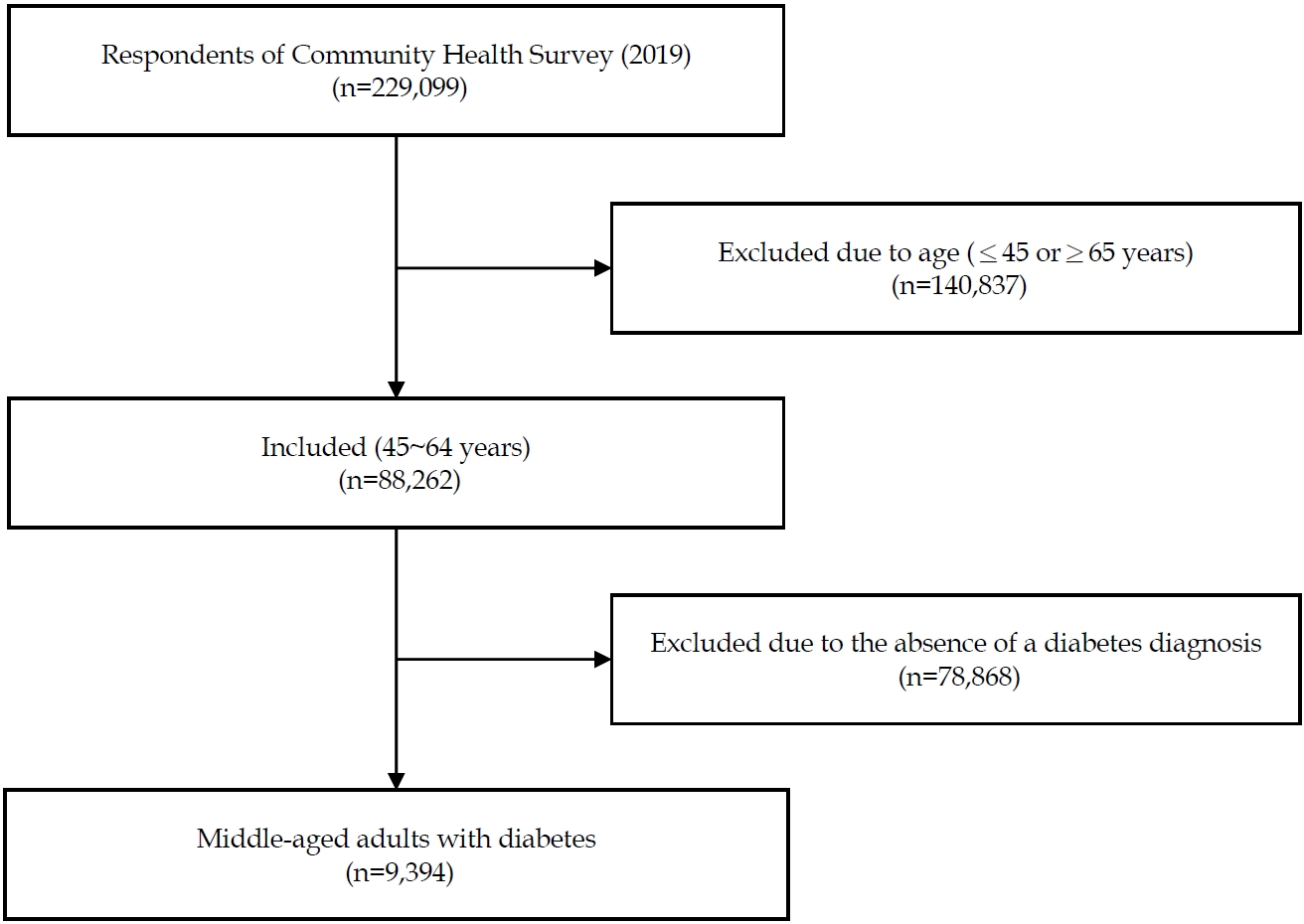

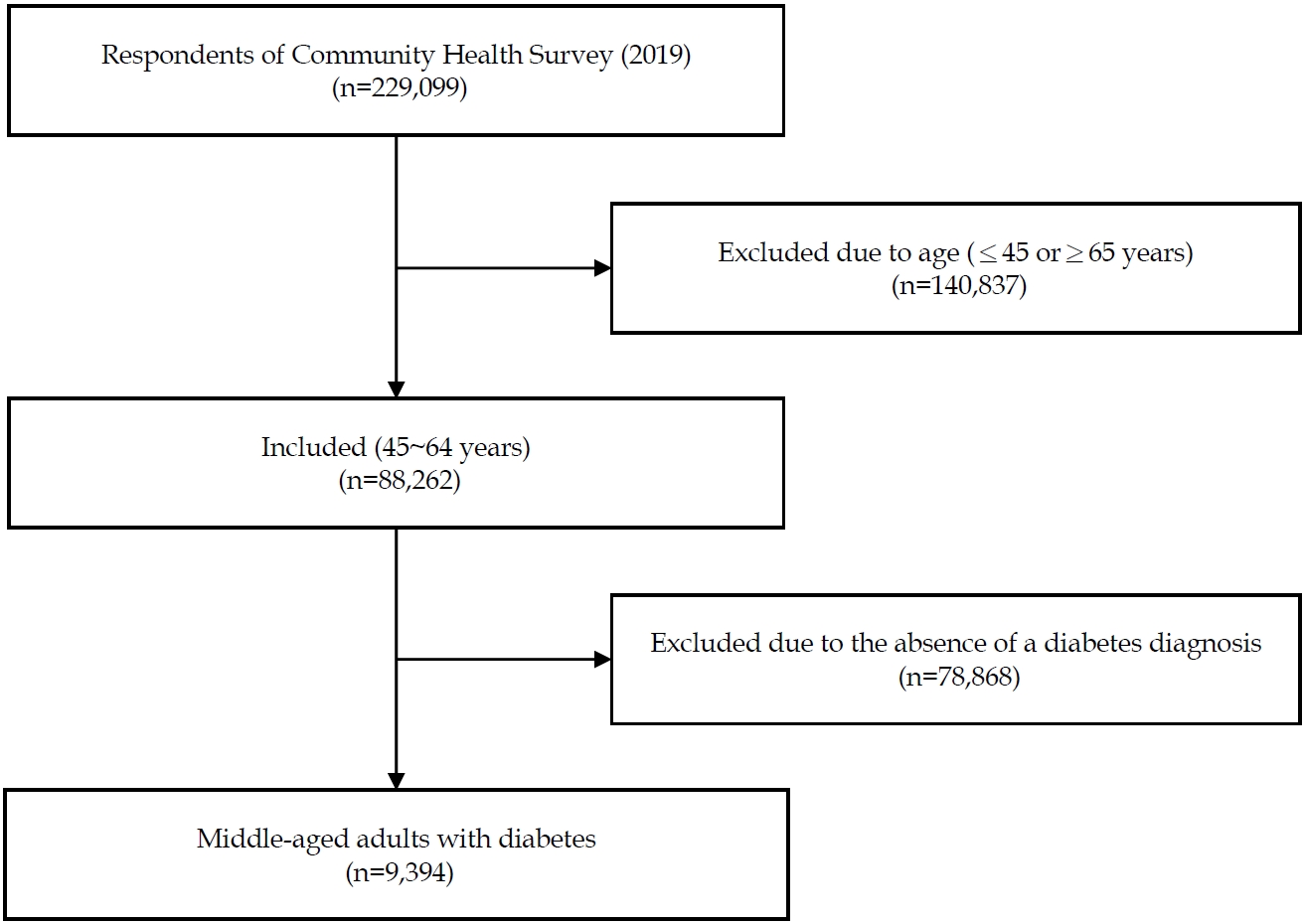

To examine the health status of community residents in Korea and provide foundational data for healthcare policies, we used raw data from the 2019 Community Health Survey (CHS) conducted by the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA).

Adults aged ≥19 years were included as the target population. Initially, an average of 900 individuals from each public health center were selected and proportionally sampled by dong, eup, and myeon (neighborhood, town, and township, respectively). The sampling was stratified by housing type and the number of households, using a probability proportional to size method for the first stage and systematic sampling for the second stage, resulting in a total sample of 229,099 individuals. The sample was further stratified by dong/eup/myeon (neighborhood/town/ township) in 17 metropolitan areas and by housing type. For this study, we selected 88,262 middle-aged adults aged 45~64 years, and ultimately, 9,394 individuals diagnosed with DM and undergoing treatment for DM were included (

Figure 1).

1) General characteristics

This study focused on middle-aged individuals (aged 45~64 years) and examined general characteristics including education, occupation, monthly income, marital status, and lifestyle choices (e.g., drinking and smoking). Household monthly income was categorized into quintiles based on the 2020 data from Statistics Korea, with the highest quintile labeled as "high" and the lowest as "low." In addition, we assessed factors such as DM treatment modality, participation in DM management education, and awareness of blood sugar and blood pressure levels.

2) Perceived stress scale

The perceived stress score is a derived variable established under the supervision of the KDCA to ensure reliability. It was calculated as the proportion of respondents who reported feeling "extremely stressed" or "highly stressed" in their daily lives relative to the total number of respondents. Previous studies have reported a Cronbach's α of 0.92 for this scale, indicating high reliability [

16].

3) Depression

Depression was measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), which consists of nine items. Participants indicated the frequency of each symptom experienced over the past two weeks, with each item rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 ("never") to 3 ("almost every day"). The total score ranges from 0 to 27. Based on a cut-off score of 10 [

17], scores were classified as follows: 0~4 indicating no symptoms, 5~9 indicating mild depression, and 10 or higher indicating moderate or more severe depression [

18]. In this study, the PHQ-9 demonstrated a Cronbach's α coefficient of 0.82, comparable to the 0.83 reported in previous research [

19].

4) Social capital

Social capital refers to collaboration, communication, and problem-solving among members of a society. Based on Putnam's definition (1995) [

20,

21], we selected the following components as indicators of social capital: trust in the physical environment, reciprocity, social participation, and social networks [

22]. These variables were measured using data on the social and physical environment from the 2019 CHS.

Trust in the community's physical environment was assessed using two items: "People in our neighborhood can be trusted" and "People in our neighborhood help each other during family events." Reciprocity was measured using five items: satisfaction with overall neighborhood safety, the natural environment (including air and water quality), the living environment (covering electricity, water and sewage, garbage collection, and sports facilities), the convenience of public transport, and satisfaction with healthcare services; each item was recorded as a "yes" or "no." Social participation was measured in four areas (religious activities, social activities, leisure/recreational activities, and charitable organizations) by assigning a value of 1 for regular participation (at least once a month) and 0 otherwise. Social networks were assessed using three items regarding the frequency of contact with closest neighbors, friends, or relatives, with a score of 1 indicating contact at least once a month and 0 for less frequent contact [

23]. The scores for these components were summed to yield a total social capital score ranging from 0 to 14, with higher scores indicating more positive social capital. In this study, the Cronbach's α coefficient for social capital was 0.78, compared to 0.91 in a previous study [

24].

The raw data were collected through a collaborative effort involving the KDCA, 17 metropolitan cities, 255 public health centers, and 35 designated universities and organizations. A management office was established to oversee the data collection, which occurred from August 16, 2019, to October 31, 2019. Trained interviewers conducted face-to-face surveys by visiting selected households. To safeguard personal information, only de-identified data were provided, in accordance with the Statistics Act. The data collection process was approved by Statistics Korea (Approval number 117075).

5. Ethical Considerations

The CHS is conducted to provide data for establishing and evaluating community healthcare plans in accordance with Article 4 (Community Health Survey) of the Regional Public Health Act and Article 2 (Methods and Content of Community Health Surveys) of the Enforcement Decree of the Regional Public Health Act. The authors obtained permission to use the 2019 CHS raw data after completing the necessary approval process available on the KDCA's CHS website (

https://chs.kdca.go.kr/chs/mnl/mnlBoardMain.do). Additionally, the authors reviewed the "CHS raw data analysis manual" prior to using the data. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kyungdong University approved the secondary data analysis (IRB No: 1041455-202106-HR-007-01).

A three-step regression analysis method, as proposed by Baron and Kenny [

25], was employed to examine the mediating effect of social capital on the relationship between perceived stress levels and depression among middle-aged individuals with diabetes in Korea.

In the first step, the effect of the independent variable (perceived stress) on the dependent variable (depression) was assessed. In the second step, we examined the effect of the independent variable on the mediator (social capital). In the third step, both the independent variable and the mediator were included simultaneously to assess their effects on the dependent variable.

The statistical significance of the mediating effect was evaluated using the Sobel test, which tests the indirect effect by incorporating the regression coefficients and their standard errors. The Sobel test is widely used in social and behavioral sciences for mediation analysis. Regression coefficients (beta values) and standard errors from steps one and three were input into the Sobel test formula (accessible at

http://www.quantpsy.org/sobel/sobel.htm).

Additional criteria were applied to confirm the robustness of the findings, including verifying that the independent variable significantly affected the mediator in step two and that the inclusion of the mediator in step three reduced the direct effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. These conditions were used to determine whether the mediation was full or partial. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with a significance level of p<.05.

RESULTS

1. Participants' General Characteristics

The study included 5,251 men (55.9%) and 4,143 women (44.1%), with a mean age of 57.29±5.19 years. The most common family income bracket was middle-low (n=2,869, 37.7%). Regarding alcohol consumption, 2,263 participants (37.9%) reported drinking alcohol more than twice a week, and 2,512 participants (52.2%) were either never smokers or former smokers. Most participants were aware of their blood sugar levels (7,163, 76.3%) and their blood pressure readings (7,011, 74.6%). Only 2,213 participants (23.6%) had received DM education. In terms of self-rated health, 4,366 participants (46.5%) reported their health as average, while 3,518 (37.4%) described it as poor (

Table 1).

The mean perceived stress score was 0.26±0.44. Mild depressive symptoms were present in 11.9% of participants (n=1,118), while 396 participants (4.2%) met the criteria for clinical depression. In terms of social capital, 6,218 participants (71.0%) expressed satisfaction with the level of trust in their neighbors, 7,865 (84.0%) with the reciprocity of the living environment, 6,704 (72.9%) with transportation, and 6,753 (72.9%) with healthcare services. Regarding social participation, 2,673 participants (28.5%) engaged in religious activities, and 1,090 (11.6%) participated in social activities. Additionally, 7,931 participants (84.5%) reported having regular contact with their family (

Table 2).

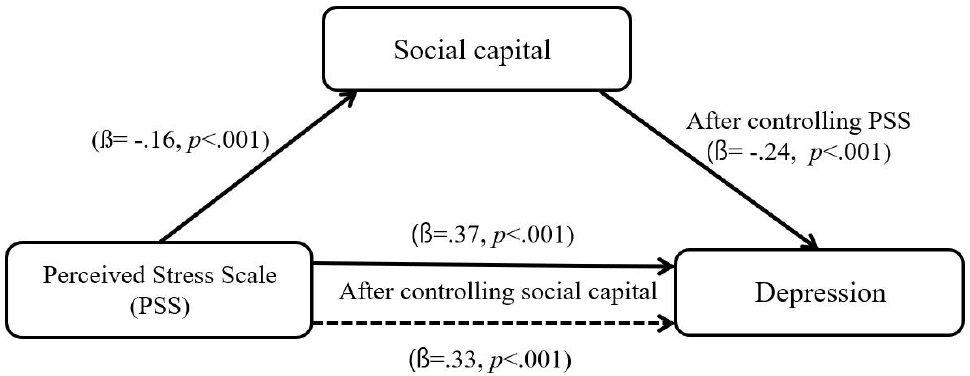

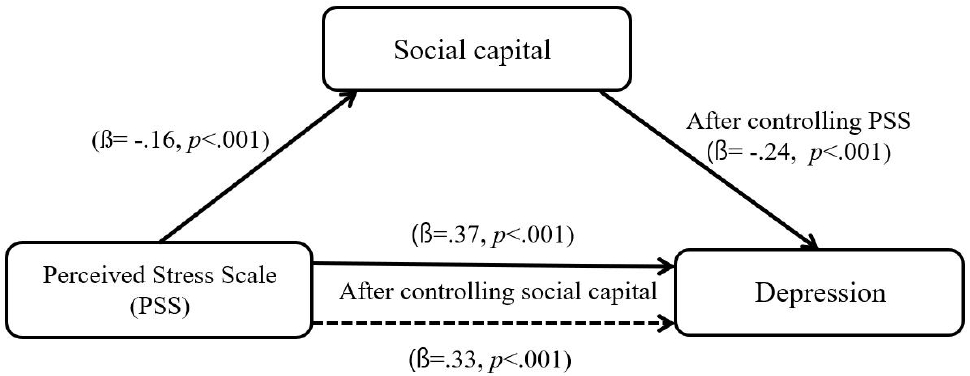

Following the three-step mediation regression analysis by Baron and Kenny [

25], the first step revealed that perceived stress (the independent variable) significantly affected social capital (the mediator) (β=-.16,

p<.001), thereby satisfying the first condition (

Figure 2). In the second step, perceived stress significantly affected depression (the dependent variable) (β=.37,

p<.001). In the third step, both perceived stress and social capital were entered into a hierarchical regression analysis. The results indicated that perceived stress continued to significantly affect depressive symptoms, with the absolute β value decreasing from .37 to .33 and the explained variance increasing from 13% to 19% (F=998.83,

p<.001), thus satisfying the third condition. The Sobel test confirmed that social capital partially mediated the relationship between perceived stress and depression, with a Z coefficient of 2.65 (l Z l >1.96), indicating a significant mediating effect (

Table 3).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of DM among middle-aged individuals in Korea has been steadily increasing each year [

4]. This study examined the mediating role of social capital in the relationship between stress and depression, both of which serve as significant barriers to effective blood glucose management. These findings provide a critical foundation for designing evidence-based interventions to improve glycemic control in middle-aged patients with DM. Stress, depression, and social capital are key factors that collectively influence both the psychosocial and physiological health of middle-aged patients with DM [

9]. Depression is a common comorbidity in this population, occurring at significantly higher rates than in the general population, which exacerbates the psychological burden on patients [

26]. Our analysis indicated that 16.1% of middle-aged patients with DM experienced severe depressive symptoms, compared with 11.2% of individuals without DM [

27]. This finding suggests that depression is more prevalent among patients with diabetes, with primary causes including chronic stressors such as the ongoing burden of disease management, fear of complications, and financial strain [

28]. A systematic review has shown that chronic stress interferes with glycemic control, increases the risk of hyperglycemia, and negatively affects mental health [

7]. Furthermore, a 35-year cohort study in Sweden reported that sustained stress increased the likelihood of DM onset by 42.6%, underscoring the need for effective stress mitigation in DM care [

29].

Social capital, which includes trust, reciprocity, and social networks, emerged as a crucial factor in mitigating the adverse effects of stress and depression. Our results revealed that higher stress levels were associated with lower social capital scores, which in turn correlated with increased depression. These findings are consistent with previous research involving 152 Korean patients with DM, which demonstrated a strong association between elevated stress levels and higher depression scores [

30]. Similarly, a study of 1,761 Chinese patients with DM found an inverse relationship between social capital and depression [

13,

31]. Higher levels of social trust and community support were associated with better glycemic control and improved mental health outcomes, as reported in earlier studies [

32]. Moreover, cognitive social capital-characterized by shared values and trust within communities-was found to positively influence both depressive symptoms and blood glucose regulation [

14].

Despite the benefits of social capital, only 65.0% of middle-aged patients with DM actively participated in social gatherings. Participation in religious activities (28.5%), leisure activities (28.5%), and charitable activities (11.6%) was considerably lower. This limited engagement indicates a need for interventions that foster broader social participation to alleviate stress and improve psychological wellbeing. These results are supported by a cross-sectional survey of 1,747 patients with DM, which reported that depression mediated the relationship between neighborhood cohesion and life satisfaction [

33]. A scientific review further emphasized that social support can mitigate the effects of poor health, promote physical well-being, and enhance overall life satisfaction through active participation in social cohesion activities. Additionally, declining social and physical environments were correlated with increased DM prevalence, underscoring the critical role of social capital in comprehensive DM management [

34]. It is important to note that the relationships among social capital, stress, and depression may vary depending on social context and the methods used to measure social capital [

35]. Future research should explore these interactions in diverse settings to better understand these differences.

The mediating role of social capital in the relationship between stress and depression is critical for improving the health outcomes of middle-aged patients with DM. These findings underscore the need for national-level initiatives to strengthen social capital and implement targeted stress management programs. Such strategies could significantly enhance both the quality of life and glycemic outcomes for this vulnerable population. This study utilized a secondary data analysis approach, including participants with a confirmed diagnosis of DM who were actively managing their blood glucose levels through insulin therapy, oral antidiabetic agents, or lifestyle modifications. Future research should examine the interrelationships among stress, depression, and social capital, with a specific focus on distinguishing between individuals with type 1 and type 2 DM.

CONCLUSION

This study investigated the effects of social capital on the relationship between perceived stress and depression in middle-aged adults (aged 45~64 years) with DM. Both perceived stress and social capital emerged as significant predictors of depression, with social capital partially mediating the effect of stress on depression. In addition, depression was found to increase with higher levels of perceived stress and lower social capital scores. These findings suggest that enhancing social networks, promoting social participation, and fostering trust in the physical environment may be effective strategies for reducing depression in middle-aged adults with DM.

Future research should examine the specific mechanisms by which different components of social capital influence the stress-depression pathway, conduct longitudinal studies to establish temporal relationships, and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed to enhance social capital in reducing depression within this population.

-

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

-

AUTHORSHIP

Study conception and design acquisition - KKA and BMR; analysis - KKA; interpretation of the data - KKA and BMR; and drafting or critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content - KKA and BMR.

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

This study was supported by Kyungdong University Research Fund, 2021.

Figure 1.Flow chart of the study population.

Figure 2.Mediating effect of social capital on depression in Korean middle-aged adults with diabetes.

Table 1.General Characteristics of Participants (N=9,394)

|

Variables |

Categories |

n (%) or |

|

M±SD |

|

Age (year) |

|

57.29±5.19 |

|

Sex |

Men |

5,251 (55.9) |

|

Women |

4,143 (44.1) |

|

Living with |

Spouse or Children |

7,427 (79.1) |

|

Divorced / Unmarried |

1,957 (20.9) |

|

Household income |

High |

344 (4.5) |

|

Middle–high |

838 (11.0) |

|

Middle |

1,685 (22.1) |

|

Middle–low |

2,869 (37.7) |

|

Low |

1,872 (24.6) |

|

Education |

≤Middle school |

3,560 (38.0) |

|

High school |

3,720 (39.7) |

|

≥College |

2,098 (22.3) |

|

Employment |

Yes |

6,602 (70.3) |

|

No |

2,787 (29.7) |

|

Annual frequency of drinking |

≤1 time/month |

2,212 (37.0) |

|

2–4 times/month |

1,499 (25.1) |

|

≥2 times/week |

2,263 (37.9) |

|

Smoking |

Current smoker |

2,301 (47.8) |

|

Non-smoker or former smoker |

2,512 (52.2) |

|

Body mass index (kg/m2) |

≤24.9 |

2,166 (56.6) |

|

≥25.0 |

1,641 (43.4) |

|

24.1±6.33 |

|

Comorbidities |

Hypertension |

4,909 (52.3) |

|

Perceived health status |

Good |

1,509 (16.1) |

|

Moderate |

4,366 (46.5) |

|

Poor |

3,518 (37.4) |

|

Recognition |

Blood pressure level (yes) |

7,011 (74.6) |

|

Blood sugar level (yes) |

7,163 (76.3) |

|

Diabetes treatment |

Non-drug therapy |

3,497 (37.2) |

|

Drug therapy |

8,663 (92.2) |

|

Insulin injection |

690 (7.3) |

|

Diabetes management education (yes) |

|

2,213 (23.6) |

Table 2.Social Capital, Depression Levels, and Rate of Perceived Stress Among the Participants (N=9,394)

|

Variables |

Categories |

Range |

n (%) or M±SD |

|

Rate of perceived stress |

|

1~10 |

0.26±0.44 |

|

Depression (score) |

|

0~27 |

2.30±3.38 |

|

≤4 |

|

7,856 (83.8) |

|

5~9 |

|

1,118 (11.9) |

|

≥10 |

|

396 (4.2) |

|

Social capital (score) |

|

0~14 |

5.30±1.66 |

|

Trust |

0~2 |

|

|

Neighbor (yes) |

|

6,218 (71.0) |

|

Neighbor-event† (yes) |

|

5,223 (55.6) |

|

Reciprocity |

0~5 |

|

|

Level of safety (yes) |

|

7,849 (83.6) |

|

Natural environment‡ (yes) |

|

7,600 (81.3) |

|

Living environment ‡ (yes) |

|

7,865 (84.0) |

|

Public transport (yes) |

|

6,704 (72.9) |

|

Medical service (yes) |

|

6,753 (72.9) |

|

Social participation |

0~4 |

|

|

Religion (yes) |

|

2,673 (28.5) |

|

Fellowship (yes) |

|

6,106 (65.0) |

|

Leisure (yes) |

|

2,675 (28.5) |

|

Charity (yes) |

|

1,090 (11.6) |

|

Social Network |

0~3 |

|

|

Relative or family (yes) |

|

7,931 (84.5) |

|

Neighbor (yes) |

|

6,772 (72.4) |

|

Friend (yes) |

|

7,612 (81.1) |

Table 3.Mediating Effect of Social Capital on Depression in Middle-Aged Koreans with Diabetes (N=9,394)

|

Causal steps |

B |

SE |

β |

t |

p

|

Adj. R2

|

F |

p

|

|

Step 1. PSS → Social capital†

|

-0.86 |

0.06 |

-.16 |

-14.47 |

<.001 |

.02 |

209.32 |

<.001 |

|

Step 2. PSS → Depression |

2.83 |

0.08 |

.37 |

36.21 |

<.001 |

.13 |

1,311.31 |

<.001 |

|

Step 3. PSS, social capital† → Depression |

|

|

|

|

|

.19 |

998.83 |

<.001 |

|

1) PSS→ Depression |

2.54 |

0.08 |

.33 |

36.21 |

<.001 |

|

|

|

|

2) Social capital† → Depression |

-0.034 |

0.01 |

-.24 |

-24.38 |

<.001 |

|

|

|

|

Sobel Test: B=-0.24, Z=2.65 (p<.05) |

REFERENCES

- 1. GBD 2021 Diabetes Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of diabetes from 1990 to 2021, with projections of prevalence to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet. 2023;402(10397):203-34. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)01301-6

- 2. International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas 2021-10th edition [Internet]. International Diabetes Federation; 2021 [cited 2024 April 15]. Available from: https://diabetesatlas.org/idfawp/resource-files/2021/07/IDF_Atlas_10th_Edition_2021.pdf

- 3. The Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Diabetes Prevalence Trends, 2013-2022. Public Health Weekly Report. 2024;17(43):1860-1. https://doi.org/10.56786/PHWR.2024.17.43.4

- 4. Korean Diabetes Association. Diabetes fact sheet in Korea 2024 [Internet]. Seoul: Korean Diabetes Association; 2024 [cited 2025 January 19] Available from: https://www.diabetes.or.kr/bbs/?code=fact_sheet&mode=view&number=2792&page=1&code=fact_sheet

- 5. American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 5. Facilitating positive health behaviors and well-being to improve health outcomes: standards of care in diabetes-2024. Diabetes Care. 2024;47(Suppl 1):S77-S110. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc24-S005

- 6. Giuntella O, McManus S, Mujcic R, Oswald AJ, Powdthavee N, Tohamy A. The midlife crisis. Economica. 2023;90(357):65-110. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecca.12452

- 7. Sharma K, Akre S, Chakole S, Wanjari MB. Stress-induced diabetes: a review. Cureus. 2022;14(9):e29142. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.29142

- 8. Bădescu SV, Tătaru C, Kobylinska L, Georgescu EL, Zahiu DM, Zăgrean AM, et al. The association between diabetes mellitus and depression. Journal of Medicine and Life. 2016;9(2):120-5.

- 9. Jang SM, Ha HM. The relationship between human capital and depression among middle-aged rural adults: the multiple-parallel mediating effects of social capital. Korean Journal of Health Education and Promotion. 2023;40(1):33-44. https://doi.org/10.14367/kjhep.2023.40.1.33

- 10. Koetsenruijter J, van Eikelenboom N, van Lieshout J, Vassilev I, Lionis C, Todorova E, et al. Social support and self-management capabilities in diabetes patients: an international observational study. Patient Education and Counseling. 2016;99(4):638-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2015.10.029

- 11. Magro-Montañés B, Pabón-Carrasco M, Romero-Castillo R, Ponce-Blandón JA, Jiménez‐Picón N. The relationship between neighborhood social capital and health from a biopsychosocial perspective: a systematic review. Public Health Nursing. 2024;41(4):845-61. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.13323

- 12. Abadi PKA, Ahmadi M, Khalilian A, Ganji J, Sari I. Relationship between social capital, psychological well-being, and quality of life in patients with diabetes mellitus. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2020;30(184):154-60.

- 13. Zhang C, Wu Z, Lopez E, Magboo RG, Hou K. Symptoms of depression, perceived social support, and medical coping modes among middle-aged and elderly patients with type 2 diabetes. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 2023;10:1167721. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2023.1167721

- 14. Xue TM, Rahmaty Z, McConnell E, Xu YL, Corazzini K. Impacts of social capital factors on blood glucose control and depressive symptoms. Innovation in Aging. 2021;5(Suppl 1):626. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igab046.2387

- 15. Sanjari M, Aalaa M, Amini MR, Aghaei Meybodi HR, Qorbani M, Adibi H, et al. Social-capital determinants of the women with diabetes: a population-based study. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders. 2021;20(1):511-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40200-021-00772-9

- 16. Buyukbayram Z, Aksoy M, Gungor A. Investigation of the perceived stress levels and adherence to treatment of individuals with type 2 diabetes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archives of Health Science and Research. 2022;9(1):61-9. https://doi.org/10.5152/ArcHealthSciRes.2022.21088

- 17. Choi HS, Choi JH, Park KH, Joo KJ, Ga H, Ko HJ, et al. Standardization of the Korean version of patient health Questionnaire-9 as a screening instrument for major depressive disorder. Journal of the Korean Academy of Family Medicine. 2007;28:114-9.

- 18. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606-13. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x

- 19. Udedi M, Muula AS, Stewart RC, Pence BW. The validity of the patient health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in patients with type-2 diabetes mellitus in non-communicable diseases clinics in Malawi. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(81):1-7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-019-2062-2

- 20. Putnam RD. Bowling alone: America's declining social capital Culture and Politics. New York: A Reader; 2000. p. 223-34.

- 21. Putnam RD. Bowling alone: America's declining social capital. In: The city reader. 3rd ed. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge; 2015. p. 188-96.

- 22. Jung M, Kim J. Influence of social capital on depression of older adults living in rural area: a cross-sectional study using the 2019 Korea community health survey. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2022;52(2):144-56. https://doi.org/10.4040/jkan.21239

- 23. Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1979;109(2):186-204. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674

- 24. Bai Z, Xu Z, Xu X, Qin X, Hu W, Hu Z. Association between social capital and depression among older people: evidence from Anhui Province, China. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1560. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09657-7

- 25. Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;51(6):1173-82. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173

- 26. Bai S, Wang J, Liu J, Miao Y, Zhang A, Zhang Z. Analysis of depression incidence and influence factors among middle-aged and elderly diabetic patients in China: based on CHARLS data. BMC Psychiatry. 2024;24:146. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05473-6

- 27. National Center for Mental Health. National Mental Health Status Report 2019 [Internet]. Seoul: National Center for Mental Health; 2020 [cited 2024 April 14]. Available from: https://www.ncmh.go.kr/research/board/boardView.do?no=3411&bn=SNMH_COMMON_BOARD&menu_cd=03_02_00_01

- 28. Messina R, Lenzi J, Rosa S, Fantini MP, Di Bartolo P. Clinical health psychology perspectives in diabetes care: a retrospective cohort study examining the role of depression in adherence to visits and examinations in type 2 diabetes management. Healthcare. 2024;12(19):1942. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12191942

- 29. Novak M, Bjorck L, Giang KW, Heden-Stahl C, Wilhelmsen L, Rosengren A. Perceived stress and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a 35-year follow-up study of middle-aged Swedish men. Diabetic medicine. 2013;30(1):e8-16. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.12037

- 30. Kim CJ. Mental health and self-care activities according to perceived stress level in type 2 diabetic patients with metabolic syndrome. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing. 2010;22:51-9.

- 31. Wang L, Li J, Dang Y, Ma H, Niu Y. Relationship between social capital and depressive symptoms among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients in northwest China: a mediating role of sleep quality. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021;12:725197. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.725197

- 32. Ekou FK, Eze IC, Aka J, Kwiatkowski M, Merten S, Acka FK, et al. Randomised controlled trial on the effect of social support on disease control, mental health and health-related quality of life in people with diabetes from Cote d'Ivoire: the SoDDiCo study protocol. BMJ Open. 2024;14(1):e069934. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-069934

- 33. Ma X, Bai W, Yu F, Yang F, Yin J, Shi H, et al. The effect of neighborhood social cohesion on life satisfaction in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients: the chain mediating role of depressive symptoms and sleep quality. Frontiers in Public Health. 2023;11:1257268. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1257268

- 34. Hill-Briggs F, Adler NE, Berkowitz SA, Chin MH, Gary-Webb TL, Navas-Acien A, et al. Social determinants of health and diabetes: a scientific review. Diabetes Care. 2020;44(1):258-79. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci20-0053

- 35. Han SH. Social capital and perceived stress: the role of social context. Journal of affective disorders. 2019;250:186-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.03.034